Gaps in Use of Antipsychotics After Discharge by First-Admission Patients With Schizophrenia, 1989 to 1996

Abstract

The authors examined gaps in the use of antipsychotic medications during the one-year period after discharge in an epidemiological sample of 189 first-admission patients with schizophrenia between July 1989 and January 1996. Sixty-three percent of the patients had one or more such gaps, and 51 percent had gaps of 30 days or longer, with an average total time off medication of about seven months. Most gaps occurred soon after discharge, and 73 percent were initiated by the patient. These data, which were obtained before the widespread use of atypical antipsychotic agents, provide a benchmark against which to examine the impact of the newer medications on adherence and continuity of treatment in the critical early stages of schizophrenia.

The efficacy of antipsychotic medications for preventing relapses among persons who have schizophrenia has been established in randomized clinical trials (1). On the basis of findings from these studies, treatment guidelines suggest that medication regimens should be continued for at least a year after remission (2). However, nonadherence is common among these patients (3). Periods of discontinuity in medication treatment that occur early in the course of schizophrenia may have a long-term impact (4) and thus are especially critical. The available data from mixed populations or from patients with chronic illness indicate that up to 50 percent of patients with schizophrenia may be noncompliant with their medication treatment (3).

However, little information is available on the pattern of medication use among first-admission patients who are treated in usual treatment settings, especially in the United States. Results of studies from other countries suggest that treatment discontinuities due to nonadherence are at least as common in this population as they are among persons with a longer history of illness. A study from France showed that 53 percent of first-admission patients with psychosis interrupted their medication treatment against medical advice at least once during a two-year follow-up period (5). A study from Slovenia showed a 63 percent dropout rate during the first year of treatment in a group of first-episode patients with schizophrenia who were taking depot medications (6).

In this study we examined gaps in the use of antipsychotic medications during the first year after discharge from a range of treatment settings in a well-defined catchment area between July 1989 and January 1996. This period predated the widespread use of atypical antipsychotic agents, and thus our data can provide a historical benchmark for assessing the impact of newer agents and other service delivery innovations. We use the term "gap" for any discontinuation in the use of antipsychotic medication, whether initiated by the patient or by the physician.

Methods

The data were drawn from the Suffolk County (New York) Mental Health Project. The design of the project has been described in detail elsewhere (7). Briefly, first-admission patients with a psychotic disorder who were admitted to one of the 12 psychiatric facilities in Suffolk County and who met the criteria for the study and agreed to participate were recruited. The inclusion criteria were age between 15 and 60 years, residency in the county, and clinical evidence of psychosis. The exclusion criteria were a psychiatric hospitalization more than six months before the current admission, moderate or severe mental retardation, and inability to speak English.

Overall, 674 (72 percent) of the patients who met the inclusion criteria agreed to participate and were interviewed at baseline. Written informed consent was obtained after the procedures had been fully explained. After the baseline interview, participants were interviewed by telephone every three months and through face-to-face contacts after six, 24, and 48 months. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) was administered at these interviews. On the basis of information from interviews with the participants, with their relatives, and from medical records, consensus research DSM-IV diagnoses were formulated. Institutional review board approval was obtained for the study.

A total of 581 participants (84 percent) completed the 24-month follow-up interview. Of these, 189 (33 percent) had a 24-month DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia and were included in the analyses. Medication use data were recorded from available sources, including medical records, inpatient discharge summaries, and interviews with the participants or their significant others. The reliability of the participants' reports was established in a study that compared these reports with information from medical records (8). A manual with detailed guidelines for coding the medication data is available from the first author.

Results

The mean±SD age of the 189 participants was 28.8±8.9 years. Most were male (127 patients, or 68 percent), non-Hispanic white (134 patients, or 71 percent), and never married (148 patients, or 78 percent) and had an educational level of high school or above (141 patients, or 75 percent). The median delay from the appearance of the first psychotic symptoms to hospitalization was 289 days; for 85 patients (45 percent of the sample), the delay was one year or longer. At the time of the baseline interview, 83 patients (44 percent) had a lifetime SCID diagnosis of a substance use disorder. Seventy-six participants (40 percent) were discharged from state facilities, 62 (33 percent) from university-affiliated facilities, 42 (22 percent) from community facilities, and nine (5 percent) from other inpatient facilities.

According to hospital records, antipsychotic medications were not prescribed for seven of the 189 participants. The hospital diagnoses for these patients were psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (three patients), brief reactive psychosis (one patient), substance-induced delusional disorder (one patient), bipolar disorder (one patient), and schizophrenia (one patient). Since the focus of the study was on gaps in antipsychotic medication use after discharge, these seven patients were not included in the analysis.

Of the remaining 182 participants, ten did not take any antipsychotic medications during the year after discharge. Among the 172 who were using antipsychotic medications after discharge, 158 (92 percent) used conventional oral antipsychotics, 41 (24 percent) used depot agents, and 24 (14 percent) used atypical agents, with 47 (27 percent) using more than one type. For these 172 participants, the mean±SD dosage during the one-year period after discharge was 360±273 mg a day in chlorpromazine-equivalent units.

Sixty-eight (37 percent) of the 182 participants used antipsychotic medications throughout the one-year period without any gaps. Eighty-six participants (47 percent) had only one gap, and 28 (15 percent) had more than one gap. The total number of gaps was 147. Among participants with gaps, the mean±SD cumulative number of days spent without taking any antipsychotic medication was 170±125. Some of the gaps were brief: 39 lasted less than 30 days, and 15 of these lasted less than a week. For the 93 participants who had gaps of 30 days or longer, the mean±SD number of days without taking an antipsychotic medication in the one-year period was 204±112.

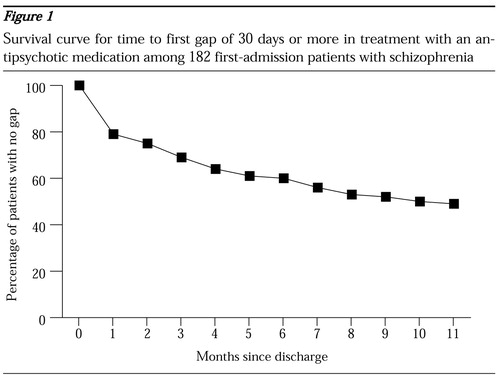

The time to the first gap of 30 days or longer is depicted in Figure 1. The upward concave shape of the survival curve indicates that the risk of gaps was higher during the earlier part of the follow-up period and declined over time. Fifty-six (60 percent) of the 93 patients who had any gaps of 30 days or longer had them during the first three months after discharge; 37 patients (40 percent) had them in the first month.

A total of 108 gaps were 30 days or longer, and information on who initiated the gap was available for 91 (84 percent) of them. Of these, 66 (73 percent) were initiated by the patient, 15 (16 percent) were initiated by the physician, and 10 (11 percent) were jointly initiated by the patient and the physician.

Discussion and conclusions

The finding of pervasive patient-initiated treatment gaps indicates that nonadherence was widespread in this group of patients. Most gaps occurred during the first few months after discharge, which points to the transition from inpatient to outpatient care as a period of high risk of discontinuation of treatment. There is some evidence that the risk of treatment discontinuation after discharge is higher among first-admission patients (9)—perhaps because they do not perceive a need to continue treatment as strongly as patients who have a longer history of illness.

Also, adverse effects of medications may be more common at the start of treatment. One of the major advantages of atypical agents is their favorable side effect profile, and there is some evidence from randomized clinical trials that the use of these medications may improve treatment continuation (10). The impact of atypical agents on continuity of treatment for first-admission patients in usual practice settings has yet to be assessed. Findings from this study may serve as a historical benchmark against which future studies may evaluate the benefits of new medication.

Our findings also highlight the need for implementation of linkage mechanisms to facilitate the transition from inpatient care to aftercare in the community (9). These strategies may involve connecting patients with aftercare services while they are still in the hospital as well as improving communication between inpatient staff and outpatient clinicians about discharge plans. Involving the patients' families in aftercare could also improve continuity of care in these critical early stages of illness.

Acknowledgments

The Suffolk County Mental Health Project is supported by grant MH-44801 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The medication chronology study is supported by a grant from Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Mojtabai's work is supported in part by grant K01-MH-01754 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression.

Dr. Mojtabai is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Columbia University and the New York State Psychiatric Institute in New York City. Ms. Lavelle, Dr. Carlson, and Dr. Bromet are with the department of psychiatry and behavioral science at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Dr. Gibson is with Eli Lilly and Company in Indianapolis. Dr. Sohler is with the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Dr. Craig is with the Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Integrated Service Network 3 in the Bronx, New York. Send correspondence to Dr. Mojtabai at 200 Haven Avenue, Apartment 6P, New York, New York 10033 (e-mail, [email protected]). An earlier version of this paper was presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held May 13-18, 2000, in Chicago.

Figure 1. Survival curve for time to first gap of 30 days or more in treatment with an antipsychotic medication among 182 first-admission patients with schizophrenia

1. Gilbert PL, Harris MJ, McAdams LA, et al: Neuroleptic withdrawal in schizophrenic patients: a review of the literature. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:173-188, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM, survey co-investigators of the PORT project: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bebbington PE: The content and context of adherence. International Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 9(suppl 5):41-50, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

4. Tandon R: In conclusion: does antipsychotic treatment modify the long-term course of schizophrenia illness? Journal of Psychiatric Research 32:251-253, 1998Google Scholar

5. Verdoux H, Legronne J, Liraud F, et al: Medication adherence in psychosis: predictors and impact on outcome: a 2-year follow-up of first-admitted subjects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 102:203-210, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Novak-Grubic V, Tavcar R: Treatment adherence in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 50:970-971, 1999Link, Google Scholar

7. Bromet EJ, Schwartz J, Fennig S, et al: The epidemiology of psychosis: the Suffolk County Mental Health Project. Schizophrenia Bulletin 18:243-255, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Gibson PJ, Lavelle J, Bromet E: Building a useful pharmacotherapy data set from multiple sources. Presented at the Annual Conference of the Association of Health Services Researchers, Chicago, June 27-29, 1999Google Scholar

9. Boyer CA, McAlpine DD, Pottick KJ, et al: Identifying risk factors and key strategies in linkage to outpatient psychiatric care. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1592-1598, 2000Link, Google Scholar

10. Rosenheck R, Chang S, Choe Y, et al: Medication continuation and compliance: a comparison of patients treated with clozapine and haloperidol. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:382-386, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar