Variations in Use of Second-Generation Antipsychotic Medication by Race Among Adult Psychiatric Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined variations in the use of second-generation antipsychotic medication among African-American and non-Hispanic white patients in a national sample of adults who were treated by psychiatrists. METHODS: This study used data from studies of psychiatric patients and treatments that were conducted by the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's (APIRE's) Practice Research Network (PRN). Psychiatrists provided detailed clinical data for 126 African-American patients and 574 white patients who were randomly selected and for whom antipsychotic medications were prescribed. The study assessed differences by race in the use of second-generation antipsychotic medication, adjusting for clinical, sociodemographic, and health-system characteristics, including patients' source of payment for treatment. RESULTS: African-American patients were less likely than white patients to receive second-generation antipsychotic medications (49 percent compared with 66 percent). After the analysis statistically adjusted for clinical, sociodemographic, and health-system characteristics, African-American patients remained less likely than white patients to receive second-generation antipsychotics. CONCLUSIONS: Because African Americans tended to receive medications that are not first-line recommended treatments and that have a greater risk of producing tardive dyskinesia and extrapyramidal side effects, African Americans could be expected to suffer diminished clinical status. This disparity may also contribute to lower rates of adherence and to more frequent emergency department visits and psychiatric hospitalizations among African Americans

Racial and ethnic variations in pharmacotherapy have been documented in recent studies, indicating that African Americans may be less likely than whites to receive second-generation antipsychotic medications or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (1,2,3). After patient demographic and service use characteristics were controlled for, Kuno and Rothbard (4) observed racial differences in types of antipsychotic medications that were prescribed to a sample of Medicaid recipients. Explanations offered for these variations relate to physicians' skills, knowledge, and treatment preferences as well as to metabolic differences between racial and ethnic groups and to economic and health-system factors.

Although studies are inconclusive, some evidence indicates that African Americans metabolize antipsychotics more slowly than whites. This difference in metabolism can result in a faster and higher response rate to the medication and increased side effects when African Americans are treated with dosages that are commonly used for white patients (5). In contrast, Ruiz and colleagues (6) suggested that if weight is taken into consideration, African-American patients need the same dosages of antipsychotic medications as white patients and Hispanic patients need lower dosages than white or African-American patients in order to attain a similar response. Frackiewicz and colleagues (7) observed that although research that relates to the use of antipsychotics among African Americans is limited, some studies suggest that racial differences may be due to clinicians' biases and prescribing practices rather than to pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic variability.

Financial barriers may be related to lower use of second-generation antipsychotics among African Americans. African Americans are less likely to have health insurance, more likely to be publicly insured, and less likely to have private insurance than whites (8). Compared with whites, African Americans tend to have a more limited choice of insurance plans and rely to a greater extent on emergency departments (9). The higher cost of second-generation antipsychotics may require trials that show that conventional antipsychotics are not as effective as second-generation antipsychotics before some health plans or public treatment systems initiate the use of second-generation antipsychotics (10). In addition, the Surgeon General's report on culture, race, and ethnicity concluded that African Americans experience significantly more limited access to health care across all income levels than whites (11).

Other racial and ethnic differences in pharmacotherapy have been reported, indicating that African Americans receive higher dosages of antipsychotics (12,13,14,15) and are more likely to receive long-acting depot medications (4,13). These differences were observed across treatment settings, including psychiatric emergency departments (15) and inpatient settings (16). The Schizophrenia Patient Outcome Research Team showed that African Americans were less likely than white patients to receive treatment in concordance with recommended practices (17).

The research literature indicates racial disparities in pharmacotherapy, but it suffers from important limitations. No study with a sufficient sample size has focused on a nationally representative sample of adults who are treated by psychiatrists, and no study has used an extensive set of variables to control for patients' clinical, sociodemographic, and health plan factors. In addition, previous studies have not paid sufficient attention to differences in the quality of pharmacotherapy—specifically, whether African Americans are treated with conventional medications that are generally considered less desirable because of the greater side effect profiles of the medications (18,19,20,21,22). Side effects that occur with greater frequency with conventional antipsychotics, such as tardive dyskinesia and extrapyramidal symptoms (23), not only compromise patients' health but may also make it less likely that patients for whom conventional antipsychotics are prescribed will continue to appropriately take the medications. Glazer and colleagues (13) reported that African-American patients had nearly twice the rate of tardive dyskinesia as white patients, indicating that second-generation medications—which are associated with a lower incidence of tardive dyskinesia (24)—may be better tolerated by African Americans when an antipsychotic medication is indicated. Additionally, the likelihood of excessive dosing is reduced when second-generation antipsychotics are prescribed (12).

Our study investigated differences in the use of second-generation antipsychotics among adult African-American and white patients for whom antipsychotic medication was prescribed by using patient data that were provided by a large national sample of psychiatrists. Our study controlled for patients' sociodemographic characteristics as well as clinical factors, treatment setting factors, and system-of-care factors that may be correlated with the use of antipsychotic medication. On the basis of previous research, we hypothesized that second-generation antipsychotics would be prescribed for African-American patients less frequently than for white patients and that publicly insured patients would receive second-generation antipsychotics less frequently than privately insured patients.

Methods

Background

Our study used data from the 1997 and 1999 studies of psychiatric patients and treatments that were conducted by the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's (APIRE's) Practice Research Network (PRN). Data from 1997 and 1999 were combined to provide adequate sample sizes for subgroup analyses. Pincus and colleagues (25) provided a detailed description of the methods and implementation of the 1997 study. Psychiatrists were eligible to join the PRN if they were members of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and if they spent 15 or more hours a week in direct patient care when the survey was conducted. The PRN consisted of 784 psychiatrists in 1999 and 518 psychiatrists in 1997. In 1999, 47 percent (N=378) of the PRN members were randomly selected and recruited from the APA membership to ensure that the PRN had a representative sample across settings; the remainder of PRN members (406 members, or 53 percent) were self-selected volunteers who were recruited through a nationwide effort. Volunteers responded to advertisements in APA publications and at national psychiatric conferences to join the PRN. In 1997, 42 percent (N=224) of the PRN members were randomly recruited from the APA membership, and the remainder (307 members, or 58 percent) were self-selected. The response rates for the studies were 78 percent (N=615) in 1999 and 79 percent (N=417) in 1997.

After approval by the APA institutional review board and local institutional review boards when appropriate, all PRN members were asked to complete the study of psychiatric patients and treatments in 1997 and 1999, which consisted of a survey that captured patient-level data on the characteristics of psychiatric patients who were treated in routine clinical settings (25). Written informed consent was obtained from psychiatrists who participated in the studies. However, because no names or information identifying the patients was collected, the institutional review boards did not require patients' written informed consent. Psychiatrists were randomly assigned to begin data collection at one of 14 start times within a one-week period. Psychiatrists were then asked several questions about 12 patients who were seen consecutively after their assigned start time. The 12 patients provided the sampling frame for selecting three patients for whom additional detailed information was obtained. The sampling method has been described in detail elsewhere (25). In total, psychiatrists provided detailed demographic and clinical data for 3,088 patients. Our study focused on white and African-American patients over the age of 18 years for whom conventional or second-generation antipsychotic medication was prescribed (N=700).

We created sampling weights to generate nationally representative estimates. The weights adjusted for differences between the random and volunteer PRN samples and differences between PRN members and APA members. The weights also accounted for the probability of a patient's being selected for the study on the basis of a psychiatrist's caseload. All analyses used SUDAAN statistical software to accommodate the complex sampling design of the study and the sampling weights.

All data were psychiatrist reported —that is, the data were based on the psychiatrist's clinical judgment and impressions. Study measures included patients' sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, race and ethnicity, gender, marital status, number of years of education, and employment status. Data were obtained on diagnostic and clinical characteristics, such as DSM-IV axis I and II mental disorders, general medical conditions, psychosocial problems and Global Assessment of Functioning scores, severity of symptoms, and whether patients had a previous psychiatric hospitalization. For severity of symptoms, psychiatrists were asked to rate the level of patients' current psychotic symptoms; options were none, mild, moderate, or severe. System-of-care measures were obtained, such as treatment setting, patients' source of payment for the index visit, and psychiatrists' region of practice. Psychiatrists reported prescribing the following second-generation antipsychotics at the time of this study: clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone. Conventional antipsychotics included chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, loxapine, mesoridazine, molindone, perphenazine, thioridazine, thiothixene, and trifluoperazine.

Analytic plan

Weighted bivariate cross-tabulations (Taylor chi square test for categorical variables at <.05 significance level) assessed differences in the use of second-generation and conventional antipsychotics by race or ethnicity among patients with various sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and health plan arrangements. Multiple logistic regression analyses assessed the likelihood of receiving a second-generation antipsychotic by adjusting for the severity of patients' clinical symptoms, sociodemographic factors, and health-system factors.

Results

Patient sample

Our study focused on white and African-American adult patients for whom conventional second-generation antipsychotics were prescribed (N=700). Psychiatrists reported that, of these 700 patients, 18 percent (N=126) were African American. Half the patients in our study sample (357 patients, or 51 percent) were men; the mean±SD patient age was 47.5±20.6 years; and the mean number of years of education was 12.4± 4.3 years. Twenty-two percent of the patients (N=154) were enrolled in Medicaid, 31 percent (N=217) in Medicare, and 17 percent (N=119) in private insurance; 23 percent (N=161) did not have any health insurance. Fifty-four percent of the patients (N=378) were reported to have schizophrenia, 21 percent (N=147) depressive disorder, 18 percent (N=147) bipolar disorder, and 8 percent (N=56) dementia. Twenty-seven percent of the patients were reported to have a substance use disorder.

Overview

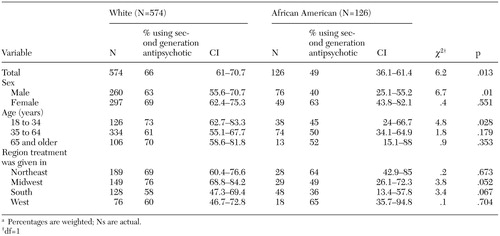

A total of 441 patients in our sample (63 percent) received a second-generation antipsychotic. As Table 1 shows, African-American patients were significantly less likely than white patients to receive second-generation medications (49 percent compared with 66 percent). For both years studied, fewer African Americans than whites received second-generation antipsychotics; 37 percent of African Americans (N=19) received second-generation medication in 1997, compared with 56 percent of white patients (N=125), and 58 percent of African-American patients (N=43) received second-generation medication in 1999, compared with 72 percent of white patients (N=252).

Sociodemographic characteristics

Among female patients, African Americans and whites had similar rates of second-generation antipsychotic use; however, statistically significant differences were observed among male patients (Table 1). Racial differences were also noted among young adults aged 18 to 34 years; almost three quarters of young white patients (73 percent) received second-generation medications, compared with less than half of young African-American patients (45 percent). As Table 1 shows, comparable rates of second-generation antipsychotic medication use were observed for African-American and white patients whose psychiatrists practiced in the Northeast and the West. However, in the Midwest a smaller proportion of African Americans received second-generation antipsychotics compared with whites. In the South racial differences were not statistically significant.

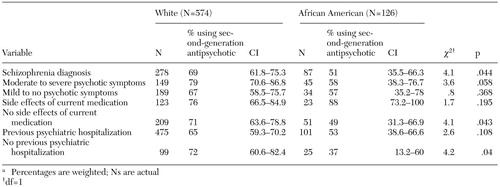

Clinical characteristics

As shown in Table 2, among patients who were given a diagnosis of a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder, African Americans received second-generation antipsychotics at a significantly lower rate than white patients: 69 percent of white patients compared with 51 percent of African-American patients. Among patients with moderate or severe psychotic symptoms, African Americans had a lower rate of second-generation antipsychotic medication use than whites, although the comparison showed only a trend toward significance. Differences in medications by race among patients with mild or no psychotic symptoms were less pronounced and not statistically significant. Among patients who reported side effects from their current medication, no differences by race were observed in the use of second-generation medications. Among patients who did not have side effects reported from their current medication, 49 percent of African Americans had second-generation medications prescribed, compared with 71 percent of white patients. No statistically significant differences were observed among patients who had a previous psychiatric hospitalization. However, among patients who had no history of psychiatric hospitalization, 72 percent of white patients received second-generation medications, compared with only 37 percent of African Americans.

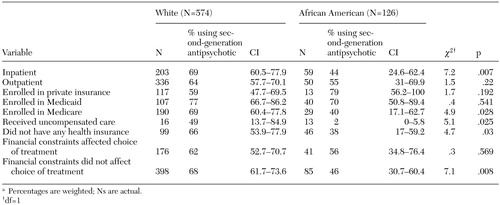

Treatment setting and health system characteristics

As Table 3 shows, about two-thirds of white inpatients (69 percent) and less than half of African-American inpatients (44 percent) received second-generation medications. No statistically significant differences were observed among outpatients. Rates of second-generation medication use among African Americans who were enrolled in Medicaid or private insurance were comparable with those of white patients. African Americans who were enrolled in Medicare, who did not have health insurance, or who received uncompensated care had significantly lower rates of second-generation medication use than white patients. Among patients whose psychiatrist reported that financial considerations—for example, managed care limitations or limitations of a public system—resulted in patients' receiving a different form of treatment than the psychiatrist preferred, no differences by race were observed (Table 3). However, among patients whose treatments were not affected by financial considerations, African-American patients had a significantly lower rate of second-generation medication use than white patients.

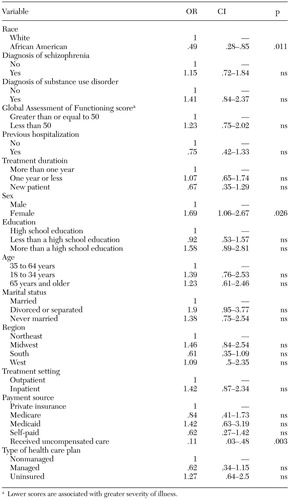

Multivariate analysis

As can be seen in Table 4, African Americans were half as likely as whites to receive second-generation medications after the analysis adjusted for clinical, sociodemographic, and health plan factors. Female patients were significantly more likely to receive second-generation medications than male patients. Results of gender-stratified multiple regression analyses indicated that African-American men were 65 percent less likely than white men to receive second-generation antipsychotics (odds ratio [OR]=.34, 95 percent CI=.17−.74, p<.01). However, no significant differences by race were observed among women. Also, patients who received uncompensated treatment were 89 percent less likely than privately insured patients to receive second-generation medications. No other covariates in the model were statistically significant.

Discussion

Among adult patients who were identified as needing antipsychotic medication treatment, African Americans were less likely than whites to receive second-generation antipsychotics. Because second-generation antipsychotics are generally considered the treatment of choice, it can be argued that African-American patients tend to receive a lower quality of psychopharmacologic treatment compared with white patients (26,27,28,29).

Our study identified specific groups of patients who were less likely to receive newer medications. Among the various subgroups, we found that African-American patients who were male, who were younger, or who had schizophrenia were significantly less likely to receive second-generation antipsychotics than white patients from these subgroups. Younger patients may be particularly good candidates for second-generation medications, because these medications are associated with a decreased risk of extrapyramidal side effects and tardive dyskinesia. However, even though we found that younger white patients tended to be given prescriptions of second-generation antipsychotics more frequently than older white patients, we found that fewer younger African Americans than older African Americans were given prescriptions of second-generation medications.

Differences in medications by race were observed among inpatients but not among outpatients. This difference may be related to the greater severity of illness among African-American outpatients compared with white outpatients that was observed in our study—for example, lower Global Assessment of Functioning scores. A greater severity of illness may be associated with a higher perceived need for second-generation antipsychotics.

In addition to clinical and sociodemographic factors, health-system factors were also considered. Although other state-level studies that used claims data found racial disparities in pharmacologic treatment among Medicaid recipients (2,4), our study did not replicate this finding. Our study found that African-American and white patients who were enrolled in Medicaid had comparable rates of second-generation antipsychotic medication use. Racial disparities were observed among patients who were enrolled in Medicare and among those who did not have any health insurance, indicating that health-system factors may affect choice of antipsychotic. Patients who are enrolled in Medicare or who do not have health insurance may need additional resources, such as supplemental insurance coverage or other economic resources, to obtain second-generation antipsychotics.

After our analysis controlled for health plan factors in the multivariate model, African-American patients remained half as likely as white patients to receive second-generation antipsychotics, indicating that patients' race is associated with the use of second-generation medications after the source of health care payment is accounted for. However, socioeconomic status may also contribute to racial differences in use of second-generation medication. Residual confounding may have occurred in the limited data elements that were available to adjust for socioeconomic status—for example, education level and insurance type. Our study found that women were 1.7 times as likely as men to receive second-generation antipsychotics, which suggests that both race and gender predict the use of second-generation antipsychotics. Racial disparities were even more evident when only men were included in the gender-stratified analysis (OR=.34 for men compared with OR=.49 overall) and racial disparities among female patients were not observed, which suggests that African-American women may be receiving second-generation antipsychotics at rates comparable to those for white women.

As summarized in the Surgeon General's report (11), African Americans in treatment are less likely than whites to receive an accurate diagnosis of depression. The prescribing psychiatrists in our study may have recognized and treated mood symptoms more frequently among white patients and prescribed second-generation antipsychotic medications. The disparities in medication use may be related to disparities in symptom recognition rather than to choosing different medications solely on the basis of racial factors, independent of diagnoses.

Multivariate analysis also indicated that patients who received uncompensated care were much less likely to receive second-generation antipsychotics than patients who were privately insured. This difference would be expected to have a greater impact on African Americans, because only 3 percent of white patients received care that was uncompensated, compared with 10 percent of African-American patients. For facilities that provide uncompensated care, costs of second-generation antipsychotics may be prohibitive. However, conventional antipsychotics may be related to increased long-term costs, because research indicates that patients who are discharged while they are taking conventional antipsychotics have higher relapse rates compared with patients who are discharged while they are taking second-generation medications (18). Promoting creative strategies that encourage the prescription of second-generation antipsychotics at facilities that predominately prescribe conventional antipsychotics may reduce some of the racial differences in antipsychotic medication treatment as well as increase the cost-effectiveness of treatments by lowering relapse rates.

African-American patients with mental illness represent an underserved population, and considering the finding that African Americans may be more vulnerable to developing tardive dyskinesia (13), our study findings are disturbing. Overmedication, as reported in previous studies (12,30), combined with the disproportionate use of conventional antipsychotics that was observed in our study, may place African Americans at increased risk of extrapyramidal side effects and tardive dyskinesia.

Our study was limited because it relied exclusively on psychiatrists' clinical judgment, with no independent diagnostic validation or data reported directly by patients. Data on patient income would have allowed for a more precise measurement of the effect of socioeconomic status. Our study was also limited by relatively small sample sizes, which precluded analyses for Hispanic, Asian-American, and other subgroups of interest. Additionally, small sample sizes for subgroup analyses of patients who were enrolled in private insurance or of patients' region of residence suggest that our results should be interpreted cautiously.

Conclusions

The PRN study provided a national sample of psychiatric patients, which allowed us to systematically examine variation in the use of second-generation antipsychotic medication and to assess differences after the analysis adjusted for clinical, sociodemographic, and system factors. Although the samples were small, African Americans who were enrolled in private insurance or Medicaid appeared to be able to gain access to second-generation medications at rates comparable to those of white patients. Patients who received uncompensated care were the least likely to receive second-generation antipsychotics. Differences by race remained after the analysis adjusted for type of insurance. However, larger samples, particularly for African Americans who are privately insured, would allow for further exploration of insurance-related differences in the use of second-generation antipsychotics. Future research is needed not only to explain race- and gender-related differences in pharmacotherapy but also to document the consequences. Insofar as African Americans tended to receive antipsychotic medications that are generally not considered first-line recommended agents, African Americans are at risk of receiving lower quality of care and experiencing poorer outcomes of care, which could translate into a decreased capacity to perform successfully at work or with family and friends. Although the superiority of second-generation antipsychotics is currently being debated (22), a tendency to receive what is considered to be suboptimal medications could contribute to greater emergency department use and higher rates of psychiatric hospitalization among African Americans, which has been observed in previous studies. Further investigation is needed to determine the causes and consequences of disparities in pharmacotherapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by contract 280-01-8056 from the Center for Mental Health Services and grants from the American Psychiatric Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Practice Research Network (PRN) psychiatrists contributed their time to participate in the 1997 and 1999 PRN Study of Psychiatric Patients and Treatments. The authors thank David Granger for his input on these analyses, and statistical consultants Maritza Rubio Stipec, Sc.D., and Donald S. Rae, M.A.

Ms. Herbeck is affiliated with the University of California, Los Angeles, Integrated Substance Abuse Programs in Los Angeles. Dr. West and Dr. Duffy are with the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's (APIRE's) Practice Research Network in Arlington, Virginia. Ms. Ruditis is with the Center for Mental Health Services in Rockville, Maryland. Ms. Fitek is with George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. Dr. Bell is with the Community Mental Health Council, Inc., in Chicago. Dr. Snowden is with the Center for Mental Health Services Research and School of Social Welfare at the University of California, Berkeley.Send correspondence to Dr. West at 1000 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1825, Arlington, Virginia 22209 (e-mail, [email protected]). Preliminary results were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, held May 19 to 23, 2002, in Philadelphia.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients using second-generation antipsychotics, by racea

a Percentages are weighted; Ns are actual.

|

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of patients using second-generation antipsychotics, by racea

a Percentages are weighted; Ns are actual

|

Table 3. Treatment setting and health-system characteristics for patients using second-generation antipsychotics, by racea

a Percentages are weighted; Ns are actual.

|

Table 4. Likelihood of use of second-generation antipsychotics after the analysis adjusted for clinical, demographic, and system factors

1. Mark TL, Dirani R, Slade E, et al: Access to new medications to treat schizophrenia. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 29:15–29, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Melfi CA, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, et al: Racial variation in antidepressant treatment in a Medicaid population. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:16–21, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wang PS, Zarin DA, West JC, et al: Recent patterns and predictors of antipsychotic medication regimens used to treat schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:451–457, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kuno E, Rothbard AB: Racial disparities in antipsychotic prescription patterns for patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:567–572, 2002Link, Google Scholar

5. Lawson WB: Racial and ethnic factors in psychiatric research. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:50–54, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Ruiz P, Varner RV, Small DR, et al: Ethnic differences in the neuroleptic treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly 70:163–172, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Frackiewicz EJ, Sramek JJ, Herrera, et al: Ethnicity and antipsychotic response. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 31:1360–1369, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kass B, Weinick R, Monheit A: Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Chartbook No. 2. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1999Google Scholar

9. Phillips KA, Mayer ML, Aday LA: Barriers to care among racial/ethnic groups under managed care. Health Affairs 19(4):65–75, 2000Google Scholar

10. Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Dunn LB, et al: Antipsychotic medication adherence: is there a difference between typical and atypical agents? American Journal of Psychiatry 159:514, 2002Google Scholar

11. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2001Google Scholar

12. Walkup JT, McAlpine DD, Olfson M, et al: Patients with schizophrenia at risk for excessive antipsychotic dosing. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:344–348, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Glazer WM, Morgenstern H, Doucette J: Race and tardive dyskinesia among outpatients at a CMHC. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:38–42, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Marcolin MA: The prognosis of schizophrenia across cultures. Ethnicity and Disease 1:99–104, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

15. Segal SP, Bola JR, Watson MA: Race, quality of care, and antipsychotic prescribing practices in psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatric Services 47:282–286, 1996Link, Google Scholar

16. Chung H, Mahler JC, Kakuma T: Racial differences in treatment of psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 46:586–591, 1995Link, Google Scholar

17. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11–32, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Rabinowitz J, Lichtenberg P, Kaplan Z, et al: Rehospitalization rates of chronically ill schizophrenic patients discharged on a regimen of risperidone, olanzapine, or conventional antipsychotics. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:266–269, 2001Link, Google Scholar

19. Janicak PG, Keck PE Jr, Davis JM, et al: A double-blind, randomized, prospective evaluation of the efficacy and safety of risperidone versus haloperidol in the treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 21:360–368, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Gomez JC, Crawford AM: Superior efficacy of olanzapine over haloperidol: analysis of patients with schizophrenia from a multicenter international trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62 (suppl 2):6–11, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

21. Campbell M, Young PI, Bateman DN, et al: The use of atypical antipsychotics in the management of schizophrenia. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 47:13–22, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, et al: Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systemic overview and meta-regression analysis. British Medical Journal 321:1371–1376, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Caroff SN, Mann SC, Campbell EC, et al: Movement disorders associated with atypical antipsychotic drugs. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63(suppl 4):12–19, 2002Medline, Google Scholar

24. Bullock R, Saharan A: Atypical antipsychotics: experience and use in the elderly. International Journal of Clinical Practice 56:515–525, 2002Medline, Google Scholar

25. Pincus HA, Zarin DA, Tanielian TL, et al: Psychiatric patients and treatments in 1997: findings from the American Psychiatric Practice Research Network. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:441–449, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, et al: Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:255–262, 2002Link, Google Scholar

27. The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of schizophrenia 1999. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 11):3–80, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

28. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). American Journal of Psychiatry 159(4 suppl):1–50, 2002Google Scholar

29. Sixteen State Pilot Study State Mental Health Agency Performance Measures. Rockville, Md, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute, Inc, Center for Mental Health Services, Feb 27, 2001Google Scholar

30. Lawson WB: Clinical issues in the pharmacotherapy of African-Americans. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 32:275–281, 1996Medline, Google Scholar