Use of Mental Health Services Among Older Youths in Foster Care

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined lifetime, 12-month, and current mental health service use among older youths in the foster care system and examined variations in mental health care by race, gender, maltreatment history, living situation, and geographic region. METHOD: The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents, the Child Trauma Questionnaire, and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule were used in interviews with 406 youths in Missouri's foster care system who were aged 17 years. RESULTS: Ninety-four percent of the youths had used a mental health service in their lifetime, 83 percent used a mental health service in the past year, and 66 percent were currently receiving a mental health service. Lifetime rates for inpatient psychiatric care (42 percent) and other residential programs (77 percent) were exceptionally high. A quarter of the youths received mental health services before they entered the foster care system. Among youths who received residential services, half did not receive community-based services before receiving residential services. After the analyses controlled for need, predisposing characteristics, and enabling characteristics, youths of color were less likely to receive outpatient therapy, psychotherapeutic medications, and inpatient services, and they were more likely to receive residential services. Youths who had been neglected and youths in kinship care were less likely to receive some types of services. Geographic differences in service use were common and sometimes mediated the effect of race on service use. CONCLUSIONS: The child welfare system was actively engaged in arranging mental health services for youths in the foster care system, but the system was unable to maintain many youths in less restrictive living situations. The variations by race and geography indirectly indicate quality concerns.

Studies, using a variety of methods, have determined that children and adolescents in the foster care system use mental health services at exceptionally high rates (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12). Yet little is known about the specific types of services used, the timing of these services, and which youths are more likely to use mental health services. This knowledge gap is particularly significant for the 100,000 youths in the U.S. foster care system who are older than 16 years (13) because they typically lose Medicaid eligibility when they leave the foster care system and tend to have poor early-adult outcomes (14,15,16).

Data on types of services that are used across the continuum of care can inform policy makers about the degree to which youths are served in less restrictive settings. Service timing data can address whether the foster care system is asked to care for youths who came to the system with previous service histories, whether youths receive community services before they receive more restrictive mental health services, and whether the foster care system is responding in a timely manner to psychiatric problems.

Determining who uses services can help uncover service disparities and system priorities. The question of who receives services is often viewed as an interplay of predisposing factors that describe the propensity to use services (including demographic variables and attitudes toward services), enabling factors that describe the means that people have to obtain services (including insurance and geography), and the need for services (17).

Findings were mixed from earlier studies that examined demographic differences in service use among youths in foster care. Two studies found females to be heavier service users than males (18,19), whereas three studies reported the opposite (1,4,6) and one found no difference (11). In San Diego County white youths were more likely than African-American and Hispanic youths to receive mental health services (4,19). In Los Angeles County, among children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, whites were five times as likely to use mental health services as Hispanics; no significant difference was found between whites and African Americans (10). These disparities persisted after controlling for problem severity or level of functioning, type of maltreatment, age, and gender (4,10).

Youths' living situations may also influence service use. Two California studies documented that children in kinship care received fewer mental health services than other youths in the foster care system (4,9).

Furthermore, previous studies found that indicators of need were related to service use. Sexually abused youths were nearly five times as likely as other children in the foster care system to receive mental health services (11,20). Youths who were in placement because of physical abuse were 2.43 times as likely as other youths to use services (11). Psychiatric diagnosis (10,21) and problem severity (11,19,20) have routinely been related to service use among youths in foster care.

Our study addressed five research questions with a sample of 406 youths in Missouri's foster care system who were aged 17 years. What proportion of youths used the different kinds of mental health services? Did use of mental health services begin before the youths entered the foster care system? For youths with mental health problems at the time of entrance into the foster care system, how long did it take to receive mental health services? Did youths receive outpatient services before receiving residential services? Who used the different types of services? We hypothesized that sexually abused youths, white youths, and youths in non-kin family foster care would be more likely to use services.

Methods

Participants

From December 2001 to May 2003 the Missouri Children's Division provided to the researchers the names of youths who were in its custody and who would be turning 17 the following month and the names of their caseworkers. The youths were from eight counties, which were from four of the seven administrative regions of the Missouri Children's Division and included the St. Louis metro area, surrounding counties, and counties in Southwest Missouri. After the Washington University institutional review board approved the study's procedures, caseworkers from the Missouri Children's Division screened potential participants for exclusion criteria and provided informed consent. Exclusion criteria included an IQ score below 70, placement over 100 miles from any of the eight counties, and continual runaway status through 45 days after the youth's 17th birthday.

Of the 450 youths who were eligible for our study, 406 (90 percent) were interviewed. Of those eligible, 39 (9 percent) chose not to participate. We were unable to contact the case manager for four youths, and we were unable to complete one interview for which consent and assent were obtained.

Procedures

Youths were interviewed in person at their residences by trained professional interviewers and were paid $40 for their participation.

Dependent variables. Service use was assessed with the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA) (22,23). With children older than ten years, the SACA has demonstrated good to excellent test-retest reliability for lifetime and past-year service use (22) and favorable correspondence between youth and parent report (23). We chose six dependent variables for multivariate analyses on the basis of their prevalence and importance: lifetime inpatient psychiatric service use, lifetime outpatient mental health service use (outpatient therapy, day treatment, and mental health care provided by a primary care physician), lifetime residential mental health service use (group home or residential treatment), current outpatient mental health service use, current residential mental health service use, and current psychotropic medication use. The SACA obtains medication information from pill bottle labels. When pill bottles were not available, interviewers asked caregivers for medication information.

Predisposing variables. Race was self-reported. Missouri has small numbers of Asians, American Indians, and Hispanics. For the analyses, we combined youths from these categories with youths from African American and multiracial categories to create a category called youths of color. To assess attitudes toward service, we amended the confidence subscale of the Attitude Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help (24) by updating terms, dropping an out-of-date item, and adding one item on medications ("I think medications for emotional or behavioral problems can be helpful for many people"). Internal consistency reliability was .74 for this sample. We used the mean item score with a range from 0, strongly disagree, to 4, strongly agree.

Living situation was coded by the interviewer and grouped into five categories: with a parent, kinship care, non-kin family foster care, congregate care, and semi-independent living.

Enabling variables. Youths reported the age at which they first came into the foster care system. Youths who had been in the system for longer may have had more opportunity to receive services. Geographic regions were used in some analyses.

Need variables. Physical abuse and physical neglect histories were assessed with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (25). The recommended cutoff scores were used to indicate moderate or severe maltreatment. Respondents were considered to be sexually abused if they answered yes to any of the three interview items that were adapted from Russell (26) and were used in a previous study of older youths in foster care (27). Lifetime psychiatric disorder and past-year psychiatric disorder were measured with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (28), which assessed for posttraumatic stress disorder, major depression, mania, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional disorder, and conduct disorder.

Analyses

Hierarchical logistic regression was used to assess the relationships between independent variables and service use. Predisposing variables were entered first, followed by enabling and need variables. We monitored drops in odds ratios (ORs) for possible mediating effects. For current mental health service use we also entered the dummy codes for living situation. For analyses with two dependent variables—current outpatient therapy and current medication use—we entered the attitudes toward services scale in the first step. In a second step, we entered multiplicative terms to test for numerous interactions.

Because racial disparities in service use were robust and the percentage of youths of color ranged from 14 percent in Southwest Missouri to 90 percent in St. Louis City, we conducted post hoc analyses to explore geographic differences in racial disparities. First, we entered dummy codes for region into the regression equations described above (with the region surrounding the St. Louis metropolitan area as the comparison category). When results indicated that one region had higher or lower rates of service than other regions, we examined racial disparities within and outside these regions. For all analyses, a significance level of .05 (two-tailed) was set.

Results

Sample

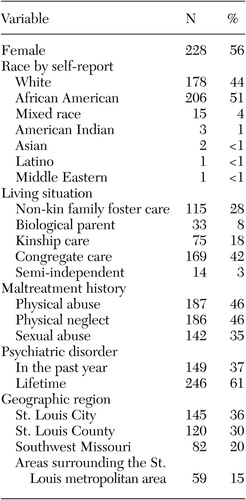

The mean±SD age at interview was 16.99±.09 years. The youths entered the foster care system at a mean age of 10.86±2.26 years. Further characteristics of the sample are described in Table 1.

Rates of service use

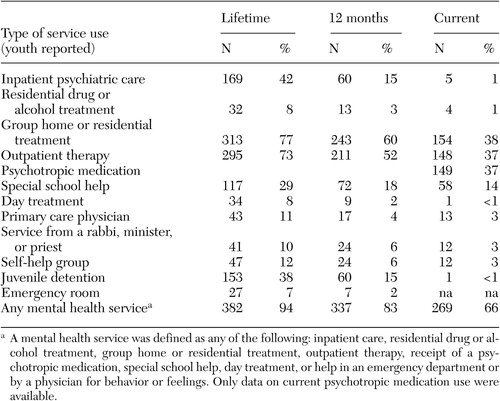

Lifetime, 12-month, and current service use rates for several types of services are reported in Table 2. The youths reported high rates of inpatient psychiatric care, residential services, and outpatient therapy. Of the 149 youths who had a psychiatric disorder within the past year, 136 (91 percent) received a mental health service in the past year and 120 (81 percent) were currently receiving a mental health service. Out of the total sample of 406 youths, 106 (26 percent) received an antidepressant medication, 77 (19 percent) received a medication classified as having antipsychotic properties, 71 (18 percent) received a medication with antimanic properties, 34 (8 percent) received a central nervous system stimulant, and 28 (7 percent) received an antianxiety medication.

First use of services

Of the 382 youths who had used a mental health service in their lifetime, 96 (25 percent) reported that their first use of a mental health service occurred before the year that they first entered the foster care system.

Access to services

Each of the 110 youths who reported a psychiatric disorder that began before or during the year of their foster care entrance and who had no mental health service use before entering foster care received a mental health service after entering the foster care system; 80 percent of these youths (N=88) received a mental health service within a year of entering the foster care system.

Community-based and residential services

Of the 313 youths who had received group home or residential treatment services, 79 (25 percent) reported that they had never received a community-based outpatient mental health service. Another 78 youths (25 percent) reported that they received their first residential service before the year that they received their first community-based outpatient service.

Predictors of service use

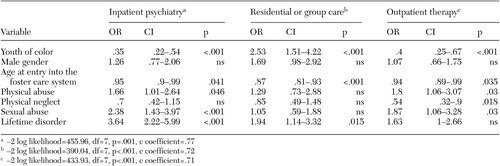

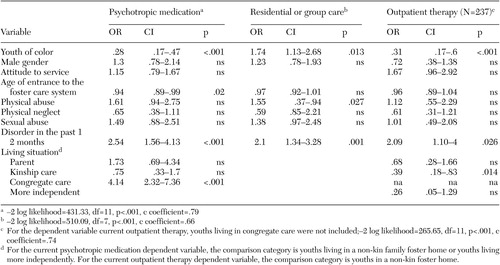

Predictors of selected lifetime and current mental health service use variables are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Race was associated with each dependent variable. Youths of color were less likely to receive lifetime inpatient services, lifetime and current outpatient therapy, and current medication, and they were more likely to receive lifetime and current residential services. Gender was not related to service use. Presence of a psychiatric disorder was associated with increased odds of each kind of service use except for lifetime outpatient therapy, whereas maltreatment history, living situation, and age at entry into the system were associated with some services, but not others. No evidence of mediating or interaction effects was found.

Geography and racial disparities

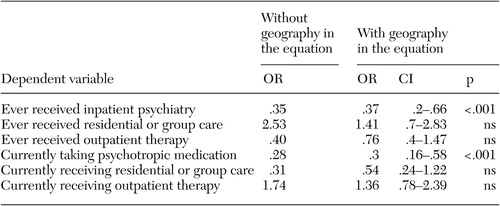

The decreases in ORs for race when geographic region was entered into the equations are shown in Table 5. With four dependent variables, geographic region mediated the effect of race on service use, with the effect roughly halved. With three of these four dependent variables, a single region differed from the comparison region in service use.

Youths from St. Louis County were more likely than those from the comparison region to receive residential services in their lifetimes. Within St. Louis County, youths of color were no more likely than white youths to have been in residential service. Outside this region, youths of color were more likely to have been in residential service (OR=2.82, CI=1.55 to 5.14, p<.001).

Youths in St. Louis City were less likely than youths in the comparison region to have received outpatient therapy in their lifetime. Within St. Louis City, being a youth of color was not associated with outpatient service use. However, in the other regions, being a youth of color was associated with outpatient service use, although the results were not statistically significant; the OR (.54) was similar to that for the full sample, but with reduced statistical power.

Youths from Southwest Missouri were more likely than youths in the comparison region to currently be receiving outpatient therapy. Within this region, 80 percent of youths of color who were not in residential care were receiving outpatient therapy. In the other regions, youths of color were less likely to receive outpatient therapy than white youths (OR=.36, CI=.17 to .76, p=.007).

Discussion and conclusions

Results from this study suggest that foster care case managers are actively engaged in arranging mental health services for older youths in the foster care system. Few youths with psychiatric problems were not receiving services, and youths who entered the system with psychiatric problems tended to receive mental health services soon after entering the system.

However, the youths received alarmingly high rates of the most invasive and stigmatizing mental health services—inpatient and residential programs—and 50 percent of these youths did not receive a community-based service before receiving a more invasive service. Reasons for these high use rates might include the difficulty of finding family living arrangements for youths in emotional crisis, too few intensive services designed to keep troubled youths in family foster homes (such as treatment foster care), and traditional reasons for such placements, such as protection of the child, protection of the community, and the need for treatments not available in a community setting (29). The large percentage of youths in residential programs who are aged 17 years means that many youths will make the transition to more independent living situations from highly structured programs.

The large percentage of youths who were taking psychotherapeutic medications leads to two questions. Who will pay for these medications after the youths leave the foster care system? And what will happen to youths who are asked to make the transition to the community without the support of continued medication therapy? Most youths lose the automatic Medicaid eligibility that goes with involvement in the foster care system when they are discharged from foster care. Even though federal law allows states to expand Medicaid coverage to age 21 years for youths who were in the custody of the child welfare authority on their 18th birthdays (30), few states use this option (31).

Our study uncovered substantial racial disparities in service use. Racial disparities in the use of mental health services and in the use of the child welfare system are common (32,33). Possible reasons for the disparities include access, societal conditions, differential detection of problems, and judicial and professional bias. Because youths in the foster care system share common enabling characteristics for gaining access to services—uniform Medicaid eligibility, supervised caregiving, and case managers—the racial disparities seen here are potentially more reflective of bias than is typical. Some adults may view emotional and behavioral problems in mental health terms for white youths but not for youths of color, whereas the behaviors of youths of color may be seen as purposefully problematic, resulting in removal from the community. The large numbers of youths who received residential services may also reflect a shortage of foster families who are willing to take older African-American youths.

Although geographic region mediated the effect of race on service use for some dependent variables, further analyses revealed that racial disparities were not accounted for by geographic differences. Instead, it appears that racial disparities existed in the absence of a strong geographic influence on service use. For example, in a region where lifetime residential service use was the norm, no racial disparity was found: almost all youths in the foster care system went into residential care at some point. In other regions, there was a racial difference in service use.

These findings add to the small but growing body of literature about geographic differences in the use of mental health services (34,35,36,37). Geographic differences in service use are not well understood and deserve more study. We asked caseworkers in the study areas about the availability of mental health services in their regions when we presented our results to them; none of them reported any shortage of any of the services that we studied. Issues of organizational culture may explain some differences. Social service offices may establish unofficial norms that differ across regions as to which behaviors or symptoms warrant referral for different treatment services. In the foster care system, judicial preferences may also play a role. No matter their source, racial and geographic variations indicate quality problems. The color of a youth's skin or the region within a state where the youth is from should not be a main determinant of whether the youth receives services.

This study provides further evidence that the more overt forms of child maltreatment lead to greater involvement in services even when controlling for disorder, although the ORs for receiving mental health services when the youth had been sexually abused were half or less those reported elsewhere (11,20). Youths who lived in kinship care were less likely than youths in non-kin foster families to receive outpatient therapy when the analyses controlled for other factors. There are several explanations for this disparity: youths in kinship care typically receive less frequent case manager visits (38), which can lead to less recognition of problems; kinship caregivers may have less knowledge of available services (39,40,41); kinship caregivers may have differing views about the appropriateness of mental health services; and case managers may believe that children who are not separated from their family members are less in need of mental health services.

One limitation of the study is that youths who are aged 17 years in the foster care system are not representative of youths in the system in general. Youths who remain in the system until age 17 may have greater needs for mental health services than other youths in the system.

Additional limitations of our study include the focus on only one state's system, a reliance on self-reported data, and an inability to capture the full range, duration, and severity of stressors and specific conditions as well as the context that together constitute a need for mental health services. Even though we used service history information to make rough generalizations about how youths with mental disorders are treated in the foster care system, this approach is no substitute for an evaluation of the quality of the mental health services that youths in the foster care system receive more directly. We know that youths in care receive mental health services. We do not know whether they receive services that work, that meet their needs, that are evidence based, or that are acceptable to them.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by grant R01-MH-61404 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the department of social work at Washington University, Campus Box 1196, Saint Louis, Missouri 63130 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Spitznagel is also with the department of mathematics at Washington University in Saint Louis. Dr. Zima is also with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles.

|

Table 1. Sample characteristics of 17-year-old youths in custody of the Missouri Children's Division (N=406)

|

Table 2. Lifetime, 12-month, and current service use reported by 17-year-old youths in custody of the Missouri Children's Division (N=406)

|

Table 3. Predictors of lifetime mental health service use among 17-year-old youths in custody of the Missouri Children's Division (N=406)

|

Table 4. Predictors of current mental health service use among 17-year-old youths in custody of the Missouri Children's Division (N=406)

|

Table 5. Post hoc analyses of geography and racial disparities in service use among 17-year-old youths of color in custody of the Missouri Children's Division (N=406)

1. Blumberg E, Landsverk J, Ellis-MacLeod E, et al: Use of the public mental health system by children in foster care: client characteristics and service use patterns. Journal of Mental Health Administration 23:389–405, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Halfon N, Berkowitz G, Klee L: Mental health service utilization by children in foster care in California. Pediatrics 89:1238–1244, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

3. DosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, et al: Mental health services for youths in foster care and disabled youths. American Journal of Public Health 91:1094–1099, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Leslie LK, Landsverk J, Ezzet-Lopstrom R, et al: Children in foster care: factors influencing outpatient mental health service use. Child Abuse and Neglect 24:465–476, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Takayama JI, Bergman AB, Connell FA: Children in foster care in the state of Washington, JAMA 271:1850–1855, 1994Google Scholar

6. Early TJ, Mooney DD: Mental health service use for children in foster care in Illinois. Urbana, Ill, Children and Family Research Center, School of Social Work, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2002Google Scholar

7. Harman JS, Childs GE, Kelleher KJ: Mental health care utilization and expenditures by youth in foster care. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 154:1114–1117, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. McMillen JC, Tucker J: The exit status of older adolescents at exit from out-of-home care. Child Welfare 78:339–360, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

9. Berrick JD, Barth RP, Needell B: A comparison of kinship foster homes and foster family homes: implication for kinship foster care as family preservation. Children and Youth Services Review 16:33–63, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Zima BT, Bussing R, Yang X, et al: Help-seeking steps and service use among children in foster care. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 27:271–285, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Garland AF, Landsverk JL, Hough RL, et al: Type of maltreatment as a predictor of mental health service use for children in foster care. Child Abuse and Neglect 20:675–688, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Courtney M, Terau S, Bost M: Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Conditions of Youth Preparing to Leave State Custody. Chicago, Chapin Hall Center for Children, 2004Google Scholar

13. Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System Report: Preliminary FY 2001 Estimates as of March 2003, report no 8. US Department of Health and Human Services, 2003. Available at www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/publications/afcars/report8.pdfGoogle Scholar

14. Courtney ME, Piliavin I, Grogan-Kaylor A, et al: Foster youth transitions to adulthood: a longitudinal view of youth leaving care. Child Welfare 80:685–717, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

15. Goerge RM, Bilaver L, Lee BJ, et al: Employment Outcomes for Youth Aging out of Foster Care. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2002Google Scholar

16. A National Evaluation of Title IV-E Foster Care Independent Living Programs for Youth: Phase 2, Final Report. Washington, DC, Westat Inc, 1991Google Scholar

17. Anderson RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

18. Garland A, Aarons GA, Brown SA, et al: Diagnostic profiles associated with utilization of mental health and substance abuse services among high risk youth. Psychiatric Services 54:562–564, 2003Link, Google Scholar

19. Garland AF, Landsverk JA, Lau AS: Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use among children in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review 25:491–507, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Leslie LK, Hurlburt MS, Landsverk J, et al: Mental Health Services for Children in Foster Care: A National Perspective: Beyond the Clinic Walls. Abstract from the National Institute of Mental Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse Services Conference, Washington, DC, Mar 11–12, 2003Google Scholar

21. Garland AD, Aarons GA, Brown SA, et al: Diagnostic profiles associated with utilization of mental health and substance abuse services among high risk youth. Psychiatric Services 54:562–564, 2003Link, Google Scholar

22. Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, Stiffman AR, et al: Reliability of the services assessment for children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services 52:1088–1094, 2001Link, Google Scholar

23. Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, et al: The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): adult and child reports. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:1032–1039, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Fischer EH, Turner JL: Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 35:79–90, 1970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Bernstein DP, Fink L: The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Manual. San Antonio, Psychological Corporation, 1998Google Scholar

26. Russell DEH: The Secret Trauma: Incest in the Lives of Girls and Women. New York, Basic Books, 1986Google Scholar

27. Auslander WF, McMillen JC, Elze D, et al: Mental health problems and sexual abuse among adolescents in foster care: relationship to HIV risk behaviors and intentions. AIDS and Behavior 6:351–359, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Robins L, Cottler L, Bucholz K, et al: Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. St. Louis, Mo, Washington University in St Louis, 1995Google Scholar

29. Barker P: The future of residential treatment for children, in Children in Residential Care: Critical Issues in Treatment. Edited by Shaefor CE, Swanson AJ. New York, van Norstrand Reinhold, 1988Google Scholar

30. Foster Care Independence Act of 1999, PL 106–169Google Scholar

31. National Resource Center for Youth Services: State by State Fact Page. National Resource Center for Youth Development, and the National Foster Care Coalition. Available at www.nrcys.ou.edu/NRCYD/state_home.htmGoogle Scholar

32. Mental health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2001Google Scholar

33. Roberts DE: Racial Disproportionality in the US Child Welfare System: Documentation, Research on Causes, and Promising Practices: Working Paper No 4. Baltimore, Md, Annie E Casey Foundation, 2002Google Scholar

34. Kelly A, Jones W: Small area variation in the utilization of mental health services: implications for health planning and allocation of resources. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 409:527–532, 1995Google Scholar

35. Semke J, Perdue S: Regional patterns of service for individuals with severe mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 25:541–547, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Hendryz MS, Urdaneta ME, Borders T: The relationship between supply and hospitalization rates for mental illness and substance use disorders. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:167–176, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Hendryx MS, Rohland BM: A small area analysis of psychiatric hospitalizations to general hospitals: effects of community mental health centers. General Hospital Psychiatry 16:313–318, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Gebel TJ: Kinship care and non-relative family foster care: a comparison of caregiver attributes and attitudes. Child Welfare 75:5–18, 1996Google Scholar

39. Chipman R, Wells SJ, Johnson MA: The meaning of quality on kinship foster care: caregiver, child, and worker perspective. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services 83:508–520, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Geen R: Foster children placed with relatives often receive less government help. Washington, DC, Urban Institute, series no A, A-59, 2003Google Scholar

41. Wells SJ, Agathen JM: Evaluating the Quality of Kinship Foster Care: Final Report. Urbana, Ill, Children and Family Research Center, School of Social Work, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1999Google Scholar