Seven-Year Outcomes of Patients Evaluated for Suicidality

Abstract

This study assessed the seven-year outcomes of 137 patients who presented with suicidality. Forty-five of the patients were contingently suicidal, that is, they originally presented with suicidal threats designed to gain hospital admission; 92 patients were noncontingently suicidal. Administrative and clinical records were examined for adverse outcomes, and suspicious cases were further investigated. Significant differences were found between the groups in overall mortality and serious suicide attempts. Although no suicides were identified in the contingently suicidal group, ten suicides were confirmed or highly suspected among the noncontingently suicidal patients. This group also had higher overall death rates. These results argue for evaluation of contingency in suicide risk assessments.

Suicide risk management is one of the most important tasks mental health professionals perform. The emergency evaluation of potentially suicidal patients must take into account immediate risk factors for suicide, such as a recent attempt, hopelessness, intoxication, psychosis, or unwillingness or inability to reassure the clinician that no imminent self-harm will occur. Long-term risk factors for suicide, such as past attempts, serious mental illness, alcohol dependence, advanced age, male gender, Caucasian race, and poor health, also must be considered but are less amenable to acute interventions (1,2).

In some settings, patients with social difficulties such as homelessness or legal problems present themselves as suicidal in order to be admitted to the hospital (3). Acute suicidality tops most checklists of admission criteria and is the justification for many admissions (4), although the effect of brief hospitalizations on long-term suicide risk is unknown. Admission in these situations offers shelter, solace, and an escape from legal or social difficulties, but it is costly and seldom provides long-term solutions for the underlying problems. Crisis intervention, addiction rehabilitation, social services, and legal support are less costly options that may focus intervention on factors that contribute to suicide risk. However, use of these approaches may not allay clinicians' anxiety about their patients' potential for suicide (5,6). Despite the high stakes—both in terms of possible suicide and in terms of use of resources—few research data are available to inform clinical decision making in the assessment of acutely suicidal patients.

The purpose of this paper is to present seven-year follow-up data on completed suicide, serious suicide attempts, and overall mortality for a cohort of 137 patients who presented as acutely suicidal during a one-year period.

Methods

Study subjects were originally identified retrospectively after being evaluated for acute suicide risk in the psychiatric triage area of a Department of Veterans Affairs tertiary care medical center (4). A total of 137 patients with acute suicidal presentations were identified from 1,381 psychiatric triage assessments conducted between September 1, 1993, and August 31, 1994.

These 137 identified cases were screened for contingent suicidality. The operational definition of contingent suicidality was that either the patient made suicide threats or statements that were linked to the admission decision—for example, "I will kill myself if you do not admit me"—or the medical record documented the patient's having acknowledged, after admission, that he or she had exaggerated suicidality during the screening process in order to be admitted. Forty-five patients were identified as contingently suicidal, and the remaining 92 patients were categorized as noncontingently suicidal.

A review conducted six months after the initial evaluation revealed no statistically significant differences in mortality, serious suicide attempts, or completed suicide between the two groups. Clinicians who subsequently provided care for the patients were unaware that they had been identified for prospective outcome evaluation.

The cases were reviewed again approximately seven years after the initial suicide assessment, in November 2000. If the medical center is aware of a patient's death, this information is entered in the patient's administrative record. The medical and administrative records of the patients in the study were examined for evidence of any serious suicide attempt, suspected or confirmed suicide, or death from any cause. All available progress notes and hospital discharge summaries were reviewed.

For the purposes of the follow-up review, a serious suicide attempt was defined as a self-inflicted injury or overdose serious enough to require hospitalization. Deaths were classified as highly suspected suicides if the last clinical entry shortly before a suspicious death indicated a concern about suicide. For example, one patient had a documented preoccupation with riding his bicycle into traffic. Soon after revealing this fantasy, he was killed in a bicycle-automobile accident, which the county medical examiner ruled as accidental. Each suspected suicide was referred to our medical center risk manager, who checked the case with the county medical examiner's records.

Results

Significant diagnostic and demographic differences were noted between the contingently and noncontingently suicidal groups. Statistical analysis was conducted with GraphPad InStat software (7). At the time of initial assessment the mean±SD age of the contingently suicidal group was 42.3±26.1 years, compared with 45.2±27.8 years for the noncontingently suicidal group. The mean age for all 137 study subjects was 44.4±27 years. Most patients were men (N=130, or 94.9 percent).

Patients in the contingently suicidal group were more likely to have diagnoses of substance dependence and antisocial personality disorder, to be unmarried, to be homeless, and to have legal difficulties. Patients in the noncontingently suicidal group were more likley to have a diagnosis of major depression.

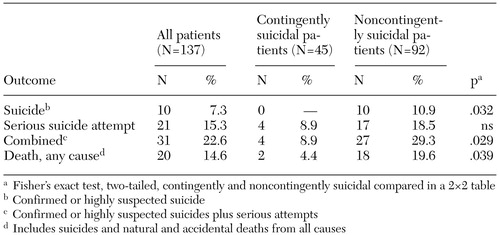

Table 1 summarizes the findings of the follow-up evaluation. Overall, seven confirmed suicides and three highly suspected suicides were identified. All ten occurred in the noncontingently suicidal group. Among the 137 patients in the study, 20 died from any cause, including suicide, during the seven-year period. Of these, 18 were in the noncontingent group, whereas only two patients in the contingent group died, and their deaths were from causes other than suicide.

Four of the patients in the contingent group made at least one serious suicide attempt during the follow-up period, compared with 17 patients in the noncontingent group. The total number of serious suicide attempts—including completed suicides, highly suspected suicides, and serious suicide attempts not completed—was significantly higher among patients in the noncontingent group than among those in the contingent group (27 versus four, p=.029).

Discussion

The overall mortality of 14.6 percent after seven years for this middle-aged cohort is a strong reminder of the health risks and problems that often accompany mental illness that is serious enough to be associated with suicidality. This finding is consistent with other investigators' reports of mortality from all causes in psychiatric populations (8,9). The finding of ten probable completed suicides, in many cases despite extensive clinical interventions with patients known to be at risk, highlights both the importance and the difficulty of managing suicide risk over the long term. The costs and morbidity associated with 31 suicide attempts serious enough to be fatal or to warrant hospitalization are also noteworthy.

The findings reported here should be considered tentative, given the methodological limitations of the study. The sample is too small for definitive conclusions to be drawn. The study subjects were mainly middle-aged male veterans, which limits the generalizability of the results. Unique characteristics of suicidal veterans have been described in the literature (2,10).

Another limitation is that the study subjects were originally identified retrospectively and then monitored prospectively. Moreover, the method of identifying suicide was relatively limited, and definitively tracing all relocated patients was beyond the resources available for the study. It is also possible that the clinical and social characteristics of the contingently suicidal group made identifying the outcomes assessed more difficult. These factors could have led to undercounting suicides and serious suicide attempts.

The differences in the numbers of serious suicide attempts and completed suicides between the two groups appear to support the hypothesis that the original designation of contingently versus noncontingently suicidal has some predictive value. Contingency in this context is probably a continuous variable rather than an all-or-nothing condition, so a rating system might be useful as an adjunct to clinical assessment. If the concept of contingency could be further operationalized, measured, and validated, it could be helpful to clinicians and managers who make admission decisions in acute settings in which secondary gain issues must be sorted out during suicide risk assessments. This would allow resources for acute inpatient care to be channeled to the less contingently suicidal patients and more appropriate services directed to the needs of those who are contingently suicidal.

Conclusions

The results of this study reinforce the reality of suicide risk among patients with mental illness. The difference in outcome over a seven-year period between contingently and noncontingently suicidal groups argues for further investigation of the concept of contingency in suicide assessment in the hopes of more accurately identifying patients who are at risk of completing suicide.

Dr. Lambert is associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School at Dallas, 116A, 4500 South Lancaster Avenue, Dallas, Texas 75216 (e-mail, [email protected]). He is also medical director of the mental health service of the Veterans Affairs North Texas Health Care System in Dallas.

|

Table 1. Outcome seven years after initial psychiatric triage evaluation of 137 suicidal patients

1. Lambert MT: Psychiatric crisis intervention in the general emergency service of a Veterans Affairs hospital. Psychiatric Services 46:283-284, 1995Link, Google Scholar

2. Lambert MT, Fowler DR: Suicide risk factors among veterans: risk management in the changing culture of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:350-358, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Pinsker H: The allegedly suicidal patient in the general hospital. General Hospital Psychiatry 3:277-282, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Sederer LI, Summergrad PS: Criteria for hospital admission. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:116-118, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Lambert MT, Bonner J: Characteristics and six-month outcome of patients who use suicide threats to seek hospital admission. Psychiatric Services 47:871-873, 1996Link, Google Scholar

6. Buzan RD, Weisberg MP: Suicide: risk factors and therapeutic considerations in the emergency department. Journal of Emergency Medicine 10:335-343, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. GraphPad InStat Statistical Software, version 2.05a. San Diego, GraphPad Software, 1990Google Scholar

8. Black DW, Warrack G, Winokur G: The Iowa record-linkage study: I. suicides and accidental deaths among psychiatric patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:71-75, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Koran LM, Sox HC, Marton KI: Medical evaluation of psychiatric patients: I. results in a state mental health system. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:733-740, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lehmann L, McCormick RA, McCracken L: Suicidal behavior among patients in the VA health care system. Psychiatric Services 46:1069-1071, 1995Link, Google Scholar