Psychopharmacology: Cardiac Effects of Antipsychotic Medications

Soon after their introduction, phenothiazines were associated with rare unexplained sudden deaths, often of young adults. Combinations of drugs were frequently involved, usually but not always at high dosages, and about half the episodes occurred within a month after the drug was introduced or the dosage was increased. However, the absolute risk involved with the use of various antipsychotic agents was unknown, and it is probable that many deaths resulting from their use, especially those involving older patients, went unrecognized.

Use of electrocardiograms (ECGs) to monitor the safety of pharmacotherapy is at best sporadic in psychiatric clinics; often equipment is not available, particularly for the increasing numbers of patients treated in the community (1). Because neuroleptics affect cardiac repolarization, in keeping with their quinidine-like action, QTc has been found to be an accurate indicator of their effect on the heart (2).

The QT interval, measured from the earliest onset of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave, represents the duration of action potential propagation (the QRS complex) and the sum of the duration of ventricular repolarization across the ventricular myocardium (1). QTc is the QT interval corrected for heart rate, and there are different ways of applying this correction, sometimes leading to slightly different results. Generally a QTc longer than 450 milliseconds is of potential concern, and a QTc longer than 500 milliseconds indicates a higher risk of arrhythmia and sudden death.

Although QT interval prolongation is often benign, some patients develop a life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia called torsade de pointes, which is characterized by sinus bradycardia with a prolonged QT interval, interrupted by runs of ventricular tachycardia that may progress to ventricular fibrillation. The clinical spectrum of manifestations of torsade de pointes is quite wide, ranging from asymptomatic palpitations to sudden death. A common manifestation is syncope, sometimes accompanied by myoclonic convulsions due to cerebral ischemia (3).

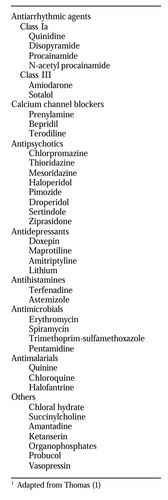

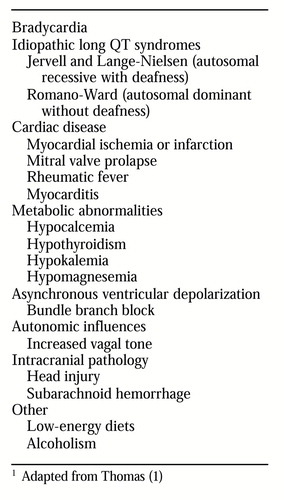

Table 1 lists drugs that can cause this syndrome. They include the class Ia antiarrhythmic agents, the tricyclic antidepressants, and the antipsychotic drugs, particularly the phenothiazines and especially thioridazine. Nonpharmacologic causes are listed in Table 2.

Cardiovascular and ECG effects of antipsychotics

In addition to their effect on cardiac conduction, antipsychotic medications have a negative inotropic effect, reducing cardiac output and lowering blood pressure. It has been suggested that a catastrophic drop in blood pressure might have been responsible for some cases of sudden death, particularly among patients taking high dosages of antipsychotics, although sharp drops in blood pressure and sudden death may also occur with low dosages.

Chlorpromazine and other older conventional antipsychotics are more likely to induce hypotension—and more severe hypotension—than the newer, more selective dopamine antagonists (5). The effects of phenothiazine antipsychotics on cardiovascular function have been well described. Hypotension has been reported to result from alpha-adrenergic blockade, calcium blockade, inhibition of centrally mediated pressor reflexes, and a negative inotropic effect (4).

Among the phenothiazines, thioridazine has been noted for the frequency and severity of its cardiac effects, although it has been used safely with many patients for decades. It is the antipsychotic most frequently cited in cases of drug-induced cardiotoxicity and ECG changes (3). Even at moderate dosages and in otherwise healthy patients, it may cause hypotension, prolong QT intervals, change T wave morphology, and induce prominent U waves, premature ventricular contractions, and ventricular arrhythmias, with related syncope, seizure, and even sudden death. Thioridazine is comparable to quinidine in its antiarrhythmic and arrhythmogenic qualities. Thioridazine and other quinidine-like drugs may produce torsade de pointes (6).

With the exception of mild hypotension, cardiovascular and ECG effects due to haloperidol are rare and usually are associated with high dosages. In one recent report, very high dosages of antipsychotics were associated with cardiac conduction abnormalities, although more moderate dosages appeared safe (7). In 1990 pimozide was reported to have caused 13 deaths among young patients in the United Kingdom who were using dosages in excess of 20 mg a day. The deaths led to changes in dosage recommendations for pimozide; 20 mg of pimozide a day became the maximum recommended dosage (1).

In 1996 sertindole was responsible for 16 deaths from cardiac causes among 2,194 patients who participated in clinical trials. These deaths provided strong evidence to the Food and Drug Administration linking the use of sertindole, which prolongs the QT interval, to the development of torsade de pointes. As a result, sertindole was not marketed in the United States, and postmarketing surveillance led to its withdrawal from the European market (8).

In a recent studies conducted by Pfizer, the QTc-prolonging effect of a daily dose of 160 mg of ziprasidone was found to be about 10 milliseconds greater than those of four other antipsychotics (haloperidol, quetiapine, risperidone, and olanzapine) in moderate dosages and 10 milliseconds less than that of a 300 mg daily dose of thioridazine (Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, unpublished data, 2000). It is not known how the use of higher dosages or polypharmacy would affect these results.

Recommendations

Although torsade de pointes is generally self-terminating and generates few hemodynamic symptoms, this arrhythmia must be considered potentially life-threatening because of its tendency to recur and to deteriorate into ventricular fibrillation. Hence adequate monitoring should be implemented early when a drug is introduced that may prolong the QT interval (9). Treatment of drug-induced torsade de pointes consists of discontinuation of the offending agent and treatment of the arrhythmia, either with electrical atrial pacing or with medications. Treatment is best managed in a medical intensive care unit.

It is especially important to keep in mind that patients with major psychiatric disorders tend to have more risk factors for QT interval prolongation than the general population. The risk factors include treatment with other drugs that also prolong QTc and treatment with concomitant medications that inhibit the cytochrome P-450 enzyme system, leading to elevated serum concentrations of medications that prolong the QT interval.

Another risk factor for patients with major psychiatric disorders is overdose of medication; 30 percent of patients with schizophrenia attempt suicide, and 10 percent of these patients succeed in the attempt; 20 to 55 percent of patients with bipolar I disorder attempt suicide, and 20 percent of these patients succeed. Other elevated risk factors are electrolyte imbalance and a history of ischemic disease.

We recommend that laboratory tests (electrolytes, kidney function, liver function, fasting glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, calcium, and magnesium), an electrocardiogram, vital signs, and weight be obtained for all patients before they begin any antipsychotic medication and at least yearly thereafter. Changes in weight, glucose, and serum lipids associated with the use of some antipsychotic medications may also lead to problems for some patients. Nonspecific T wave changes are commonly seen in the midafternoon; therefore, obtaining ECGs before breakfast may be desirable (9). If the baseline QTc is 450 milliseconds or longer, alternative treatment should be prescribed whenever possible. If the QTc lengthens by 25 percent or more over baseline, the drug involved should be discontinued or the dosage reduced. If hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia are detected, they should also be corrected and closely monitored during therapy (4). ECGs and laboratory tests should be done at least yearly, and more frequently if risk factors are present.

Antipsychotic medications should be chosen in part on the basis of knowledge about preexisting conditions. Just as one may choose not to use ziprasidone for a patient with preexisting cardiac disease, one may choose a medication other than olanzapine or quetiapine for patients with preexisting diabetes or hyperlipidemia. Likewise, one may choose medications other than risperidone for patients with hyperprolactinemia or known sensitivity for developing extrapyramidal symptoms.

The risk of cardiac arrhythmias may be dose related, and low dosages of psychotropic medications should be used whenever possible (10). Because of greater cardiac sensitivity among elderly people, it is advisable to avoid low-potency neuroleptic drugs, such as thioridazine, which produce significantly more cardiac changes than high-potency agents, such as fluphenazine (11).

Atypical antipsychotics have largely supplanted the older, conventional agents, a change that we believe is a beneficial one. However, the notable reduction in extrapyramidal symptoms with these newer agents is not without some cost. Clinicians need to be aware of potentially serious side effects that were given little attention before the introduction of atypical antipsychotics and the concomitant reduction in extrapyramidal symptoms. Prolongation of QT intervals must be added to a growing list of side effects such as weight gain, type II diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and prolactinemia that clinicians must monitor when prescribing these medications.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and the behavioral sciences in the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, 2020 Zonal Avenue, Los Angeles, California 90033. Send correspondence to Dr. Kingsbury (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Simpson is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Medications associated with prolongation of QT intervals1

1 Adapted from Thomas (1)

|

Table 2. Nonpharmacological causes of prolongation of QT intervals1

1 Adapted from Thomas (1)

1. Thomas SHL: Drugs, QT interval abnormalities, and ventricular arrhythmias. Adverse Drug Reactions and Toxicological Reviews 13:77-102, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

2. Warner JP, Barnes TRE, Henry JA: Electrocardiographic changes in patients receiving neuroleptic medication. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 93:311-313, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Sudden Death in Psychiatric Patients: The Role of Neuroleptic Drugs. Task Force Report 27. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

4. Lawrence KR, Nasraway SA: Conduction disturbances associated with administration of butyrophenone antipsychotics in the critically ill: a review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy 17:531-537, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

5. Thompson C: The use of high-dose antipsychotic medication. British Journal of Psychiatry 164:448-458, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Liberator MA, Robinson DS: Torsade de pointes: a mechanism for sudden death associated with neuroleptic drug therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 4:143-146, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

7. Reilly JG, Ayis SA, Ferrier IN, et al: QTc-interval abnormalities and psychotropic drug therapy in psychiatric patients. Lancet 355:1048-1052, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Barnett AA: Safety concerns over antipsychotic drug, sertindole. Lancet 348:256, 1996Google Scholar

9. Faber TS, Zehender M, Just H: Drug-induced torsade de pointes: incidence, management, and prevention. Drug Safety 11:463-476, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Simpson GM, Pi EH, Sramek JJ: Neuroleptic and antipsychotic drugs, in Myler's Side Effects of Drugs: An Encyclopedia of Adverse Reactions and Interactions. New York, Elsevier, 2000Google Scholar

11. Branchey MH, Lee JH, Amin R, et al: High- and low-potency neuroleptics in elderly psychiatric patients. JAMA 239:1860-1862, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar