Clinical Computing: Using Information Systems to Improve Care for Persons With Schizophrenia

Abstract

Introduction by the column editor: The biggest obstacle to harvesting the advantages of information technology systems to guide best practice has been psychiatrists' reluctance. To make algorithms efficient for physician use, electronic medical records will have to proceed or accompany the systems that guide improved care. The MINT project, which piggybacks onto the existing VA electronic medical record system, is an example that should help light the way.

The Institute of Medicine has stated that information technology has "enormous potential" to improve the quality and efficiency of health care (1). Although there have been remarkable successes (2), national dissemination of information technology in health care has been slow. This has certainly been the case in the mental health field, and organizations that provide care for persons with severe and persistent mental illness have had difficulty making progress.

A notable exception is the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which has implemented a uniform fully electronic national record system called the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). The VA has begun to use this infrastructure to improve patient safety and use of preventive services. The VA is the nation's largest integrated health care system, and each year it provides care to more than 100,000 persons with schizophrenia. This column reports on the Medical Informatics Network Tool (MINT), a system that builds on CPRS to improve the treatment of schizophrenia. MINT has been implemented at two large VA health care centers in southern California, where it is being evaluated.

Over the past decade, new medication and psychosocial treatments have been shown to improve outcomes among patients with schizophrenia (3). New antipsychotic medications have better safety and efficacy profiles, and specific rehabilitation technologies allow many persons to return to work. Assertive community-based care can allow people with severe illness to live successfully in the community. Unfortunately, a large proportion of persons with schizophrenia have yet to benefit from these treatment advances (4). Many have clinical needs that are not being addressed, and methods are needed to improve the quality of care.

In theory, it should be possible to improve care for schizophrenia by identifying patients who would benefit from each evidence-based intervention and ensuring that the intervention is available to them. In reality, this has proven to be very difficult. One of the leading national efforts to improve care has been the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) (5). Founded in 1998, the mission of QUERI is to improve health care outcomes by systematically implementing evidence-based practices in routine practice settings.

When QUERI leaders have focused on schizophrenia, they have found that the major challenge to improving care is a lack of valid, routinely collected outcomes data (6). Lack of such data for other medical conditions has been less of a problem. For example, medical records routinely include data needed to improve care for hypertension, including data on vital signs, demographic characteristics, medications, and comorbid medical disorders. To improve care for schizophrenia, it is necessary to know which patients have unmet needs and to have information about psychotic symptoms, medication side effects, functional deficits, and co-occurring problems, such as substance abuse and homelessness. Unfortunately, documentation of these domains in medical records is highly erratic and often entirely absent (7).

Overview of MINT

The MINT system was developed to solve the problem of the lack of information about patients with schizophrenia by making routine outcomes data a component of daily practice. MINT provides clinicians with patient-specific data and access to scientific information in real time, during the patient encounter. It provides reports for clinicians on the clinical status of their patients and reports for managers on the population of patients in treatment. MINT includes both a Web browser interface for entry and management of structured patient data and PC-based applications that interact with clinicians during the patient encounter.

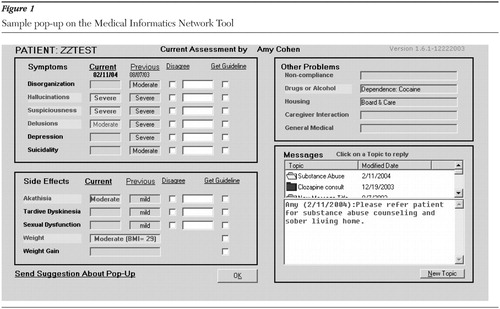

At each patient visit, a nurse briefly assesses symptoms, side effects, and other key problems and enters these "psychiatric vital signs" into a database using a password-protected Web browser interface. When the psychiatrist opens the patient's electronic medical record, MINT displays a pop-up window that interacts with the clinician (Figure 1). The pop-up provides information from recent assessments and highlights key problems. With one click, summaries of relevant treatment guidelines are displayed, along with Internet links to complete guidelines. The interface also facilitates communication among team members via a secure messaging system.

MINT is currently being used to support Enhancing Quality Utilization in Psychosis (EQUIP), a research project funded by the VA Health Services Research and Development Service. EQUIP is a randomized controlled trial at two VA health care centers of an intervention designed to improve care for persons with schizophrenia. The EQUIP intervention is based on established principles for managing chronic illness (8). Its goal is to establish collaboration between a proactive treatment team and activated patients and caregivers. To provide effective care for patients with chronic illness, researchers have found that it is important to adopt care models that reach beyond individual clinicians' practices to integrate greater availability of clinical information, reorganize the practice system and clinicians' roles, and focus on evidence-based protocols. Although clinicians and patients can become accustomed to morbidity, effective care requires continued clinical assessment and access to needed treatments. Follow-up must be active and sustained and must ensure that effective preventive and medical interventions occur.

Implemention and evaluation

MINT was implemented in January 2003 at clinics of the Greater Los Angeles and Long Beach VA health care centers. Half of the psychiatrists at each site were randomly assigned to an intervention that included MINT and the EQUIP intervention. After four months, case managers at the clinics asked to receive the MINT pop-up when they had patients in common with the intervention psychiatrists. The case managers were included at this point. As of January 2004, MINT has been used by more than 28 psychiatrists, six case managers, and two nurse quality coordinators to manage the care of more than 300 patients.

Nine months after implementation of MINT, a sample of 18 of the psychiatrists and case managers in the intervention group (53 percent) were interviewed by an independent researcher about their utilization of the information system and its usefulness. The interview included an established informatics usability questionnaire (9) and qualitative items about the psychiatric vital sign assessments, the messaging system, the links to treatment guidelines, and the impact of MINT on the treatment provided to patients.

Nearly all psychiatrists found the information system intuitive and easy to use and believed that it provided relevant clinical information in a visually appealing format. Virtually all stated that they learned important new information about their patients, especially about patients' social circumstances. Most stated that the assessment data reminded them to discuss side effects and medical problems with their patients. Some psychiatrists specifically stated that having the additional information led to a better level of patient care. Links to treatment guidelines were used solely by psychiatrists, and the messaging system was used mostly by case managers and care coordinators to communicate information to psychiatrists. Overall, the psychiatrists stated that MINT provided them with specific information that they used to focus their treatment decision making.

Unlike the psychiatrists, a majority of case managers felt that they did not benefit substantially from information in MINT. Many stated that the information system seemed redundant because the data were already present in the medical record. Some stated that they were already aware of and doing everything to address this information and did not expect any changes in treatment as a result of the project. The case managers were skeptical about whether the psychiatrists read information in the pop-up and the messages, so they often sent e-mail and telephone messages to psychiatrists about patients. As a result of these interviews, the case managers have been more closely integrated into MINT; they now enter and manage patient data using the Web site.

Users have also sent feedback to the research team through a link in the pop-up. Feedback has ranged from suggestions about technical aspects, such as increasing font sizes, to suggestions for improving assessment information, such as adding a list of problems to be urgently addressed. Changes have been made on the basis of feedback. This process of quality enhancement appears to have promoted active participation of users and to have motivated them.

Nurse quality coordinators at each site have used MINT to oversee the care of the patients. The MINT Web site allows the nurses to maintain research and contact information for patients. Reports on the Web site allow them to see upcoming appointments, to identify patients with unmet needs for outreach and follow-up, and to communicate with other on-site team members by messaging. They can monitor clinicians' use of the pop-up, prompt clinicians when key care components have been overlooked, and intervene when other resources cannot be identified. Psychiatrists have been given Web reports that compare the unmet needs of their patients with those of other patients at the clinic.

Clinical managers at each site have used MINT reports to identify pervasive problems in care, monitor performance, and improve access to necessary treatments. For example, few prescriptions for clozapine were being written at one site even though a substantial number of patients had severe psychosis. MINT reports have led the site to established a centralized clozapine clinic and improve access to the medication. Both sites determined that they had a large proportion of patients who are overweight, but they had no services to offer patients with this problem. They have since begun to offer formal wellness programs.

Future applications

The MINT system has provided information that psychiatrists use to make clinical decisions about their patients with schizophrenia. It has led to enhanced communication and care oversight and has provided information for clinical managers. Future applications include extending the system to other disorders and more clinics. Although it was developed for patients with schizophrenia, it can be adapted for use with persons with other diagnoses, such as bipolar disorder. Because it is based on a Web interface and PC-based applications that interact with the standardized CPRS system, it should be easy to implement at other VA clinics. Although it was feasible to implement as part of the EQUIP project at two sites, further research is needed at sites with diverse staffing patterns, leadership, and norms and where local support is less consistent.

Extension of MINT to clinics outside the VA will require additional modifications. Many non-VA clinics have few nurses or psychologists available, and it may be difficult to find staff to assess patients' psychiatric vital signs. An alternative approach involves computerized patient self-assessment overseen by nonclinical staff. We recently completed a research project that found that patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder can accurately complete standardized instruments such as the BASIS by using a touch-screen computer interface with minimal or no supervision (unpublished data, Chinman MJ, Young AS, Schell, et al., 2003). It may be more difficult to implement MINT in the absence of a computerized medical records system. However, printed reports can be generated from MINT and handed to psychiatrists. PCs with an Internet connection are more prevalent, which allows broad use of the MINT Web system interface to oversee care provision and quality.

Systems such as MINT cannot, of course, make new services available. However, in the proper setting, MINT and similar programs can provide information that patients, caregivers, clinicians, and managers need to improve care and advocate for services that improve outcomes for persons with severe and persistent mental illness.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs and by grant MH-068639 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the UCLA-Rand Center for Research on Quality in Managed Care.

The authors are affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs Desert Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC), 11301 Wilshire Boulevard, 210A, Los Angeles, California 90073 (www.mirecc.org). Dr. Young and Dr. Mintz are also affiliated with the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute, Los Angeles. Joshua Freedman, M.D., is editor of this column.

Figure 1. Sample pop-up on the Medical Informatics Network Tool

1. Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2001Google Scholar

2. Bates DW, Leape LL, Cullen DJ, et al: Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA 280:1311–1316, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Herz MI, Marder SR: Schizophrenia: Comprehensive Treatment and Management. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002Google Scholar

4. President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health: Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Final Report. Available at www.mentalhealthcommission.gov/reports/reports.htm. Accessed Jan 21, 2004Google Scholar

5. Rubenstein LV, Mittman BS, Yano EM, et al: From understanding health care provider behavior to improving health care: the QUERI framework for quality improvement. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. Medical Care 38(6 suppl 1):I129-I141, 2000Google Scholar

6. Veterans Health Administration Quality Enhancement Research Initiative: Mental Health QUERI Strategic Plan. Available at www.mentalhealth.med.va.gov/mhq/exec-summary.shtml. Accessed Feb 4, 2004Google Scholar

7. Cradock J, Young AS, Sullivan G: The accuracy of medical record documentation in schizophrenia. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 28:456–465, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K: Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 288:1775–1779, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lewis JR: IBM Computer Usability Satisfaction Questionnaires: Psychometric Evaluation and Instructions for Use. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 7:57–78, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar