Economic Grand Rounds: An Early Case Study of the Effects of California's Mental Health Parity Legislation

In a December 2001 vote on a parity amendment proposed by Senators Dominici and Wellstone in the House of Representatives, Congressional efforts to remove discriminatory mental health coverage for millions of Americans were defeated. Opposition to the amendment centered on employers' electing to reduce the availability and extent of health coverage in the coming year in anticipation of increasing costs to insurance companies (1).

In contrast, state legislatures have been more persuaded by published studies, which have suggested that an expansion of mental health and substance abuse benefits will not significantly increase overall health care costs (2,3). California's parity legislation is similar to the Dominici-Wellstone amendment in that it prohibits insurers from setting limits on treatment and services that are more restrictive than those for general medical care and also prohibits insurers from requiring higher copayments than those for general medical care. However, details of the bill restrict parity benefits for adults to persons with severe mental disorders.

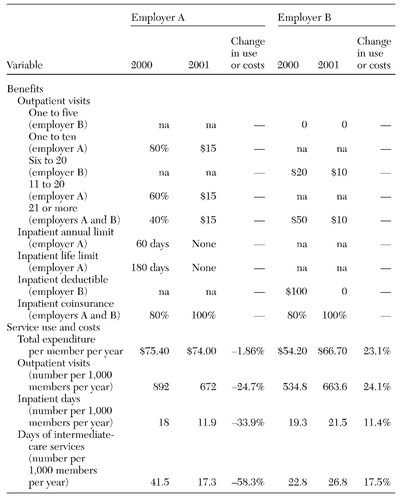

In this column we describe the experience of two large employer groups in California that implemented parity in mental health benefits on January 1, 2001, under plans provided through a managed behavioral health organization (MBHO). The changes the employers made to their benefits, changes in total mental health spending, and changes in the annualized use of inpatient, outpatient, and intermediate-care services per 1,000 members for mental health and substance abuse services are summarized in Table 1.

Percent change was calculated for the preparity period of January 1 to June 30, 2000, and for a comparable postparity period, January 1 to June 30, 2001. Both employer groups were made up of highly educated persons with correspondingly high levels of service use before and after the implementation of parity in mental health benefits. A substantial number of members of both employer groups were located in one metropolitan area.

Employer A (24,103 covered individuals) experienced a 1.9 percent decline in total spending and substantial reductions in the use of outpatient, intermediate-care, and inpatient services. Nevertheless, overall service use was high compared with that of other employer populations. Employer B (58,939 covered individuals) had lower levels of service use before parity than employer A and experienced a large increase in service use and spending. Nevertheless, even this large increase in behavioral health spending was well under 1 percent of total health care spending for employer B.

Why these differences between employers? Employer A's entire workforce had been under managed behavioral health care, so there was no adverse selection. However, employer B offered other plans with more expensive case mixes. When parity in mental health benefits was implemented, persons who had incurred higher costs before parity came into the preferred-provider-organization plans of the MBHO. In the first quarter of the post-parity period, 17 percent of the new users in the system were also new to the MBHO plans, and they incurred costs that were 48 percent higher than those of new users who were not new to the MBHO plan.

Thus about a third of the total change in costs was probably attributable to adverse selection. Under employer A's full carve-out arrangement—the MBHO manages all employees and dependents—9 percent of new users were also new to the MBHO plans, and these users incurred costs that were 16 percent lower than those incurred by other new users.

Despite the two employers' different responses to parity, these findings are reassuring even if they are not definitive. Even the $12 per-member-per-year increase of employer B represents a small percentage of total health care spending, particularly given that employer B's plan was 18 percent less expensive than employer A's plan before parity. Furthermore, an estimated one-third of employer B's increase represents a shift in dollars from one plan to another rather than a real increase in health care costs.

Although it is not possible to make generalizations from the experience of two employers, the findings illustrate an ideal legislative outcome—plans with high costs and high service use show stable or declining spending, and lower-cost plans show increases at a tolerable level (less than 1 percent). Whether convergence of service use and costs occurs more broadly in response to parity mandates awaits more comprehensive studies across a broad range of benefit plans and populations.

Dr. Branstrom is a senior research analyst in the health care industry. Dr. Sturm is senior health economist at Rand Corporation in Santa Monica. Send correspondence to Dr. Branstrom at 4346 Edgewood Avenue, Oakland, California 94602 (e-mail, [email protected]). Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Changes in benefits, service use, and costs for two California employers before (2000) and after (2001) the implementation of parity in mental health benefits

1. Pear R: Drive for more mental health coverage fails in Congress. New York Times, Dec 19, 2001Google Scholar

2. Sturm R, Goldman W, McCulloch J: Mental health and substance abuse parity: a case study of Ohio's state employees' program. Journal of Mental Health and Economics 1:129-134, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Sturm R: How expensive is unlimited mental health care coverage under managed care? JAMA 278:1533-1537, 1997Google Scholar