An Automated Treatment for Jet Lag Delivered Through the Internet

Abstract

Seventy percent of persons who suffer from psychiatric illness do not receive treatment. Cost-effective, automated treatment can be delivered through the Internet but can be complicated by the lack of professional supervision. This open study piloted a fully automated, publicly available treatment for jet lag as a means of highlighting some of the issues involved in delivering treatment over the Internet. Twenty study participants rated the severity of their jet lag symptoms and their adherence to a light-exposure schedule calculated to accelerate adaptation to a new time zone. A significant negative correlation was observed between how closely participants followed the light-exposure schedules and the severity of their jet lag symptoms.

Seventy percent of Americans with mental health disorders do not receive treatment (1). The use of computer-assisted therapy is one way of approaching this problem. Applications designed to provide psychotherapy have been developed for a number of conditions. Some are designed to run on stand-alone computers (2), whereas others have relied on the Internet to expand their reach (3). On-line therapy allows communication by e-mail or other forms of message exchange (4) but does not necessarily reduce the amount of therapist time needed to treat a patient. Partially automated interventions require less therapist involvement (5), whereas fully automated systems can be scaled to serve as many patients as desired (6). Although fully automated Internet-based programs have the greatest potential for expanding access, a major challenge is that they are unsupervised.

This report describes a fully automated treatment for jet lag, delivered over the Internet, involving the use a calculated schedule of exposure to bright light to reduce the severity of jet lag symptoms.

Jet lag occurs when an individual's circadian rhythms become desynchronized after a trip across several time zones. Common symptoms of jet lag include insomnia, fatigue, cognitive impairments, and negative mood states. Symptoms tend to peak one day after the person arrives at his or her destination and then gradually diminish (7). Although the symptoms of jet lag can lead to significant impairment and distress, they tend to be less severe than the symptoms of other psychiatric illnesses and therefore appropriate for investigation through an unsupervised intervention.

Scheduled exposure to bright light can alleviate the symptoms of jet lag by accelerating adaptation to the new time zone (8). The effect of bright light on circadian rhythms varies by time of exposure, and phase-response curves have been obtained (9). To have an effect on circadian rhythms, the intensity of light must be at least 2,500 lux. Indoor light in a room with shaded windows ranges from 100 to 500 lux. Outdoor light ranges from 5,000 lux on a cloudy day to greater than 20,000 lux in bright sunlight. Therapeutic lamps provide 10,000 lux. To affect phase adaptation, exposure to outdoor light or a therapeutic lamp is required.

Methods

The treatment program was posted to the Internet and registered with the major search engines. Visitors to the Web site were asked to enter six pieces of data about their trip: originating city, destination city, date of outbound trip, time of outbound trip, date of return trip, and time of return trip. Visitors to the Web site did not enter their name or any other identifying information. Individuals who were known to the investigator and who were planning to travel overseas were asked to visit the Web site; most of the study participants who completed rating scales visited the Web site as a result of such a request. Data from participants who were recruited directly were not distinguished from data submitted by other participants.

On the basis of the trip data, a schedule of light exposure and avoidance was generated. Travelers were advised to spend as much time as possible outside or next to a bright window during exposure times and to avoid exposure to daylight or wear sunglasses during avoidance times. Therapeutic lamps were not used.

Respondents were not paid for their participation in the study, and none of the visitors to the Web site were charged for accessing the site. The informed-consent process, like the treatment itself, was fully automated. The study was approved by the George Washington University's institutional review board.

Study participants were asked to periodically complete the Columbia Jet Lag Scale (7) as a measure of severity of symptoms. They were also asked to rate how closely they followed the light schedule. There was no control condition. Data were collected between June 2000 and January 2001. Reported severity of jet lag symptoms on day 3 of the trip was the focus of the analysis. Day 3 was chosen because it is the earliest day one can expect to see a robust effect of the intervention. Jet lag resolves rapidly after short trips, so selecting the earliest possible time to measure symptoms allowed the inclusion of the maximum number of trips.

Results

A total of 4,644 people visited the Web site. Visitors to the site were from countries on all continents except Antarctica. Twenty individuals, most of whom had been directly solicited by the investigator, returned completed surveys. The average trip crossed eight time zones. Treatment compliance was measured on a scale of 0 to 4 and averaged 2.5. Severity of symptoms was also measured on a scale of 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater severity, and averaged 1.3 on day 3. Travelers who reported greater compliance with the intervention reported significantly less severe symptoms on day 3 (two-tailed Pearson correlation=−.47, p<.01). When the number of time zones crossed was controlled for, the partial correlation coefficient was −.41 (p=.027). The correlation between the number of time zones crossed and compliance was not significant.

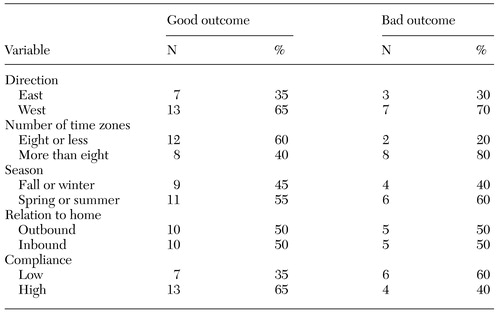

To help evaluate several possible explanations for these findings, study participants were divided into two groups based on whether they had a "good" outcome (a severity outcome score of less than 2) or a "bad" outcome (a severity outcome score of 2 or more). The distribution of these groups was evaluated according to several different variables, which are listed in Table 1. Travelers who crossed more than eight time zones reported more severe symptoms of jet lag than those who crossed eight or fewer time zones (χ2=4.3, df=1, p<.05).

Discussion

This project was designed to highlight some of the issues involved in delivering treatment over the Internet. The management of jet lag was chosen because calculating a complex light-exposure schedule is well suited to a computer. Furthermore, the risks associated with timed light exposure are minimal, so it was possible for the institutional review board to approve a fully automated informed consent process as well as freely available treatment in the absence of professional supervision.

In addition to safety, the issue of confidentiality is central to the delivery of psychiatric interventions over the Internet (10). The Internet is a public medium and inherently insecure. This problem was addressed simply and directly by avoiding all personal data.

No funds were spent on advertising or providing incentives to potential participants. However, most of the 20 participants who returned data were directly asked to use the Web site. Over an eight-month period, more than 4,600 individuals visited the site, which suggests that interest can be generated by simply making a treatment publicly available. Because no identifying information was collected, it was not possible to contact study participants who did not return completed surveys. Only 20 visitors to the site spontaneously provided completed surveys, thereby introducing the possibility of a large selection bias. A program that automatically stored clinical data as participants interacted with it might be more successful in collecting data.

A significant negative correlation was found between the severity of jet lag symptoms on day 3 and the reported level of compliance with the light-exposure schedule. One limitation of this study was the lack of a control condition. Thus this effect cannot be linked causally to the intervention. Participants who made the effort to adhere to the schedules might have expected diminished symptoms of jet lag and been influenced by their expectation. Conversely, those who had less severe symptoms might have rated their compliance higher than their actual behavior justified. Another limitation was the small sample.

Conclusion

It is possible to use the Internet to treat jet lag in the absence of professional supervision. Future studies will need to continue to focus on privacy, confidentiality, and the ethical issues associated with fully automated, publicly available treatment for jet lag and other conditions.

Dr. Lieberman is assistant professor and director of clinical services in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University, 2150 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20037 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Distribution of outcomes of automated treatment for jet lag among 20 participants in a Web-based survey

1. Goldman HH, Rye P, Sirovatka P (eds): Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar

2. Greist JH: Computer interviews for depression management. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(suppl 16):20-24, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bai Y-M, Lin C-C, Chen J-Y, et al: Virtual psychiatric clinics. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1160-1161, 2001Link, Google Scholar

4. Humphreys K, Klaw E: Can targeting nondependent problem drinkers and providing Internet-based services expand access to assistance for alcohol problems? A study of the Moderation Management self-help/mutual aid organization. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 62:528-532, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Tate DF, Wing RR, Winett RA: Using Internet-based technology to deliver a behavioral weight loss program. JAMA 285:1172-1177, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ochs EPP, Binik YM: A sex-expert system on the Internet: fact or fantasy? Cyberpsychology and Behavior 3:617-629, 2000Google Scholar

7. Spitzer RL, Terman M, Williams JB, et al: Jet lag: clinical features, validation of a new syndrome-specific scale, and lack of response to melatonin in a randomized, double-blind trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1392-1396, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Brown GM: Light, melatonin, and the sleep-wake cycle. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 19:345-353, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

9. Gundel A, Spencer MB: A mathematical model of the human circadian system and its application to jet lag. Chronobiology International 9:148-159, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Manhal-Baugus M: E-therapy: practical, ethical, and legal issues. Cyberpsychology and Behavior 4:551-563, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar