Predictions Made by Psychiatrists and Psychiatric Nurses of Violence by Patients

Abstract

Studies have shown that it is difficult for psychiatrists to accurately predict which patients will be violent while hospitalized. The authors compared the predictions of 14 psychiatrists and nine psychiatric nurses who independently evaluated 308 patients consecutively admitted to a hospital in Israel and rated their likelihood of becoming violent. The psychiatrists and nurses also completed a general questionnaire about the criteria they used to predict violence. No significant differences were found in the accuracy of predictions between the two professional groups or in the criteria they used to predict violence. The total predictive value, or proportion of all cases predicted correctly, was 82 percent for the psychiatrists and 84 percent for the nurses. The predictions of the two groups coincided for 83 percent of the patients. The results suggest that psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses make similarly accurate predictions of violence and use similar criteria for making them.

Accurately predicting which psychiatric patients will exhibit violent behavior has proved to be difficult, possibly because of a lack of tools for making such predictions (1,2,3,4). Predicting violence is critical for establishing a patient's need for compulsory psychiatric admission and is important in ensuring the safety of staff and patients (1). In many countries, only predictions made by psychiatrists are relevant in court proceedings, such as commitment hearings. Thus most studies of predictions of violence have focused almost exclusively on psychiatrists. As a result, little is known about how psychiatrists' predictions compare with those of other mental health professionals. In this study we compared predictions made by psychiatrists and by psychiatric nurses who independently evaluated a cohort of patients consecutively admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Israel.

Methods

The study was conducted between January and September 1999. The 14 psychiatrists and nine nurses who staffed a psychiatric hospital's emergency department were asked to rate the probability that patients admitted to the hospital would be violent during hospitalization. Probability ratings were based on a 5-point scale—0, 25 percent, 50 percent, 75 percent, or 100 percent—developed in a previous study (4). The psychiatrists and nurses were also asked to make separate ratings of the probability of violence during the first 24 hours, ten days, one month, and three months of hospitalization.

Each patient was rated by one nurse and one psychiatrist, each of whom had independently interviewed the patient, examined the patient's chart, and had various amounts of contact with the patient's significant others. Predictions were made for 308 of the 323 patients who were admitted to the emergency department during the study period.

At the end of the six-month study, all of the staff members were asked to complete a questionnaire about the criteria they had used to predict violence. They were asked to rate 21 criteria on a 5-point scale ranging from 1, not at all important, to 5, very important. These criteria were drawn from the literature and from interviews with emergency department psychiatrists who were not involved in the study. Information about incidents of violence was obtained from nursing summary reports that were routinely completed for each patient at the end of each shift. The reports, which are part of the patient's chart, record the patient's participation in activities, behavior at mealtimes, and overall behavior. Violence was defined as physical aggression toward others.

The data analysis focused on the relationship between the psychiatrists' and nurses' predictions of violence and incidents of violence and on comparing the accuracy of prediction between the two professional groups. Additional analysis compared the criteria the two groups used to predict violence. A probability rating of 50 percent, 75 percent, or 100 percent was considered to be a prediction of violence, and a rating of 0 or 25 percent was considered to be a prediction that the patient would not be violent. Patients about whom staff responded "unknown" when asked about the probability of violence were excluded from the analyses.

The accuracy of predictions was determined by comparing the predictions of violence and nonviolence with the number of actual incidents of violence, using cross-tabulations with chi square and kappa tests. A similar approach was used to make comparisons between the two professional groups.

Results

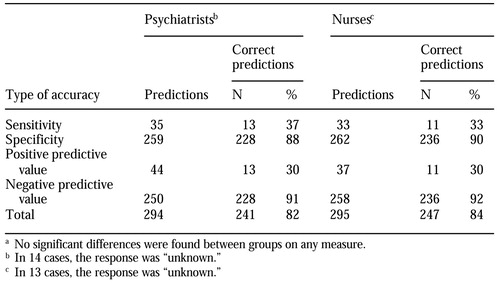

Of the 308 patients for whom predictions were made, 33 were subsequently violent. The accuracy of predictions of violence by the psychiatrists and the psychiatric nurses is summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were found in the accuracy of predictions between the two professional groups as measured by sensitivity (correctly predicting which patients would be violent), specificity (correctly predicting which patients would not be violent), positive predictive value (the likelihood of a patient's becoming violent when the clinician had predicted violence), or negative predictive value (the likelihood of a patient's not becoming violent when the clinician had predicted that the patient would not be violent).

The total predictive value—the proportion of all cases predicted correctly—was 82 percent for psychiatrists and 84 percent for psychiatric nurses. These high percentages were due primarily to the high specificity, given that most patients were not violent. The chi square test showed that the differences between the two groups were not significant. The kappa value, a measure of agreement that ranges from 0, agreement no better than would be achieved through chance, to 1, perfect agreement, showed a low level of agreement between violence predictions made by psychiatrists and nurses and incidents of violence (.23 and .22, respectively). No significant differences were found between the two professional groups in predictions of violence for the various periods of hospitalization—24 hours, ten days, one month, and three months. In an additional analysis (data not shown), we found that applying 25 percent as the cutoff point for defining a prediction of violence did not improve the overall accuracy of prediction for either group.

The predictions of the nurses and the psychiatrists coincided for 236 patients (83 percent). For the 33 patients who were violent, the predictions coincided for 24 (73 percent); for the 250 patients who were not violent, the predictions coincided for 212 (85 percent).

The rank ordering of the criteria used to make predictions was very similar between the two professional groups. Both groups rated "previous acquaintance with patient," "patient threatens violence," "verbal aggression," "rater feels threatened," and "patient damaged property" as the most important criteria, and ethnic background and gender as the least important. The rank-order correlation (r) of the two rank orders was .85, which further supports the high level of agreement between the two groups.

Discussion

We compared psychiatrists' and psychiatric nurses' predictions of violence among hospitalized patients and found essentially no differences in their predictions or in the criteria they used to make them. As in previous studies, the clinicians were better able to predict nonviolence than violence, probably because of the low base rate of violence among the patients in this study. In contrast with a previous study that was also conducted in Israel (4), in which psychiatrists succeeded in predicting nonviolence in 63 percent of cases and in predicting violence in 57 percent of cases, we found that the psychiatrists succeeded in predicting nonviolence in 88 percent of cases and in predicting violence in only 37 percent of cases.

The results of this study suggest that other professional mental health workers may be able to predict violence as accurately as psychiatrists. Future studies should compare predictions of violence among other mental health professionals. Perhaps the psychiatric nurses did as well as the psychiatrists in their predictions because of their intensive contact with patients and because, among hospital staff, nurses are the most common targets of violence (1).

One limitation of this study and similar studies is that, when violence is predicted, it is likely that the staff will take preventive actions that might successfully curtail incidents of violence and thereby negate the accuracy of their predictions. Also, it is possible that not every violent event was documented in the patients' charts (4) and that some events that occurred after the three-month follow-up might have been missed. This is an important point, because a strong association has been found between violent incidents and prolonged hospital stays (1).

Furthermore, the generalizability of the findings is limited by the small number of clinicians who participated in the study. Future research should compare predictions of violence in a larger sample of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses and should expand the study to include other types of mental health professionals, such as social workers and psychologists. In addition, the accuracy of individual predictions of violence should be compared with group predictions. Future research should also include measures of severity of violence.

The authors are affiliated with the department of social work of Bar Ilan University in Israel. Send correspondence to Dr. Rabinowitz, Chairman, Department of Social Work, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Accuracy of predictions made by 14 psychiatrists and nine psychiatric nurses of violence by patientsa

a No significant differences were found between groups on any measure

1. El-Din Soliman A, Reza H: Risk factors and correlates of violence among acutely ill adult psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 52:75-80, 2001Link, Google Scholar

2. Monahan J: The prediction of violent behavior: toward a second generation of theory and policy. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:10-15, 1984Link, Google Scholar

3. McNiel D, Binder R: Screening for risk of inpatient violence: validation of an actuarial tool. Law and Human Behavior 18:579-586, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Rabinowitz J, Garelik R: Accuracy and confidence in clinical assessment of psychiatric inpatients' risk of violence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 22:99-106, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar