An Exploratory Analysis of Behavioral Health Care Use Within Families

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: The authors studied enrollees in employer-sponsored managed health plans to determine the extent of multiple behavioral health consumers within families, use of behavioral health services by employees who have another family member using such services, congruence of diagnoses between two family members using behavioral health services, and the effect on covered charge per behavioral health consumer when other family members use behavioral health services. METHODS: Claims data from 911 plans sold or managed by a single managed behavioral health care company were examined. The plans provided coverage for 724,789 employees and covered about 1.7 million lives. Family members of employees were identified by the relationship codes on the claims. Service utilization rates were calculated for employees overall and for employees who had spouses or children who used behavioral health services. Mean and median covered charges were determined and were examined by number and type of consumers in the family. RESULTS: The use of behavioral health services was greater among employees whose children or spouses used behavioral health services. Utilization rates varied by the child's or spouse's diagnoses. More than 50 percent of male employees whose children received treatment for a depressive disorder also received such treatment. Congruence of diagnoses within families was noted. Covered charges per person generally increased with the number of family members who used behavioral health services. CONCLUSION: Greater knowledge about patterns of use of behavioral health services within families may help in improving access to care and developing more effective family interventions.

Although a considerable amount of research has been conducted on factors that influence the use of behavioral health care services (1,2,3,4), there has been little research on the use of these services within families. Additional knowledge about use of behavioral health services within families is likely to be important from an epidemiological perspective and may help improve access to care. First, epidemiological studies have shown that many mental illnesses have a genetic component (5). Second, members of the same family share environmental risks. The presence of a family member with mental illness could increase the stress level of the household, and stress is an environmental risk (6,7,8). Family functioning can also be a risk factor; for example, being in an unhappy marriage is a risk factor for depression (9). Third, when one family member uses services, other family members obtain information on how to gain access to care. Finally, family members may have similar attitudes about obtaining care and about the kind of care they want to receive.

The limited research that is available suggests that there are family interactions in service use. A strong influence of parents' use of health care services on their children's use of health and mental health services has been reported in several studies (10,11,12). Marital status—in particular, divorce or separation—affects the use and costs of adults' health care services (13,14). Patterns of differential use based on household composition and the presence of a disabled person have also been documented (15).

The availability of a large claims database from a behavioral health care company gave us a unique opportunity to examine service use patterns among privately insured families in a population of more than a million covered lives. Because eligibility data were not available, our analyses focused on behavioral health consumers who were identified from claims data and information about enrollees of employer-sponsored health plans. We considered three research questions. First, if a family member other than the employee uses behavioral health care services, is the employee more likely to use such services? Second, if two family members use behavioral health care services, do their claims list similar diagnoses? Third, what happens to the cost per consumer when other family members also use behavioral health services?

Methods

Data

We used insurance claims data from a set of plans sold or managed by a large managed behavioral health care company. The plans selected for the study were effective for the full 1996 calendar year and covered about the same number of employees each month. These criteria were used to identify plans that had a stable enrollment. This approach produced a sample of 911 plans with 724,789 enrolled employees and an estimated 1.7 million covered lives. All behavioral health care claims for services incurred in 1996 were included. The companies that sponsored the plans were varied, and enrolled employees live in all 50 states. Benefit structures varied considerably across plans.

Enrollment status

Individuals who used behavioral health care services were identified in the data by their enrollment status—employee, spouse, child, or other dependent. Only .2 percent of consumers were enrolled as other dependents, and more than 90 percent of these were under 19 years of age. Thus we combined other dependents and children and categorized them as children. We classified both employees and spouses as adults.

Family definition

Because eligibility files were not available, we focused exclusively on persons who used behavioral health services. In these analyses we defined a family on the basis of the observed use of these services. Any person who used behavioral health care services was defined as a consumer. The size of a family was defined by the number of behavioral health consumers in that family, not by the number of actual family members. Thus an employee who used behavioral health services and had no enrolled dependents and an employee who used such services and had numerous enrolled dependents, none of whom used behavioral health services, would both be defined as one-consumer families.

Assigning claims

A behavioral health claim was defined as any accepted and processed insurance claim with an associated behavioral health diagnosis. For some analyses we classified consumers into specific diagnostic categories: those with claims involving a depressive disorder, those with claims involving a substance use disorder, those with claims involving serious mental illness (essentially a bipolar or psychotic disorder), and those with claims involving attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, depending on the diagnosis coded on the claim. (Code classifications are available from the first author on request.) A consumer with more than one claim could be classified as a member of more than one of these diagnostic groups if different claims listed different diagnoses.

Intensive use

We classified individuals as either intensive or nonintensive consumers, according to their level of service use. On the basis of discussions with behavioral health clinicians and managed behavioral health care organizations, we classified adults as intensive consumers if they had at least ten outpatient visits or any inpatient admission during the study year. We classified children as intensive consumers if they had at least six outpatient visits or any inpatient admission during the study year.

Covered charges

We focused on covered charges, which reflect the price of a service negotiated between the managed behavioral health care organization and service providers. Covered charges are used as a surrogate for the cost of care.

Service use

We determined overall service use by dividing the number of consumers who filed a claim in 1996 by the estimated number of covered lives. Service use rates were determined for all employees and for those who had a spouse or a child who used behavioral health services. We were able to determine separate rates for employees who had dependents who used behavioral health services, because every dependent filing a claim had to be associated with an enrolled employee.

Statistical methods

Without eligibility data, we were limited in the types of statistical analyses we could conduct. However, we used the chi square test to assess differences in categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis H test to determine whether the average covered charges for individuals varied by type of family.

Results

Overall use

In 1996 a total of 124,744 individuals (about 9 percent of all covered lives) had at least one behavioral health claim. These included 92,765 adults (62,357 employees and 30,408 spouses) (74 percent), and 31,979 children (26 percent). These individuals came from 106,858 families of consumers.

Service use

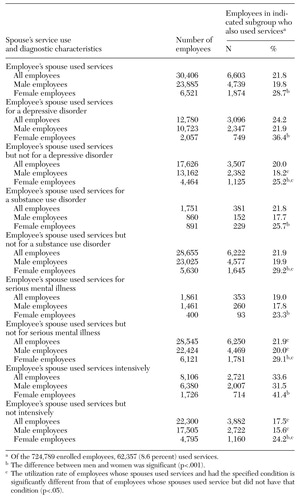

We first considered whether the use of behavioral health services by one family member increased the likelihood that another family member would use these services. With the available data, we were able to examine this question for employees only. The results are summarized in Table 1.

A total of 30,406 employees (4 percent) had a spouse who used behavioral health services. Of these employees, 21.8 percent used behavioral health services, a rate considerably higher than the overall employee utilization rate of 8.6 percent. Use of behavioral health services varied with the spouses' diagnoses. For example, 24.2 percent of employees whose spouse used services for a depressive disorder used behavioral health services themselves, compared with 20 percent of employees whose spouse used behavioral health services but not for a depressive disorder. However, employees who had a spouse who used services for serious mental illness were less likely to use behavioral health services than those who had a spouse who used behavioral health services but not for serious mental illness.

In addition, use of services by employees with a spouse who used behavioral health services intensively was significantly higher than use by employees with a spouse who used these services but not intensively (33.6 percent compared with 17.5 percent). Similar patterns were observed when employee data were disaggregated by sex. However, the rates for female employees whose spouses used behavioral health services were consistently and significantly higher than those for male employees whose spouses used these services, both overall and by diagnostic group.

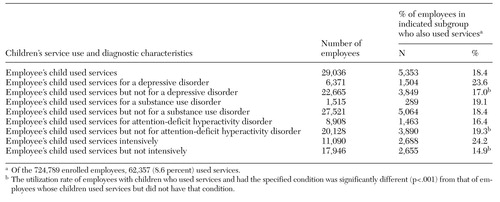

As Table 2 shows, similar associations were observed between employees' use of behavioral health services and their children's use. Overall, 18.4 percent of employees whose children used behavioral health services used behavioral health services themselves, a rate considerably higher than employees' overall utilization rate of 8.6 percent. The use of behavioral health services by this subset of employees also varied by the child's diagnosis. For example, 16.4 percent of employees with a child who used behavioral health services for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder used behavioral health services themselves, compared with 23.6 percent of employees with a child who used behavioral health services for a depressive disorder. Furthermore, the utilization rate of employees whose children were intensive consumers of behavioral health services was considerably higher than the rate of employees whose children used behavioral health services but were not intensive users (24.2 percent compared with 14.9 percent).

Congruence of disorders within families

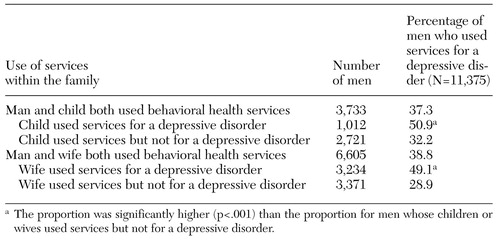

We next examined the extent of congruence in disorders among family members. We looked specifically at depressive disorders, substance use disorders, and serious mental illness. Table 3 lists data on use of services for depressive disorders among adult male consumers and members of their families. The men were significantly more likely to have a claim involving a depressive disorder if a member of their family had such a claim.

For example, focusing on families in which both a man and a child had a behavioral health claim, we observed that 51 percent of men who had a child with a claim involving a depressive disorder filed such a claim themselves, whereas only 32 percent of men who had a child with a claim involving a diagnosis other than a depressive disorder filed a claim involving a depressive disorder themselves.

A similar pattern was observed for congruence of claims involving depressive disorders in all other combinations of consumers—wife and husband, woman and child, and child and parent. We found a similar congruence of diagnoses when we examined claims involving substance use disorders and serious mental illness. For example, 5 percent of children had a claim involving a substance use disorder; however, in families in which an adult had a claim involving a substance use disorder, 13 percent of children had a claim involving a substance use disorder. In all cases, if a family member had a specified condition, other consumers in the family were significantly more likely to file a claim for that condition (p<.01). (Data are available on request.)

Users and covered charges across families

The majority of consumers (73.8 percent) were in one-consumer families, 19.7 percent were in two-consumer families, 5 percent were in three-consumer families, and 1.5 percent were in families with four or more consumers. The data suggest that the average covered charge per consumer increased with the number of consumers in the family. The consumers in one-consumer families accounted for 67.7 percent of the total covered charges; those in two-consumer families, 22.6 percent; those in three-consumer families, 7.1 percent; and those in families with four or more consumers, 2.6 percent.

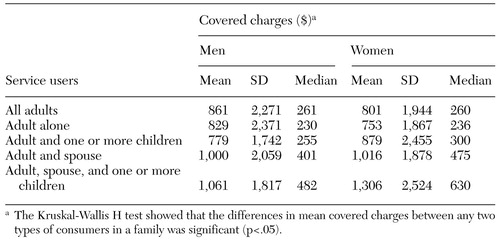

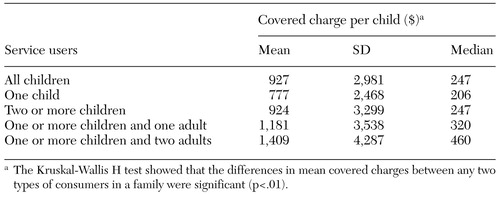

Additional data on the association between average covered charges and the number of consumers in the family are presented in Tables 4 and 5. These data show how the average covered charges for a given type of consumer—man, woman, or child—varied with the types of consumers in the family. The trends in the median covered charges are similar for all three types of consumers. In all cases, the median and mean covered charges per consumer were lowest if the consumer was the only person in the family who was using services and were highest if the consumer was living in a family in which at least one child and two adults were also using services.

We then looked at whether age, the person with the selected disorder, and intensive use varied in any systematic way with the number and type of consumers in the family. The main finding was that as the number of consumers in a family increased, those consumers were more likely to be intensive consumers and were more likely to have a claim involving a depressive disorder. For example, 25 percent of men in one-consumer families were intensive consumers of behavioral health services, compared with 39 percent of men in families in which both spouses and at least one child used behavioral health services. Similarly, 31 percent of men in one-consumer families had a claim involving a depressive disorder, compared with 41 percent of men in families in which both spouses and at least one child used behavioral health services. (Data are available on request.)

Discussion and conclusions

These data suggest that there are important interactions among family members with respect to the use of behavioral health care services. Three important observations emerge from this analysis. First, if an employee's spouse or child used behavioral health services, the probability that the employee also used behavioral health services was greater. Second, some congruence of diagnoses within multiconsumer families was noted. Third, in general, for men, women, and children, the average charge per consumer increased as the number of consumers in the family increased.

There are many reasons for possible linkages in service use among family members, such as trait preferences in spousal selection, shared genetic risks for illness between parents and children, and shared environmental risks within families, including the stress associated with the presence of an ill family member and the stress associated with divorce or an unhappy marriage (6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14). The proportion of consumers with a claim involving a mood disorder was high in multiconsumer families. In addition, consumers in these families may have similar patterns of behavioral health care use, perhaps mediated by common attitudes toward obtaining care, less influence of stigma, greater knowledge of how to gain access to behavioral health care services—including direct access to the clinicians who are providing behavioral health services to other family members—and the opportunity to learn from the positive treatment experiences of other family members.

We did not have any a priori hypotheses about how average covered charges per consumer would vary in multiconsumer families. Average covered charges would tend to be lower if a single provider was treating more than one member of a family. On the other hand, consumers in multiconsumer families may be more likely to have serious problems, which would lead to higher average covered charges. Our findings are consistent with the latter explanation. For example, in families in which both adults and at least one child used behavioral health services, 39 percent of men, 47 percent of women, and 54 percent of children were intensive behavioral health consumers, whereas the overall proportions of intensive consumers among men, women, and children were 28 percent, 27 percent, and 37 percent, respectively.

However, it is also likely that the factors that account for higher utilization rates among consumers in one family, such as shared attitudes toward obtaining care and treatment style, lead to more intensive use of behavioral health services by these consumers—this too would tend to increase average charges. Finally, covered charges may reflect billing practices: practitioners who treat more than one member of a family may shift charges from one family member to another to avoid paperwork or penalties if limits on treatment are reached. Subsequent effects of such a practice are unclear. In any case, the observed patterns are striking and should be explored in more depth with a richer database.

It is possible that information on service use patterns within families could be used to identify family members who might be at risk of mental disorders and that, within confidentiality guidelines, screening methods could be developed and implemented. It is also conceivable that such information could be used to develop case management systems or other family-directed psychosocial interventions for high-risk families. However, these data are more likely to be useful in improving care than in controlling the costs of behavioral health services, because the number of multiconsumer families is small.

Although several studies have examined interactions in mental health service use between mother and child or between parent and child (10,11,12,16,17,18), our study is one of the first to look at interactions among all consumers in a family. The study must be considered only exploratory because of four major data limitations.

First, individual eligibility data were not available. Eligibility data, which provide information on every enrollee in a health plan, are necessary for establishing detailed and complete service use patterns by family type. Second, the data we used covered only one year. Thus it was impossible to identify any temporal pattern of interaction among family members. We could observe only a one-year snapshot of what is a long-term dynamic issue and thus could look only at association, not causation. Long-term—preferably prospective —data are necessary for understanding the burden of illness within families and for developing intervention strategies. Third, the diagnostic information was based on claims data, not clinical information. Finally, although the data set was very large, it was derived from a subset of the employed population whose behavioral health care was managed by one behavioral health care company. It is not clear how representative this population is of all persons in employer-sponsored plans. Furthermore, the population that is covered by employer-sponsored health insurance is healthier and is composed of persons with higher incomes than those of other persons under the age of 65 years who are either uninsured or are covered by a public program (19,20).

Nevertheless, the data indicate that there were important interactions among family members with respect to the use of behavioral health services, and we suspect that these interactions will be important for other populations. Furthermore, the patterns of covered charges were so striking that we believe multiconsumer families should be the focus of more research. This research should focus on the nature of the clinical problems and the types of linkages between them, the clinical paradigms selected, and family attitudes toward mental health care. It is remarkable that health services research has not focused on family service use patterns.

Furthermore, the broader behavioral health research field has not invested much effort in developing empirically based family-level interventions. Although a significant movement advocated family therapy and family systems approaches for mental disorders in the 1960s and 1970s, little attention was placed on empirically studying and testing these interventions, in contrast with the attention given to individual therapies—for example, interpersonal therapy (21).

In fact, a recent review of articles published in three family therapy journals between 1994 and 1998 found few empirical studies that focused on clinical outcomes (20) and only three that reported receiving external funding (22). Our preliminary data argue for a new look at this question and for expanded and more sophisticated efforts to understand family dynamics in the use of mental health services and a focus on the family as a unit for potentially more effective and efficient interventions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant MH-56925 from the National Institute of Mental Health, grant MH-30915 from the Mental Health Intervention Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The authors acknowledge the support of Magellan Behavioral Health and Keith Roberts and Loretta Sefcovic for their assistance.

Dr. Lave, Dr. Peele, and Ms. Xu are affiliated with the Graduate School of Public Health of the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Scholle, Dr. Pincus, and Dr. Peele are with the department of psychiatry of the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Pincus is also with Rand in Pittsburgh. Send correspondence to Dr. Lave at the Graduate School of Public Health, Department of Health Services Administration, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15261 (e-mail, [email protected]). An earlier version of this paper was presented at a National Institute of Mental Health conference, "Mental Health Research: Challenges for the 21st Century," in Washington, D.C., on July 21, 2000.

|

Table 1. Use of behavioral health care services by employees whose spouses used behavioral health care services under employer-sponsored managed health plans in 1996

|

Table 2. Use of behavioral health services by employees whose children used behavioral health services under employer-sponsored managed health plans in 1996

|

Table 3. Use of behavioral health services for depressive disorders among 34,785 adult male consumers and members of their families who were covered by employersponsored managed health plans in 1996

|

Table 4. Covered charge per adult by type of behavioral health consumers in the family

|

Table 5. Covered charges per child by type of behavioral health consumers in the family

1. Cleary PD: The need and demand for mental health services, in The Future of Mental Health Services Research. Edited by Taube CA, Mechanic D, Hohmann A. DHHS pub no (ADM)89-1600. Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, 1989Google Scholar

2. Ellis RP, McGuire TG: Cost sharing and patterns of mental health care utilization. Journal of Human Resources 21:359-380, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Keeler EB, Manning WG, Wells KB: The demand for episodes of mental health services. Journal of Health Economics 7:369-392, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Olfson M, Pincus HA: Outpatient psychotherapy in the United States: I. volume, costs, and user characteristics. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1281-1288, 1994Link, Google Scholar

5. Genetics and Mental Disorders: Report of the National Institute of Mental Health's Genetics Workgroup. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1998Google Scholar

6. Garmezy N: Stressors of childhood, in Stress, Coping, and Development in Children. Edited by Garmezy N, Rutter M. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1983Google Scholar

7. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar

8. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Zhao S, et al: The 12-month prevalence and correlates of serious mental illness, in Mental Health: United States, 1996. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA. DHHS publication no (SMA)96-3098. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1996Google Scholar

9. Weissman MM: Advances in psychiatric epidemiology: rates and risks for major depression. American Journal of Public Health 77:445-451, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Farmer EMZ, Stangl DK, Burns BJ, et al: Use, persistence, and intensity: patterns of care for children's mental health across one year. Community Mental Health Journal 35:31-46, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hanson KL: Is insurance for children enough? The link between parents' and children's health care use revisited. Inquiry 35:294-302, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

12. Cunningham PJ, Freiman MP: Determinants of ambulatory mental health services use for school-age children and adolescents. Health Services Research 31:409-427, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

13. Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Rosenheck RA: The effects of marital dissolution and marital quality on health and health service use among women. Medical Care 37:858-873, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Denton WH, Reynolds DL, Burleson BR, et al: The role of marital status in health services expenditures for psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 25:383-392, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Altman BM, Cooper PF, Cunningham PJ: The case of disability in the family: impact on health care utilization and expenditures for nondisabled members. Milbank Quarterly 77 (1):39-75Google Scholar

16. Willis AG, Willis GB, Male A, et al: Mental illness and disability in the US adult population, in Mental Health, United States, 1998. DHHS pub no (SMA)99-3285. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1998Google Scholar

17. Downey G, Coyne JC: Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychological Bulletin 108:56-76, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Ping WU, Hoven CW, Bird HR, et al: Depressive and disruptive disorders and mental health service utilization in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1081-1092, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Badawi M, Kramer M, Eaton W: Use of mental health services by households in the United States. Psychiatric Services 4:376-380, 1996Google Scholar

20. Rhoades J, Chu M: Health Insurance Status of the Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population, 1999. AHRQ pub no 01-0011. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2000Google Scholar

21. Diamond GS, Serrano AC, Dickey M, et al: Current status of family based outcome and process research. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:6-16, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Hawley DR, Bailey CE, Pennick KA: A content analysis of research in family therapy journals. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 26(1):9-16, 2000Google Scholar