Rehab Rounds: Social Skills Training to Help Mentally Ill Persons Find and Keep a Job

Introduction by the column editors: Social skills training as a mode of treatment and rehabilitation of persons who have mental disabilities has been well documented for its efficacy in controlled clinical trials in the United States and in other countries (1). However, only a few attempts have been made to apply social skills training in the context of vocational rehabilitation (2,3,4). In a recent column, Wallace and colleagues (5) focused on one such effort—a module on workplace fundamentals—and presented data in support of the module's utility in facilitating the job adjustment of persons who have serious mental illness (5).

In this month's column, Tsang describes a similar program in Hong Kong that is based on the principles of social skills training and that focuses on job search and job tenure for persons with schizophrenia who have a high level of functioning. This program, derived from the "job club" approach of Jacobs and colleagues (3), could be said to have been inspired by the Social and Independent Living Skills Program (6) developed as a supplement to the "place and train" model of supported employment (7).

I taught a module entitled Social Skills for Finding and Keeping a Job for more than five years in mental hospitals and day hospitals in Hong Kong with considerable success among persons who had persistent psychoses. Clients were recruited for the module by asking clinicians to refer all unemployed individuals between the ages of 18 and 50 years who had serious and persistent mental illness, who had at least a fifth-grade education, and who did not have a concurrent diagnosis of mental retardation. Most of the clients had schizophrenia, although a small proportion had affective or personality disorders.

Referred patients underwent an initial screening to determine whether they were suitable for participation in the program. During an intake interview, potential participants were asked whether they would be willing to participate in a program that would prepare them to obtain and keep a competitive job. Individuals who were willing to make the commitment to participate in the module were enrolled if they were capable of understanding the nature of the program, had few negative symptoms, had previous work experience, and had supportive families.

About 20 percent of referred clients participated in the program. The main reason for not including a referred client was the client's refusal to participate after he or she had heard all the requirements of the training program.

Format of the module

The module is presented in a three-tier hierarchical structure; participants master the concepts and skills in each tier before proceeding to the next tier. The first tier of the module covers basic social skills—with a focus on interpersonal communication—and basic job survival skills. Communication skills involve receiving, processing, and sending information, as defined by Liberman and colleagues (8,9). Basic job survival skills include grooming, politeness, and personal appearance.

The second tier contains two groups of core skills that are needed to handle both general and specific work-related situations. General skills are required for coping with any job, irrespective of the specific characteristics of the job. General work-related skills can be divided into those that are essential for securing a job, such as making a good impression in an initial job interview, and those needed to retain a job, such as maintaining a good working relationship with a supervisor. The latter set of skills may be further subdivided to account for the three groups of people with whom an employee must interact: supervisors, colleagues, and subordinates. The second group of core skills are those for coping with situations that are specific to a particular kind of job. For example, a receptionist must have the necessary skills for dealing with inquiries from a company's visitors or customers, and a salesperson in a clothing store must know how to sell the store's products and how to cater to the needs of the store's customers.

The third tier of the module focuses on the goals for which the basic and core skills prepare participants—that is, the benefits a person can gain as a result of having those skills. These benefits are the consequences of getting a job, such as salary, social contacts, structure for one's time, and a sense of achievement and satisfaction from working. The skills taught in this program have been validated through a survey that was conducted among people with schizophrenia as well as psychiatric rehabilitation counselors and members of the workforce who were not suffering from a mental illness (10).

The module consists of ten weekly sessions, each lasting one and a half to two hours. This time commitment fits into the clinical workloads of most psychiatric rehabilitation professionals. The module can be delivered to individual clients or to a group. Although the participants ideally would have first received training in basic social skills (9), this ideal is not always possible. Consequently, to facilitate learning of more advanced social skills, session 1 provides a review of basic social skills and an introduction to the module. The aims of this first session are to explain the purpose, format, and requirements of the module and to provide an opportunity to practice basic verbal and nonverbal social skills, such as gestures, facial expressions, and conversation techniques.

Session 2 covers basic survival skills, such as medication and symptom management, which are prerequisites for acquiring the more advanced skills needed to find and keep a job. Sessions 3 and 4 focus on job-acquisition skills, such as those required to approach potential employers and to prepare for a job interview. Session 4 teaches the skills required to participate in a job interview. This session includes common questions asked by interviewers and provides opportunities to rehearse a variety of answers to these questions.

Sessions 5 through 8 center on the social skills that are needed to maintain a job. Job-retaining skills are divided into interactions with supervisors, such as requesting urgent leave without damaging the relationship, and interactions with coworkers, such as asking for instructions on work procedures. In session 5, assertiveness is introduced as a basic technique that is often useful in interacting with supervisors. For example, participants practice declining a request to work overtime on the grounds that they feel very tired. Participants are also taught how to request leave, such as vacation or sick leave, from their supervisor.

In session 6, the participants continue to practice turning down unreasonable requests from supervisors. In session 7, cooperation skills are introduced as a basic means of interacting with coworkers. Session 8 teaches the necessary social skills for resolving minor conflicts with coworkers. Meanwhile, basic problem-solving techniques are introduced to help participants choose the most appropriate solution to a problem from several alternatives.

Session 9 focuses on the social skills necessary for handling specific work-related situations. In this session, several popular jobs among people who have schizophrenia—for example, sales clerk and janitor—are used to illustrate various social skills required for success in keeping a job. In session 10, more examples are provided to help consolidate the problem-solving and social skills that have already been introduced.

The format of the individual training sessions follows the structure typically used in social skills training (9). Each session includes warm-up activities, instruction, demonstration, role-playing, feedback, and homework. The warm-up activities are designed to allow the participants to practice some aspects of social behaviors in an exaggerated way. For example, when rehearsing the basic nonverbal skills, the participants play a game that requires them to use only gestures and facial expressions to communicate their likes and dislikes to each other.

This strategy is intended to make participants aware of the importance of nonverbal behaviors in interpersonal communication. Instruction consists of short lectures presented by the trainer, who uses a flip chart and handouts to overcome the difficulties that individuals with serious mental illness often have in learning new material. Ample time is provided so that the participants can ask questions and discuss areas of concern.

During the demonstrations, the trainer models appropriate behaviors for specific social situations. For example, in session 5 the trainer demonstrates how to make a request of a supervisor. Participants learn through observing the social behaviors of the trainers and consolidate their learning by playing similar roles. After the role-playing exercise, the participants get feedback from the trainer and from other participants. Finally, participants practice their skills outside the training environment by completing homework and guided practice. Because the participants do not have jobs at this stage, they obtain this guided practice mainly in the training workshop of the day hospitals.

Although the program can be implemented in different therapeutic settings, most of my experience with it has been in day hospitals. The day hospital staff includes psychiatrists, nurses, and occupational therapists, who can offer warm and noncritical encouragement to participants and can help them implement the new skills, overcome obstacles, and use medications and coping techniques for dealing with stress and other symptoms.

Assessing progress

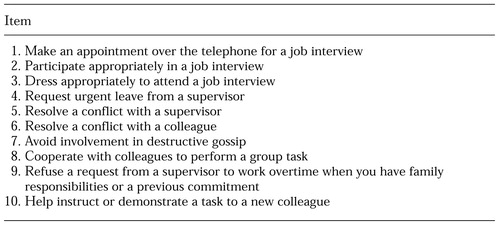

To assess participants' progress in the training module, a validated two-part measure consisting of a self-administered checklist and a role-playing exercise is used before and after the program (10). The ten-item self-administered checklist measures each client's self-perceived competence in handling work-related social situations during the previous three months on a scale of 1 to 6 (Table 1). Each item focuses on a particular skill that is needed to acquire and maintain a job.

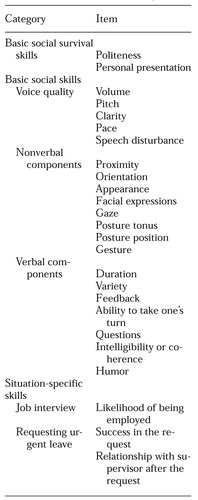

The aim of the role-playing exercise is to assess two specific types of social skills that are required to find and keep a job. The exercise consists of two simulated situations: participating in a job interview, and requesting urgent leave from a supervisor. The participant performs the role-playing exercise with another participant, who plays the role of the interviewer in the first scene and the supervisor in the second. The participant is rated on basic social survival skills such as grooming and politeness, basic social skills such as voice tone and volume, eye contact and posture, and situation-specific skills (Table 2). The rater uses a scale of 0 to 4, where 0 represents poor performance—either excesses or deficiencies in the target behavior—and 4 represents normal performance, to rate a total of 25 items. Monitoring the development of skills in this way allows trainers to reinforce areas of progress and target areas that need further work.

Case vignette

Mr. J, a 42-year-old single man with schizophrenia, was unemployed for almost two years and lived at a supported housing facility. Although he was motivated to work, he lacked the confidence and skills to do so. In the pretraining assessment exercise, Mr. J obtained a score of only 32 out of 60 on the ten-item self-administered checklist. In particular, Mr. J rated "participate appropriately in a job interview" and "resolve a conflict with a supervisor" as "often difficult." In the role-playing exercise, his score was 75 out of 100. His main area of weakness was in using nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions and gestures, to communicate. Also, Mr. J had low scores for situation-specific skills, such as asking his supervisor for leave.

After almost three months of training within the ten-session format, Mr. J's confidence and job skills improved. For example, in the posttraining assessment, he obtained a score of 37 on the self-administered checklist and a score of 90 in the role-playing exercise. Mr. J improved his voice quality and nonverbal social skills as well as his situation-specific skills, such as making requests. He was then encouraged to seek competitive employment.

During the first month after training, Mr. J was unable to obtain a position. He was invited for a follow-up group session during which the trainer provided encouragement and reinforcement and reviewed problem-solving techniques. Also, the trainer prompted participants to share their experiences over the previous month. Mr. J was impressed by the success stories he heard from other members of his group.

After the session, Mr. J and the trainer discussed some of the problems Mr. J was having in his search for a job. Mr. J believed that the most difficult barrier he had to overcome was his awkwardness during job interviews. The trainer helped Mr. J to work on his job interview skills and his nonverbal skills—such as voice volume and eye contact—to enhance his confidence during interviews. Three weeks later, Mr. J obtained a job as a watchman in a private residential building. He continued to attend the monthly follow-up group meetings. Three months later, Mr. J was still working and reported that he was satisfied with his job. He had good relationships with his supervisor and peers, and he had received positive comments on his performance.

Evaluation of the module

A controlled study was conducted to validate the efficacy of the module on finding and keeping a job (11). Ninety-seven participants who had schizophrenia were randomly assigned to one of three groups: training with follow-up support (N=30), training without follow-up support (N=26), or a control group that received assessment only (N=41). The two groups that received training showed significant improvements in job-related social skills after the training module. Three months after the participants completed the training module, their employment status and workplace adjustment were assessed with a questionnaire created for this study.

Participants in the group that received follow-up support were more successful in obtaining employment than those in the group that did not receive follow-up support. Fourteen (47 percent) of the participants who received training plus follow-up support were employed at the time of the three-month follow-up assessment. Only six (23 percent) of the participants who received training but no follow-up support were employed at the time of the assessment. In the control group, only one participant was employed at the three-month follow-up. Moreover, the participants in the group that received follow-up support reported that they were generally satisfied with their jobs and able to develop harmonious relationships with their supervisors and colleagues.

Several reasons can be cited for the high success rate of the module on finding and keeping a job. First, many of the eligible clients were functioning at a very high level and were motivated to join the group. The group was different from other available groups in the community, because it was geared toward a fundamental goal of many individuals who have serious mental illness: to obtain employment in the competitive job market.

Second, the positive results were probably due to the support available to the clients for three months after they had completed the module. As illustrated in the case vignette, the level of support that is given to participants can make or break their efforts to maintain competitive employment. In fact, we are concerned that the sustained employment of the participants may erode after three months because of a lack of resources to provide further follow-up.

Afterword by the column editors: The employment rate reported by Tsang after these patients participated in his ten-session module is similar to that reported by Drake and colleagues (7,12) in their use of individual placement and support, a form of supported employment previously described in this column. This similarity in results suggests that the supportive and continuing contacts that are inherent in the program, along with skills training, may be critical elements in improving the employability of persons who have schizophrenia. Further evidence can be found in the work of Jacobs and his colleagues (3), who developed a skills training program that provided time-limited follow-along support. The results of their "job club" were excellent for nonpsychotic participants—for whom employability was about 60 percent—but were meager for persons who had schizophrenia (12 percent employability) or bipolar disorder (23 percent employability). These outcomes are similar to those observed in the group that did not receive ongoing support in Tsang's study.

It appears that time-unlimited continuing support, encouragement, and problem solving skills are critical to the successful competitive employment of persons who have serious and persistent mental illness. Just as long-term antipsychotic medication is vital for sustaining improvements in symptoms or remission of psychotic disorders, long-term psychosocial supports that reinforce the use of job skills in everyday employment are key elements in the achievement of positive outcomes in the vocational realm.

Persons who have schizophrenia or other mental disabilities may benefit from a combination of supported employment and training in the skills that are required for job tenure. Given that even the best supported employment programs, such as individual placement and support, still achieve only 50 percent employability and that about half of these individuals are not employed at six- to 18-month follow-up, much improvement is needed in the employment outcomes of persons who have schizophrenia and associated disorders. Wallace, Marder, Drake, Becker, Nuechterlein, Glynn, and Liberman are currently conducting two randomized controlled trials at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and at Dartmouth on the benefits of individual placement and support alone or combined with a module on workplace fundamentals for persons who have schizophrenia—employability, sustained employment, social adjustment, and quality of life.

The benefits derived from the workplace fundamentals module, combined with the preliminary results reported in this column, suggest that social skills training can be useful in facilitating job search and job tenure for persons who have schizophrenia or other severe mental illnesses. Additional research is needed to determine how social skills training should be integrated into vocational rehabilitation programs such as individual placement and support and supported employment to enhance clients' likelihood of becoming gainfully employed in the community and keeping their jobs. For example, is a hierarchical structure in which basic skills are taught before work-related skills the most effective method of teaching social competence? Obviously the answer to this question has significant implications for strategies to return individuals who have schizophrenia to the workforce.

Although social skills training has been shown to be effective in helping people who have schizophrenia to adjust to the demands of employment, many of these individuals do not benefit from this form of treatment. One method for improving the portability of job skills training is to package the intervention in a way that parallels the format of the modules developed at UCLA (6). With appropriate in-service training, any member of the clinical staff—psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, or occupational and recreational therapists—should be able to conduct Tsang's module on finding and keeping a job.

Dr. Tsang is assistant professor in the department of rehabilitation sciences at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hunghom, Hong Kong (e-mail, [email protected]). Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., and Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Self-administered checklist for participants in a program to help mentally ill persons find and keep a job

|

Table 2. Role-playing exercise for participants in a program to help persons who have mental illness find and keep a job

1. Liberman RP: International perspectives on skills training for the mentally disabled. International Review of Psychiatry 10:5-8, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Kelly JA, Laughlin C, Claiborne M, et al: A group procedure for teaching job interviewing skills to formerly hospitalized psychiatric patients. Behavior Therapy 10:299-310, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Jacobs HE, Kardushian S, Kreinbring RH, et al: A skills-oriented model for facilitating employment among psychiatrically disabled persons. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 28:87-96, 1984Google Scholar

4. Mueser KT, Foy DW, Carter MJ: Social skills training for job maintenance in a psychiatric patient. Journal of Counseling Psychology 33:360-362, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Wallace CJ, Tauber R, Wilde J: Teaching fundamental workplace skills to persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:1147-1153, 1999Link, Google Scholar

6. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: the UCLA social and independent living skills modules. Innovations and Research 2:43-60, 1993Google Scholar

7. Drake RE, Becker DR: The individual placement and support model of supported employment. Psychiatric Services 47:473-475, 1996Link, Google Scholar

8. Liberman RP, Mueser KT, Wallace CJ, et al: Training skills in the psychiatrically disabled: learning coping and competence. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:631-647, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Liberman RP, DeRisi WJ, Mueser KT: Social Skills Training for Psychiatric Patients. Needham, Mass, Allyn & Bacon, 1989Google Scholar

10. Tsang HWH, Pearson V: Reliability and validity of a simple measure for assessing the social skills of people with schizophrenia necessary for seeking and securing a job. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 67:250-259, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Tsang HWH, Pearson V: A work-related social skills training program for people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:139-148, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Bebout R, et al: A randomized clinical trial of supported employment for inner-city patients with severe mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:627-633, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar