Datapoints: Trends in Psychiatric Practice, 1988-1998: III. Activities and Work Settings

Major changes have occurred in the financing and organization of the mental health care system. These changes are particularly evident when trends in psychiatrists' professional activities and the settings of these activities are examined. This is the third and final column in a series focusing on changes in the practice of psychiatry as revealed in analyses of data from two large national surveys of psychiatrists, the 1988-1989 Professional Activities Survey (1) and the 1998 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice (2).

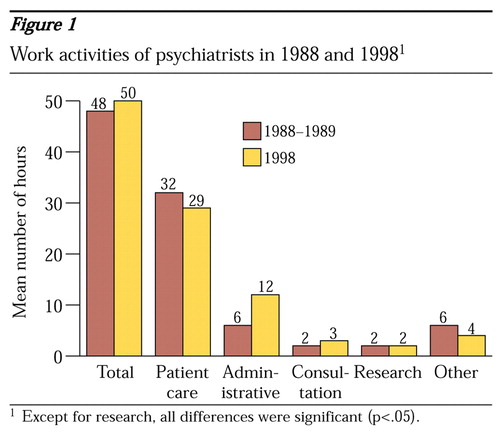

The number of hours in a typical psychiatrist's work week has increased from 48 in 1988 to 50 in 1998 (t=4.2, df=947, p<.001). Psychiatrists are spending significantly more time on administrative tasks (Figure 1) (t=16.4, df=928, p<.001). Although the largest part of the typical work week in both 1988 and 1998 was spent in direct patient care, the actual number of hours has decreased significantly—from 32 to 29 hours of direct care (t=6.4, df= 959, p<.001).

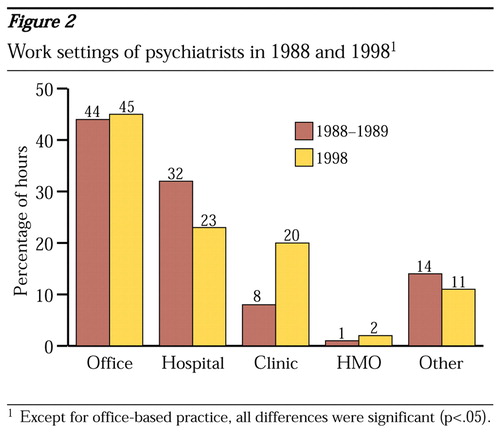

In both 1988 and 1998 the most common setting was office-based practice (Figure 2). However, in 1998 psychiatrists spent a significantly higher proportion of their time in clinics (20 percent versus 8 percent in 1988; t=9.8, df=874, p<.001) and a significantly smaller proportion in hospital settings (23 percent versus 32 percent in 1988; t=7.8, df=927, p<.001).

These data confirm previous findings and help quantify the impact of our changing health care environment on psychiatric practice (3,4). Even though psychiatrists now spend more hours at work, a larger proportion of that time is diverted from direct patient care. In addition, providing care in hospitals is becoming a less prominent part of psychiatrists' work week, and their time in outpatient clinics is increasing. More research is needed to understand the effects of these changes on patient care.

Ms. Suarez and Ms. Tanielian are affiliated with Rand, 1200 South Hayes Street, Arlington, Virginia 22202 (e-mail, ana_ [email protected]). Dr. Marcus is with the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work in Philadelphia. Dr. Pincus, who is editor of this column with Ms. Tanielian, is affiliated with Rand in Pittsburgh and with the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Figure 1. Work activities of psychiatrists in 1988 and 19981

1 Except for research, all differences were significant (p<05).

Figure 2. Work settings of psychiatrists in 1988 and 19981

1 Except for office-based practice, all differences were significant (p<05).

1. Dorwart RA, Chartock LR, Dial T, et al: A national study of psychiatrists' professional activities. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1499-1505, 1992Link, Google Scholar

2. National Survey of Psychiatric Practice. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, Office of Research, 1998Google Scholar

3. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Pincus HA: Trends in office-based psychiatric practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:451-457, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Kletke PR, Emmons DW, Gillis KD: Current trends in physicians' practice arrangements, from owners to employees. JAMA 726:555-560, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar