An Analysis of Cue Reactivity Among Persons With and Without Schizophrenia Who Are Addicted to Cocaine

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Persons with schizophrenia who are addicted to cocaine experience more psychiatric and substance abuse relapses and worse long-term outcomes than persons with only one of these conditions. This study examined whether individuals with cocaine dependence and schizophrenia experience more cue-elicited craving than those without schizophrenia. METHODS: Ninety-one cocaine-dependent participants who had been abstinent from cocaine for at least 72 hours were recruited from substance abuse treatment programs in the Veterans Affairs New Jersey Health Care System. The study used a cue-exposure paradigm to stimulate cocaine craving. A self-report instrument was used to measure changes from baseline in four areas: craving intensity, happy or depressed mood, increased or decreased energy, and physical health or sickness. RESULTS: The participants with schizophrenia (N=35) reported significantly more cocaine craving than those without schizophrenia (N=56). When data for participants who were cue reactive were analyzed without regard to diagnosis, 97 percent of the cocaine-dependent participants with schizophrenia were cue reactive, compared with 43 percent of those without schizophrenia. CONCLUSIONS: Future research on cocaine dependence should focus on craving, particularly among patients with coexisting psychiatric disorders.

Cocaine is an illicit drug that has powerful reinforcing properties (1,2) and that is commonly abused by individuals with schizophrenia (3). Although a great deal of research has been done on craving among persons addicted to cocaine who do not have schizophrenia, few studies of craving have focused on individuals with a dual diagnosis of schizophrenia and cocaine dependence. Carol and colleagues (4) recently compared retrospective self-reported cocaine craving among persons with and without schizophrenia who were addicted to cocaine and used a repeated-measures design to examine state stability. The results suggested that those with schizophrenia and cocaine dependence had significantly more craving; the level of craving remained high at a 72-hour follow-up examination.

The use of retrospective self-report for studying cocaine craving has three major limitations. First, craving is an inducible state that is highly responsive to drug-related stimuli. A lack of exposure to these stimuli may artificially reduce the intensity of craving (5). Second, a retrospective design prevents addicted persons from being exposed to a common set of drug-related events at the time of the rating. For example, although two individuals may be highly responsive to environmental drug cues, one may recall a situation that is only moderately evocative and the other may recall a situation that is highly evocative. The third major limitation deals with the process and the accuracy of recall. When the addicted person is asked to accurately recall a previously induced uncomfortable internal state, such recall is extremely vulnerable to cognitive distortions (6). Exposing an individual to a common broad-based set of cues controls for the problem of recall and may eliminate some of the individual differences in reactivity to particular cues.

Cue exposure offers a unique paradigm to systematically present patients with cocaine cues in a laboratory in order to study this provoked craving state (7). A large body of research has accumulated over the years to suggest that cue exposure is a reliable method for studying craving among patients with the single diagnosis of cocaine dependence (7,8). The most common modalities used in cue-exposure research protocols are videotapes and handling of drug paraphernalia, although other protocols have also incorporated audiotaped cues (9). These stimuli have been reported to increase drug craving and physiological arousal as shown by measures of skin conductance, skin temperature, heart rate, and respiration (7,8,10).

An interesting phenomenon reported in the cue-exposure literature is that about half of cocaine-dependent patients without schizophrenia do not show an increase in craving intensity after being exposed to cocaine cues. To investigate this further, Avants and coworkers (11) examined the relationship between aversion to drug cues and nonreactivity but did not find a significant correlation. Others have looked for a biological explanation for the difference between responders to drug cues and nonresponders. Neuroimaging technology has been used to identify cortical changes after exposure to cues. These studies have shown activation in the cortical and limbic regions, amygdala, anterior cingulate, temporal poles, interior cingulate, and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of the brains of cocaine-dependent patients (12,13,14), and these are regions that are rich in dopamine neurons. The electroretinogram provides a physiological recording of the blue cone b wave amplitude in the retina. Because an abnormal blue cone b wave amplitude is found on electroretinograms of individuals with dopamine system disorders such as cocaine dependence, it has been used to explore the cue-reactivity phenomenon (15,16). These studies showed that persons with a reduced electroretinogram amplitude response had significantly more cue-elicited craving.

In addition to the dopamine system's mediation of craving, a great deal of research suggests that the dopamine system mediates the symptoms of schizophrenia (17,18). For this reason, comparing cue reactivity among cocaine-dependent individuals with and without schizophrenia is a naturalistic way to examine the influence of dopamine.

The results of this comparison will advance our understanding of cocaine craving among persons with schizophrenia and cocaine dependence. They will also help us determine whether this high-risk population is more vulnerable to drug cues and therefore in need of specialized treatments designed to reduce the craving state. We hypothesized that persons who have both schizophrenia and cocaine dependence would report significantly more craving and a higher percentage of cue reactivity than cocaine-dependent persons who do not have schizophrenia.

Methods

Study sample

We obtained institutional review board approval to conduct the study and then recruited 35 cocaine-dependent outpatients who had schizophrenia and 56 cocaine-dependent males who had been treated and were no longer using cocaine. The former group were recruited from the mental illness-chemical abuse programs at three campuses of the Veterans Affairs New Jersey Health Care System—the Newark, Lyons, and East Orange campuses—and the latter group were in the substance abuse outpatient treatment program of the same VA system.

Individuals who were included met DSM-IV criteria for cocaine dependence, which was determined independently by a doctoral-level psychologist and the first author; they reported using at least six grams of cocaine a month and had been abstinent from cocaine for at least 72 hours. Exclusion criteria were a history of opiate, barbiturate, benzodiazapine, or marijuana dependence and meeting DSM-IV criteria for another axis I disorder. For the group without schizophrenia another exclusion criterion was taking prescribed medication that could affect the central nervous system.

The data for the study were collected between 1998 and 2000. After giving written informed consent, all patients completed a brief cocaine history questionnaire developed at the National Institute of Drug Abuse Intramural Program in Baltimore. Patients also completed the within-session Voris Cocaine Craving Questionnaire (VCCQ), which is a four-item, self-report, 50-point visual analogue scale that has good reliability and validity with cocaine-dependent persons without schizophrenia (5,19). The VCCQ was included because of its ease of use and our recent positive experiences with this instrument in a similar study that examined craving among cocaine-dependent individuals with schizophrenia (4). The VCCQ measures changes on the following four scale items: craving intensity, happy or depressed mood, increased or decreased energy, and physical health or feeling sick.

We conducted the cue-exposure procedure immediately after the participant completed the initial baseline assessment instruments. During the cue-exposure procedure, the participant was seated in a comfortable chair in the laboratory and was shown a two-minute videotape of people administering intravenous cocaine followed by a two-minute videotape of people smoking cocaine. Previous research has shown that these cues elicit craving for cocaine (15,20). After watching the videotapes, participants were again asked to complete the VCCQ. Cocaine abstinence was ascertained by self-report and urine toxicology screens, which were administered randomly to assess compliance during treatment.

In the statistical analysis, independent-sample t tests were used to examine group differences in cocaine craving and delta change scores (that is, changes in craving from baseline). We also classified patients as responders and nonresponders and used a chi square test to examine differences in cue reactivity.

Results

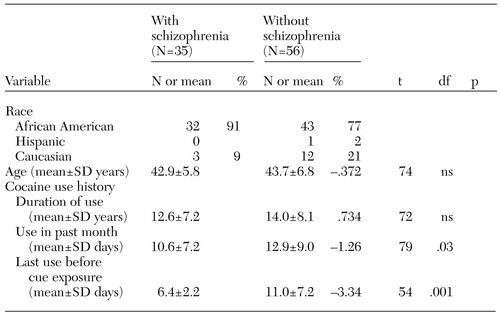

Table 1 shows the demographic differences between the groups. The cocaine-dependent participants with schizophrenia had more recent cocaine use before the cue-exposure procedure. The cocaine-dependent participants without schizophrenia had a history of heavier use and had used cocaine on more days in the month before entering the study. The major clinical difference between the groups was in psychiatric diagnoses.

Participants in both groups were compared for differences in baseline craving on the four components of the VCCQ before they underwent the cue-exposure procedure. At baseline, the 56 participants without schizophrenia had significantly higher scores on the craving intensity dimension than the 35 participants with schizophrenia (mean±SD=24.05±17.8 compared with 13.8±11.9; t=−3.3, df=89, p<.001), although there were no differences on the other craving dimensions. After cue exposure, the participants with schizophrenia showed significantly more cue reactivity on the craving intensity component than those without schizophrenia (mean= −15.8±9.2 compared with −0.14± 12.3; t=−6.8, df=89, p<.001). No significant differences were seen on the depression, energy, or sickness components of the scale as measured by a two-tailed test of significance.

We also divided the participants with schizophrenia and those without schizophrenia into a cue-reactive group and a cue-nonreactive group. We rated individuals as cue reactive if they showed any increase in craving after the cue-exposure procedure. We rated individuals as cue nonreactive if they showed no change in craving or a decrease in craving after the cue-exposure procedure. Only 24 (43 percent) of the participants without schizophrenia were cue reactive, whereas 34 (97 percent) of those with schizophrenia showed an increase in craving after the cue-exposure procedure. This difference was statistically significant (χ2=27.4, df =1, p<.001).

To control for the possibility that study participants with schizophrenia might be reactive to visual cues regardless of their history of drug abuse, we administered cue exposure to ten individuals who had schizophrenia but no history of substance abuse. None of these individuals were cue reactive, which suggested that the cocaine-dependent individuals with schizophrenia were responding to the drug content of the videotapes rather than to the visual stimulation procedure.

Discussion and conclusions

We confirmed our hypothesis that among persons with cocaine dependence, those who have schizophrenia report more craving after exposure to videotaped cocaine cues than those who do not have schizophrenia. We also found a significantly higher percentage of responders to drug cues among study participants with schizophrenia. These findings emerged despite the fact that the participants without schizophrenia had used cocaine for more days in the past month, reported a longer history of cocaine use, and had higher baseline scores on the retrospective measure of craving. However, the individuals with schizophrenia had used cocaine more recently before entering the study.

One possible explanation for the lower baseline craving among the individuals with cocaine dependence and schizophrenia may be related to their lighter use in the month before the cue-exposure procedure. However, it is equally possible that the lower baseline retrospective craving among the participants with schizophrenia may be related to the dopamine-antagonist medication that they take for the treatment of schizophrenia. Previous research on persons addicted to cocaine has shown that dopamine antagonists reduce craving among those with schizophrenia and those without schizophrenia (21,22,23,20). Although dopamine agonists may be very useful in reducing non-cue-induced self-reported craving, their efficacy may decline when craving reaches a higher threshold immediately after exposure to drug cues. However, it is also noteworthy that a small body of literature suggests that dopamine-antagonist medications may actually cause a hypersensitivity to dopamine release, which results in an increase in cue sensitivity (24).

Other studies also suggest that approximately half of cocaine-dependent persons who do not have schizophrenia display craving in response to cocaine cues (11,15). Our data confirm this finding for this group and extend such research by demonstrating that almost all of the cocaine-dependent persons with schizophrenia reacted to cocaine cues with increased craving. These data suggest that persons with cocaine dependence and schizophrenia may be particularly sensitive to drug cues and vulnerable to relapse after exposure to drug cues in the environment. Although results conflict as to whether craving is the primary precursor to relapse, there is sufficient evidence to view craving as a motivational state that plays a role in continued drug use and that should be treated (25). Furthermore, previous research suggests that individuals with cocaine dependence and schizophrenia have higher rates of dropout from outpatient treatment than others and more recurrent hospitalizations (26). These persons may require specialized psychosocial and pharmacological interventions to manage their intense craving state and to reduce relapses.

These preliminary findings have strong implications for the etiology and maintenance of substance use disorders among persons with schizophrenia. Individuals with schizophrenia may abuse cocaine and other drugs in an effort to tolerate their severe and debilitating psychological symptoms as well as the extrapyramidal side effects of their medications (27). An equally plausible suggestion is that cocaine-dependent individuals with schizophrenia experience more intense craving than others and continue to use cocaine despite undesirable consequences because of heightened dopamine abnormalities early in recovery from substance dependence, particularly during protracted withdrawal (28). Roy and associates (29) also found dopamine disturbances early in recovery among persons addicted to cocaine, which persisted for eight weeks and which were correlated with craving scores.

These preliminary results warrant cautious interpretation because of the lack of a structured interview to maximize certainty about substance abuse and psychiatric diagnoses and because of the absence of objective physiological measures of changes in craving after cue exposure. The use of objective physiological measures would overcome the problem of addicted persons' minimizing their use of cocaine. Although this study omitted neutral cues in order to minimize the complexity of the cue-exposure procedure, the inclusion of a control procedure would be an important next step in this line of research.

Despite these limitations, the preliminary results support the need to develop specialized treatments to manage craving, particularly among cocaine-dependent persons with schizophrenia. An emerging body of literature suggests that the atypical neuroleptic agents may be useful for treatment of cocaine addiction among persons with schizophrenia. For example, preliminary reports suggest that clozapine (30,31,32) and olanzapine (33) have been efficacious in reducing craving and preventing relapses to substance abuse among persons with cocaine dependence and schizophrenia. Our group recently completed a study that compared risperidone to typical neuroleptics in the treatment of cocaine-dependent individuals with schizophrenia (20). The results suggest that the participants treated with risperidone experienced significantly less craving, fewer relapses to substance abuse, and better treatment compliance than participants treated with conventional neuroleptics. Double-blind studies are needed to further clarify the efficacy of atypical antipsychotic medications in the treatment of cocaine addiction among individuals with schizophrenia.

Dr. Smelson and Dr. Losonczy are affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, VISN 3, in the Bronx, New York, and with the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Piscataway. Mr. Kilker, Dr. Starosta, Dr. Kind, and Dr. Williams are with the VA New Jersey Health Care System in Lyons. Dr. Ziedonis is affiliated with the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Send correspondence to Dr. Smelson, Department of Veterans Affairs, New Jersey Health Care System, Lyons Campus, Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences Building 143, 151 Knollcroft Road, Lyons, New Jersey 07939-5000 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and cocaine use history of cocaine-dependent study participants with and without schizophrenia

1. Fishman MW, Foltin RW: Self-administration of cocaine by humans: a laboratory perspective. CIBA Foundation Symposium 166:165-173, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

2. Withers NW, Pulvirenti L, Koob GF, et al: Cocaine abuse and dependence. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 15:63-78, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Journal of the American Medical Association 264:2511-2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Carol G, Smelson DA, Losonczy MF, et al: A preliminary investigation of cocaine craving among persons with and without schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 52:1029-1031, 2001Link, Google Scholar

5. Flowers Q, Elder IR, Voris J, et al: Daily cocaine craving in a 3-week inpatient treatment program. Journal of Clinical Psychology 49:292-297, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Robbins SJ, Ehrman RN, Childress AR, et al: Mood state and recent cocaine use are not associated with levels of cocaine cue reactivity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 59:33-42, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Childress AR, Ehrman RN, McLellan AT, et al: Conditioned craving and arousal in cocaine addiction: a preliminary report. NIDA Research Monograph 81:74-80, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

8. Margolin A, Avants K, Kosten TR: Cue-elicited cocaine craving and autogenic relaxation: association with treatment outcome. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 11:549-552, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Johnson BA, Chen YR, Schmitz J, et al: Cue reactivity in cocaine-dependent subjects: effects of cue type and of cue modality. Addictive Behaviors 23:7-15, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. O'Brien CP, Childress AR, McLellan T, et al: Integrating systematic cue exposure with standard treatment in recovering drug dependent patients. Addictive Behaviors 15:355-365, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Avants KS, Margolin A, Kosten T: Differences between responders and non-responders to cocaine cues in a laboratory. Addictive Behaviors 20:215-224, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Grant S, London ED, Newlin DB, et al: Activation of memory circuits during cue-elicited cocaine craving. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U S A 93:12040-12045, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Maas LC, Lukas SE, Kaufman MJ, et al: Functional magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:124-126, 1998Link, Google Scholar

14. Childress AR, Mozley PD, McElgin W, et al: Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. American Journal of Psychiatry 10:9-17, 1999Google Scholar

15. Smelson DA, Roy M, Roy A, et al: Electroretinogram in withdrawn cocaine-dependent subjects: relationship to cue-elicited craving. British Journal of Psychiatry 172:537-539, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Smelson DA, Roy M, Roy A, et al: Electroretinogram and cue-elicited craving in withdrawn cocaine-dependent patients: a replication. Journal of Drug and Alcohol Dependence 27:391-397, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Davis KL, Kahn RS, Ko G, et al: Dopamine in schizophrenia: a review and reconceptualization. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:1474-1486, 1991Link, Google Scholar

18. Seeman P, Bzowej NH, Guan HC, et al: Human brain D1 and D2 dopamine receptors in schizophrenia, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases. Neuropsychopharmacology 1:5-15, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Smelson DA, McGee-Caulfield E, Bergstein P, et al: Initial validation of the Voris Cocaine Craving Scale: a preliminary report. Journal of Clinical Psychology 55:135-139, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Smelson DA, Losonczy M, Davis C, et al: Risperidone decreases cue-elicited craving and relapses among individuals with schizophrenia and cocaine dependence. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 47:671-675, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Berger SP, Hall S, Mickalian JD, et al: Haloperidol antagonism of cue-elicited cocaine craving. Lancet 347:504-508, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Smelson DA, Roy A, Roy M: Risperidone diminished cue-elicited craving in withdrawn cocaine dependent patients. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:984, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Roy A, Roy M, Smelson DA: Risperidone, ERG, and cocaine craving. American Journal of Addictions 7:90, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Kosten TA, DeCaprio JL, Nestler EJ: Long-term haloperidol administration enhances and short-term administration attenuates the behavioral effects of cocaine in a place conditioning procedure. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 128:304-312, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Hufford C: Craving in hospitalized cocaine abusers as a predictor of outcome. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 21:289-301, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Ho AP, Tsuang JW, Liberman RP, et al: Achieving effective treatment of patients with chronic psychotic illness and comorbid substance dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1765-1770, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

27. Mueser KT, Bellack AS, Blanchard JJ: Comorbidity of schizophrenia and substance abuse: implications for treatment. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology 60:845-856, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Gawin FH, Kleber HD: Cocaine use in a treatment population: patterns and diagnostic distinctions. National Institute of Drug Abuse Research Monograph 61:182-192, 1985Google Scholar

29. Roy M, Roy A, Williams J, et al: Reduced blue cone electroretinogram in cocaine-withdrawn patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:153-156, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Buckley P: Novel antipyschotic medications and the treatment of comorbid substance abuse in schizophrenia. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 15:113-116, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Yovell Y, Opler LA: Clozapine reverses cocaine craving in a treatment-resistant mentally ill chemical abuser: case report and hypothesis. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases 182:591-592, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Albanese MJ, Khantzian EJ, Murphy SL, et al: Decreased substance use in chronically psychotic patients treated with clozapine. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:780-781, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

33. Smelson DA, Kaune M, Kind J, et al: The Efficacy of Olanzapine Versus Haloperidol in Decreasing Cue-Elicited Craving and Relapse in Withdrawn Cocaine Dependent Schizophrenics. Presented at the National Institute of Drug Abuse New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit Conference, Boca Raton, Fla, May 1-4, 1999Google Scholar