Clinical, Social, and Service Use Characteristics of Fuzhounese Undocumented Immigrant Patients

Abstract

This study was a chart review and clinician survey of social, clinical, and service use characteristics among all Fuzhounese patients at a mental health clinic in New York's Chinatown from 1998 through 2000. Of a total of 216 clinic patients, 63 (29 percent) were Fuzhounese, and 32 (51 percent) of them were undocumented immigrants. This group, relative to comparison groups of 31 documented Fuzhounese patients and 62 documented non-Fuzhounese Chinese patients, had higher rates of hospitalization and rehospitalization, lower treatment compliance and insight into illness, and many social disadvantages, indicating a strong association between undocumented status and poorer mental health outcome. The authors suggest potential changes in treatment and health policy.

In recent decades, more than 300,000 Fuzhounese people, from the environs of Fuzhou in Fujian province, have left that eastern Chinese coastal region and have moved to other countries to seek social and political stability, prosperity, and better education; to join family members; and to escape a variety of problems. A majority of these immigrants are undocumented (1).

Many Fuzhounese become victims of human smuggling rings, often paying $30,000 or more to be transported illegally to another country. Tragedies that befall illegal immigrants fleeing their homelands catch the world's attention, and the plight of Fuzhounese people is a prime example: 58 died of suffocation in a truck in Dover, England, and ten drowned in the Golden Venture shipwreck in New York (1).

Typically, the immigrant makes a small partial payment before the journey begins, and relatives or friends who are already living in the destination country agree to pay the smugglers the remainder within seven days of the immigrant's arrival. Then the immigrant pays back the relatives, with interest, over the next few years —an enormous undertaking, given the low wages of undocumented workers.

In recent years more than 100 Fuzhounese have settled in the New York tristate area (1). They are part of the 300,000 illegal immigrants arriving in the United States annually (2). Undocumented Chinese immigrants generally work for Chinese employers, some of whom often ignore U.S. labor laws and isolate and exploit the workers.

Collectively, the Fuzhounese illustrate many representative themes of international migration (3). However, little research exists on the mental health characteristics of undocumented immigrants who settle in the United States. This study examined demographic, clinical, and service use characteristics of a group of Fuzhounese patients with a view to improving clinical understanding of undocumented immigrants in general and stimulating discussion on psychiatric treatment strategies and policy planning.

Methods

We conducted this study at the Asian Bi-Cultural Mental Health Clinic in New York's eastern Chinatown. The clinic, operated by the New York City Health and Hospital Corporation, has seven full-time staff. Appointments are conducted in Mandarin, because no staff speak Fuzhounese.

From the clinic's year 2000 patient list, we identified all 63 Fuzhounese patients. Not all patients had attended the clinic for the entire 1998-2000 period; our comparison analysis accounted for that fact by controlling for the period patients attended the clinic. The 32 patients who were undocumented constituted the study group, and the 31 documented patients were the comparison group. We randomly selected 62 non-Fuzhounese Chinese patients at the clinic as a second comparison group. Almost all non-Fuzhounese patients were documented. The sample including all three groups totaled 125.

We performed a chart review and gathered data from the clinic's patient registry and billing database. We also gathered data from the health data system of Bellevue Hospital Center, where 98 percent of the study participants' hospitalizations occurred. This study was approved by the local research review committee and the internal review board of the New York City Health and Hospital Corporation.

We also surveyed clinicians about subjects' insight into their illness. Clinicians rated patients on a three-point Likert scale. A patient who is given a rating of 1 (high) realizes that he or she has a mental illness and is motivated to receive treatment and follow-up. A rating of 3 (low) is given to a patient who does not believe or think that he or she is mentally ill, is very passive, or resists treatment and follow-up. A rating of 2 (moderate) is for patients who fall in between.

Methods for intergroup comparisons (alpha=.05), for which we used SPSS version 10, included chi square tests for categorical dependent variables, binomial tests when table cells' expected frequencies fell below 5, z score approximations based on a Holm's sequential Bonferroni adjustment, one-way analyses of variance for continuous dependent variables, and analyses of covariance for continuous dependent variables when another variable was being controlled for.

Results

Of the 216 active patients in the clinic, 63 (29 percent) were Fuzhounese, and 32 of the Fuzhounese (51 percent) were undocumented. In the undocumented Fuzhounese group the mean±SD age was 28.8±6 years, in the documented Fuzhounese group it was 46.9±14 years, in the non-Fuzhounese group it was 39.1±14.3 years, and in the total group it was 39.1±14.3 (F=28.19, df=2, 122, p<.001). The undocumented Fuzhounese group included 23 men (72 percent) and nine women (28 percent); the documented Fuzhounese group, 11 men (36 percent) and 20 women (65 percent); the non-Fuzhounese group, 26 men (42 percent) and 36 women (58 percent); and the total sample, 60 men (48 percent) and 65 women (52 percent).

Compared with their documented counterparts, patients who were undocumented had distinctive and significant demographic differences and social disadvantages. They were significantly younger (F=28.19, df=2, 122, p<.001) and more likely to be male (χ2=10.17, df=2, p<.01) than the non-Fuzhounese group. Compared with either documented group, the undocumented group had more recently arrived in the United States (χ2=63.85, df=4, p<.001). The undocumented group members were more likely to live in Chinatown (χ2=11.95, df=2, p<.01) and to have current debt (z approximation, p<.001), and they were less likely to have private or publicly funded health insurance (χ2=37.44, df=2, p<.001) and to have family in the United States (χ2=48.99, df=2, p<.001). These individuals were more likely to have had past legal charges (χ2=9.23, df=2, p<.01). However, their legal problems were mostly immigration matters and illness-related public disturbance charges, and the level of violent acts was no higher than among patients who were documented.

Undocumented patients worked more regularly but without correspondingly higher incomes. Only four patients in the entire sample earned more than $30,000 a year, and only four held office or professional jobs; the vast majority were laborers. More participants were single than married in all three groups, but the undocumented Fuzhounese had by far the greatest proportion of single persons (68 percent). This group ranked a low second in the proportion of persons with some high school education.

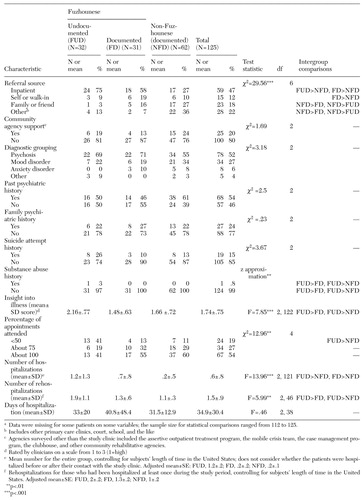

Clinical characteristics and service use characteristics are shown in Table 1. Although all three groups had similar clinical diagnoses and personal and family psychiatric histories, the routes of referral to the clinic were strikingly different. Patients in the undocumented Fuzhounese group came predominantly from inpatient hospital settings, and patients in the other two groups were mainly self- and family referrals. All groups showed low levels of support from or use of community and rehabilitative services, although more than 60 percent of the participants had psychotic illnesses. Importantly, clinicians viewed the undocumented Fuzhounese patients as having the least insight into their illnesses. Also notable were the very low rate of substance use or abuse among all the groups and a nonsignificant trend toward higher suicide rates in the undocumented group.

After length of stay in the United States was controlled for, patients in the undocumented Fuzhounese group had six times the risk of being hospitalized as the non-Fuzhounese group and almost twice the risk of the documented Fuzhounese group. In addition, the rehospitalization rate for the undocumented group was almost twice as high as the rate for both comparison groups. Nevertheless, lengths of hospitalization for all three groups were similar.

The Fuzhounese patients as a group had a shorter duration of treatment at the clinic, and undocumented Fuzhounese patients attended their appointments less often than the documented non-Fuzhounese. Otherwise, all three groups were similar in frequency of visits to psychiatric, medical, and walk-in facilities at the clinic and its associated services.

Discussion and conclusions

This study had limitations. The sample size was limited, and we lacked Fuzhounese-speaking staff to gain in-depth knowledge of the patients. In addition, we examined a patient sample at a single clinic. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to all undocumented Fuzhounese persons.

However, the strikingly higher hospitalization and rehospitalization rates among undocumented Fuzhounese patients were alarming in light of these patients' lack of insurance and low insight. The findings suggested that these patients, probably for fear of deportation, waited till they were desperate or severely ill before seeking help. Most patients who were undocumented had a route of referral through tertiary care services, suggesting that these undocumented immigrants, like other marginalized groups, relied on emergency services and tertiary hospitals with Medicaid-funded services as their primary forms of mental health care (4). Lack of timely and accessible psychiatric services threatens undocumented persons' quality of life and also probably imposes large costs on the public health system (5).

Several factors encountered in this study contribute to a higher risk of rehospitalization. Prime examples are the policy-driven uniform duration of hospital stay and the resulting difficulties in meeting basic discharge planning requirements—for example, reliable accommodation, medication, support, and follow-up—as well as low rates of attendance at appointments for treatment, lack of community resources and aftercare, and lack of Fuzhounese-speaking clinical staff (6,7,8). Sizable appointment fees—$20 to $40—may also contribute to lack of ongoing treatment and consequent rehospitalization.

A series of large multicenter studies (9) showed that people with severe mental illnesses fared better in developing countries as a result of acceptance and support by family and community. Undocumented Fuzhounese persons in the United States have lost such protection, and they live in the shadow not only of deportation but of other social disadvantages, as discussed here. Lack of support and acute social disadvantages are significantly associated with poor functioning in general and, for persons with vulnerability to mental illness, constitute risk factors for decompensation and hospitalization (6,7,8).

The characteristics of the overall clinic population were also remarkable, because the clinic cares for mostly severely ill patients. For example, almost the entire study population had either psychosis (55 to 71 percent for the three groups) or mood disorders (20 to 34 percent). Although diagnoses were statistically evenly distributed among the groups, treatment outcomes were markedly worse for the undocumented Fuzhounese immigrants. The 2001 Surgeon General's report showed that ethnic minority groups in general tend to receive inferior mental health care (10). The findings of this study suggest that this harsh reality is aggravated among persons who are both ill and undocumented.

The study highlighted a number of service areas that probably affect mental health outcomes and in which improvements are needed. Clinic-level responses may include increasing staff cultural expertise by hiring Fuzhounese staff and holding cultural education workshops. To improve patients' access to services, flexible schedules and follow-up that respond to patients' employment, active case management, and additional services from the clinic's assertive outreach team would complement better community mental-health education targeting the Fuzhounese. Reexamining appointment fee structures and advocating for Medicaid reimbursement for outpatient services would probably improve outcomes.

Funding and service issues imply questions about the roles of city, state, and federal government mental health systems and about the underlying relationship between the need for basic health care and immigration-related restrictions. A wider and more active discourse on the mental health needs of undocumented immigrants is needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yu-Wen Chou, Ph.D., Yuen-Fan Wong, M.S.W., Teddy Chen, M.S., Florence Kwong, M.S.W., Tony Cheng, M.S.W., Yeung-Wai Ng, Edgar Velazquez, M.D., Louis Caponi, M.D., Julio Santos, Kelly Gallagher-Mackay, LL.M., Stephen Rosenheck, M.S.W., and Jules Ranz, M.D., for their invaluable input.

Dr. Law is affiliated with the department of psychiatry of St. Michael's Hospital, 30 Bond Street, 17th Floor, Cardinal Carter Wing, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5B 1W8 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Hutton and Dr. Chan are with the Gouverneur Diagnostic and Treatment Center at Behavior Health in New York City.

|

Table 1. Pairwise comparisons of clinical and service use characteristics of 125 Chinese immigrant patientsa

a Data were missing for some patients on some variables; the sample size for statistical comparisons ranged from 112 to 125.

1. Chin KL: Smuggled Chinese: Clandestine Immigration to the United States. Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1999Google Scholar

2. Passel JS: Illegal Immigration: How Big a Problem? Washington, DC, Urban Institute Press, 1995Google Scholar

3. Massey D, Arango J, Hugo G, et al: Theories of international migration: a review and appraisal. Population and Development Review 19:431–466, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Burnett R, Mallett R, Bhugra D, et al: The first contact of patients with schizophrenia with psychiatric services: social factors and pathways to care in a multi-ethnic population. Psychological Medicine 29:475–483, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lyons JS, O'Mahoney MT, Miller SI, et al: Predicting readmission to the psychiatric hospital in a managed care environment: implications for quality indicators. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:337–340, 1997Google Scholar

6. Kent S, Yellowlees P: Psychiatric and social reasons for frequent rehospitalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:347–350, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Fisher WH, Geller JL, Altaffer F, et al: The relationship between community resources and state hospital recidivism. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:385–390, 1992Link, Google Scholar

8. Klinkenberg WD, Calsyn RJ: Predictors of receipt of aftercare and recidivism among persons with severe mental illness: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:487–496, 1996Link, Google Scholar

9. Sartorius M, Jablensky A, Korten A, et al: Early manifestations and first contact incidence of schizophrenia in different cultures: a preliminary report of the initial evaluation phase of the WHO study of determinants of outcome of severe mental disorder. Psychological Medicine 16:909–928, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Satcher D: Mental Health: Culture, Race, Ethnicity. Supplement to Mental Health: Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2001Google Scholar