An Eight-Year Longitudinal Comparison of Clinical Course and Characteristics of Social Phobia Among Men and Women

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Social phobia is a chronic disorder with a higher prevalence among women than men. Data from an eight-year longitudinal study were analyzed to investigate the course of social phobia and to explore potential sex differences in the course and characteristics of the illness. METHODS: Data were analyzed from the Harvard/Brown Anxiety Research Program, a naturalistic, observational study begun in 1989 in which patients with social phobia are assessed every six to 12 months. Treatment was observed but not prescribed by the program personnel. Data on comorbidity, remission, and health-related quality of life were collected for 176 patients with social phobia. RESULTS: Only 38 percent of women and 32 percent of men experienced a complete remission during the eight-year study period, a difference that was not significant. A larger proportion of women than men had the generalized form of social phobia, although the difference was not significant. Women were more likely to have concurrent agoraphobia, and men had a higher rate of comorbid substance use disorders. Social phobia had a more chronic course among women who had low Global Assessment of Functioning scores and a history of suicide attempts at baseline than among men who had these characteristics. Health-related quality of life was similar for both men and women, except that women were slightly but significantly more impaired in household functioning. CONCLUSIONS: The chronicity of social phobia was striking for both men and women. Although remission rates did not differ significantly between men and women, clinicians should be alert to the fact that women with poor baseline functioning and a history of suicide attempts have the greatest chronicity of illness.

Anxiety disorders are widespread among both men and women. The National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), in which 8,098 people were interviewed, found that among the various anxiety disorders the most common diagnosis was social phobia, with a lifetime prevalence rate of 15 percent among women and 11 percent among men (1). The earlier Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study, in which 18,572 people were interviewed, found more modest rates for social phobia—2.3 percent among men and 3.2 percent among women (2). Rates in both studies indicate a gender ratio of 1 to 1.4.

Several reports have described characteristics of social phobia among patients with this disorder. Neither the NCS nor the ECA study reported sex differences in the specific fears related to social anxiety, although the rates of fears in general have been found to be higher among women (2,3). In some clinical cohorts (4), but not all (5), women have reported greater severity of social fears and, in particular, greater severity of several performance fears.

Most researchers agree that social phobia is a chronic illness (6,7). According to retrospectively collected data, the illness has a mean duration of about 25 years (6,7). Few studies have investigated potential sex differences in clinical course. One epidemiological study did not find any differences between men and women in age at onset of social phobia or duration of illness (2). However, that study used a cross-sectional design to evaluate the course of illness.

Interestingly, differences between men and women have been found in the clinical course of posttraumatic stress disorder (8,9) and panic disorder (10) but not generalized anxiety disorder (11,12). Thus the prospective assessment of the course of illness can reveal meaningful differences between men and women and can more fully describe the burden associated with these illnesses.

Understanding the variables that predict the clinical course of social phobia can guide clinicians in their treatment plans. In previous work, we found that the clinical course for patients with social phobia did not differ between the generalized and specific forms of social phobia (13). However, we found that patients with generalized anxiety disorder who had a comorbid personality disorder and a low Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score were more likely to remain in an episode of illness, which suggests the need for more aggressive treatment for this subgroup of patients (12). A history of avoidant personality disorder, which was found to be a predictor of generalized anxiety disorder (12), may be a potent predictor of the clinical course of social phobia. The combination of comorbid avoidant personality disorder and generalized anxiety disorder is believed to be the most severe form of an avoidant disorder (14). No studies have examined how these illness characteristics might differ between men and women with social phobia.

The Harvard/Brown Anxiety Research Program, begun in 1989, has developed a data set that is well suited to investigating possible sex differences in characteristics and course of illness among patients with social phobia, because patients are assessed at relatively short intervals—six to 12 months—over many years. Data on symptoms, remission, health-related quality of life, and treatment for eight years of follow-up are now available. The study is observational, and patients do not receive treatment from program personnel.

Using data from eight years of prospective follow-up of patients in the program, the study reported here investigated whether there were sex differences in the subtype of social phobia (generalized versus nongeneralized), health-related quality of life, course of illness, and selected predictors of remission. On the basis of previous work with patients who have social phobia and patients who have other anxiety disorders, we hypothesized that generalized social phobia would be more prevalent among women, that women would have a more chronic course of illness, and, because of these differences, that women would have greater impairments in health-related quality of life. We also hypothesized that avoidant personality disorder and lower GAF scores would be associated with a lower likelihood of remission among women than among men.

Methods

The Harvard/Brown Anxiety Research Project is an observational, longitudinal study of patients with target anxiety disorders—panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder. Diagnoses are based on DSM-III-R criteria (11,15,16). Patients in the program were enrolled from psychiatric clinics at 11 hospitals in the Boston area and in central Massachusetts beginning in 1989. The exclusion criteria were minimal so that patients seen in usual practice would be included. Patients under 18 years of age and those who were diagnosed as having an organic mental disorder or psychosis in the six months before intake were excluded.

Psychiatric evaluation

The intake interview was comprehensive. It included selected items from the Personal History of Depressive Disorders (Hogarty G, Larkin BH, Hirschfeld RM, unpublished manuscript, 1980); the nonaffective disorders section and the psychosis screen of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, Patient Version (SCID-P) (17); and the affective components of the Research Diagnostic Criteria Schedule for Affective Disorders-Lifetime (SADS-L) (18). Overall ratings of health were assessed with the GAF scale. The subtype of social phobia was based on DSM-III-R criteria—that is, a diagnosis of generalized social phobia required that the patient experience phobia in most social settings.

Patients had follow-up evaluations at six-month intervals for the first two years and then annually thereafter. The instrument used was the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (LIFE-UP) (19), which gathered information about the presence of specific symptom criteria, overall morbidity, treatment, co-occurring general medical and psychiatric illnesses, and psychosocial functioning.

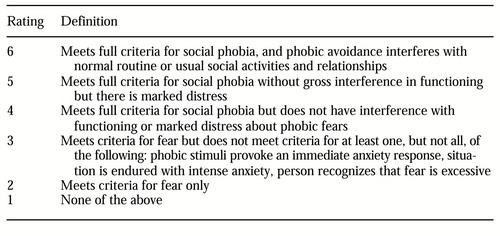

Psychiatric status ratings

The LIFE-UP assesses psychopathology using a 6-point psychiatric status rating that is scored on a month-by-month basis at each interview. A psychiatric status rating of 6 indicates that the patient meets all DSM-III-R symptom criteria for social phobia and also has major functional impairment. If a patient is asymptomatic, a rating of 1 one is assigned. Table 1 presents definitions of the ratings.

Interrater reliability and validity

The clinical interviewers underwent six months of training. Interrater reliability was monitored regularly by review and comparison of raw data with an interview summary. Each month, one videotaped interview was evaluated for each interviewer to control for drift. The videotape was rated by independent monitors who met with the interviewer to discuss ratings.

Three studies to assess interrater reliability, subject recall, and validity of the LIFE-UP psychiatric status ratings were conducted with program participants (20). Median intraclass correlation ranges for psychiatric status ratings were as follows: panic disorder, .67 to .88; agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder, .49 to .64; social phobia, .75 to .86; major depressive disorder, .73 to .74; generalized anxiety disorder, .78 to .86; and GAF score, .72 to .77.

The long-term test-retest reliability of patients' recall over a one-year period was examined, and excellent reliability was found for patients with social phobia (.89). The reliability for patients with the other disorders of interest and for patients with major depressive disorder was very good to excellent—.89 to 1. An independent examination of external validity was conducted. It compared the summed psychiatric status ratings and the GAF scores and found a significant inverse correlation (-.57; p<.001); that is, lower GAF scores reflected lower functioning and higher psychiatric status ratings indicated greater impairment.

Definition of remission

For this study, full remission was defined as occasional or no symptoms (a psychiatric status rating of 1 or 2) for eight consecutive weeks. Ratings over this period can detect changes in morbidity; use of an eight-week period minimizes transient changes in psychopathological state. Partial remission was defined as a decrease in symptoms to a psychiatric status rating of 3 for the same time interval.

Patients were considered to be experiencing an episode of social phobia at intake if they met all the criteria for social phobia at any point during the six months before intake (a psychiatric status rating of 5 or 6) and did not meet all the criteria for remission outlined above. Use of these parameters meant that some patients who were considered to be experiencing an episode of social phobia at intake (a psychiatric status rating above 2) may not have met all the criteria for social phobia at intake because their symptoms had not fully remitted in the previous six months. These patients may be considered as experiencing only partial remission.

Clinical correlates

The intake interview gathered information about marital status (married or living together; divorced, widowed, or separated; or never married), the quality of the relationship with the spouse, satisfaction with life, socioeconomic status, and gender. Satisfaction with life and quality of relationships were rated on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 indicating the lowest level of satisfaction. Severity of illness was determined from the intake GAF score. The combination SCID and SADS-L was used to identify the presence of other axis I disorders and to record the duration of illness, age at onset of illness, and age at intake. The Personality Disorders Evaluation (21) identified the presence of axis II disorders. These covariates were used in a comparison of clinical correlates in men and women.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS version 6.07. PROC FREQ, PROC NPAR1WAY, PROC TTEST, and PROC LIFE TEST were used. Longitudinal data were analyzed with standard survival analysis techniques (21). Kaplan-Meier life tables were constructed for time to remission and for time to relapse. Cox regression analysis was applied to continuous variables to identify predictors of remission and relapse.

Subjects

A total of 176 patients in the program had a lifetime diagnosis of social phobia. Of these, 163 patients had at least one follow-up interview, and this group constitutes the sample for the study reported here. A total of 155 of these patients (95 percent) were interviewed at one year, 149 (91 percent) at two years, 137 (84 percent) at three years, 124 (76 percent) at four years, 118 (72 percent) at five years, 112 (69 percent) at six years, 105 (64 percent) at seven years, and 98 (60 percent) at eight years. Data for patients not available for subsequent interviews were censored.

At intake 106 of the 176 patients (60 percent) were female. The mean± SD age at onset of illness for the patients at intake was 14.4±8.3 years (range, three to 51 years) (22). Patients also reported their age when they were first evaluated for a psychiatric disorder; the mean±SD age at first evaluation was 39±11.1 (range, 18 to 69 years).

Personality disorders were relatively common among the patients in the study sample (23). A total of 63 of 144 patients (44 percent) had a concurrent personality disorder. Previous studies of the patients in the program found a high prevalence of axis I disorders—135 of 176 patients (76.7 percent) had another active anxiety disorder (24). The prevalence of axis I disorders of any type ranged from 11 percent to 47 percent.

Results

Demographic characteristics

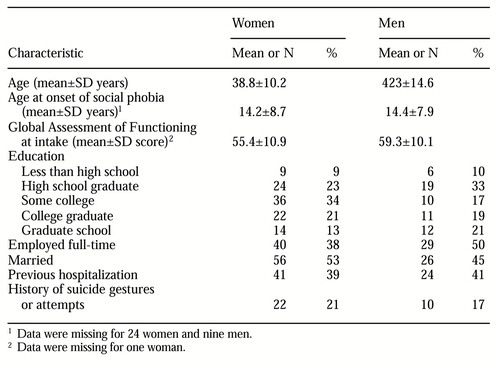

Demographic characteristics of the patients in the sample are presented in Table 2. No significant differences between men and women were found in full-time employment, marital status, level of education, or history of psychiatric hospitalization.

Illness characteristics

The patients' mean GAF scores at baseline indicated no difference between men and women. However, when the score was dichotomized—above 60 and 60 or below—a significantly larger proportion of women had GAF scores below 60 (49 percent of women versus 31 percent of men; χ2=4.7, df=1, p<.03).

At intake, on average, women had more comorbid psychiatric illnesses than men (2.4 comorbid psychiatric illnesses compared with 1.9; t=2.05, df= 161, p<.04). The illnesses most likely to co-occur among women were panic disorder with agoraphobia (50 percent of women and 28 percent of men; χ2=8.02, df=1, p<.005) and simple phobia (24 percent of women and 9 percent of men; χ2=5.75, df=1, p<.017). At intake, men were more likely to have a diagnosis of current or past alcohol or drug abuse or dependence (9 percent of men and 2 percent of women; Fisher's exact test=.159, p=.05).

A previous study found that a slightly larger proportion of women than men had generalized social phobia (56 percent and 47 percent) (22). In addition, a smaller proportion of women had the specific form of social phobia (44 percent versus 53 percent). However, neither difference was statistically significant.

Health-related quality of life

No significant differences were found at baseline between men and women in their satisfaction with their relationships with their spouse, children, or friends. Women had a higher mean score than men on household functioning (2.5 compared with 2.1; t= 2.47, df=174, p=.015), indicating more impaired functioning among women.

Course of illness

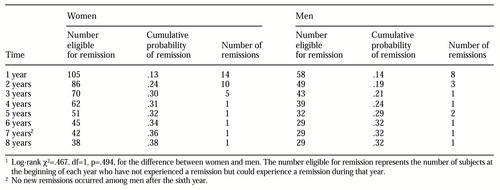

Table 3 presents prospective data on the probability of full remission among men and women. Complete remission required a psychiatric status rating of 1 or 2. As Table 3 shows, the likelihood of full remission was small for both men and women. At one year, only 13 percent of the women and 14 percent of the men had experienced a remission. By four years, the rates of remission for women and men were 31 percent and 24 percent, respectively. After eight years of prospective follow-up, 38 percent of women and 32 percent of men were in full remission from social phobia, which was not a statistically significant difference.

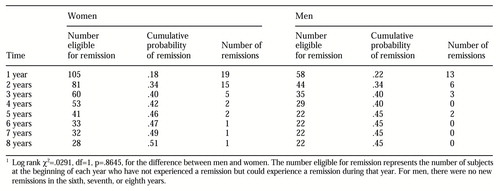

Data on remission from social phobia were reanalyzed to also include patients who experienced partial remission (a psychiatric status rating of 3 or less). Table 4 shows the probability of partial remission. Suprisingly, remission rates were only slightly higher at one year—18 percent for women and 22 percent for men. At eight years, partial remission rates hovered around 50 percent; a slightly higher proportion of women experienced remission (51 percent compared with 45 percent), but the difference was not statistically significant.

Predictors of remission

Given the low rate of remission, we combined data for patients in both full and partial remission for analysis. Because of the low rate, we had to limit the number of predictor variables, and therefore we investigated covariates that previous research suggested would be salient. They included baseline GAF score, history of avoidant personality disorder, and history of a suicide attempt.

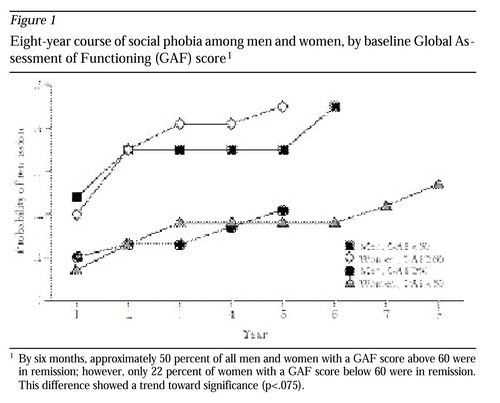

An analysis of baseline GAF scores stratified by gender and illness severity (50 and below or above 60) showed that women in the lowest GAF strata were least likely to experience a remission (Figure 1). At six months, approximately 50 percent of all men and women with a GAF score above 60 were in remission; however, only 22 percent of women with a GAF score below 60 were in remission. This difference showed a trend toward significance (p<.075). We explored whether women in the low GAF group had any comorbid illness that would explain this finding. We found that patients who were not in remission were more likely to have agoraphobia than patients in remission (24 of 34 patients versus 33 of 71 patients; χ2=5.4, df=1, p<.02).

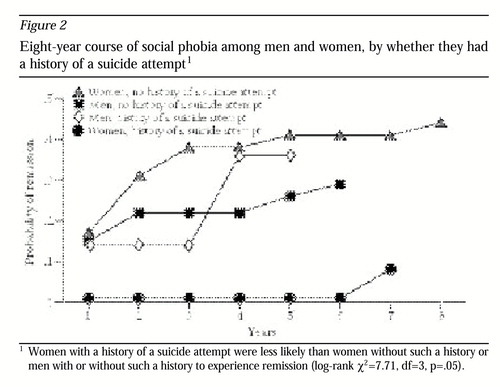

No significant difference between men and women was found in the presence or absence of avoidant personality disorder. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 2, women with a history of suicide attempts were less likely to experience remission than women with no history of suicide attempts or men with or without such a history (log-rank χ2=7.71, df=3, p=.055).

Discussion

During eight years of observation of 163 patients with social phobia, only 38 percent of women and 32 percent of men experienced full remission of the disorder. This finding highlights the chronicity of the disorder and indicates a similar course for men and women.

The results did not support our hypothesis, in that we did not find a sex difference in remission rates even though a larger, but not significantly larger, proportion of women than men had generalized social phobia (52 percent and 47 percent). These results for social phobia differ from those for posttraumatic stress disorder, which shows a more chronic course in women (9). Similarly, panic disorder is often more chronic among women, because women are more likely to have agoraphobia in addition to panic disorder (10,24). On the other hand, findings for social phobia are similar to those for generalized anxiety disorder, a condition that has a similar course among men and women (11,12).

More detailed analyses in this study identified which groups of women were the least likely to experience remission from social phobia. We found a trend for women with the lowest baseline GAF scores to be less likely than men with equivalent GAF scores to experience remission. In addition, women with a history of suicide attempts were significantly less likely than men with a history of suicide attempts to experience remission. In subsequent analyses, we found that women in the poor outcome group were more likely to have agoraphobia than those who experienced remission (10). Agoraphobia, which is associated with a longer episode of illness among patients with panic disorder, may also contribute to the duration of an episode of social phobia. Over time it may be possible to investigate the relationship between other clinical characteristics and gender; however, in this study the number of variables we could examine was limited by the low rate of remissions.

As has been shown previously (23), demographic characteristics among men and women with social phobia were similar. These findings replicate those of Turk and colleagues (4). The comorbidity patterns among men and women in the study reported here—a higher rate of substance use disorders among men and a greater degree of concurrent panic with agoraphobia and simple phobia among women—are similar to patterns found in epidemiological samples (1,2), suggesting that a diagnosis of social phobia does not neutralize these sex differences. Interestingly, we found no sex differences in comorbid major depressive disorder even though epidemiological studies show that twice as many women report this disorder (26,27). Apparently, social phobia is such a potent risk factor for major depressive disorder that it neutralizes the difference between men and women that is typically observed.

Finally, we hypothesized that women would experience more functional impairment than men, largely because their phobia was more likely to be generalized. Women did show greater impairment than men in household functioning. This finding may reflect overall poorer functioning because it is socially acceptable for women not to work outside the home, and measures of domestic work impairment may therefore be more salient for women.

This investigation had several limitations. First, only symptoms that are part of the DSM-III-R criteria were measured, and other phobic situations were not examined. Thus we were not able to ascertain whether fears not addressed by DSM-III-R criteria differed between men and women. Second, because subjects were recruited from psychiatric practices, they most likely represent a more ill group of patients with social phobia. This idea is supported by the high rate of past psychiatric hospitalization among patients in the cohort. Third, despite a substantial cohort size and eight years of follow-up, few patients in the study experienced a remission. Thus the estimates of differences should be viewed with caution. The strengths of the study include the careful diagnostic evaluation, the longitudinal design, and the extended follow-up period.

Conclusions

This longitudinal, prospective, observational investigation confirmed the chronicity of social phobia found in cross-sectional studies (7). However, no differences between men and women in clinical course were found. Women with low baseline GAF scores and a history of suicide attempts were less likely than males with these characteristics to experience remission. Women also experienced poorer functioning at home than men, but no differences were found in other domains of functioning. Clinicians need to be alert to the fact that women with social phobia who have low GAF scores, a history of suicide attempts, or comorbid agoraphobia are likely to have a more chronic clinical course.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Yonkers is supported by grant K08-MH-01648-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Dr. Keller and Ms. Dyck are supported by NIMH grant MH-51415. Support was also provided by the Global Research on Anxiety and Depression Network through an unrestricted educational grant made possible by Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Yonkers is associate professor in the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine, 142 Temple Street, Suite 301, New Haven, Connecticut 06510 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Dyck is research associate and Dr. Keller is chair of the department of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

Figure 1. Eight-year course of social phobia among men and women, by baseline Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score1

1 By six months, approximately 50 percent of all men and women with a GAF score above 60 were in remission; however, only 22 percent of women with a GAF score below 60 were in remissionThis difference showed a trend toward significance (p<.075).

Figure 2. Eight-year course of social phobia among men and women, by whether they had a history of a suicide attempt1

1 Women with a history of a suicide attempt were less likely than women without such a history or men with or without such a history to experience remission (log-rank χ2 =771, df=3, p=.05).

|

Table 1. Psychiatric status scale for social phobia

|

Table 2. Characteristics of 163 participants in a study of social phobia in men and women

|

Table 3. Probability of full remission among women and men with social phobia in an eight-year longitudinal study1

1 Log-rank χ2 =467, df=1, p=.494, for the difference between women and men. The number eligible for remission represents the number of subjects at the beginning of each year who have not experienced a remission but could experience a remission during that year.

|

Table 4. Probability of partial remission among women and men with social phobia in an eight-year longitudinal study1

1 Log rank χ2 =0291, df=1, p=.8645, for the difference between men and women. The number eligible for remission represents the number of subjects at the beginning of each year who have not experienced a remission but could experience a remission during that year. For men, there were no new remissions in the sixth, seventh, or eighth years.

1. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bourdon KH, Boyd JH, Rae DS, et al: Gender differences in phobias: results of the ECA community survey. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2:227-241, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Curtis GC, Magee WJ, Eaton WW, et al: Specific fears and phobias: epidemiology and classification. British Journal of Medicine 173:212-217, 1998Google Scholar

4. Turk CL, Heimberg, Richard G, et al: An investigation of gender differences in social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 12:209-223, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Edelmann RJ: Dealing with embarrassing events: socially anxious and non-socially anxious groups compared. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 24:281-288, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. DeWit DJ, Ogborne A, Offord DR, et al: Antecedents of the risk of recovery from DSM-III-R social phobia. Psychological Medicine 29:569-582, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kessler RC, Stein MB, Murray B, et al: Social phobia subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:613-619, 1998Link, Google Scholar

8. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P: Traumatic events and traumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:218-222, 1991Google Scholar

9. Breslau N, Davis G: Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: risk factors for chronicity. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:671-675, 1992Link, Google Scholar

10. Yonkers KA, Zlotnick C, Allsworth J, et al: Is the course of panic disorder the same in women and men? American Journal of Psychiatry 155:596-602, 1998Google Scholar

11. Yonkers KA, Massion A, Warshaw M, et al: Phenomenology and course of generalised anxiety disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:308-313, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Yonkers K, Dyck I, Warshaw M, et al: Factors predicting the clinical course of generalised anxiety disorders. British Journal of Medicine 176:544-550, 2000Google Scholar

13. Reich J, Goldenberg I, Vasile R, et al: A prospective follow-along study of the course of social phobia. Psychiatry Research 54:249-258, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Greist JH: Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: psychotherapies, drugs, and other somatic treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51(suppl 8):44-50, 1990Google Scholar

15. Keller MB, Yonkers KA, Warshaw MG, et al: Remission and relapse in subjects with panic disorder and panic with agoraphobia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:290-296, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Massion A, Warshaw M, Keller M: Quality of life and psychiatric morbidity in panic disorder versus generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:600-607, 1993Link, Google Scholar

17. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R: Personality Disorders (SCID-II, Version 1.0). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

18. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS-L). Archives of General Psychiatry 35:837-844, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, et al: The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry 446:540-548, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Warshaw MG, Keller MB, Stout RL: Reliability and validity of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation for assessing outcome of anxiety disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research 28:531-545, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Loranger A, Susman V, Oldham J, et al: The Personality Disorder Examination: a preliminary report. Journal of Personality Disorders 1:1-13, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Kalbfleish JG, Prentice RL: The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York, Wiley, 1980Google Scholar

23. Weinshenker NJ, Goldenberg I, Rogers MP, et al: Profile of a large sample of patients with social phobia: comparison between generalized and specific social phobia. Depression and Anxiety 4:209-216, 1996-1997Google Scholar

24. Dyck IR, Phillips KA, Warshaw MG, et al: Patterns of personality pathology in patients with generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder with and without agoraphobia, and social phobia. Journal of Personality Disorders 15:60-71, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Yonkers KA: Recognition and treatment of anxiety disorders in women, in Textbook of Women's Health. Edited by Wallis LA, Kasper AS, Brown W, et al. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1998Google Scholar

26. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, et al: Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey: I. lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders 29:85-96, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al: Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA 276:293-299, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar