Factors Associated With High Use of Public Mental Health Services by Persons With Borderline Personality Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The research presented here was a pilot study to identify clinical factors associated with high use (as opposed to lower use) of inpatient psychiatric services by persons with borderline personality disorder. METHODS: The initial sample was a random sample of English- and Spanish-speaking persons aged 18 to 60 years who had received at least one outpatient mental health service in the previous 90-day period and were enrolled in one of the participating mental health centers in King County, Washington. A random sample of persons who met selection criteria was randomly drawn; persons with high levels of use were oversampled to ensure adequate representation. Twenty-nine participants met full criteria for borderline personality disorder on the Personality Disorders Examination structured interview and completed all measures. Fifteen (52 percent) of these had a high level of use of inpatient services, and 14 did not. RESULTS: High use of inpatient psychiatric services was predicted by a history of parasuicide in the previous two years but not by the number or severity of parasuicides; by the presence and number of anxiety disorders but not by depression or psychotic or substance use disorders; and by poorer cognitive functioning. Life stressors, global functioning, and health service variables did not differentiate patients with high levels of service use from other patients with borderline personality disorder. CONCLUSIONS: Further research should explore these predictors of service use to determine whether they are replicated in larger samples, and treatments that target these variables should be evaluated.

In this period of concern about rising health care costs and restrictions in public funding, patient populations that use large quantities of public resources are of particular interest. One such population in the public mental health system is patients with mental illness who use large amounts of inpatient psychiatric services.

Studies have shown that between 9 percent and 40 percent of these high-level users of services have received a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (1,2,3,4,5). The highest percentages were in studies that focused specifically on persons with the greatest use of psychiatric hospitals (1,5). The significance of these numbers is magnified by the severity and chronicity of borderline personality disorder (6,7,8). Short-term longitudinal studies have found little change in functional level and consistent high rates of psychiatric hospitalization over periods of two to five years (9,10,11).

In one study, a majority (64 percent) of patients with borderline personality disorder who were followed up for three years after an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization were unable to work (12). Almost a third of the patients in that study were referred to public services on discharge (12). Bender and colleagues (13) found that among persons with borderline personality disorder who sought treatment in a research trial, 95 percent had received individual therapy; 56 percent, group therapy; 42 percent, family or couples therapy; 37 percent, day treatment; and 72 percent, psychiatric hospitalization. These patients were also significantly more likely than control group patients with depression to have used each of these services.

Swigar and colleagues (3) and Rascati (14) noted that public mental health outpatient services focus mostly on the needs of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and do not meet the needs of patients with borderline personality disorder or prevent rehospitalization. Both Karterud and colleagues (15) and Kofoed and colleagues (16) noted that persons with borderline personality disorder quickly dropped out of their programs (day treatment and dual diagnosis programming, respectively). Weisbrod (17) found that assertive community treatment, when provided to persons with personality disorders, cost more than a hospital-based control treatment, in contrast with the cost savings associated with provision of assertive community treatment to patients with schizophrenia and other psychoses. In addition, assertive community treatment did not demonstrate the modest effects on earnings and clinical ratings that were found for these other diagnoses.

Recently, however, randomized controlled studies evaluating two intensive outpatient treatments have found significant effects on the symptoms of borderline personality disorder (18,19,20,21,22,23). Only Linehan's dialectical behavior therapy is currently available in public mental health systems (24,25) and has been evaluated for effectiveness in public systems (26,27,28,29,30).

In addition to expanding treatment that is generally effective for borderline personality disorder, another means of improving services for this population is to identify factors associated with a high hospitalization rate among persons with borderline personality disorder. Treatments developed to address these factors specifically could then be evaluated for effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Reducing hospitalization through improvements in outpatient services or patient functioning would not only reduce costs but also benefit the individuals who have borderline personality disorder.

The research presented here was a population-based pilot study to identify clinical factors associated with high use, as opposed to lower use, of inpatient psychiatric services by persons with borderline personality disorder. On the basis of clinical experience and empirical investigation, we proposed several hypotheses. We hypothesized that clients with borderline personality disorder who had high levels of service use would engage in more—and more severe—suicidal behavior compared with other public mental health clients with borderline personality disorder. We also hypothesized that these clients with high levels of use would have a greater burden of comorbid illness as indicated by more frequent diagnosis of psychotic disorders, depressive disorders, and substance use disorders and that these clients would be more often cognitively impaired, experience more life stressors, be rated as having poorer functioning by their outpatient case manager, receive more frequent and intense outpatient psychiatric services, and be less satisfied with their outpatient psychiatric services or more satisfied with inpatient psychiatric services.

Methods

Sample and sampling procedure

The study's initial sample was a random sample of English- and Spanish-speaking persons aged 18 to 60 years who had received at least one outpatient mental health service in the previous 90 days and were enrolled in one of the participating mental health centers in the King County Regional Support Network (KCRSN). KCRSN administers publicly funded mental health services for a total of 17 mental health centers in King County, Washington. These services are provided primarily to patients with severe and persistent mental illness who are receiving public assistance. Fifteen agencies agreed to participate in the study, representing 91 percent of KCRSN's clients. The study was conducted from April 1996 to April 1999.

Individuals who met inclusion criteria were randomly selected from KCRSN's management information system. Persons with high levels of use were oversampled to ensure adequate representation. High users of inpatient mental health services were defined as those with at least three inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations in the previous two years or any hospitalization of at least 30 days in the previous two years. All high service users were included in the selection sample.

To protect the privacy of KCRSN's clients, each participating agency was sent the list of the clients who had been randomly selected from that agency by KCRSN's management information system. Each agency then sent an invitation from the study to each potential participant, under its own cover letter, which endorsed the study. Recruitment was initially conducted by asking potential participants to return a postcard in which they agreed to participate. This actively oriented recruitment approach yielded a low response rate and thus was later changed to the more passively oriented approach of targeting clients who did not call the agencies to refuse participation. The agencies provided the research staff with lists of the clients who did not call to refuse, along with their contact information.

The agencies provided correct contact information for 481 individuals, 18 of whom could not be reached. The remaining 463 individuals were contacted and asked to complete a screening interview. Of those contacted, 174 (38 percent) refused to participate, either on the telephone or at the screening interview. Thus 289 individuals completed the screening interview.

Representativeness of the screening sample was examined by gender and ethnicity. The screening sample of 289 was approximately half female (158 individuals, or 55 percent). A majority of the sample was Caucasian (240 individuals, or 83 percent), with the remainder African American (31 persons, or 11 percent), Latino (seven persons, or 2 percent), Native American or Alaskan Native (five persons, or 2 percent), Asian (four persons, or 1 percent), or Middle Eastern or Pacific Islander (one person in each category). Except for a higher proportion of Asian patients, the initial random sample drawn from the 15 participating agencies by KCRSN was comparable: 52 percent female; 75 percent Caucasian; 13 percent African American, 4 percent Latino, 4 percent Asian, Middle Eastern, or Pacific Islander; 2 percent Native American or Alaskan Native; and 2 percent of mixed ethnicity. Thus, with the exception that many Asian clients could not speak English sufficiently to participate in the study, the study sample was highly representative of the underlying population.

Screening criteria were positive scores on at least three items of the borderline personality disorder section of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire—Revised. Of the patients who completed screening interviews, 206 (71 percent) met these criteria, of whom 156 (76 percent) scheduled and completed the diagnostic assessment—the Personality Disorders Examination (PDE) for borderline personality disorder. Definite diagnosis on the PDE, as in DSM-IV, was defined as a positive score on five out of nine criteria.

Instruments

Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire—Revised. The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire—Revised (PDQ-R), a brief questionnaire containing items representing criteria for all DSM-III-R personality disorders, was used for an initial screening of the study participants for borderline personality disorder. This instrument has excellent reliability and validity as a screening measure (31,32,33,34), although it produces a high false-positive rate.

Personality Disorders Examination. The borderline personality disorder items of the PDE were administered to determine whether participants met the criteria for a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (35). The PDE is the standard for the assessment of personality disorders used by the World Health Organization. Interrater reliability for borderline personality disorder on the PDE has been found to range from .73 to .89 and temporal stability to range from .56 to .84, clearly in the acceptable region (35,36).

Parasuicide History Interview. The Parasuicide History Interview (PHI) was developed and revised by Linehan and colleagues (unpublished manuscript, 1994) to evaluate the frequency, severity, and medical lethality of acts of intentional self-injury over a specific period. This measure has been used in studies evaluating the outcome of treatment for parasuicidal persons with borderline personality disorder (20,21,37).

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) was used to determine whether participants met the criteria for DSM-IV axis I mental disorders (38). Psychometric studies have shown excellent interrater reliability and validity of the SCID as a diagnostic measure (39,40,41).

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT), a brief measure of verbal intelligence, was used to identify cognitive impairment (42). The test produces an IQ score comparable to those of other intelligence tests, such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised (WAIS-R) and the Stanford-Binet test (43,44,45).

Life Experiences Survey. The Life Experiences Survey (LES) is a 47-item self-report measure that assesses both positive and negative life experiences as well as individualized ratings of the impact of the events (46). Summary scores of intensity ratings are made for all events rated positive, all events rated negative, and all events in total.

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ), an eight-item measure, was used to assess clients' satisfaction with the outpatient mental health services they received (47,48,49). In this study, the CSQ was also modified to assess satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric services, because we hypothesized that such satisfaction might explain overuse of those services. Internal consistency (alpha) for this revised measure was .99.

KCRSN's management information system database

KCRSN's management information system database contains clinical and treatment information for all publicly funded mental health clients in King County. This database is designed for administrative reporting and includes clinical ratings and service use. For this study we used the case managers' Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores and data on outpatient service use. Outpatient service use was computed as the total number of minutes of service as well as "standardized service hours," whereby the county assigns higher weights to higher-intensity services, such as individual appointments (1:1) and medical appointments (1.5:1), than to lower-intensity services, such as group services (1:6) and day treatment services (1:12).

Procedures

Participants were screened for borderline personality disorder by research staff—a master's-level clinician and undergraduate psychology students supervised by this clinician and the principal investigator. All structured interviews were conducted by the first author or the master's-level clinician, who were both trained on the PDE by its author, Armand Loranger, and on the SCID by a psychiatrist specializing in administration of the SCID. The principal investigator and the master's-level clinician had shown excellent interrater reliability previously on both PDE and SCID diagnoses.

Between one and three interviews were conducted with each participant, depending on the participants' wishes and staff time available. Individuals were paid $5 at the screening interview, $15 for PDE assessment (if they passed the screening), and $20 for the remainder of the assessment (if they met the criteria for borderline personality disorder). All contact, consent, and interview procedures were approved by university and county institutional review boards.

Data analysis

We used t tests, without equal variances assumed, to compare the high-level and lower-level service users with borderline personality disorders on continuous measures. Because of the small samples, Fisher's exact tests were used to compare 2 × 2 categorical variables. In cases of nonnormal distributions, Kruskal-Wallis tests were used. A liberal alpha of .05 was used for these analyses given the exploratory nature of this pilot study.

Results

Thirty-three participants met the full criteria for borderline personality disorder on the PDE structured interview. Of these, 29 completed all subsequent measures and constituted the final sample. Fifteen of these 29 persons with borderline personality disorder (52 percent) had a high level of use of inpatient services, and 14 had a lower level of use. This final sample was approximately three-quarters female (22 patients, or 76 percent). A majority of the sample was Caucasian (24 patients, or 83 percent), and the remainder were African American (five patients, or 17 percent). These proportions are comparable to those in other samples of persons with borderline personality disorder.

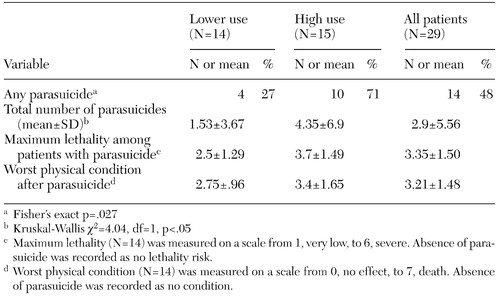

No significant differences were found between the patients who had a high level of service use and those with lower use in terms of gender or ethnicity. As expected, the presence of any parasuicide in the previous two years was more common among participants with high levels of service use (χ2=4.16, df=1, p<.05), and a Kruskal-Wallis test of the number of parasuicides in the previous two years demonstrated a significant difference between the two groups (Table 1). However, no significant differences between groups were found in the maximum lethality or worst physical condition associated with any parasuicide in the previous two years.

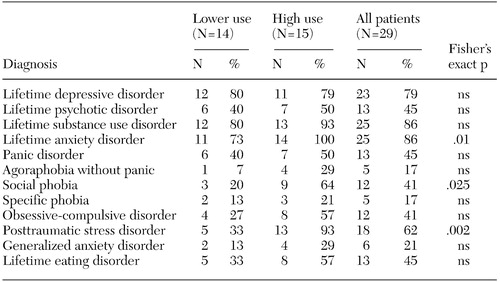

As can be seen in Table 2, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in the frequency of comorbid axis I disorders for the three major disorders. However, post hoc analyses showed a significant difference in lifetime diagnosis of an anxiety disorder (Fisher's exact p=.10)—all high users met the criteria for an anxiety disorder. The number of lifetime anxiety disorder diagnoses also differed between groups (t=−4.05, df=26, p<.001). High users had an average of 3.2 anxiety disorders, compared with 1.4 in the group of patients with lower levels of service use. As can be seen in Table 2, rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) differed between the two groups (Fisher's exact p=.002), as did the rate of social phobia (χ2=5.86, df=1, p<.05). Post hoc analyses did not indicate a significant difference in rates of lifetime eating disorders.

As expected, a comparison of PPVT-R scores between groups demonstrated lower cognitive functioning among patients with high levels of service use (t=2.17, df=16, p<.05). The mean±SD IQ score for high users was 89±36 and for lower-level users was 114±22, representing IQ in the normative range. No significant differences were noted in the percentage of patients in each group with an IQ below 80—that is, indicative of cognitive impairment. (Note that PPVT-R scores were missing for seven participants.)

Contrary to expectation, positive LES scores, negative LES scores, and total LES scores did not differ significantly between groups. Similarly, case managers' GAF ratings did not differ significantly between groups.

Finally, we found no between-group differences in service use or satisfaction. No significant differences were found in the total number of services received, the number of standardized service hours (a measure used by the county to evaluate service intensity), satisfaction with outpatient services, or satisfaction with inpatient services.

Discussion and conclusions

In this community mental health outpatient sample in King County, Washington, high levels of use of inpatient psychiatric services among persons with borderline personality disorder were predicted by a history of parasuicide in the previous two years but not by the number or severity of parasuicides. High levels of use were also predicted by the presence and number of anxiety disorders but not by the presence of depression, psychotic disorders, or substance use disorders, and were predicted by poorer cognitive functioning. Other diagnoses were prevalent but did not differ significantly between patients with borderline personality disorder who used high levels of services from other patients with borderline personality disorder. Life stressors, global functioning, and health service variables also did not differentiate groups.

As expected, both the presence and the number of parasuicides were associated with high levels of service use. These results support the implementation of treatments for borderline personality disorder as used by Linehan and colleagues (20,21,22) and by Bateman and Fonagy (18,19), both of which showed reductions in parasuicide and hospitalizations. Although neither approach is known to effectively treat anxiety disorders, Linehan's dialectical behavioral therapy shares many strategies with empirically suggested treatments for anxiety including PTSD and social phobia.

A higher rate of anxiety disorders among the high-level service users was the major diagnostic finding of this study. Other studies have shown that anxiety is an important risk factor for suicide attempts among patients with depression, although no difference was observed between the two groups in the frequency of panic disorder, which is the anxiety diagnosis most strongly associated with suicide. It is possible that the higher rate of social phobia contributed to problems with treatment engagement. Similarly, the avoidance of and nonparticipation in treatment observed among patients with PTSD—the frequency of which was also higher among these high-level users of services—could have played some role in our findings.

The patients with borderline personality disorder who had a high level of service use had poorer cognitive functioning than the other patients with borderline personality disorder but were generally not impaired in general cognitive functioning. This result is not likely to be explained by dyslexia or other learning disabilities, because the PPVT does not require reading and is considered insensitive to learning disability. It may be that lower scores reflect general deficits in the home environment or problems in school that result in underdevelopment of verbal ability. If this is the case, treatments for patients with borderline personality disorder who have high levels of service use may need to target life skills and vocational issues very specifically to ensure that patients understand and effectively complete the steps toward normative work, housing, and financial functioning that are incompatible with hospitalization. The lower cognitive functioning among these patients also suggests slow pacing needs to be used in auxiliary psychotherapy with patients who have borderline personality disorder to ensure comprehension and application.

This study had important limitations. The sample was small, and many potential participants were eliminated either because we were unable to contact them or because they refused to participate. However, the sample was representative in terms of gender and ethnicity and was selected randomly from a general public-sector mental health system. In contrast, most previous studies of persons with the greatest use of services during inpatient hospitalization have focused on select treatment-seeking samples at a time of acute crisis. Although only a pilot study, ours is the first study to compare patients with borderline personality disorder who overuse hospitalization with those who do not. Replication of these results with larger populations is critical, especially with regard to the unexpected differences in rates of anxiety diagnoses. Such research will allow for cost savings in the ideal way, because patients improve their functioning and their lives.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 1R03-Mh-55587-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors acknowledge the effort and patience of Evelyn Mercier and Eileen Magill in collecting and organizing the data for this project.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the University of Washington, Box 359911, Seattle, Washington 98195 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Suicidal behavior in the previous two years among persons with borderline personality disorder with high and lower levels of service use

|

Table 2. DSM diagnoses among persons with borderline personality disorder with high or lower levels of service use

1. Geller JL: In again, out again: preliminary evaluation of a state hospital's worst recidivists. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 4:386–390, 1986Google Scholar

2. Surber RW, Winkler EL, Monteleone M, et al: Characteristics of high users of acute psychiatric inpatient services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:1112–1114, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Swigar ME, Astrachan B, Levine MA, et al: Single and repeated admissions to a mental health center: demographic, clinical, and use of service characteristics. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 37:259–266, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Widiger TA, Weissman MM: Epidemiology of borderline personality disorder. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1015–1021, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Woogh CM: A cohort through the revolving door. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 31:214–221, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

6. McGlashan TH: The Chestnut Lodge Followup Study: III. long-term outcome of borderline personalities. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:20–30, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Mehlum L, Friis S, Irion T, et al: Personality disorders 2–5 years after treatment: a prospective follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 84:72–77, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Lehman AF, Myers CP, Thompson JW, et al: Implications of mental and substance use disorders: a comparison of single and dual diagnosis patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:365–370, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Barasch A, Frances A, Hurt S, et al: Stability and distinctness of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 142:1484–1486, 1985Link, Google Scholar

10. Dahl AA: Prognosis of the borderline disorders. Psychopathology 19:68–79, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Mehlum L, Friis S, Vaglum P, et al: The longitudinal pattern of suicidal behaviour in borderline personality disorder: a prospective follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 90:124–130, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Antikainen R, Hintikka J, Lehtonen J, et al: A prospective three-year follow-up study of borderline personality disorder inpatients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 92:327–335, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al: Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:295–302, 2001Link, Google Scholar

14. Rascati JN: Managed care and the discharge dilemma. Psychiatry 53:124–126, 1990Google Scholar

15. Karterud S, Vaglum S, Friis S, et al: Day hospital therapeutic community treatment for patients with personality disorders: an empirical evaluation of the containment function. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:238–243, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kofoed L, Kania J, Walsh T, et al: Outpatient treatment of patients with substance abuse and co-existing psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:867–872, 1986Link, Google Scholar

17. Weisbrod BA: A guide to benefit-cost analysis, as seen through a controlled experiment in treating the mentally ill. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law 7:808–845, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1563–1569, 1999Link, Google Scholar

19. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization: an 18-month follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:36–42, 2001Link, Google Scholar

20. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, et al: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:1060–1064, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Linehan MM, Tutek DA, Heard HL, et al: Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1771–1776, 1994Link, Google Scholar

22. Linehan MM: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

23. Linehan MM: Combining pharmacotherapy with psychotherapy for substance abusers with borderline personality disorder: strategies for enhancing compliance. NIDA Research Monograph 150. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1995Google Scholar

24. Hawkins KA, Sinha R: Can line clinicians master the conceptual complexities of dialectical behavior therapy? An evaluation of a state department of mental health training program. Journal of Psychiatric Research 32:379–384, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Simpson EB, Pisotrello J, Begin A, et al: Use of dialectical behavior therapy in a partial hospital program for women with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Services 49:669–673, 1998Link, Google Scholar

26. Koons CR, Robins CJ, Tweed JL, et al: Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy, in pressGoogle Scholar

27. Van den Bosch LM, Schippers VR, van den Brink W: Dialectical behavior therapy of borderline patients with and without substance use problems: implementation and long-term effects. Addictive Behaviors 27:911–923, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Turner RM: Naturalistic evaluation of dialectical behavior therapy-oriented treatment for borderline personality disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 7:413–419, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Rathus JH, Miller Al: Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 32:146–157Google Scholar

30. Elwood L, Comtois KA, Holdcraft LC, et al: Effectiveness of DBT in a community mental health center. Presented at annual convention of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Reno, Nev, Nov 2002Google Scholar

31. Hyler SE, Skodol AE, Kellman HD, et al: Validity of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-Revised: comparison with two structured interviews. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:1043–1048, 1990Link, Google Scholar

32. Trull TJ: Temporal stability and validity of two personality disorder inventories. Psychological Assessment 5:11–18, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Trull TJ, Larson SL: External validity of two personality disorder inventories. Journal of Personality Disorders 8:96–103, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Yeung AS, Lyons MJ, Waternaux CM, et al: Empirical determination of thresholds for case identification: validation of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire—Revised. Comprehensive Psychiatry 34:384–391, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, et al: The International Personality Disorder Examination. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:215–224, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Zimmerman M: Diagnosing personality disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:225–245, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE: Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:971–974, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II): II. multi-site test-retest reliability study. Journal of Personality Disorders 9:92–104, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Segal D, Hersen M, Van Hasselt V: Reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R: an evaluation review. Comprehensive Psychiatry 35:316–327, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Ventura J, Liberman R, Green M: Training and quality assurance with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P). Psychiatric Research 79:163–173, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Zanarini MC: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders 14:291–299Google Scholar

42. Dunn L, Dunn L: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised. Circle Pines, Minn, American Guidance Service, 1981Google Scholar

43. Altepeter TS, Johnson KA: Use of the PPVT-R for intellectual screening with adults: a caution. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 7:39–45, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

44. Ernhardt C: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test: automated application in a statewide psychiatric system. Psychiatric Quarterly Supplement 42:317–330, 1968Google Scholar

45. Mangiaracina J, Simon MJ: Comparison of the PPVT-R and WAIS-R in state hospital psychiatric patients. Journal of Clinical Psychology 42:817–820, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM: Assessing the impact of life changes: development of the Life Experiences Survey. Journal of Clinical Psychology 46:932–946, 1978Google Scholar

47. Attkisson CC, Zwick R: The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire: psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning 5:233–237, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Gaston L, Sabourin S: Client satisfaction and social desirability in psychotherapy. Evaluation and Program Planning 15:227–231, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

49. Nguyen T, Attkisson C, Stegner B: Assessment of patient satisfaction: development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Evaluation and Program Planning 6:299–314, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar