Perceptions of Discrimination Among Persons With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: The authors sought to gain further perspective on discrimination experienced by persons with mental illness by comparing self-reports of discrimination due to mental illness to self-reports of discrimination due to other group characteristics, such as race, gender, and sexual orientation. METHODS: A total of 1,824 persons with serious mental illness who participated in a baseline interview for a multistate study on consumer-operated services completed a two-part discrimination questionnaire. The first part of the questionnaire assessed participants' perceptions about discrimination due to mental illness as well as more than half a dozen other group characteristics. The second part of the questionnaire asked participants who reported some experience with discrimination to identify areas in which this discrimination occurred, such as employment, education, and housing. RESULTS: More than half of the study participants (949 participants, or 53 percent) reported some experience with discrimination. The most frequent sources of this discrimination were mental disability, race, sexual orientation, and physical disability. Areas in which discrimination frequently occurred included employment, housing, and interactions with law enforcement. Areas in which discrimination was experienced did not significantly differ among groups of study participants characterized by mental disability, race, gender, sexual orientation, or physical disability. CONCLUSIONS: Discrimination based on group characteristics other than mental illness does not diminish the impact of stigma associated with mental illness. Antistigma programs need to target not only discrimination related to mental illness but also that associated with other group characteristics, such as race, gender, sexual orientation, and physical disability.

The U.S. Surgeon General, in his 1999 report on mental health (1), identified stigma as a key barrier not only to adequate treatment but also to the breadth of life opportunities for people with mental illness. The White House echoed that concern in the same year with its conference on mental illness, during which Tipper Gore made stigma a key target for social change. Amid these important advocacy efforts have been several studies describing stigma and testing explanatory models (2,3,4,5,6,7,8).

Key to this body of research have been first-person studies—that is, obtaining the perspective of people who have been labeled as mentally ill about their experiences with stigma. Surveys and qualitative interviews with persons who have mental illness have yielded several findings. The results suggest that a majority of these persons perceive themselves as being stigmatized by others (9,10,11), expect to be treated poorly by the public because of this stigma (11,12,13,14), and suffer demoralization and low self-esteem due to internalization of the stigma (12,15,16,17,18).

The body of research in this area has been criticized as being limited in geographic scope or representing general impressions of stigma rather than specific experiences. Wahl (19) sought to rectify these limitations through a nationwide study focusing on the individual's experience with discrimination. A total of 1,301 persons with mental illness from across the United States, solicited through the newsletter of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) and by members of NAMI's consumer council, completed questionnaires about their experience with stigma and discrimination. What is remarkable about Wahl's findings, as in many of the studies of this sort, is that almost 80 percent of the sample reported direct experience with stigma—for example, they "had overheard people making offensive comments about mental illness." Moreover, 70 percent of the sample had been treated as less competent by others once their illness was known.

In the study reported here, we sought to expand on Wahl's findings by trying to put some perspective on the problem of discrimination; namely, how does the discrimination due to mental illness compare with discrimination that results from being a part of other stigmatized groups? People with mental illness are often members of a disenfranchised class that comprises a variety of other stigmatized outgroups, including people of color and those who are impoverished. Moreover, many people identify with multiple groups that are publicly stigmatized (20). In this study we wanted to answer the question of how the stigma related to mental illness compares with stigma related to being black, female, poor, or gay. A consumer at one of our programs stated the point succinctly: "If you think being mentally ill is bad, try also being poor and black!"

The study had two goals. First, we compared the proportion of persons with mental illness who reported discrimination with the proportion of persons from the same sample who also happened to be black, female, gay, or physically disabled. We expected that people with a mental illness, as a group, would experience discrimination for multiple reasons, not just their mental illness. Second, we examined some of the domains in which people might experience discrimination, including employment, education, housing, law enforcement, and mental health services. This second aspect of the study also involved examining the proportion of persons with mental illness who reported discrimination in each domain compared with the proportion who reported discrimination due to race, gender, or some other characteristic.

Methods

Data for this analysis were obtained during baseline assessment of participants in the consumer-operated services project, which was conducted from March 1999 to August 2002 (manuscript in preparation, Campbell J, Johnsen M, Blyler C, et al). The protocol for this larger study received approval by the institutional review boards of all the institutions participating in the study. Eligible persons were fully informed and then consented to participate before beginning the study. This multisite study (in California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Maine, Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee) was funded by the Center for Mental Health Services and examined the impact of consumer-operated services on persons with serious mental illness. Inclusion criteria were a DSM-IV axis I diagnosis consistent with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression, as well as a significant functional disability due to mental illness. Proxies for significant functional disability included receipt of Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and at least two state hospitalizations.

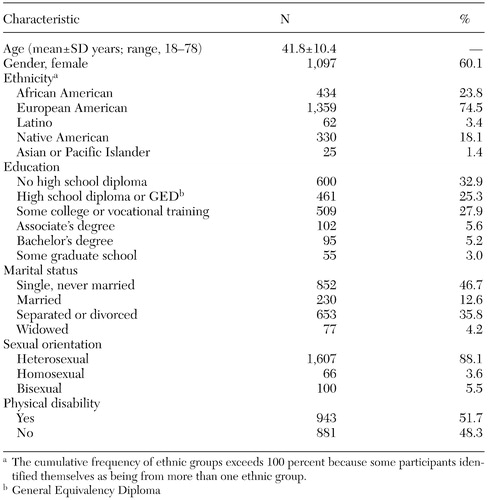

Patients were recruited from community mental health centers in each of the participating states and were randomly assigned to receive traditional mental health services or traditional services plus consumer-operated programs. A total of 1,824 individuals completed baseline analyses and provided useable data. Demographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1.

Discrimination Questionnaire

Twenty-six interview-based measures were administered to the study participants before they entered the study. Data reported in this article are based on responses to the Discrimination Questionnaire (DQ), which was one of several measures of social inclusion, a core concept in our study's logic model. The DQ is an adaptation of the Schedule of Racist Events (SRE) (21). Previous research on the SRE has demonstrated that it has high internal consistency (alpha>.94), test-retest reliability over a one-month interval (r>.94), and construct validity (22,23).

Modifications to the SRE included changing the focus of the measure to examine multiple sources of discrimination beyond race and to use global questions rather than the behaviorally specific items found in the SRE. The Experience of Discrimination Questionnaire (24) provided the structure for assessing types of discrimination reported on the DQ. Responses to the DQ divided the sample into two groups on the basis of the yes-or-no question, "Do you believe you have been discriminated against, for instance, because of your mental disability, race, gender, sexual orientation, economic circumstance, or some other reason?" Participants who answered "yes" to this question were then asked yes-or-no questions about whether they believed they had been discriminated against as a result of 12 specific conditions, including mental and physical disability, race, gender, and sexual orientation. These participants were then asked whether discrimination occurred in the context of seven specific situations, including employment, education, and housing.

Results

Perceived sources of discrimination

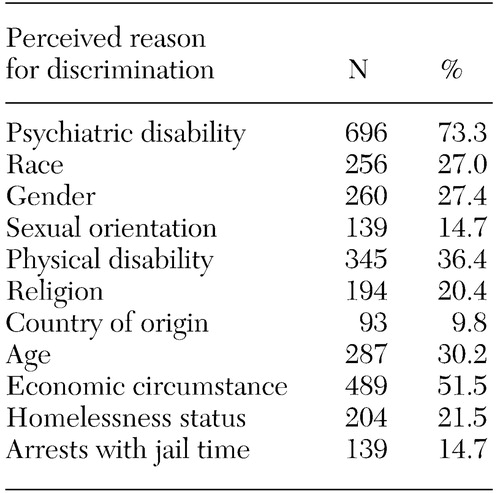

The frequency of endorsement of individual experiences with discrimination is summarized in Table 2. A total of 949 participants (52.4 percent) believed that they had been discriminated against on the basis of their belonging to some outgroup. Subsequent analyses examined whether this discrimination was due to a variety of individual characteristics.

The most common reason for discrimination cited was mental disability. Among the participants who reported that they had experienced discrimination, 696 (73.3 percent) reported that the prejudice was due, at least in part, to their mental disability. Thus only 37.7 percent of the entire sample reported a concern about discrimination related to their psychiatric disability, which is much lower than the 70 percent reported by Wahl (19).

One way to make further sense of this finding is to compare the proportion of participants who acknowledged discrimination due to mental illness with the proportion reporting discrimination that might be due to other characteristics, such as race, gender, sexual orientation, and physical disability. As can be seen in the table, the next most frequent source of discrimination was economic circumstance—poverty was frequently a cause of discrimination. About a third of the sample reported discrimination because of physical disability—including both problems with ambulation and sensory disabilities—and older age. About a quarter of the sample reported discrimination due to gender and to race, and about a fifth reported stigma due to their religion and to being homeless.

At first glance, it seems that discrimination due to mental illness was far more frequent than discrimination due to any of these other group characteristics: 73.3 percent compared with 51.5 percent for economic circumstance, the next most frequent category. However, note that we posed the question about discrimination due to mental disability in a sample that was 100 percent self-identified as psychiatrically disabled. To permit a more accurate comparison between groups experiencing discrimination on the basis of mental disability and other groups, we examined the frequencies of discrimination reported by the various subgroups participating in the study.

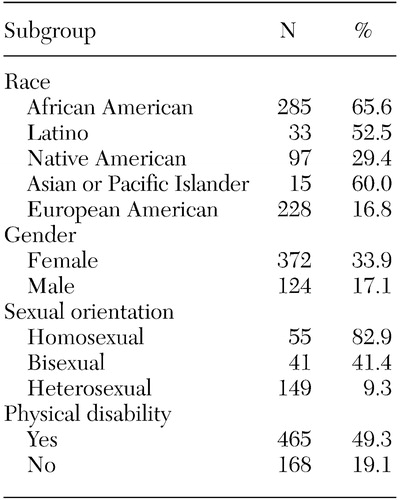

Table 3 summarizes the frequency of discrimination due to race, gender, sexual orientation, and physical disability in corresponding subgroups—for example, the proportion of black individuals who reported racial discrimination. This analysis revealed significantly higher rates of discrimination per category. Although 260 (27.4 percent) of the 949 participants who experienced discrimination reported racial discrimination, 65.6 percent of the black participants, 52.5 percent of the Latino participants, and 60 percent of the Asian participants reported experiencing this kind of discrimination. When we examined the other categories in the same way, 33.9 percent of women, 82.9 percent of gay men and lesbians, and 49.3 percent of persons with physical disabilities reported discrimination.

An additional question is that of how reporting discrimination associated with mental illness interacts with discrimination associated with other group identities. For example, are people who have experienced the stigma of being in another outgroup—for example, African Americans or women—more likely to report discrimination due to stigma? To answer questions like these, we conducted a cross-tabulation that contrasted the cells for discrimination due to mental illness discrimination—that is, responses to the yes-or-no question "Do you believe you have been discriminated against because of mental illness?"—with other outgroup identities, such as responses to "Were you discriminated against because you are African American?"

We used European-American males as the reference group and compared the frequency of stigmatization due to mental illness in that group with the frequency in the various outgroups. The results were interesting: women, persons from ethnic minorities, persons with physical disabilities, and gay and lesbian participants reported discrimination due to mental illness at rates similar to those among European-American males. All rates fell within a range of 65 percent to 75 percent, and all chi square comparisons were nonsignificant (p>.10). Thus these results do not support the notion that being a member of an additional stigmatized group will increase the likelihood of a person's viewing his or her mental illness as the source of discrimination.

Areas in which discrimination occurs

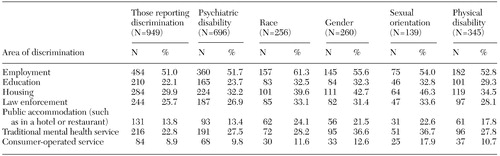

A second interesting question examined in this analysis was the question of the areas in which discrimination occurred among the participants who reported any kind of discrimination. The findings are summarized in Table 4. The area in which discrimination was most frequent was employment: 484 (51 percent) of the participants who experienced discrimination reported that they experienced discrimination in this area. About a third of the subsample reported discrimination in the area of housing, about a quarter in interactions with law enforcement agencies, and about a fifth in education settings.

We were also concerned about experiences with discrimination in obtaining mental health services. About a quarter of the sample reported experiencing some sort of discrimination in traditional mental health settings, whereas less than 10 percent of participants experienced discrimination in consumer-operated mental health services.

Cross-tabulations were completed to assess the relationship between endorsement of discrimination related to certain characteristics—for example, mental illness, race, or gender—and the area in which discrimination was experienced; these are also included in Table 4. Overall, these findings suggest that people who report discrimination in the areas of employment, housing, or encounters with law enforcement personnel attribute the discrimination to a variety of sources—not only mental illness, but also race, gender, sexual orientation, and physical disability. For example, more than half of participants who reported being discriminated against because of mental illness, race, gender, sexual orientation, or physical disability identified employment as an area in which this prejudice occurred. Subsequent chi square analyses did not show that the area in which discrimination occurred significantly differed between these subgroups.

Discussion and conclusions

The goal of this study was to further elaborate and put some perspective on the stigma experienced by persons with mental illness. The results showed that a little more than half of a sample of 1,824 persons with serious mental illness reported experiencing discrimination. Although the frequency of discrimination in this study again highlights the scope of this problem, it is noticeably lower than the 70 percent reported by Wahl (19). Several possibilities may account for this difference. In Wahl's study, discrimination was reported on a Likert scale, whereas the Discrimination Questionnaire we used framed discrimination categorically. Moreover, Wahl's survey focused specifically on discrimination due to the stigma of mental illness. In the study reported here, we examined multiple causes of discrimination. Perhaps framing discrimination in a broader social light diminished the frequency with which it was identified. Future research needs to continue to understand just the base rates of discriminatory experiences among persons with mental illness.

One of the primary goals of this study was to examine the perceived reasons for discrimination among study participants who believed that they had been discriminated against. At first glance, the most prominent reason seemed to be the person's mental illness rather than other group characteristics associated with stigma, such as race, gender, or sexual orientation—almost three-quarters of the group reporting discrimination had been victims of the stigma associated with mental illness. However, when we accounted for whether the person belonged to a specific outgroup in addition to having a mental illness, two other reasons emerged as equally important in explaining why participants in this study were stigmatized: race and sexual orientation. Black persons and Asian persons reported high rates of discrimination due to their race, and gay and lesbian participants reported similar high rates of discrimination due to their sexual orientation.

Unfortunately, these findings are not surprising. Despite some historical gains in majority views about people of color, persons from minority ethnic groups still experience substantial discrimination (25,26,27). Moreover, sexual orientation continues to be a source of stigma and discrimination for many individuals (28,29). Findings from our analysis suggest that just because people are stigmatized because of their mental illness does not mean that they escape these other two types of prejudice.

The second goal of this study was to identify the areas in which people experience discrimination. About half of the participants who reported discrimination identified employment as the leading area in which discrimination occurred. Other areas in which discrimination seemed relatively frequent were housing and law enforcement. These findings are important in light of a recent call for targeted antistigma programs (submitted manuscript, Corrigan PW, 2002). Namely, instead of seeking to broadly change public opinion about a stigmatized group, antistigma programs should target individual power groups whose discrimination is particularly problematic for persons with mental illness. The results of our analysis show that employers, landlords, and police officers may fall into this category and should be the focus of specific antistigma programs.

It is important to highlight two further limitations of this study. Although the study sample was large, diverse, and drawn from eight states, it was not a probability sample. Thus the sample was not necessarily representative of the American population of persons with serious mental illness. In addition, although certain groups were represented in the sample in proportions that exceed those in the U.S. Census—for example, our sample was 60.1 percent female, whereas the U.S. Census is 50.3 percent female—we had no recruitment strategy that sought to oversample any particular ethnic or gender group. Second, the results of the study represent perceptions of discrimination, not independent evidence. To both conceptually and methodologically split a person's perception of discrimination and independent evidence is a complex task. Nevertheless, future research needs to consider approaches for clarifying this issue.

Finally, it is important to note that discrimination on the basis of race or another group characteristic does not diminish the impact of stigma associated with having a mental illness. Our findings echo Brewer's (20) concerns about dual discrimination; namely, many people identify with more than one social outgroup that is discriminated against by the majority. Unfortunately, research thus far has not tackled concerns about dual discrimination, so explanatory models that might account for the interaction of more than one type of stigma are largely absent. Moreover, antistigma programs have thus far been the province of single-issue groups—for example, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the National Organization for Women, and NAMI. The results summarized in this article demonstrate the complexity of the discrimination problem and the fact that organizations that launch antistigma campaigns may need to partner with one another to more completely tackle the problems caused by stigma.

Dr. Corrigan is affiliated with the University of Chicago Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 7230 Arbor Drive, Tinley Park, Illinois 60477 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Thompson is with the psychology department of the University of Missouri in St. Louis. Dr. Lambert is with the Edmund S. Muskie School of Public Affairs at the University of Southern Maine in Portland. Ms. Sangster is with Advocacy Unlimited in Hartford, Connecticut. Dr. Noel and Dr. Campbell are with the Missouri Institute of Mental Health in St. Louis.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants in a study of perceived discrimination

|

Table 2. Overall frequencies of experiences of discrimination among 949 study participants who reported discrimination

|

Table 3. Frequency of perceived discrimination in subgroups of persons with mental illness who believed they experienced discrimination because of membership in that subgroup

|

Table 4. Areas in which participants reported experiencing discrimination

1. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, 1999Google Scholar

2. Corrigan PW, Edwards AB, Green A, et al: Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:219–225, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Link BG, Phelan JC: Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology 27:363–385, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Penn DL, Kohlmaier JR, Corrigan PW: Interpersonal factors contributing to the stigma of schizophrenia: social skills, perceived attractiveness, and symptoms. Schizophrenia Research 45:37–45, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Clarkin JF, et al: Stigma as a barrier to recovery: adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatric Services 52:1627–1632, 2001Link, Google Scholar

6. Pescosolido BA, Monahan J, Link BG, et al: The public's view of the competence, dangerousness, and need for legal coercion of persons with mental health problems. American Journal of Public Health 89:1339–1345, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Struening EL, Perlick DA, Link BG, et al: The extent to which caregivers believe most people devalue consumers and their families. Psychiatric Services 52:1663–1638, 2001Link, Google Scholar

8. Wright ER, Gronfein WP, Owens TJ: Deinstitutionalization, social rejection, and the self-esteem of former mental patients. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41:68–90, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Campbell J, Schraiber R: The Well-Being Project: Mental Health Consumers Speak for Themselves. Sacramento, California Department of Mental Health, Office of Prevention, 1989Google Scholar

10. Mansouri L, Dowell DA: Perceptions of stigma among the long-term mentally ill. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 13:79–91, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Herman NJ: Return to sender: reintegrative stigma management strategies of ex-psychiatric patients. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 22:295–330, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Link BG: Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review 52:96–112, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening EL, et al: A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. American Sociological Review 54:400–423, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, et al: On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38:177–190, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, et al: Stigma as a barrier to recovery: the consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 52:1621–1626, 2001Link, Google Scholar

16. Rosenfield S: Labeling mental illness: the effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. American Sociological Review 62:660–672, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatric Services 52:1615–1620, 2001Link, Google Scholar

18. Markowitz FE: Modeling processes in recovery from mental illness: relationships between symptoms, life satisfaction, and self-concept. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42:64–79, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wahl OF: Mental health consumers' experience of stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:467–478, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Brewer MB: Reducing prejudice through cross-categorization: effects of multiple social identities, in Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination: The Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Edited by Oskamp S. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 2000Google Scholar

21. Landrine H, Klonoff EA: The Schedule of Racist Events: a measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology 22:144–168, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Klonoff EA, Landrine H, Ullman JB: Racial discrimination and psychiatric symptoms among blacks. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 5:329–339, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Klonoff EA, Landrine H: Cross-validation of the Schedule of Racist Events. Journal of Black Psychology 25:231–254, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Thompson Sanders VL: Perceived experiences of racism as stressful life events. Community Mental Health Journal 32:223–233, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Lowery BS, Hardin CD, Sinclair S: Social influence effects on automatic racial prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81:842–855, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Keough KA, Garcia J: Social Psychology of Gender, Race, and Ethnicity: Readings and Projects. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2000Google Scholar

27. Michalos AC, Zumbo BD: Ethnicity, modern prejudice, and the quality of life. Social Indicators Research 53:189–222, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Hegarty P, Pratto F: Sexual orientation beliefs: their relationship to anti-gay attitudes and biological determinist arguments. Journal of Homosexuality 41:121–135, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Herek GM: The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science 9(1):19–22, 2000Google Scholar