Rates of Refusal to Participate in Research Studies Among Men and Women

Abstract

Studies have indicated that, among persons with serious mental illness, women may be less likely to participate in clinical research studies than men. This study examined refusal rates by gender in four recent studies that included persons with a range of diagnoses and that used various interventions and methods. Examination of the four studies indicated that women are no more likely than men to decline to participate in studies but that women may be underrepresented in target populations. When feasible, oversampling may be useful to increase the participation of women or of any other underrepresented demographic group in research studies.

The recruitment of women and persons from minority groups into research studies is an important issue both for researchers and for funding sources. Studies have suggested that, among persons with serious mental illness, women are less likely than men to participate in research studies. Most of these reports come from studies of persons with a narrow range of diagnoses, and most have been limited to medication trials.

Perhaps the strongest evidence of gender bias in study recruitment comes from a randomized controlled trial, conducted by Robinson and colleagues (1), of the effectiveness of medication combined with psychoeducational family therapy for long-term maintenance among patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. In that study, eligible women refused participation more frequently than did eligible men. Mohr and Czobor (2) found that fewer women participated in placebo-controlled trials than in comparator-controlled trials. Spohn and Fitzpatrick (3) provided evidence that women's participation in research studies is related to whether or not a placebo is used. These researchers noted that women with schizophrenia were significantly less likely than men with schizophrenia to consent to participate in a study that included a placebo washout period. In contrast, Hofer and colleagues (4) noted that, among persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, gender did not predict the likelihood of agreeing to participate in phase III clinical trials, which often include a placebo condition.

The purpose of the study reported here was to examine rates of participation by gender in studies that included a broader range of participants, treatments, and methods than those previously examined.

Methods

We examined recruitment data from each of the completed studies we conducted since 1990 that included persons with serious mental illness. Participants in all studies signed consent forms that had been approved by our institutional review board and received modest remuneration for their participation ($8 to $18 per hour). The investigators in these studies were affiliated with academic institutions, but all treatment sites were routine practice settings funded by the state mental health system.

Clozapine study

From November 1991 through August 1992, clinical staff approached patients in state hospitals who had a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and who met other study eligibility criteria (5). Participants in the clozapine study were randomly assigned either to begin taking clozapine or to continue receiving conventional antipsychotic medications. The final study sample of 227 was 61 percent male (138 patients), 84 percent Caucasian (190 patients), 10 percent African American (22 patients), and 6 percent Hispanic (14 patients). At study entry, the participants had a mean±SD age of 41±11.6 years.

Assertive community treatment study

Between August 1993 and July 1998, clinical and research staff approached outpatients at two state-operated, urban outpatient mental health centers who had a diagnosis of both a serious mental illness and a substance use disorder for participation in an assertive community treatment study that delivered integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment (6). Participants were randomly assigned to receive this treatment as delivered by either an assertive community treatment team or a standard case management team. The final study sample of 199 was 71 percent male (142 patients), 58 percent African American (115 patients), 41 percent Caucasian (81 patients), and 15 percent Hispanic (29 patients). At study entry, the participants had a mean age of 37±7.8 years.

Risk study

Between June 1997 and December 1998, research staff approached patients at two state-operated, urban outpatient mental health centers to participate in a multisite cross-sectional study examining serostatus for HIV, hepatitis, and associated risk behaviors among persons with serious mental illness (7). Most of the patients who were approached (143 patients, or 91 percent) had previously consented to participate in the assertive community treatment study. The participants provided a blood sample and completed a standardized interview. The final study sample of 158 was 74 percent male (117 patients), 53 percent African American (84 patients), 27 percent Caucasian (43 patients), and 11 percent Hispanic (18 patients). The participants had a mean age of 40±7.8 years.

Jail diversion study

From November 1997 through April 2000, research staff approached persons with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders who were facing charges in state criminal courts. The experimental group in this jail diversion study included persons who were facing charges in courts that had mental health diversion programs, and the comparison group included those who were facing charges in courts that did not have such programs. Participation in the study did not affect the status of these individuals' criminal cases. The final study sample of 211 was 74 percent male (157 persons), 44 percent African American (93 persons), 32 percent Caucasian (67 persons), and 23 percent Hispanic (49 persons). The participants had a mean age of 35±8.8 years.

Data analysis

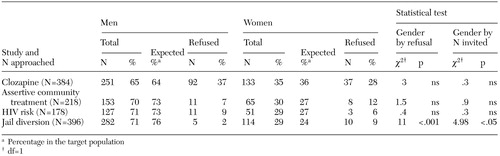

A person who was eligible for a study and who was invited to participate but declined was designated as a refuser. For each study, we constructed a 2 × 2 table—refusal (yes or no) by gender (male or female)—and applied chi square analyses to determine whether the ratio of male to female refusers differed significantly from what we would expect given the ratio of men to women among those invited to participate. We used chi square goodness-of-fit tests to examine whether the gender distribution of persons who were eligible for study participation differed significantly from the gender distributions in the population from which they were drawn.

Results

With one exception, the proportion of men and women who were invited to participate in a study resembled the gender distributions in the target populations, as can be seen in Table 1. In the jail diversion study, women were more likely than men to be invited to participate. Across all four studies, neither gender had consistently higher refusal rates. In the clozapine study, men were marginally more likely to refuse to participate. In the assertive community treatment and risk studies, no gender differences in refusal rates were observed. In the jail diversion study, women were significantly more likely than men to refuse to participate.

Discussion

The data presented here do not support the generalization that women with serious mental illness are more likely than men to refuse to participate in research studies. Indeed, in the study that most closely resembled other randomized trials of medication effectiveness (1,2,3)—the clozapine study—refusal rates for men were marginally higher than those for women. The large gender differences in refusal rates across the studies suggest that refusal rates may be influenced by characteristics of the study design and population.

As is the case with other published studies involving this patient population, the number of men participating in these studies far exceeded the number of women. The studies had target populations ranging from 64 percent to 76 percent male, and their eligibility criteria did not differentially exclude women. Women and men refused in roughly equal rates, which resulted in samples with gender distributions reflecting that of the target populations. Thus, to increase the proportion of women or other underrepresented groups in studies of persons with serious mental illness, future studies may need to oversample women. However, we recognize that there are times when researchers approach 100 percent of the target population, which makes oversampling impossible.

One limitation of our study was the fact that the investigators in the risk study approached primarily persons who had already consented to participate in a previous study (the assertive community treatment study). Thus it might be said that the participants in that study were already willing to participate in research. However, many other reports of gender bias in study participation also include persons who have participated in previous research.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that either men or women may be more willing to participate in a research study, depending on the study, and that the gender distributions of persons who are invited to participate in a study and who agree to do so generally match those of the target populations. However, women are underrepresented in research studies of persons with serious mental illness, which suggests that future studies should consider oversampling to include more women in studies of persons with serious mental illness.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by Public Health Service grants R01-MH-48330, R01-MH-52872, and R01 MH-52872S from the National Institute of Mental Health; grant R01-AA-10265 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; grants UD3-SM-51560 and UD3-SM-51802 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Public Health Service grant U1G-SM-52096 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Hartford; and the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of the Veterans Integrated Service Network 3. The authors also acknowledge support from the psychology department and the A. J. Pappanikou Center at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and from the medication effectiveness research program at Yale University, funded by grant R24-MH-54446 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Covell and Dr. Frisman are affiliated with the department of psychology at the University of Connecticut in Storrs and with the research division of the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services in Hartford. Dr. Essock is with the department of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City and with Veterans Affairs New York Healthcare System, Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, in the Bronx, New York. Send correspondence to Dr. Covell at DMHAS Research Division, 410 Capitol Avenue, MS 14RSD, P.O. Box 341431, Hartford, Connecticut 06134 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Participation refusal rates in four research studies, by gender

1. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Pollack S, et al: Subject selection biases in clinical trials: data from a multicenter schizophrenia treatment study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 16:170–176, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mohr P, Czobor P: Subject selection for the placebo- and comparator-controlled trials of neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 20:240–245, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Spohn HE, Fitzpatrick T: Informed consent and bias in samples of schizophrenic subjects at risk for drug withdrawal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 89:79–92, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hofer A, Hummer M, Huber R, et al: Selection bias in clinical trials with antipsychotics. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 20:699–702, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Essock SM, Hargreaves WA, Dohm FA, et al: Clozapine eligibility among state hospital patients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:15– 25, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Mueser KT, Essock SM, Drake RE, et al: Rural and urban differences in patients with a dual diagnosis. Schizophrenia Research 48:93–107, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al: Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 91:31–37, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar