A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Community-Based Mental Health Outreach Services for Older Adults

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Psychiatric outreach services that provide mental health assessment and treatment to older adults in their homes or communities are widely promoted as improving access and outcomes for older adults. However, a systematic review of the efficacy of these services has not been done. This review evaluates the evidence base for the effectiveness of outreach services for older adults with mental illness in noninstitutional community settings. End points of interest include the ability of the outreach program to increase access to mental health services and improve psychiatric outcomes. METHODS: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Web-of-Science databases were searched for articles in English that were indexed through May 2004. Studies were included if they evaluated face-to-face psychiatric services provided to adults aged 65 and older with mental illness and if they were randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental outcome studies, uncontrolled cohort studies, or comparisons of two or more interventions. Articles were excluded that evaluated interventions that were provided in institutional settings or that focused on persons with dementia or their caregivers. RESULTS: Fourteen studies matched all the inclusion criteria. Two studies (one controlled prospective study and one study that used a comparison group) found support for the use of gatekeepers—nontraditional referral sources—in identifying socially isolated older adults with mental illness. Twelve studies (five randomized controlled trials, one quasi-experimental study, and six uncontrolled cohort studies) found that home and community-based treatment of psychiatric symptoms were associated with improved or maintained psychiatric status. All randomized controlled trials reported improved depressive symptoms, and one reported improved overall psychiatric symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: Limited data supported the effectiveness of outreach services in identifying isolated older adults with mental illness. A more substantial evidence base indicated that home-based mental health treatment is effective in improving psychiatric symptoms. Studies are needed that apply more rigorous methods evaluating the efficacy of case identification models and subsequent treatment for older persons with a variety of psychiatric diagnoses.

Older adults have historically underused mental health services. Low service use has been attributed to both personal and system barriers. To overcome these barriers and increase the use of mental health services, outreach models of care have been developed that provide services in settings where older adults reside or spend a significant amount of time. Outreach services have been nationally promoted as a means of improving access and mental health outcomes, yet their evaluation in older adult populations has been limited.

In less than ten years, the first of the baby-boom population will reach the age of 65 years (1). The aging of this population, especially the aging of persons with mental illness, is predicted to challenge the delivery of health care in an already impaired system. One in five older adults has a mental illness (2). The most prevalent conditions include anxiety and depressive disorders (3). Psychotic illnesses and substance abuse are less common (3). Projections indicate that the number of older adults with mental illness will more than double, from seven million in the year 2000 to 15 million by the year 2030 (2).

Untreated mental illness among older adults has a significant impact on health, functioning, and health service use and costs. For instance, late-life mental illness has been associated with impaired independent and community-based functioning, impaired cognition, poor medical and health outcomes, high medical comorbidity, increased disability and mortality, and compromised quality of life (4,5). Mental illness among older adults has also been correlated with increased use of health care, increased placement in nursing homes, increased burden on medical care providers, and higher annual health care costs (6,7,8,9,10).

In light of the significant burden of mental illness on older adults and on the health care system, the past 15 years have seen a dramatic increase in the knowledge of appropriate treatments for geriatric mental illness. A large body of data suggests that mental health interventions are successful in improving psychiatric outcomes of older adults with depression and dementia (11). A limited number of studies support the efficacy of interventions for late-life substance abuse, anxiety, and schizophrenia (11,12).

Despite the high prevalence of late-life mental illness and evidence for the efficacy of several pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions, mental illness is underrecognized and undertreated in this population. It is estimated that approximately half of older adults with a recognized mental disorder do not receive mental health services (13). Older adults are unlikely to use traditional clinic-based mental health services for a variety of reasons, including physical frailty, transportation difficulties, isolation, and stigma (14).

Poor access to mental health care has prompted national policy leaders to consider novel strategies for providing mental health services to older adults. Recent reports from the Administration on Aging (14), the Surgeon General (4), and the older adult subcommittee of the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (15) have promoted the provision of outreach services to older adults in noninstitutional community-based settings as a potential mechanism for increasing access to mental health care. These reports have described outreach services as the detection and treatment of mental health problems in settings where older adults live, spend time, or seek services. The primary elements of outreach services include case finding, assessment, referral, treatment, and consultation. For instance, outreach programs may offer early intervention, facilitate access to preventive health care services, provide evaluation services, refer individuals to community treatment or supportive services, and provide services designed to improve community tenure. Despite the national promotion of outreach services, a systematic review of their effectiveness has not been done. A systematic evaluation of this service delivery approach has implications for guiding national health care policy.

This review evaluates the evidence base surrounding the provision of psychiatric outreach to older adults in noninstitutional settings, as identified by models of case identification and mental health treatment. Specifically, this review addresses whether geriatric mental health outreach services are effective in improving access to mental health care through the identification of isolated older adults and in improving mental health symptoms or outcomes?

Methods

To identify relevant articles for this review, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Web-of-Science databases were searched within three topic areas for English language articles that were indexed through May 2004: community outreach services (keywords: "outreach," "gatekeeper," or "consultation and referral"), mental illness (keywords: "mental," "depress*", and "psych*"), and older adults (keywords: "geriatric," "late-life," or "elderly"). Additional articles were identified through bibliographic review and MEDLINE and Web-of-Science-related records searches.

Studies were included that evaluated face-to-face psychiatric outreach services provided to adults aged 65 and older with mental illness. Services included case-finding and identification programs as well as treatment that was provided in community-based noninstitutional settings, such as senior centers, senior residential care settings, and home-based settings. Studies were eligible if they were randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental outcome studies, uncontrolled cohort studies, or comparisons of two or more interventions.

Studies were excluded if they evaluated services that were provided in institutional settings—for example, nursing homes or hospitals. Because the goal of this review was to determine the effectiveness of outreach services for primary psychiatric disorders, interventions that explicitly focused on persons with dementia or their caregivers were excluded. Finally, we excluded articles that had at least one author in common and only minor differences with respect to study samples and efficacy results.

Selection of trials

A total of 145 articles were identified through the literature search, and 17 articles were identified through bibliographic and related records searches. A total of 104 articles were rejected because of sample selection (that is, a nongeriatric population), provision in an institutional setting, or lack of face-to-face contact. Forty additional articles were excluded on the basis of the quality of data presented: 36 contained only model descriptions or descriptive data, and four described small case studies. Among the 18 remaining reports, 14 fulfilled all inclusion criteria and four were excluded because they were published in duplicate. Among the 14 studies in our final sample, five studies were randomized controlled trials (16,17,18,19,20,21,22), one used a quasi-experimental design (23), one used a controlled prospective cohort (24), four used an uncontrolled prospective cohort (25,26,27,28), two used an uncontrolled retrospective cohort (29,30), and one provided outcome data on intervention and control cohorts (31,32,33).

Data extraction and analysis

Descriptive characteristics and outcome data were abstracted from the 14 reports that met all our inclusion criteria by using a standard data collection form. Data included study type, model description, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample characteristics, duration of the study, completion rate of the study, whether the intervention and outcome assessments were blind, study measures and outcomes, and strengths and weaknesses. Primary outcomes of interest included use of mental health services and improvement in psychiatric symptoms. Statistical aggregation of data was not feasible because of the lack of similarity among studies with respect to study design, inclusion criteria, sampling, and outcome measures.

Results

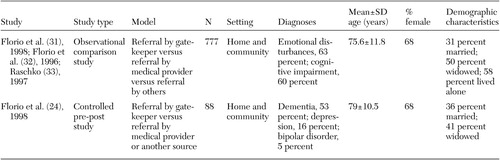

Effectiveness of case identification strategies

Studies evaluating the effectiveness of case identification models are summarized in Table 1. The studies highlight the gatekeeper model (nontraditional community referral sources) in comparison with traditional referral sources (medical providers, family members, informal caregivers, or other concerned persons). The gatekeeper model recruits community service personnel who have frequent contact with older persons, such as meter readers and utility workers, to identify and refer individuals for assessment. Assessment in both referral models focuses on identifying unmet needs and comprehensively evaluating physical health, mental health, and psychosocial needs. On the basis of identified needs, treatment recommendations are developed in concert with a multidisciplinary team.

Two evaluations that compared referrals by gatekeepers with those by traditional sources were identified, including one observational comparison study (31,32,33) and one controlled prospective study (24). Older adults evaluated in these studies had similar ages, gender distributions, and marital status. Diagnoses varied across studies. Often the studies had more individuals with a diagnosis of dementia or depression, as opposed to other diagnoses.

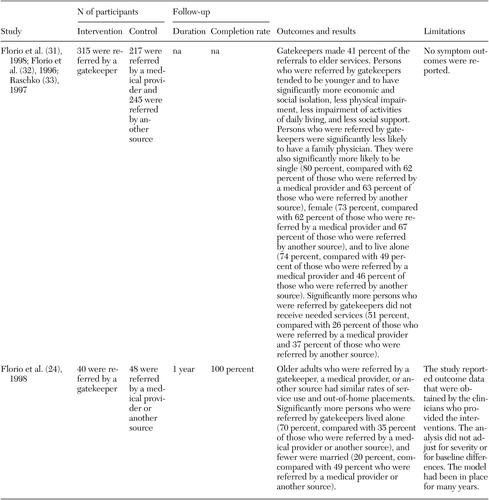

As shown in Table 2, gatekeepers identified approximately 40 percent of older persons referred to elder services. Differences were found in characteristics between individuals referred by gatekeepers and those referred by a medical provider or another traditional source. Older adults referred by gatekeepers were significantly more likely to live alone and were more often widowed or divorced. Moreover, individuals referred by gatekeepers were significantly more likely to be affected by economic and social isolation. These findings suggest that the gatekeeper approach reaches individuals who are less likely to gain access to services through conventional referral approaches. At the time of referral, individuals referred by gatekeepers were significantly less likely than individuals referred through traditional sources to use services. However, individuals from these two groups had similar service needs, which indicates that those referred by gatekeepers had a larger gap between services needed and services received (31,32,33). At the one-year follow-up, older persons referred by gatekeepers had no difference in service use or out-of-home placements compared with individuals referred by traditional sources. The authors concluded that older adults referred by gatekeepers do not place overly high service demands on the health care system (24).

Effectiveness in improving psychiatric symptoms and outcomes

Most evaluations of community-based mental health outreach models examine the impact of these services on symptoms and community tenure. These models generally employ a multidisciplinary team of providers to develop a care management protocol, which is implemented within a residential setting. Treatment recommendations vary significantly among individuals and are implemented through a variety of sources. Some outreach teams employ a model consisting of assessment and referral, whereas others directly implement treatment recommendations by clinicians on the assessment team.

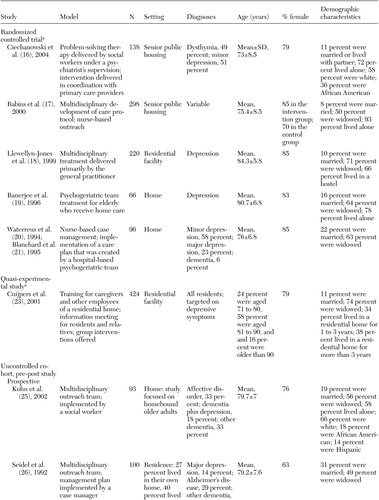

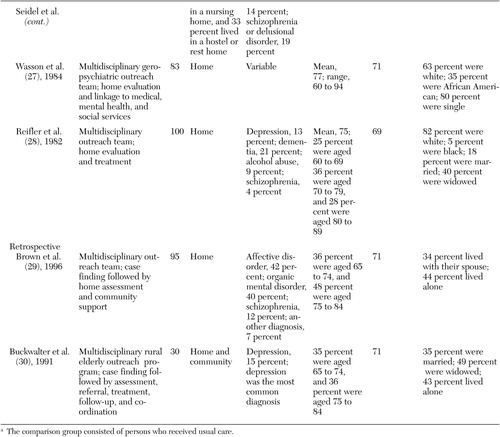

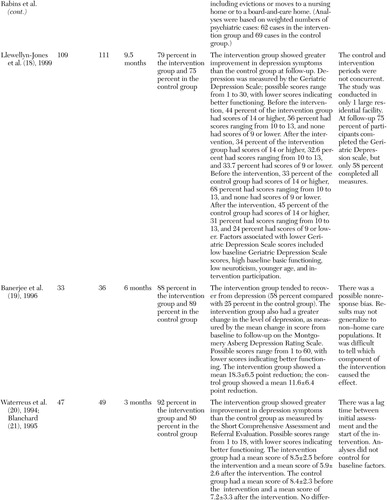

The effectiveness of outreach services in improving psychiatric symptoms and community tenure are reported in 12 studies, including five randomized controlled trials (16,17,18,19,20,21,22), one quasi-experimental study (23), and six uncontrolled cohort studies (25,26,27,28,29,30), as shown in Table 3. Older adults participating in these studies were predominantly female and tended to be between 75 and 85 years old. Three studies focused exclusively on older persons with depression, whereas the other nine studies included individuals with a range of diagnoses. All provided services in the older adults' place of residence.

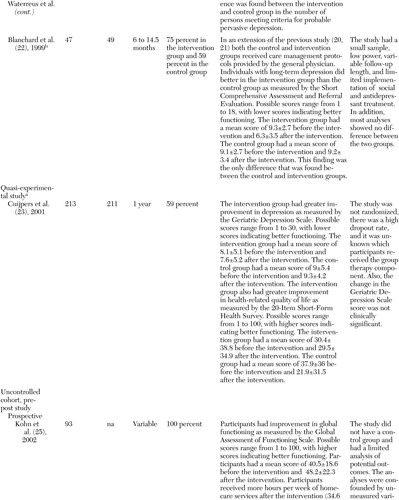

Four randomized controlled trials examined the effectiveness of implementing a care management protocol that was developed by a multidisciplinary team, although providers differed across studies. Rabins and colleagues (17) and Waterreus and colleagues (20) employed nurses, Banerjee and colleagues (19) employed a care manager, and Llewellyn-Jones and colleagues (18) employed physicians and residential staff to implement the intervention. The fifth randomized controlled trial evaluated the effectiveness of problem-solving therapy that was provided by social workers in senior public housing under the supervision of a psychiatrist (16). As shown in Table 4, relative to usual care, all interventions were associated with significant improvement in depressive symptoms. Of note, Rabins and colleagues (17) also found that outreach services were associated with a decrease in overall symptom severity, as measured by the total Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale score, for individuals with a variety of psychiatric disorders.

A recent quasi-experimental study evaluated a multifaceted education and support program that was administered in a residential care setting and compared the results with those of a usual care program (23) (Table 3). The target population included older persons who were incapable of living independently because of physical, psychiatric, or psychosocial constraints yet did not require extensive nursing home care. The intervention included training for caregivers and other employees of the residential home, informational meetings for residents and their relatives, and support groups and discussion and feedback sessions for care providers. As shown in Table 4, results indicated that an intervention that provides education, support, and feedback to residential care providers can reduce depressive symptoms and maintain health-related quality of life for older persons.

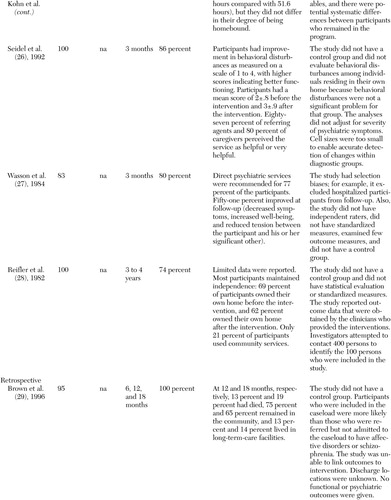

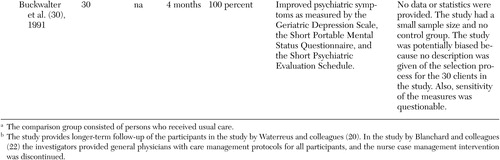

Findings from the small group of longitudinal cohort studies suggest that multidisciplinary outreach teams are associated with reduced psychiatric symptoms relative to baseline levels. These studies provided in-home assessment, followed by interventions that included either referral and linkage to outpatient treatment or to in-home psychiatric care. However, the specific interventions and outcomes differed, limiting cross-study comparisons or pooling of results. These multidisciplinary geriatric mental health outreach interventions were associated with improved global functioning (25), reduced psychiatric symptoms (27,30), and fewer behavioral disturbances (26) relative to baseline measurements of symptoms and functioning (Table 4). In addition, these interventions were associated with maintained independence (28,29) and were perceived as helpful to caregivers and referring agents (26).

Discussion

This systematic review of randomized controlled trials, uncontrolled cohort studies, and quasi-experimental outcome studies provides qualified support for the effectiveness of multidisciplinary psychogeriatric outreach services. Nonrandomized comparison studies of the gatekeeper model suggest that unconventional case finding approaches that are linked with referral to mental health providers may improve access for a group of older adults who are isolated and have a variety of diagnoses. Similarly, findings from a limited body of literature suggest that multidisciplinary care provided in an older person's home is effective in improving psychiatric outcomes. However, the data supporting these assertions are of variable quality. As such, any conclusions drawn should be tempered by the methodologic limitations of these data.

General conclusions drawn from pooled data in the form of meta-analyses or other cross-study evaluations are not possible because of the lack of comparability in study interventions, designs, and outcome measures. Our study found few randomized controlled trials, and in only one of the nine nonrandomized trials did the analysis adjust for severity of psychiatric symptoms (23). Furthermore, some studies reported outcome data that were obtained by the clinicians who provided the interventions. Among the 14 studies that we found, nine employed independent outcome raters (16,17,18,19,20,23,25,26,30), two documented interrater reliability (18,26), and seven used an intent-to-treat analysis (16,17,18,19,20,23,29). In general, uncontrolled cohort studies failed to qualify their conclusions by discussing the possibility that symptom improvement could represent regression to the mean. Finally, only two studies included information on the cost of the intervention (16,30), limiting the capacity of policy makers or providers to assess practical considerations associated with implementing and sustaining these treatment models in routine clinical settings.

Studies also varied with respect to case identification methods, type and intensity of treatment provided, composition of the treatment team, duration of follow-up, use of standardized measures, and participants' characteristics. Two of the 12 outcome studies used gatekeepers to make patient referrals (17,30), two used traditional referral mechanisms (25,28), and most screened participants from home and residential care settings or senior service agencies (16,18,20,21,23,27). Follow-up periods ranged from three months to three to four years. Outcomes varied across studies, and many studies failed to use standardized assessment measures (24,26,27,28,29,31). Finally, participants' characteristics also differed across studies. Although most studies had large proportions of female participants aged 70 to 80 years, ethnicity and diagnoses differed. Several studies targeted individuals with depression, whereas others included a range of diagnoses, most commonly depression and dementia. This variability complicates interpretation of the data and prohibits the calculation of an overall effect size. Moreover, variability in participants' characteristics may limit generalizability to younger male populations or to older individuals with psychotic, anxious, or other symptom constellations.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the evidence that supports geriatric mental health outreach service models using standardized inclusion and evaluation criteria. However, this review has several important limitations. First, the search strategy was limited to articles that were published in English. Second, the lack of a common taxonomy for characterizing types of mental health service models and associated outcome studies presents the possibility that this review failed to identify all relevant studies. Furthermore, this review process did not evaluate abstracts from scientific meetings, nor did it attempt to contact investigators in the field to identify unpublished studies. In addition, publication bias must be considered—studies with negative findings may not have reached dissemination venues. These factors may result in the underidentification of relevant evaluations of the outreach model and may have biased this review in favor of outreach services.

This systematic review applied a standardized approach to evaluating the effectiveness of face-to-face home and community-based mental health outreach interventions for older adults. It excluded outreach to institutional settings, which has been associated with improved clinical outcomes and lower use of acute services (34). It also excluded video-based outreach to rural areas. Although geriatric telepsychiatry shows promise for improving access to mental health care in underserved areas, literature on the application of this technology is limited to a small number of feasibility studies (35).

Our examination of the outreach literature was dominated by qualitative and observational outcome data (as evidenced by the 36 descriptive and four case study reports we found among the 58 studies that we reviewed). Although randomized controlled trials offer more support for a causal relationship, there is an inherent difficulty in executing and evaluating these trials in the field of mental health services. As such, the contribution from lower tiers of evidence should not be ignored, especially in an area with potential for improving access and quality of mental health care.

Conclusions

A diverse group of data-based studies support the use of outreach services in identifying isolated older adults and in improving the psychiatric symptoms of older persons. However, the preponderance of published literature in this area is anecdotal. Many of the published reports of outreach services suffer from methodologic limitations and potential difficulties with generalizability. Although some data provide evidence necessary for supporting national recommendations, much remains to be learned about the effectiveness of these services. Well-designed, controlled studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of outreach services with respect to case-finding techniques and generalizability of symptom reduction. Rigorous evaluation of outreach services is suggested across diverse populations and residential settings. Further research should employ manualized protocols in conjunction with the use of fidelity assessments and common outcome measures. Ultimately, outreach services may provide an essential bridge that connects effective pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions with individuals most in need of these interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elliott Fisher, M.D., M.P.H., Robin Larson, M.D., and Douglas Van Citters, M.S., for their comments.

Ms. Van Citters and Dr. Bartels are affiliated with the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center in Lebanon, New Hampshire. Dr. Bartels is also affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the Dartmouth Medical School. Send correspondence to Dr. Bartels at the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, 2 Whipple Place, Suite 202, Lebanon, New Hampshire 03766 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Description of studies that evaluated the effectiveness of referral models for identifying older adults in noninstitutional settings who are aged 65 and older and have mental illness

|

Table 2. Outcomes reported from studies that evaluated the effectiveness of referral models for identifying older adults in noninstitutional settings who are aged 65 and older and have mental illness

|

Table 3a. Description of studies that evaluated home and community-based treatment for older adults in noninstitutional settings who are aged 65 and older and have mental illness

|

Table 3b.

|

Table 4a. Outcomes reported from studies that evaluated home and community-based treatment for older adults in noninstitutional settings who are aged 65 and older and have mental illness

|

Table 4b.

|

Table 4c.

|

Table 4d.

|

Table 4e.

1. Projections of the Resident Population by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin:1999–2100. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, Population Projections Program, 2000Google Scholar

2. Jeste DV, Alexopoulos GS, Bartels SJ, et al: Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health: research agenda for the next 2 decades. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:848–853, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al: Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 survey's estimates. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:115–123, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar

5. Sheline YI: High prevalence of physical illness in a geriatric psychiatric inpatient population. General Hospital Psychiatry 12:396–400, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Unützer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, et al: Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. JAMA 277:1618–1623, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Rosenheck RA: Depressive symptoms and health costs in older medical patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:477–479, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Luber MP, Meyers BS, Williams-Russo PG, et al: Depression and service utilization in elderly primary care patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 9:169–176, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Unützer J, Simon G, Belin TR, et al: Care for depression in HMO patients aged 65 and older. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48:871–878, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bartels SJ, Clark RE, Peacock WJ, et al: Medicare and Medicaid costs for schizophrenia patients by age cohort compared with depression, dementia, and medically ill patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 11:648–657, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Bartels SJ, Dums AR, Oxman TE, et al: Evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care. Psychiatric Services 53:1419–1431, 2002Link, Google Scholar

12. Nordhus IH, Pallesen S: Psychological treatment of late-life anxiety: an empirical review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71:643–651, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Klap R, Tschantz K, Unützer J: Caring for mental disorders in the United States: a focus on older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 11:517–524, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Older Adults and Mental Health: Issues and Opportunities. Rockville, Md, Administration on Aging, 2001Google Scholar

15. Bartels SJ: Improving the United States' system of care for older adults with mental illness: findings and recommendations for the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 11:486–497, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Ciechanowski P, Wagner E, Schmaling K, et al: Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291:1569–1577, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Rabins PV, Black BS, Roca R, et al: Effectiveness of a nurse-based outreach program for identifying and treating psychiatric illness in the elderly. JAMA 283:2802–2809, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Llewellyn-Jones RH, Baikie KA, Smithers H, et al: Multifaceted shared care intervention for late life depression in residential care: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 319:676–682, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Banerjee S, Shamash K, Macdonald AJ, et al: Randomised controlled trial of effect of intervention by psychogeriatric team on depression in frail elderly people at home. British Medical Journal 313:1058–1061, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Waterreus A, Blanchard M, Mann A: Community psychiatric nurses for the elderly: well tolerated, few side-effects and effective in the treatment of depression. Journal of Clinical Nursing 3:299–306, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Blanchard MR, Waterreus A, Mann AH: The effect of primary care nurse intervention upon older people screened as depressed. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 10:289–298, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Blanchard MR, Waterreus A, Mann AH: Can a brief intervention have a longer-term benefit? The case of the research nurse and depressed older people in the community. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 14:733–738, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Cuijpers P, van Lammeren P: Secondary prevention of depressive symptoms in elderly inhabitants of residential homes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 16:702–708, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Florio ER, Jensen JE, Hendryx M, et al: One-year outcomes of older adults referred for aging and mental health services by community gatekeepers. Journal of Case Management 7:74–83, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

25. Kohn R, Goldsmith E, Sedgwick TW: Treatment of homebound mentally ill elderly patients: the multidisciplinary psychiatric mobile team. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 10:469–475, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Seidel G, Smith C, Hafner RJ, et al: A psychogeriatric community outreach service: description and evaluation. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 7:347–350, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Wasson W, Ripeckyj A, Lazarus LW, et al: Home evaluation of psychiatrically impaired elderly: process and outcome. Gerontologist 24:238–242, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Reifler BV, Kethley A, O'Neill P, et al: Five-year experience of a community outreach program for the elderly. American Journal of Psychiatry 139:220–223, 1982Link, Google Scholar

29. Brown P, Challis D, vonAbendorff R: The work of a community mental health team for the elderly: referrals, caseloads, contact history, and outcomes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 11:29–39, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Buckwalter KC, Smith M, Zevenbergen P, et al: Mental health services of the rural elderly outreach program. Gerontologist 31:408–412, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Florio ER, Raschko R: The gatekeeper model: implications for social policy. Journal of Aging and Social Policy 10:37–55, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Florio ER, Rockwood TH, Hendryx MS, et al: A model gatekeeper program to find the at-risk elderly. Journal of Case Management 5:106–114, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

33. Raschko R: The Spokane Elder Care Program: community outreach methods and results, in Progress in Alzheimer's Disease and Similar Conditions. American Psychopathological Association series. Edited by Heston LL. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1997Google Scholar

34. Bartels SJ, Moak GS, Dums AR: Models of mental health services in nursing homes: a review of the literature. Psychiatric Services 53:1390–1396, 2002Link, Google Scholar

35. Jones BN, Ruskin PE: Telemedicine and geriatric psychiatry: directions for future research and policy. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 14:59–62, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar