State Health Care Reform: Mental Health Parity for Children in California

After the election of a new Democratic governor, Gray Davis, in 1998, California's state legislature enacted mental health parity in 1999, becoming the tenth and final state legislature to do so that year. California's mental health parity law requires individual and group insurance plans to provide coverage for the diagnosis and medically necessary treatment of nine severe mental illnesses and serious emotional disturbances for children under the same terms and conditions that apply to physical illnesses—maximum lifetime benefits, copayments, and deductibles. Medical necessity criteria allow the health plan to determine treatment options for the nine disorders. Mental health services that must be covered include outpatient services, inpatient hospital services, partial-hospitalization services, and prescription drugs, if the plan includes drug coverage. California does not allow exemptions for small businesses or for businesses whose projected cost from parity exceeds a certain percentage. In this column we focus on California's unique decision to include mental health parity for children with serious emotional disturbances.

The need for a children's provision

In general, "parity" is a requirement that a health plan, insurer, or employer provide coverage for mental health care that is "equal" to that provided for physical health care (1). Historically, employers and insurers have placed more restrictive limits on access to the treatment of mental illness than physical illness. Proponents of parity often cite children as one of the key populations for whom mental health benefits have been limited. In 1982 Knitzer (2) wrote that as many as two-thirds of the three million children in the United States who had serious emotional disturbances were not getting the services they needed.

Theoretically, parity has the potential to greatly expand children's benefits. In families with private insurance, the children usually have comprehensive physical health benefits; with parity, their mental health benefits would be "on par" with their physical health benefits. However, in reality most states have inadvertently designed their parity statutes in a way that excludes children's coverage.

In an effort to reduce the cost of parity, lawmakers are narrowing the definition of mental illness. Instead of mandating coverage for all mental disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as mental health legislation has traditionally done, states are typically providing parity for three to 15 mental disorders. For example, Hawaii includes parity for only three mental disorders—schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder—whereas Louisiana provides parity for nine disorders—schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, autism, panic disorder, anorexia or bulimia nervosa, and posttraumatic stress disorder.

Given that the symptoms and course of mental disorders are often very different for children than adults, it is almost impossible to make a diagnosis for a child by using a limited set of mental disorders (3). In essence, children often do not meet the criteria for a "parity diagnosis" and are therefore ineligible for parity benefits. We describe how lawmakers in California were able to include children's benefits in the parity statute.

Parity, take 1

The regulation of mental health insurance is not new to California. Since 1983 California has mandated that health insurers and employee benefit plans offer coverage for mental health services. In 1986 Assemblyman Bruce Bronzan (D-Fresno) introduced AB2752, a bill that required parity in copayments for all mental health services, including children's; a minimum benefit of ten visits; and a $100,000 lifetime limit for mental health coverage. The bill was vetoed by Republican Governor George Deukmejian. In 1989 Assemblyman Bronzan introduced an identical bill, which was vetoed again by the governor (personal communication, North S, 1999).

However, in late 1989 Bronzan found success with AB1692, requiring disability insurers to offer coverage for five specified biologically based severe mental disorders—schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, delusional depression, and pervasive developmental disorder—under the same unspecified terms and conditions applied to all other mental disorders. This was the first time state legislators had crafted a bill that addressed mental disorders by diagnoses.

In 1997 the California Alliance for the Mentally Ill (CAMI) and the California Psychiatric Association (CPA) drafted AB1100, which required health plans, insurers, and employers to provide coverage for the diagnosis and medically necessary treatment of seven biologically based severe mental illnesses under the same terms and conditions applied to other medical conditions. The seven disorders were bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depression, panic disorder, autism, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Parity was required for outpatient services, inpatient hospital services, partial hospital services, prescription drugs if the plan contract included drug coverage, maximum lifetime benefits, copayments, and deductibles. Assemblywoman Helen Thomson (D-Davis) and Senator Don Perata (D-Oakland) became the bill's lead proponents. Thomson had just retired after 20 years as a psychiatric nurse, and her husband—a psychiatrist—was a former president of the CPA. Perata, a former county health supervisor, had extensive experience in mental health.

In the Assembly insurance committee, Thomson offered an amendment to include serious emotional disturbances among children, arguing that children in California were greatly in need of services. That committee did not object, but the Senate committee on insurance argued that the term "severe emotional disturbance of children" was vague and that requiring mental health services for children was costly. Ultimately the Senate committee defined severe emotional disturbance on the basis of the definition used in California's county mental health system, special education programs, and children's health insurance plan.

In the Senate definition, "serious emotional disturbance of a child" referred to a person under the age of 18 years having one or more mental disorders as identified in the most recent edition of the DSM, other than a primary substance use disorder or developmental disorder, that results in behavior that is inappropriate to the child's age according to expected developmental norms and meets one or more of the following criteria: as a result of the mental disorder, the child has substantial impairment in at least two of four areas: self-care, school functioning, family relationships, or ability to function in the community; the child is at risk of removal from the home or has already been removed from the home; the mental disorder and impairments have been present for more than six months or are likely to continue for more than one year without treatment; the child displays one of the following: psychotic features, risk of suicide, or risk of violence due to a mental disorder; or the child meets special education eligibility requirements.

This definition is based on functional definitions rather than diagnostic criteria alone. To qualify for parity, a child in California must meet the criteria for any disorder in the DSM-IV and satisfy certain impairment criteria. The Mental Health Association of California, an advocacy group, helped choose the language by arguing that the definition of mental illness should focus on a child's ability to function rather than on the child's diagnosis (personal communication, Selix R, 1999).

In 1998, in response to Republican Governor Pete Wilson's threats to veto the bill, Perata offered amendments on the Senate floor to narrow the coverage of children's mental illness. Initially, the definition of serious emotional disturbance of children was amended to include only children who had psychotic symptoms or substantial functional impairment. However, in response to cost concerns, coverage for children was eliminated altogether. This version passed both the Assembly (44 to 10) and the Senate (21 to 5) in August 1998. Despite a flurry of last-minute amendments, Governor Wilson vetoed the bill, arguing that it was "too broad" and would drive up the cost of health insurance, making coverage unaffordable to many Californians.

Parity, take 2

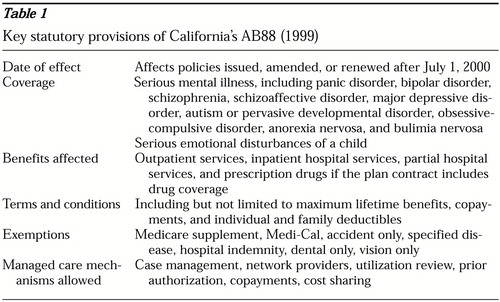

In December 1998 Assemblywoman Thomson introduced AB88 (Table 1), which was almost identical to the introduced version of AB1100. The bill defined "severe mental illnesses" as consisting of the seven diagnoses used in AB1100 with three additions: borderline personality disorder, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa. Thomson again included coverage for serious emotional disturbances of children as originally written in AB1100. The sponsors planned to use a strong antidiscrimination argument to convince other legislators that it was morally wrong not to require equal insurance for children (4). No amendments of the children's provision were introduced, and AB88 passed the Senate (31 to 6) as well as the Assembly (62 to 12). Governor Davis signed the bill into law on September 27, 1999.

Passing a children's parity provision

The passage of mental health parity in California, including a unique children's provision, was the result of a long-term repeated battle among organized business, indemnity insurance and health plan interests, and a well-organized mental health advocacy coalition. Supporters of mental health parity formed the California Coalition for Mental Health, composed of 32 organizations and led by CAMI, the CPA, and the Mental Health Association of California. The coalition focused its lobbying effort around two themes: that parity is affordable and that parity is "the right thing to do" because it does not allow insurers to discriminate against vulnerable populations.

When a children's parity provision was first proposed under AB1100, debate about cost ultimately led to the removal of the provision from the bill. However, debate about the children's provision in AB88 was minimal. Paradoxically, the veto of AB1100 paved the way for and gave momentum to AB88. Legislators were now familiar with the concept of a children's provision, and more data from states with comprehensive parity provisions were available.

CAMI played a major role in showing that a children's provision did not significantly raise the cost of limited parity. For example, on the basis of Roland Sturm's 1997 JAMA article (5) stating that premiums would increase by less than $1 per month under comprehensive parity in a managed care system, CAMI organized a campaign in which 5,000 people each sent the governor $1 with a letter of support for parity. This campaign was important, because comprehensive parity includes coverage for all mental disorders at any age. CAMI argued that a children's provision would be less costly, given that it provides parity for all mental disorders only for those under the age of 18 years (6).

The year before AB88's passage saw a wave of school violence by children that was found to have resulted partly from untreated mental illnesses. With the increase in public awareness about the need to fund children's mental health services, state legislators and Governor Davis signaled an interest in increasing access to children's mental health services. In addition, numerous studies were emerging that linked teenage violence with poor access to mental health services (7).

The election of a new Democratic governor was perhaps the most simple and significant factor that prevented the children's provision from being amended. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal at the time of the Wilson veto, candidate Gray Davis stated that he would sign AB1100, including the children's provision (8). This statement became a rallying cry for AB88—proponents knew that they had bipartisan support in both chambers, as was the case with AB1100, and that the only barrier to passage was getting the governor's signature. Hence they strategically kept the bill identical to AB1100 to remind Governor Davis of his campaign commitment.

Opponents of parity argued that a children's provision was unnecessary and duplicative. The California Mental Health Department already covers children with severe emotional disturbances through several state programs, including Medi-Cal, a special education program, and a children's health insurance plan. Children in California with severe emotional disturbances are considered to be handicapped for the purposes of special education in both federal law—the Handicapped Children's Act (PL 94-142)—and California law—AB3632 (government code, title1, division 7, section 7570). The state is required to provide, at no charge to the family, counseling and related services necessary for the child to benefit from special education.

However, proponents argued that the population of children who need services is growing and that finding appropriate mental health care for a child with a severe emotional disturbance is difficult—the network of public programs in California faces a lack of money and human resources (9). Reports estimate that in Los Angeles County alone, only 5.5 percent of children in need are receiving adequate public mental health services (10). In addition, recent studies of services in Los Angeles County showed that up to 55 percent of the county's resources were allocated to special education students under AB3632 and that most of these students were white adolescents whose parents had private insurance with limited mental health benefits (10). Clearly, advocates argued, parity would benefit these families.

Supporters also criticized the complexity of the state system. For example, under the state's Healthy Families program, an enrolled child must first receive a diagnosis of severe emotional disturbance from his or her health plan provider and then be referred to a county clinic. If a county provider also makes a diagnosis of severe emotional disturbance, treatment becomes the responsibility of the state. Mental health care is provided at the county center, and medical care is still provided by the health plan. To date, the rate of mental health referrals has been extremely low, partly because of the disintegration of the state health care system. Under AB88, health plan providers would provide both physical and mental health services. AB88's children's coverage was seen as a way to shift costs back to private plans, shorten the referral process that is required for entering the public system, and allow county clinics to focus on serving indigent persons.

California and other states with children's parity

As of December 2000, 31 states had some form of parity legislation. However, only four states mandated broader children's coverage than California's—Vermont, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Maryland. Three states—Indiana, New Mexico, and Minnesota—left the definition of mental illness up to the health plan, which could imply broader coverage than California's.

These states cover any diagnoses in the DSM-IV or ICD-10, regardless of the child's functioning. Three other states—Connecticut, Utah, and Kentucky—mandate broad coverage for adults but exclude many children's diagnoses. Two states—Georgia and Missouri—include parity for all memtal disorders in the DSM-IV or ICD-10, but give employers the choice of whether to provide insurance at all. In the remaining states with parity, a child must be diagnosed as having one of a limited set of DSM-IV disorders that are specifically listed in the parity statute. Examples of disorders that are often diagnosed in childhood and that are covered by states are autism, childhood depression, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa. In April 2000 Massachusetts became the second state to enact a separate children's provision for the treatment of mental, behavioral, and emotional disorders.

Conclusion

The key policy issues of parity in California have in some ways just begun to be addressed. How managed behavioral health care plans define what is "medically appropriate or necessary," rather than parity itself, will ultimately determine how children's benefits are expanded. How existing programs-for example, the Healthy Families program-work with county programs and private insurers is also fundamental to parity's success. The next challenges are implementation of the statute's provisions by managed care and evaluation of the impact of a children's provision on cost, utilization, and access.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant MH-18828-11 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Richard M. Scheffler at the Center for Mental Health Services Research at the University of California, Berkeley.

Dr. Peck is a resident in internal medicine at Stanford University Hospitals and was formerly a research associate at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health. Send correspondence to her at the Stanford University Department of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, S101 (m/c 5109), Stanford, California 94305 (e-mail, [email protected]). Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., and Colette Croze, M.S.W., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Key statutory provisions of California's AB88 (1999)

1. National Advisory Mental Health Council: Parity in Coverage of Mental Health Services in an Era of Managed Care: An Interim Report to Congress. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, 1997Google Scholar

2. Knitzer J: Children's mental health: The advocacy challenge, in Advocacy on Behalf of Children With Serious Emotional Problems. Edited by Friedman R, Duchnowski A, Henderson E. Springfield, Ill, Thomas, 1989Google Scholar

3. Taylor E: Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of children with serious mental illness. Child Welfare 77:311-332, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

4. Yoder S: Thomson's mental health parity legislation passes Senate insurance committee. Press Release, Jul 15, 1999. Available at http://democrats.assembly.ca.gov/members/a08/Google Scholar

5. Sturm R: How expensive is unlimited mental health care coverage under managed care? JAMA 278:1533-1537, 1998Google Scholar

6. California Alliance for the Mentally Ill home page. Available at www.cami.org (accessed Oct 27, 1999)Google Scholar

7. Ellickson P, Saner H, McGuigan K: Profiles of violent youth: substance use and other concurrent problems. American Journal of Public Health 87:985-999, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Benson M: Capitol focus: how Davis and Lungren view some of the thorniest legislation. Wall Street Journal, Sep 23, 1998, p CA1Google Scholar

9. Stroul B: Children's Mental Health: Creating Systems of Care in a Changing Society. Baltimore, Brookes, 1996Google Scholar

10. McGuire J: AB3632: mental health entitlement for special education students in California: aspects of the Los Angeles experience. Journal of Mental Health Administration 23:207-216Google Scholar