Representative Payee Programs for Persons With Mental Illness in Illinois

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Representative payee programs can improve the community tenure of persons with mental illness by ensuring that their basic needs, such as housing, are met. The authors conducted a survey to assess the extent to which representative payee programs are provided by community mental health centers and the criteria used in enrolling clients in these services. METHODS: Community mental health centers under contract to the Illinois Department of Human Services participated in a census survey. Survey questions concerned provision of representative payee programs, service characteristics, and criteria for enrollment in the programs. RESULTS: Representative payee programs were directly provided by 59 percent of the 95 community mental health centers in the sample. More than a third of clients who were receiving intensive services had a representative payee. More than three times as many such clients had a representative payee when agencies provided representative payee programs directly rather than through referrals of family members. Frequently cited criteria for enrollment in a representative payee program included a lack of financial skills (89 percent), a lack of rent money (52 percent), substance abuse (50 percent), homelessness (33 percent), and frequent (37 percent) or long-term (30 percent) hospitalization. The majority of the representative payee programs (76 percent) provided this service to clients who received representative payee services under the mandate of the Social Security Administration. CONCLUSIONS: Given the high proportion of clients of agencies that directly provided representative payee services who were assigned to a representative payee, all community mental health centers that provide intensive services should also directly provide representative payee services in order to improve access to representative payee services.

Persons with severe mental illness often have difficulties managing their government disability payments. A lack of financial skills can cause problems in budgeting for necessities. Also, disability payments, such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI), provide a level of income that is below the poverty line (1). The primary function of representative payeeship is to help people meet their basic living needs—for example, ensuring that disability payments are used for rent.

The risk of homelessness among persons with severe mental illness is 25 to 50 percent, which is ten to 20 times higher than in the general population (2). An extensive review of 75 case management studies revealed that both assertive community treatment and intensive case management improved community tenure by increasing housing stability and decreasing hospital use (3). Stoner (4) studied 98 persons with mental illness who were homeless and who were enrolled in a representative payee program. After one year, 77 percent of these individuals reported zero days of homelessness. Although representative payee services are often provided as part of assertive community treatment programs, these studies rarely show the proportion of patients in the program who are receiving representative payee services.

The Pathways to Housing program provides further evidence of the role of representative payee programs in reducing homelessness (5). In this program, representative payee services were combined with assertive community treatment for persons in New York City who were homeless and who had dual diagnoses. Consumers were offered their choice of affordable housing with only two requirements: participation in a representative payee program and participation in meetings at least twice a month with an assertive community treatment team. In a quasi-experimental comparison, 88 percent of the program's consumers remained housed, compared with 47 percent of those who received usual services (6).

These findings were recently replicated in a controlled study in which participants were randomly assigned to the Pathways to Housing program or to usual housing services (7). The results of these studies strongly suggest that representative payee services are an effective component in the treatment of persons who are homeless, especially when combined with assertive community treatment and a respect for consumers' housing preferences. However, when the goal is prevention of homelessness among persons who are at risk of residential instability, other ways of guaranteeing access to housing may be as effective as representative payee programs (8).

The effects of representative payee services on mental health are best thought of as secondary, because these services treat psychiatric disability indirectly. For example, by helping people retain housing, representative payee programs may help decrease victimization and other aspects of homelessness that would exacerbate symptoms. The effect of these services on hospitalization rates is a concrete indicator of their effect on mental health. In a retrospective study of persons with mental illness who received representative payee services, we found a ninefold decrease in the number of days clients spent in state hospitals, from 68 at baseline to seven in the year that a representative payee was provided (p<.001) (9).

Other benefits to clients include greater cooperation with treatment and lower rates of arrest and victimization (4). Also, although client satisfaction with representative payee services may initially be low, it is likely to grow over time (10).

Thus representative payee programs seem to provide important benefits to clients. However, only one survey—in the state of Washington—has examined the nature of these programs and the extent to which they are provided in the community (11). Also, guidelines are needed for deciding which clients really need a representative payee. Because this service can play such an important role, we conducted a survey to assess the extent to which representative payee programs were provided in Illinois, the characteristics of these programs, and the criteria used for enrolling clients in the programs.

Methods

Between 1997 and 1999, we conducted a mail survey of all 219 mental health service programs that were under contract to the Illinois Department of Human Services in 1996. The surveys were addressed to the directors of the programs, with a request that they be forwarded to the staff who were most knowledgeable about representative payee services. After a follow-up telephone survey, 57 programs were excluded because they were not mental health centers that provided direct service in the community, were not serving adults with mental illness, or were duplicates of listed programs. The 162 remaining community mental health centers had programs that served persons with mental illness as well as developmentally delayed persons, programs whose primary service population was individuals with mental illness, and four programs whose service population could not be determined.

Of the 158 community mental health centers whose client population included persons with mental illness, 111 (70 percent) responded to the survey. Because the focus of the study was provision of services for individuals with mental illness, a subgroup of programs that served a substantial proportion of persons with mental illness was selected. Programs were selected for further analysis if 25 percent or more of their clients had a mental illness. Within this group of 141 agencies, 95 (67 percent) responded.

Survey questions concerned whether representative payee services were provided directly by the agency, the proportion of clients served, the characteristics of the representative payee program, and what type of staff provided the service. Respondents were also asked to indicate what criteria the agency used to determine which clients should receive representative payee services. A checklist was provided for this question, based on findings from a chart review in our earlier study (9). Because of the high incidence of comorbid substance dependence among persons with severe mental illness, additional questions were asked about the role of the representative payee in dealing with substance use problems (12,13).

The respondents were asked about the extent to which payees linked clients' access to discretionary funds to substance use, treatment adherence, money management skills, and functional level. As in an earlier survey (11), possible responses ranged from 1, not at all linked, to 5, linked to a high degree. Respondents were asked what the representative payee did if the client was using substances to the point of abuse or dependence. Possible answers to this question were "take no action" and "reduce access to discretionary money."

Means and frequency distributions were used to describe the characteristics of representative payee service provision; t tests were used to examine the differences between agencies that provided representative payee services directly and those that relied on family members and referrals for representative payee services, particularly for services to clients who were receiving intensive treatment. The statistical package SPSS 10 was used for the analyses (14).

Results

Representative payee services were directly provided by 56 (59 percent) of the 95 community mental health centers at which at least 25 percent of the service population had a mental illness. Clinicians functioned as representative payees in a majority of the programs (43 programs, or 76 percent). Seventeen (30 percent) of the centers that provided representative payee services used a centralized system of tracking and disbursing clients' funds. Funds were also distributed by caseworkers (28 programs, or 50 percent) or treatment teams (17 programs, or 30 percent) and occasionally through the mail (15 programs, or 27 percent). Agencies that provided representative payee services directly did not differ from other agencies in structural factors, such as the size of their intensive treatment program.

Because we believed that clients who were receiving intensive treatment services were most in need of representative payee services, we asked the staff of the community mental health centers how many of these clients they served. Intensive services were described as including, for example, assertive community treatment, supportive housing, or residential extended care. The mean± SD number of clients who received intensive treatment was 82±183. More than a third (36 percent) of the clients who received intensive services had some form of representative payee.

However, among mental health centers that provided representative payee services directly, clients who were receiving intensive treatment were more than three times as likely to have a representative payee as clients of centers that relied on friends and family members or used referrals for this service (47 percent compared with 14 percent, t=4.525, df=56, p<.001). The majority of the agencies (76 percent) reported that clients who received representative payee services did so under the mandate of the Social Security Administration (SSA).

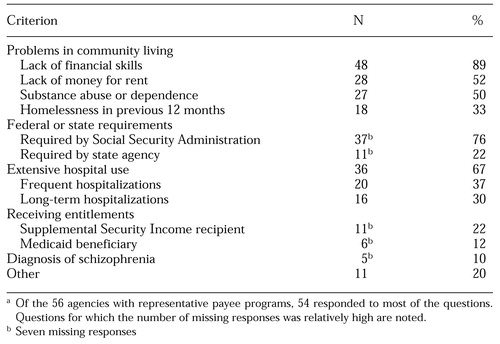

Respondents were asked to describe their criteria for determining which clients should receive representative payee services; their responses are summarized in Table 1. Problems in managing community living were the most frequently mentioned criteria—lack of financial skills, lack of rent money, and substance abuse or dependence. Other important factors included requirements by government agencies, such as the SSA or a state agency, and extensive hospital use. Psychiatric diagnosis was rated as far less important than functional impairment—only a tenth of the respondents reported that a diagnosis of schizophrenia was considered when clients were enrolled in representative payee programs.

Representative payee services were characterized by active involvement in helping the client with daily needs. Among the agencies that acted as representative payees, all enrolled the client in the representative payee program, developed the client's budget, and paid rent and other bills directly. Most agencies also assessed the client for representative payee services (51 agencies, or 93 percent) and helped with grocery shopping (52 agencies, or 98 percent) and transportation (42 agencies, or 89 percent). Counseling on money management was a key component of the representative payee programs of all the agencies. Perhaps as a consequence of these counseling efforts, the agencies reported that relatively few clients (21 percent) had disagreements with the payee about the client's money.

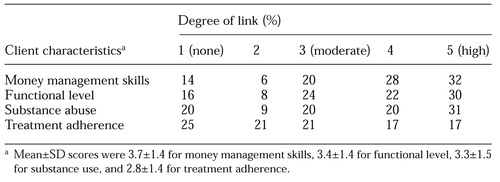

An important issue concerns the extent to which various client characteristics were linked with clients' access to discretionary funds—that is, funds that remained after expenses for necessities had been paid. As shown in Table 2, payees were most likely to grant greater access to discretionary funds to clients who had higher levels of functioning, particularly those with better money management skills. Most payees (32 programs, or 71 percent) made access to funds at least moderately contingent on improvements in substance use problems. Twenty-nine (62 percent) of the representative payee programs reduced access to discretionary money when clients were using substances to the point of abuse or dependence. Although access to funds was not as often contingent on adherence to treatment, it was at least moderately linked by more than half of the representative payee programs (26 programs, or 55 percent).

Discussion

Although a majority of the community mental health centers in Illinois provided representative payee services, a substantial proportion (41 percent) did not. Also, relatively few clients who received intensive services had some form of representative payee (36 percent), yet such clients are likely to have a strong need for help in managing their money because of the severity of their disabilities. The proportion of these clients who received representative payee services was more than three times higher (48 percent compared with 14 percent) when the agency provided representative payee services directly.

Research suggests that representative payee programs are beneficial to clients. Thus it is puzzling that more agencies do not provide this service for clients who have serious mental illness. There are several possible reasons for this apparent service gap. Agencies and clinicians may prefer that clients choose a representative payee from their family or other members of their informal support network. Other possible reasons are ambivalence about mandating representative payee services and concerns about conflicts in the therapeutic relationship (15).

For persons with physical disabilities, family members are appointed as representative payees in the vast majority of cases (85 percent) (16). However, it is generally more difficult to find appropriate and responsible family members to act as representative payees for adults with mental illness than it is for adults with other types of disabilities. This difficulty is due to several factors, including disconnection from the family in this population and occasional misuse or theft of the clients' money by family representative payees. Some clients can be abusive and even violent toward family members over issues such as use of disability payments to buy drugs.

To address these problems, Congress and the Social Security Administration have worked in recent years to broaden the range of noncustodial agencies that can act as representative payees, including community mental health centers (17). Ideally, the selection of a representative payee coincides with the client's preference. However, when no appropriate representative payee can be found in the client's informal support network, it is important for agency payees to be available.

In our survey, a majority of representative payee programs (76 percent) provided this service to clients who received representative payee services under the mandate of SSA. However, we previously found that even when SSA mandated 80 percent of clients to representative payees, clinicians believed that most clients had chosen the service voluntarily (9). This misconception may have been due to ambivalence among clinicians about the ethics of working with clients who have reduced autonomy. As we have noted, there is a growing body of evidence that representative payee programs are beneficial to clients. Beneficence and autonomy are the two core principles underlying ethical judgments (9). If persons with severe disabilities are at risk of harm as a result of their inability to use disability payments to meet their basic needs, the ethical obligation to protect a client's welfare may override the client's right to self-determination (18).

Fear of introducing conflicts into the therapeutic relationship may also account for case managers' reluctance to endorse and provide mandated representative payee services. Respondents to our survey reported that disagreements about money management occurred between payees and about a fifth of their clients.

In a related finding in another study, about the same proportion of case managers reported that serving the representative payee function disrupted the therapeutic relationship (10). In that study, a minority of clients (20 percent) affirmed the statement "I can't talk to my therapist about my feelings because he or she controls my funds." However, most clients reported that the positive effects of having a representative payee included helping them make their money last all month (88 percent), learn budgeting skills (80 percent), maintain their housing (78 percent), and control their drug or alcohol abuse (80 percent). The authors concluded that, overall, having case managers act as representative payees does not appear to seriously disrupt the therapeutic relationship.

Obviously the decision to mandate representative payee services should not be made lightly. The results of our survey suggested indicators for referral to a representative payee program, including deficits in skills that are essential to community living, such as financial skills and the ability to budget for rent money; substance abuse or dependence; homelessness; and frequent or long-term hospitalization. Mandates by SSA and state agencies were also found to be an important influence on the provision of representative payee services. To the extent that SSA required that clients meet specific criteria for such mandates, there is an overlap between SSA criteria and these indicators. The Illinois Office of Mental Health also influenced agency programs by requiring that representative payee services be available for clients receiving assertive community treatment. Finally, consistent with SSA guidelines, relatively few agencies relied on diagnostic criteria, which stress functional impairment over diagnosis.

Similar indicators of the need for a representative payee were found in a chart review of clients who were receiving representative payee services (9). In another study, clients of a representative payee program were compared with clients from the same agency who were not referred to the representative payee program (19). Again, factors associated with referral included lack of rent money, lack of financial skills, homelessness, and extensive hospital use. Persons with severe and persistent mental illness were also more likely to be referred to representative payee services. Surprisingly, those who were referred were as likely as those who were not referred to have problems with substance abuse or dependence, which suggests a need to more closely examine factors such as the severity of the substance use problem.

Rosen and Rosenheck (20) proposed that a representative payee is indicated if substance use is severe enough to cause "clinically significant impairment or distress" and if it is the cause of "substantial harm to the recipient, victimization of the recipient, or unavailability of funds to meet basic needs." As in the survey in Washington State (11), our survey showed frequent use of contingency management, such as linking access to discretionary funds to the client's willingness to deal with substance use problems. Although the effectiveness of contingency management has been examined among persons with substance use problems (21), there is little evidence of the effectiveness of this method among persons who are also mentally ill (22).

Conclusions

The results of our survey suggest that the use of representative payee services is low when community agencies are not available to provide these services directly for their clients. Yet it appears that representative payee services are an essential component of effective programs for clients who need intensive services. It could be argued that to increase access to representative payee services, all community mental health centers that provide intensive services should also directly provide representative payee services. Despite difficulties in developing and maintaining a representative payee program, such programs should be part of the array of services available for persons who have serious mental illness.

Another important factor is that for a majority of the representative payee clients in Illinois these services are mandated by federal and state regulations, which suggests that a reduction in autonomy occurs frequently in this population. Finally, additional work is needed to clarify clinical criteria for qualifying for representative payee services as a result of substance abuse.

Dr. Hanrahan, Dr. Luchins, Ms. Savage, and Ms. Patrick are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the University of Chicago and with the Illinois Office of Mental Health. Mr. Roberts is with the department of psychiatry of the University of Chicago. Dr. Conrad is with the School of Public Health of the University of Illinois at Chicago. Send correspondence to Dr. Hanrahan at the University of Chicago, Department of Psychiatry, MC3077, 5841 South Maryland Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60637 (e-mail, [email protected]). A version of this paper was presented at the Institute on Psychiatric Services held October 29 to November 2, 1999, in New Orleans and at the Annual Conference of the American Public Health Association held November 7-11, 1999, in Chicago.

|

Table 1. Criteria used by community mental health centers for enrolling clients in representative payee programsa

a Of the 56 agencies with representative payee programs, 54 responded to most of the questionsQuestions for which the number of missing responses was relatively high are noted.

|

Table 2. Agency ratings of the extent to which the representative payee program links client characteristics and access to discretionary

1. Watson A, Hanrahan P, Luchins DJ, et al: Paths to jail among mentally ill persons: service needs and service characteristics. Psychiatric Annals 31:421-429, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, et al: Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a "critical time" intervention after discharge from a shelter. American Journal of Public Health 87:256-263, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37-74, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Stoner MR: Money management services for the homeless mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:751-753, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Tsemberis S, Asmussen S: From streets to homes: the Pathways to Housing consumer preference supported housing model, in Homelessness Prevention in Treatment of Substance Abuse and Mental Illness: Logic Models and Implementation of Eight American Projects. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 17. Edited by Conrad KJ, Matters MD, Hanrahan P, et al. New York, Haworth, 1999Google Scholar

6. Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF: Pathways to Housing: supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 51:487-493, 2000Link, Google Scholar

7. Tsemberis S, Shinn B, Moran L, et al: Pathways to Housing: a consumer preference supported housing model. Presented at the Steering Committee Meeting of the SAMHSA Collaborative Program to Prevent Homelessness, Washington, DC, October 12-13, 2000Google Scholar

8. Conrad KJ, Matters MD, Hanrahan P, et al: Representative Payee for Individuals With Severe Mental Illness at Community Counseling Centers of Chicago: Final Report to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Chicago, University of Illinois, 2001Google Scholar

9. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Conrad KJ, et al: An agency-based representative payee program and improved community tenure of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:1218-1222, 1998Link, Google Scholar

10. Dixon L, Turner J, Krauss N, et al: Case managers' and clients' perspectives on a representative payee program. Psychiatric Services 50:781-786, 1999Link, Google Scholar

11. Ries RK, Dyck DG: Representative payee practices of community mental health centers in Washington State. Psychiatric Services 48:811-814, 1997Link, Google Scholar

12. Appleby L, Luchins DJ, Dyson V: Effects of mandatory drug screens on substance use diagnosis in a mental hospital population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:183-184, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 264:2511-2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. SPSS, version 10.0. Chicago, SPSS, Inc, 2001Google Scholar

15. Brotman AW, Muller JT: The therapist as representative payee. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:167-171, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Cogswell SH: Entitlements, payees, and coercion, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment: A New Frontier in Mental Health Law. Edited by Dennis D, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

17. Final Report of the Representative Payment Advisory Committee. Washington, DC, Social Security Administration, 1996Google Scholar

18. Abramson M: Autonomy vs paternalistic beneficence: practice strategies. Social Casework 70:101-105, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Conrad KJ, Matters MD, Hanrahan P, et al: Describing patients with mental illness in a representative payee program. Psychiatric Services 49:1223-1225, 1998Link, Google Scholar

20. Rosen MI, Rosenheck R: Substance use and assignment of representative payees. Psychiatric Services 50:95-99, 1999Link, Google Scholar

21. Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, et al: Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:568-576, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Shaner A, Roberts LJ, Eckman TA, et al: Monetary reinforcement of abstinence from cocaine among mentally ill patients with cocaine dependence. Psychiatric Services 48:807-810, 1997Link, Google Scholar