Emergency Department Visits for Depression in the United States

Abstract

The authors used data from the 1997-2000 National Hospital Ambulatory Care Surveys to quantify and characterize visits to emergency departments for depression. Each year there were 580,000 visits associated with a primary diagnosis of depression. More than half of these visits resulted in admission to a hospital or another facility. Twelve percent of visits involved a self-inflicted injury. Antidepressants were offered during 18 percent of visits. Mental status examinations were given during 52 percent of visits. Overall, 81 percent of visits were by patients who had health insurance coverage.

It is generally assumed that depression care takes place in the primary care or specialty mental health setting. However, for persons who do not have resources to obtain other sources of care, emergency departments may be used for nonemergent depression care. There is little in the scientific literature that provides national estimates of the number of visits to emergency departments for depression or examines the content of care during those visits. The study reported here assessed the frequency of visits to emergency departments for depression in the United States, patient characteristics associated with those visits, and the content of care.

Methods

We analyzed visits to emergency departments by using data from the 1997-2000 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NHAMCS). The NHAMCS, conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), is a nationally representative sample of visits to emergency departments (N=93,109) in noninstitutional, general, short-stay, nonfederal hospitals in the United States; the health care provider is the respondent (1).

The analysis was limited to visits associated with a primary diagnosis of depression on the basis of diagnoses assigned by providers during the visit (ICD-9 codes 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311, and 298.0). The 1997-2000 NHAMCS sample comprises 775 visits to emergency departments associated with a primary diagnosis of depression.

Antidepressant drug visits were defined as visits at which at least one antidepressant was prescribed, supplied, administered, ordered, or continued. Rates of mental status examinations (MSEs) during visits were assessed on the basis of responses to a check box on the patient record form indicating that a MSE was conducted. Visit disposition was assessed with the following categories: referred to another physician, referred to social services, admitted to the hospital, transferred to another facility, instructed to return to the emergency department if needed, and no follow-up. These disposition categories were not mutually exclusive, except for no follow-up. Visits were classified by patients' age, race, ethnicity, gender, region, and insurance type.

The NCHS included weights in the NHAMCS so that the sample would represent all visits to emergency departments in the United States, and all estimates presented here are based on these weights. To account for the sampling strategy, the survey procedures in Stata were used to calculate the estimates (2).

Results

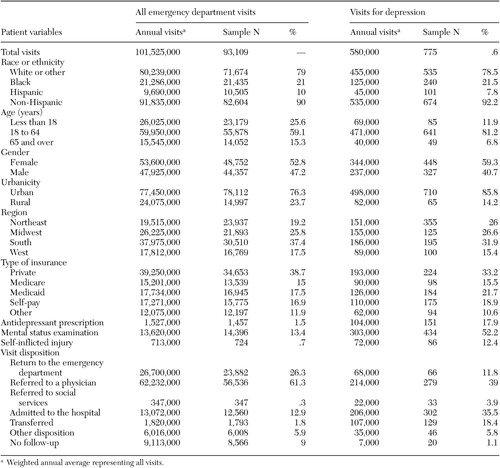

The national weighted estimated annual number of visits to emergency departments for all reasons and for depression are presented in Table 1. A total of 580,000 emergency department visits for depression occurred annually between 1997 and 2000, representing .6 percent of all visits. A majority of these visits were made by nonelderly adults, females, and persons living in urban areas. Approximately 19 percent of these visits were by persons who had no health insurance or chose not to file a health insurance claim; this rate is similar to the rate for all emergency department visits (17 percent) and the uninsured rate in the general population (17 percent) (3).

The characteristics of emergency department visits for depression are summarized in Table 1. Antidepressant medications were offered at 18 percent of visits. Nearly 43 percent of visits resulted in a referral to a physician or to social services. More than half of all visits resulted in an admission to the hospital or transfer to another facility. Overall, 91 percent of visits resulted in a referral to another provider, hospital admission, or transfer to another facility. Patients did not receive an antidepressant medication or a referral, transfer, or hospital admission during 6 percent of visits; 3 percent received an antidepressant medication but were not admitted, transferred, or referred.

Twelve percent of emergency department visits for depression involved a self-inflicted injury. An MSE was reported by the clinician for approximately half of all emergency department visits for depression, for 44 percent of visits at which an antidepressant was prescribed, and for 71 percent of visits involving a self-inflicted injury. Patients were admitted to the hospital or transferred to another facility in the case of 35 percent of visits involving a self-inflicted injury during which no MSE was conducted.

Discussion and conclusions

The high prevalence of self-inflicted injuries and the high rate of hospital admissions and transfers observed in this study suggest that many emergency department visits for depression may be for emergent depression care. We theorized that patients who did not have resources to obtain other forms of care would use emergency departments as a primary source of depression care. Although it was not possible to ascertain whether individuals were using the emergency department for this reason, the vast majority of emergency department visits for depression were by persons who had some form of health insurance.

Perhaps the most surprising finding is the low rate of MSEs. Appropriate care requires an MSE whenever depression is diagnosed, or even suspected, in an emergency setting. This is especially true in the case of suicidal or parasuicidal behavior or when an antidepressant is prescribed. Yet we found that MSEs were not conducted during many of these visits. Furthermore, it does not appear that the low rate of MSEs was attributable to the patient's being admitted or transferred, in which case it might be assumed that an MSE will be conducted later. One possibility is that providers underreported MSEs—although the provider completing the patient record form merely had to check a box indicating that this examination was performed. Specially trained interviewers visit the hospitals before the survey to explain survey procedures and to explain how to fill out the patient record form.

The low rate of prescribing of antidepressants is not surprising. It takes between two and four weeks for antidepressants to begin relieving the symptoms of depression, so these medications will not provide any short-term relief for persons with acute symptoms of depression. For individuals who are not in imminent danger, referrals to mental health specialists would be appropriate, whereas for those who are in imminent danger, admission to the hospital or transfer to a psychiatric facility would be the best course of action. We found that the most common disposition for depressed patients was referral to an outside provider. Studies have shown that compliance with these referrals is only poor to fair (4,5,6).

The study's findings should be interpreted cautiously because of limitations of the data. It is likely that a diagnosis of depression was not recorded on the patient record form, even though the patient had depression during many visits. Also, there is no assurance that the diagnostic criteria for depression were met, even though a diagnosis of depression was recorded.

Even given these limitations, this study represents the first attempt to quantify the burden of depression in U.S. emergency departments and has provided a description of the characteristics of those visits. It appears that physicians in emergency departments are providing referrals to other providers for persons seeking depression care and admitting to the hospital or transferring to other facilities persons with depressive symptoms that are acute enough to put the patient in imminent danger. Further research is necessary to properly assess the adequacy of care provided to persons presenting in emergency departments with depressive symptoms.

Dr. Harman is affiliated with the department of health services research, management, and policy of the College of Public Health and Health Professions at the University of Florida, P.O. Box 100195, Gainesville, Florida 32611-0195 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Scholle is with the National Committee for Quality Assurance in Washington, D.C. Dr. Edlund is with the department of psychiatry of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System in Little Rock.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of emergency department visits for depression, 1997 to 2000

1. McCaig LF, Ly N: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey:2000 Emergency Department Summary: Data From Vital and Health Statistics. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 2002Google Scholar

2. StataCorp: Stata Statistical Software: Release 7.0 Special Edition. College Station, Tex, Stata Corporation, 2002Google Scholar

3. Hoffman C, Wang M: Health Insurance Coverage in America:2002 Data Update. Washington, DC, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2003Google Scholar

4. Solomon P, Gordon B: Follow-up of outpatient referrals from a psychiatric emergency room. Social Work in Health Care 13:57–67, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Krulee D, Hales R: Compliance with psychiatric referrals from a general hospital psychiatry outpatient clinic. General Hospital Psychiatry 10:339–345, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Blouin A, Perez E, Minoletti A: Compliance to referrals from the psychiatric emergency room. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 30:103–106, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar