Datapoints: Antipsychotic Polypharmacy in the Ambulatory Care Setting, 1993-2000

Administration of more than one antipsychotic medication concurrently to an individual patient is not formally endorsed by the current American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines for schizophrenia (1) and is considered a late option in the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (2). However, an estimated 30 percent of inpatients with a psychotic disorder are treated with more than one antipsychotic (3).

The study reported here used data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) (4) to determine the prevalence of antipsychotic polypharmacy in ambulatory care. The NAMCS samples a random one-week period of a nationally representative group of visits to active physicians in nonfederal, office-based clinical practice. A total of 232,439 visits were sampled over the eight years, and data were weighted to produce national estimates. All visits during which at least one antipsychotic drug was prescribed, ordered, supplied, administered, or continued were included. Logistic regression was used to compute odds ratios (ORs).

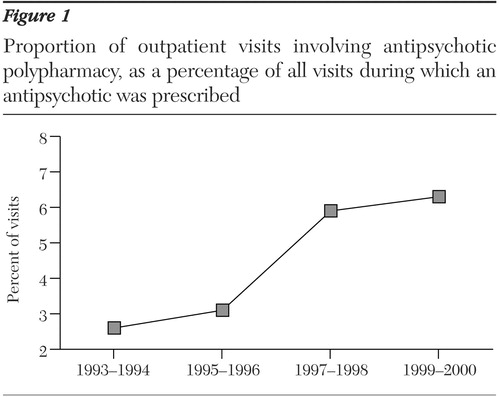

Antipsychotics were reported for 2,368 visits (1 percent). At least two antipsychotics were prescribed or continued at 104 of these visits (4 percent). As shown in Figure 1, the prevalence of polypharmacy increased for each two-year period. A visit involving antipsychotic polypharmacy was 2.5 times as likely to occur in 1999-2000 as in 1993-1994 (OR=2.5, 95 percent confidence limit=1.356 to 4.605, p≤.003).

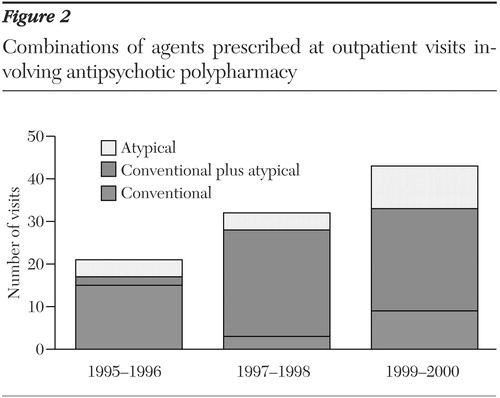

As shown in Figure 2, use of two conventional antipsychotics was predominant in 1995-1996, whereas combining an atypical with a conventional agent or with another atypical agent was more common in 1999-2000. The change in combination patterns likely reflects the increasing availability of several atypical antipsychotics.

The rate of antipsychotic polypharmacy appears to be lower than that among inpatients with serious mental illness. However, polypharmacy in community practice continues to increase, as does the use of atypical antipsychotics in polypharmacy regimens. Despite the large number of visits sampled in this survey, the number that included antipsychotic polypharmacy was small, and thus the findings should be interpreted with caution.

The authors are affiliated with the Research and Data Management Center in the College of Pharmacy at the University of Kentucky, 2351 Huguenard Drive, Suite 100, Lexington, Kentucky 40503 (e-mail, [email protected]). Harold Alan Pincus and Terri L. Tanielian, M.A., are editors of this column.

Figure 1. Proportion of outpatient visits involving antipsychotic polypharmacy, as a percentage of all visits during which an antipsychotic was prescribed

Figure 2. Combinations of agents prescribed at outpatient visits involving antipsychotic polypharmacy

1. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(Apr suppl):1–63, 1997Google Scholar

2. Texas Medication Algorithm Project: Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation. Available at www.mhmr.state.tx.us/centraloffice/medicaldirector/TIMA.html (revised September 2002)Google Scholar

3. Stahl SM: Antipsychotic polypharmacy: part 1. therapeutic option or dirty little secret? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:425–426, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Health Statistics: National Ambulatory Care Survey. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/ahcd/ahcd1.htmGoogle Scholar