Clinicians' Adherence to an Algorithm for Pharmacotherapy of Depression in the Texas Public Mental Health Sector

Abstract

This study evaluated clinicians' adherence to the major depressive disorder algorithm of the Texas Implementation of Medication Algorithms (TIMA) as a component of usual care in the Texas public mental health system. Data were collected from two Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation centers between April and December 2000. Clinician adherence measures included documentation of outcome measures, prescribing patterns (correct medications, therapeutic dosing, dosage increases, and appropriate medication changes), and visit frequency. Clinicians had consistently high adherence to appropriate drug regimens, at appropriate dosages. Variability in attempts to increase dosages when warranted, visit frequency, and documentation of patient outcome measures between clinicians were seen. The results suggest that implementation of medication algorithms is possible in the public mental health sector.

The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) was a study that evaluated the clinical and economic outcomes of an algorithm-driven disease management program for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder in the public mental health sector (1). After this research, the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation implemented the TMAP algorithms, subsequent to a legislative mandate, as a component of routine care through the Texas Implementation of Medication Algorithms (TIMA) (2). The aim of the study reported here was to evaluate the implementation of the TIMA algorithm for major depressive disorder by assessing clinicians' adherence to the algorithm's recommendations. The clinics studied were not involved in TMAP.

Methods

The clinician sample for this study comprised eight staff psychiatrists and one nurse practitioner from two Texas community mental health centers. Clinicians participated in a one-day training session on the major depressive disorder algorithm. Training involved a discussion of the reasons and rationale for guidelines or algorithms, pharmacologic treatment options for depression, use of brief rating scales, and a step-by-step explanation of how to use the clinical record form (CRF) for uniform chart documentation. This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board for the protection of human research subjects at the University of Texas at Austin. The institutional review board deemed that patient consent was not necessary.

The study sample comprised 117 patients who were treated for depression in these two centers. To be included in the study, patients had to be between the ages of 18 and 64 years and have a primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder with or without psychotic features, as diagnosed by their physician. Patients who required a medication change or who were started on a new antidepressant were eligible for inclusion. Patients' medication management was provided by the clinicians, whose findings were documented on the CRF.

Each center generated a list of patients who had a current diagnosis of depression, with or without psychotic features. Each patient's chart was examined for eligibility criteria. For patients who met the study criteria, data were collected for an eight-month period (April to December 2000) and included primary diagnosis, demographic characteristics, patient visit dates, all psychotropic medications prescribed and dosages, scores on the Quick Inventory for Depressive Symptoms-Self Rated (QIDS-SR) (3), 0- to 10-point clinician assessments of symptoms and severity of side effects, and a Clinical Global Impression (CGI).

Clinicians' adherence to the algorithm was assessed by using CRF documentation. For each stage of the algorithm at which a patient was entered, a "report card" score was generated for the treating clinician. If more than one provider saw the patient during the study, the patient was classified as having multiple providers.

For each patient, the clinician report card contained a maximum of five adherence measures: appropriate drug regimen, therapeutic antidepressant dosages, appropriate dosage increases, adequate medication trials, and adequate provider contact. Clinicians scored a 1 if they adhered to a report card item and a 0 if they did not. A score of "not applicable" was used if an individual item was not appropriate for scoring.

Adherence was calculated by adding the total points scored, dividing by the total possible points for each patient, and multiplying this number by 100. This method determined the clinician's percentage adherence to the algorithm for each patient at every stage of the algorithm at which treatment was received. The clinicians' overall percentage adherence scores were determined by summing the points scored for all items, dividing by the total number of possible points, and multiplying this number by 100.

To weight each clinician equally, the total adherence score for each report card item was calculated by taking an average of the percentage adherence score. In addition, to give each item equal weight, overall percentage adherence for each clinician was calculated by taking an average of the percentage adherence score for each item.

Appropriate antidepressant medication was defined as an antidepressant medication regimen that is recommended in one of the stages of the TIMA depression algorithms. An example is use of a selective serotonin specific reuptake inhibitor (such as fluoxetine), nefazodone, mirtazapine, venlafaxine XR, or bupropion SR monotherapy at stage 1, 2, or 3 of the algorithm for nonpsychotic depression (4).

Antidepressant medication dosage was defined as achievement of a minimum therapeutic antidepressant dosage by week 1 to 3 (5).

Appropriate dosage increase was defined as follows. If a patient's depressive symptoms did not improve adequately (below 50 percent improvement) by week 6, the antidepressant dosage should be increased, provided the patient was not experiencing side effects. If a patient did not remain in care for at least six weeks, this item was not scored.

An adequate medication trial was defined as maintaining a patient on at least a minimum therapeutic dosage for a minimum of six weeks unless the patient experienced severe side effects. In addition, a patient's medication regimen should be changed within 16 weeks if the patient had not achieved at least moderate improvement in symptoms (below 50 percent response) by initiating either a new antidepressant monotherapy, an augmenting agent (for example, lithium) in conjunction with the antidepressant, or combination therapy (two antidepressant medications at therapeutic dosages). This report card item was designed to assess whether clinicians were changing medications too rapidly or continuing a regimen in the face of persistent depressive symptoms.

In terms of adequate provider contact, guidelines from the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) (6) recommend that patients have at least three follow-up visits after an initial visit, within a 12-week period. Because clinicians' caseloads at the two centers limit appointment availability, adequate provider contact was defined as three follow-up visits within a 16-week period. This item was not scored if the patient did not remain in care for 16 weeks.

Results

Over an eight-month period, 117 patients were seen for a total of 396 visits—39 men and 78 women. Nine patients (8 percent) were African American, 26 (22 percent) were Hispanic, and 82 (70 percent) were Caucasian. Nineteen patients (16 percent) had a single depressive episode, whereas 92 (79 percent) had a diagnosis of recurrent depression. Six patients (5 percent) had a diagnosis of depression with psychotic features. The average age of the patients was 36.6±10.7 years.

Patients were seen for an average of 3.4±1.98 visits (range, 1 to 10). Fifty of the 117 patients (43 percent) remained in care for more than 16 weeks. Documentation of patient outcome measures on the CRF was inconsistent. The clinician-rated sympom severity item was the only symptom item reported with high consistency, at 91 percent of the time. QIDS-SR and CGI scores were reported for 39 percent and 58 percent of the patients, respectively.

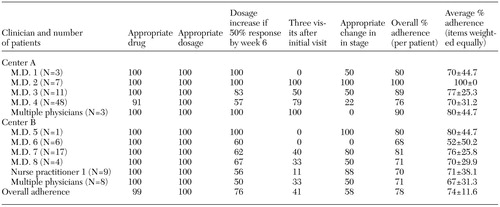

An appropriate antidepressant regimen, as specified by the TIMA depression algorithm, was prescribed for all but two patients. Clinicians had 100 percent adherence in prescribing minimum therapeutic medication dosages. Adherence to the report card item "dosage increase" was high but varied between clinicians and between sites. Adequate frequency of visits and appropriate changing of stages were the two least consistently followed adherence measures. Overall adherence to the algorithm was 78 percent. When all items were weighted equally (clinicians and report card items), the average percentage adherence to the algorithm was 74 percent. Report card percentage adherence scores are listed in Table 1.

Discussion

Overall, clinicians' adherence to the algorithm was fairly high. However, not all clinicians consistently attempted to optimize outcomes by increasing antidepressant dosage in a timely fashion when patients' symptoms were inadequately responding, and clinicians' adherence to visit frequency and moving to the next algorithm stage was variable.

Variance from an algorithm may not always be an indication that a clinician is not intending to adhere to the algorithm but may reflect a clinician's functioning within an organization (7). Resources with which to provide care vary from clinic to clinic, as do organizational structure and clinic culture. The organization's role in providing the necessary resources, leadership, planning, and infrastructure to change processes are critical if implementation of any new service program is to occur. In addition, continued surveillance of adherence and outcome measures through quality management programs are necessary (8).

Documentation of individual patient outcome measures was inconsistently reported at both centers. Systematic, quantitative assessment and documentation of outcomes is a relatively new phenomenon in psychiatry and certainly was new to the clinicians in this study (9). These results suggest that additional supports are needed in community mental health centers to promote the systematic documentation of patient outcomes. However, it is not clear whether inadequate documentation is tied to inadequate staff resources, clinic organization, clinician attitudes, or other issues.

We found a high rate of patient attrition from care (57 percent) at 120 days. Although clinicians' adherence scores were not penalized when patients dropped out of care prematurely, this is clearly an issue that needs to be addressed in this population of patients who have largely recurrent depression. It is possible that patients who dropped out of care either responded poorly to treatment, responded well initially and then saw no need for continuing services, or were dissatisfied with services at the clinic.

In general, patient adherence to treatment appears poor among persons with depression. Although the CRF contains a check box for clinicians' assessment of a patient's medication adherence, past studies have indicated that clinicians often overestimate adherence (10). Patient nonadherence is an uncontrolled variable that can affect variance of outcomes.

Another potential limitation of this study was that the report card weighted all items equally. It is feasible that one measure influences or is more predictive of patient outcomes than others. In addition, scores on individual items may be dependent on one another. For example, if the frequency of visits is inadequate, dosage increases may not be possible. Similarly, clinic organizational structure and resources may not allow for adequate visit frequency.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that a medication algorithm can be implemented with reasonably high clinician adherence in community mental health centers. The degree to which patient outcomes are associated with adherence to the algorithm could not be evaluated in this study and is an important subject for future research.

Dr. Bettinger and Dr. Crismon are affiliated with the College of Pharmacy of The University of Texas at Austin, 1 University Station, MC A1910, Austin, Texas 78712 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Crismon is also with the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation in Austin, with which Dr. Shon is affiliated. Dr. Trivedi and Dr. Grannemann are with the department of psychiatry of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

|

Table 1. Percentage adherence scores for individual items on the clinician report card in a study of adherence to the major depressive disorder algorithm of the Texas Implementation of Medication Algorithms

1. Rush AJ, Crismon ML, Kashner M, et al: Texas Medication Algorithm Project: Phase III (TMAP-III): rationale and design. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:357–369, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Starkweather K, Shon S, Crismon ML: A Texas-sized prescription. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow 9(4):44–46, 2000Google Scholar

3. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, et al: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomotology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomotology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine 34:73–82, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Crismon ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, et al: The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:142–156, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Trivedi MH, Shon S, Crismon ML, et al: TIMA Physician Procedural Manual: Guidelines for Treating Major Depressive Disorder. Austin, Tex, TDMHMR, 2000. Available at www.mhmr.state.tx.us/centraloffice/medicaldirector/timamddman.pdfGoogle Scholar

6. National Committee for Quality Assurance: HEDIS 2000: Technical Specifications, vol 2. Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2000Google Scholar

7. Miller AL, Crismon ML, Hall CS, et al: Avances in psychopharmacology and pharmacoeconomics, in Mental Health Services: A Public Health Perspective. Edited by Levin B, Petrila J. New York, Oxford University Press, 2004Google Scholar

8. Lin EH, Katon WJ, Simon GE, et al: Achieving guidelines for the treatment of depression in primary care. Medical Care 35:831–842, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Chuang WC, Crismon ML: Evaluation of a schizophrenia medication algorithm in a state hospital. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 60:1459–1467, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. O'Donnell C, Donohoe G, Sharkey L, et al: Compliance therapy: a randomized controlled trial in schizophrenia. British Medical Journal 327:834–837, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar