Primary Care Physicians' Experience With Mental Health Consultation

Abstract

A total of 684 primary care physicians in Wisconsin participated in a survey designed to explore their experiences of consulting with and referring patients to mental health care professionals. The respondents indicated that they had only moderate access to mental health care professionals, and even less access when a patient was covered by Medicare or Medicaid or had no insurance. Physicians in group practices that included at least one mental health professional reported having better access to care than those in practices that did not include mental health services. Perceived access to mental health care services was not related to community size or to a managed care setting.

When individuals develop symptoms of a psychiatric disorder, the first professional they contact is often their primary care physician. In fact, primary care physicians treat a wide range of psychiatric disorders, especially depression (1,2,3,4,5) and anxiety disorders (6,7). Health care delivery today is characterized by an emphasis on collaborative management, in which psychiatrists and other mental health professionals have consultative relationships with primary care physicians but the primary care physicians maintain the central role in managing the patient's psychiatric disorder (8).

Many effective models of consultation are described in the literature. Kates and colleagues (9) found high levels of satisfaction among family physicians and psychiatrists in Canada who participated in a "shared care model of consultation-liaison psychiatry," in which psychiatrists regularly visited family practices to see and discuss patients and to provide education and advice to the primary care provider. Another study found that telephone backup provided by a psychiatrist was an effective method of supporting family physicians (10).

This study examined the experiences and attitudes of primary care physicians in Wisconsin in their consultations with mental health professionals. The study was initiated because of concerns about whether primary care physicians had adequate access to psychiatric consultation, especially in rural areas of the state.

Methods

A questionnaire was sent in April 1997 to 418 randomly selected members of the 2,000-member Wisconsin Academy of Family Practice, to the 357 members of the Wisconsin Society of Internal Medicine who were not listed in their directory as subspecialists, and to all 651 members of the Wisconsin Chapter of the American Association of Pediatricians. The goal was to obtain responses from a representative sample of 200 physicians from each discipline.

The questionnaire contained seven questions designed to address four key issues in the relationship between primary care physicians and mental health professionals: the physician's access to mental health services, the type of consultation desired, the degree of responsibility for referred patients, and the quality of communication with mental health professionals. Additional information was solicited on whether the physicians considered themselves to be primary care professionals, their specialty, their type of practice, and the size of the community in which they practice.

The response rate for all three disciplines was about 62 percent. Data were analyzed for a total of 684 physicians who identified themselves as primary care physicians: 245 family physicians, 163 internists, and 276 pediatricians. One-way analyses of variance, stratified by practice type, were conducted for each questionnaire item.

Results

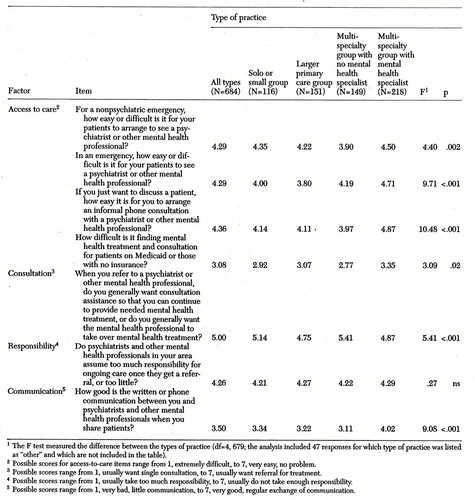

Table 1 presents the mean scores for the seven questionnaire items by the respondents' practice type. Overall, respondents indicated that they had only moderate access to mental health services for both routine, or nonemergency, and emergency mental health care and moderate access to informal consultation with mental health care professionals. The mean score for access to care for Medicaid and uninsured patients was below the scale midpoint.

Most of the respondents preferred to refer a patient to a mental health professional than to receive consultation assistance only; however, the physicians viewed mental health professionals as tending to take too little responsibility when they did receive a referral. Finally, respondents viewed the adequacy of communications with mental health professionals as less than ideal.

T tests (results not shown) were conducted on each of the seven questionnaire items to compare responses of primary care physicians who had at least one psychiatrist in their practice with those of physicians who did not. The analyses were significant for all four access-to-care items, with higher means for respondents who had a psychiatrist in the practice. These respondents also indicated significantly better communication with mental health practitioners. No significant differences for the items on preference for consultation versus referral or responsibility for the patient were found for physicians in different types of practice.

Reports of the relationship between generalist clinicians and mental health providers did not vary significantly by specialty, except for their preference for consultation or referral. Family physicians were evenly divided in their preference for a single consultation and a referral for treatment (mean scores of 4.48 and 5.05, respectively), and pediatricians leaned more heavily toward referral (mean score of 5.43). The difference between family practitioners and pediatricians was significant (p<.001).

A total of 405 respondents (61 percent) indicated that they practice in communities of 50,000 or more people; 139 (21 percent) practice in communities of 10,000 to 50,000, and 120 (18 percent) in communities of 10,000 or less. Community size was not significantly associated with any of the survey items, nor was participation in a managed care organization.

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, primary care physicians indicated that they had only moderate access to mental health care for most of their patients. As might be expected, physicians in a multidisciplinary group that included a psychiatrist or other mental health professional reported better—but still not optimal—access to mental health services. Also, primary care physicians across specialty groups and practice types reported difficulties in getting mental health consultation and care for patients who were enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid or who had no insurance.

An unexpected finding was that reported access to mental health care was not related to community size. This survey was undertaken mainly because of the investigators' concerns about access to mental health care in rural areas. Rural access may be less of a problem than previously thought, at least in Wisconsin, which has a relatively robust mental health system.

Also of some surprise was the finding that moderate access to mental health care was independent of whether the patient was seen within a managed care environment. Some health care professionals have hoped that managed care would facilitate access to mental health consultation when primary care physicians identified the need.

Although some differences by specialty and practice setting were observed, most primary care physicians preferred to refer patients to mental health providers for treatment, as opposed to just wanting consultation. This preference is somewhat at odds with the fact that the treatment of most people with potentially treatable anxiety disorders and depression is managed by their primary care physician. This finding should be explored by anyone who is developing policies that promote the use of mental health consultation rather than referral. An additional finding was that primary care physicians felt that mental health practitioners do not take enough responsibility for a patient's ongoing care after a referral has been made.

The factors that influence primary care physicians' preference for either providing mental health treatment themselves or referring a patient to a mental health professional need to be better understood. Do physicians who favor referrals lack the extra time that is often required to treat people with mental illness? Do they feel unqualified to treat mental illness? To what extent is reimbursement a factor in referrals?

Finally, the finding that access to mental health care is only moderate for patients who have insurance and is notably worse for those who are uninsured or who are covered by Medicare or Medicaid is a public policy issue that needs to be addressed. Primary care physicians endeavor to do their best to help patients with their psychosocial needs. Without adequate support from the mental health profession, this task is all the more difficult.

Dr. Kushner and Dr. Beasley are professors and Mr. Mundt is a programmer analyst in the department of family medicine at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where Dr. Diamond is a professor and Dr. Robbins is clinical associate professor in the department of psychiatry. Dr. Beasley is also director of the Wisconsin Research Network at the university, where Dr. Plane is an associate scientist. Dr. Robbins is also clinical associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Address correspondence to Dr. Kushner, University of Wisconsin, Department of Family Medicine, 777 South Mills Street, Madison, Wisconsin 53717 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Responeses (mean scores) of primary care physicians to a survey about their consulting experiences with mental health professionals, by type of practice

1. Katon W, Schulberg H: Epidemiology of depression in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry 14:237-247, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Schulberg H, Pajer K: Treatment of depression in primary care, in Mental Disorders in Primary Care. Edited by Miranda J, Hohmann AA, Attkisson CC, et al. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1994Google Scholar

3. Schulberg H, Block M, Madonia MJ, et al: Treating major depression in primary care practice: eight-month clinical outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:913-919, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Schulberg HC, Madonia MJ, Block MR, et al: Major depression in primary care practice: clinical characteristics and treatment implications. Psychosomatics 36:129-137, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Simon GE, VonKorff M: Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Archives of Family Medicine 4:99-105, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. DeGruy F: Treatment of anxiety in primary care, in Mental Disorders in Primary Care. Edited by Miranda J, Hohman AA, Attkisson CC, et al. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1994Google Scholar

7. Shear MK, Schulberg HC: Anxiety disorders in primary care. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 59(2 suppl A):A73-A85, 1995Google Scholar

8. Kates N: Psychiatry and family medicine: sharing care [editorial]. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:913-914, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Kates N, Craven MA, Crustolo AM, et al: Sharing care: the psychiatrist in the family physician's office. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:960-965, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kates N, Crustolo AM, Nikolaou L, et al: Providing psychiatric backup to family physicians by telephone. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:955-959, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar