Best Practices: New York State's Campaign to Implement Evidence-Based Practices for People With Serious Mental Disorders

As a recent report from the Institute of Medicine so vividly highlights, America's health care system has widespread gaps between what science has proved to be optimal treatment and the care that is routinely delivered in most health care settings (1). Failure to embrace evidence-based practices for persons who have serious mental disorders is also a recurring theme in the literature (2).

Core set of evidence-based practices

Evidence-based interventions are grounded in consistent research findings (3). In fact, a core set of practices that have been found to be efficacious, and in many cases also effective, has been identified (4). These core practices include medications, training in illness self-management, assertive community treatment, family psychoeducation, supported employment, and integrated treatment for co-occurring substance use disorders.

In its priority set of evidence-based practices for adults, New York State has added self-help and peer-support education and treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A close inspection of the literature indicates that self-help services may be more than just promising as an example of evidence-based practice, albeit in the domain of complementary care (5,6). Self-help is a lifelong support that has been proved beneficial to the sustained management of many health conditions (7,8,9). There is a growing body of evidence in relation to the treatment of PTSD (10). In response to the catastrophic events of September 11, New York State has looked to the research for the most effective treatments.

Changing the environment

The challenge in implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health settings is largely to create a major shift in how the mental health industry defines a high-quality environment. A high-quality system must be based on research evidence and must also be consumer-centric, representing a shift in goals from community-based systems of care that treat and shelter or support consumers to community-integrated systems that deliver high-quality services to customers who want to design and manage their own recovery.

Recovery is complex and multidimensional, involving relationships among symptoms, self-concept, and social outcomes (5). Adults who have severe mental illness say that their most important goals are related to work, housing, interpersonal relationships, and education (11). These goals are all important to the integration of individuals into mainstream patterns of social functioning.

Thus recovery can never be viewed simply as a metaphor for the alleviation of symptoms. This fact is central to understanding and valuing shifts toward science-based practice in the creation of an environment of change for both providers and consumers. Evidence-based practices support recovery by providing practitioners with proven tools that can help individuals obtain relief from disabling symptoms and achieve the important goals of recovery.

Facing the challenges

State mental health authorities will face many challenges in their planning efforts to systematically implement statewide evidence-based practices. New York state mental health executives convened a panel of experts at a June 2001 gathering to provide input to New York's implementation plan. These experts shared their perspectives on several challenging areas: communicating a vision, applying research to real-world settings, reaching consensus and increasing the likelihood of support for evidence-based practices, using outcomes data, integrating cultural competence, and incorporating the perspectives of the recipient and his or her family. Key emerging themes are discussed in the following sections.

Communicating a vision to obtain support. One of the first challenges is how best to communicate a vision needed to obtain support for change. Credibility on the part of mental health authorities is essential in obtaining ongoing support for a shared vision of change. Credibility shapes relationships with various constituency groups, and each group needs to be treated fairly and to have an input in decision making and shaping the future.

State mental health authorities must also have credibility within the hierarchy of their own state governments in order to facilitate the necessary shifts in commitments and resources. The public's trust must be earned. Mental health authorities need to visibly balance high-quality effective care with public safety while educating the public about current science and recovery.

Applying research to real-world settings. The best outcomes are achieved when evidence-based practices are made available to recipients in combination and when accountability for the coordination of delivery is fixed at the local government level. In New York State this approach to delivery is being achieved in a number of ways, including the growth of assertive community treatment and case management, the provision of housing, the creation of single points of access to these services, and the expansion of flexible, mobile, and wraparound services for children.

A second strategy is to embed the use of evidence-based practices into regulations and to incorporate methods for assessing the presence or absence of evidence-based practices into protocols for licensing site visits. The first statewide evidence-based licensing protocol is being used for assertive community treatment.

Reaching consensus about evidence-based practices. The consensus of experts plays an essential role in the promotion of evidence-based practices. Once guidelines are recommended for use, evaluative mechanisms must be developed to assess whether the guidelines actually lead to better outcomes.

Two further organizational strategies for change include incorporating knowledge and training in evidence-based practices into workforce performance standards and into academic study programs. The systemwide use of evidence-based practices calls for modifying the behavior of many clinicians. Widespread dissemination of research findings that demonstrate the effectiveness of interventions is needed, as is the widespread availability of technical assistance. Multi-pronged approaches, particularly with sustained interaction and hands-on practice, are most likely to lead to behavioral change.

Educational efforts directed at and tailored to service recipients and their families are also needed. If successful, such efforts will yield demand from stakeholders for services that have been proven effective. Having champions of implementation of evidence-based practices across all stakeholders is critical.

Demonstrating systemwide effectiveness. To understand what services and treatments work best and for whom, and to build public support for new investments in services, it is essential that data on outcomes be measured and the results reported and used to inform decision making.

New York State's strategy integrates an information system infrastructure that is accessible to state and local mental health authorities and allows for rapid ad hoc querying of an expanding array of service use, financial, planning, and outcomes data; a modular measurement approach that incorporates the performance areas of access to services, support for recovery and the impact of service delivery, and recipient self-report measures of wellness and community integration; report cards designed to capture outcomes that are tailored to the needs and interests of key stakeholders; and new protocols for licensing and certification that document fidelity to evidence-based practice models.

Integrating cultural competence. Once a person is engaged in treatment, the system's ability to maintain contact through respectful treatment is critical to the achievement of positive outcomes. It is necessary to understand the different service populations and to meet their various language needs. Linkages with varied communities must be developed and nurtured. In addition, behaviors learned through cultural experience are often misinterpreted. When data are gathered, samples must be truly representative of the patients served and must include significant numbers of persons from multicultural communities.

Consumer demand. It is important that consumer groups generate a grassroots demand for evidence-based services by increasing advocacy efforts at the state and local levels and by calling for greater consumer involvement in service delivery.

Recipients and their families have a powerful motivation to press for changes that will make mental health systems truly focused on recovery. The National Alliance for the Mentally Ill has demonstrated in many states that family-based advocacy can result in new programs and funding streams and has proved that it is possible to generate demand for evidence-based services and improved performance.

Strategies for change

State mental health authorities have the greatest potential and power to influence change to improve mental health care so that it routinely offers the best interventions that have been proven by scientific research. Assuming that implementing an evidence-based practice agenda will raise the quality-of-care bar, mental health leaders must take this calculated risk.

Focused group discussions with key stakeholders across the state of New York have indicated that both cultural and structural change will be needed. Cultural change is needed for creating an organization that is dedicated to continuous learning and quality improvement, creating widespread belief in the possibility of recovery, and understanding and valuing shifts toward science-based practice. Structural change is needed to improve contracting and regulations and workforce supports for education and supervision and to develop uniform standards and procedures for assessment, service planning, and outcomes management.

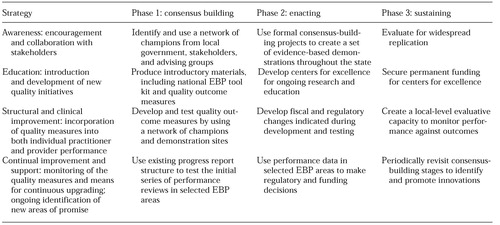

New York's model for enacting such change is outlined in Table 1. Four primary change strategies have been identified: awareness building among stakeholders, education about new quality initiatives, structural and clinical improvement that results in incorporation of quality measures into practice, and continual improvement and support that monitors quality measures while providing for continuous upgrading. These changes will be implemented in three phases: consensus building, such as building a champion network; enacting, such as introducing evidence-based toolkits; and sustaining, such as instituting permanent centers of excellence for ongoing research.

Conclusions

To achieve a better quality of mental health care, state mental health authorities will have to pursue a multi-pronged longitudinal strategy that promotes services that have proven efficacy and effectiveness. Such a strategy must incorporate consensus building, stakeholder education, clinician training, and outcomes measurement as well as financial components. Mental health authorities must look to ensure that the dollars follow mental health practices that have a strong evidence base, and they must be courageous enough to shift resources away from ineffective practices and toward practices that have an evidence base.

In addition, clinical practices that are perceived to be useful but for which there is no research base must be studied, and the pace of development of new treatments must increase. An informed consumer is our best customer. Thus consumers and families need to understand how evidence-based practices can promote rehabilitation that leads to recovery, and providers need to understand how evidence-based practices can lead to a better quality of mental health care and to improved outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ron Manderscheid, Ph.D., Robert Drake, M.D., Ph.D., Kim Mueser, Ph.D., John Oldham, M.D., Peter Jensen, M.D., Cathy Cave, Ed Knight, Ph.D., Laurie Flynn, Tom Trabin, Ph.D., Jeannie Straussman, C.S.W., and Jill Daniels.

The authors are affiliated with the New York State Office of Mental Health, 44 Holland Avenue, Albany, New York 12229 (e-mail, [email protected]). William M. Glazer, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. New York State's strategies for enacting change in implementation evidence-based practices (EBPs)

1. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2001Google Scholar

2. Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services 52:179-182, 2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: At issue: translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar

5. Carpinello SE, Knight EL, Markowitz FE, et al: The development of the mental health confidence sale: a measure of self-efficacy in individuals diagnosed with mental disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 23:236-242, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Measuring empowerment in client-run self-help agencies. Community Mental Health Journal 31:215-227, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Borkman TJ: A selected look at self-help groups in the United States. Health and Social Care in the Community 5:357-364, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Kurtz LF: Self-Help and Support Groups: A Handbook for Practitioners. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1997Google Scholar

9. Vogel HS, Knight E, Laudet AB, et al: Double Trouble in Recovery: self-help for people with dual diagnoses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21:356-362, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Friedman M: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: The Latest Assessment in Treatment Strategies. Compact Clinical Publishing, 2000Google Scholar

11. Felton C, Stasney P, Shern DI, et al: Consumers as peer specialists on intensive case management teams: impact on client outcomes. Psychiatric Services 46:1037-1044, 1995Link, Google Scholar