Insight Into Mental Illness and Child Maltreatment Risk Among Mothers With Major Psychiatric Disorders

Abstract

Objectives: This study examined the relationship between insight into mental illness and current child maltreatment risk among mothers who had a major psychiatric disorder and who had lost custody of a child because of abuse, neglect, or having placed the child at risk of harm. Specifically, a measure of insight was examined in relation to systematically observed parenting behaviors known to be correlated with past child maltreatment and in relation to a comprehensive clinical determination of risk. METHODS: Forty-four mothers who had a major psychiatric disorder were independently rated for their insight into their illness, the quality of mother-child interaction, and the overall clinical risk of maltreatment. RESULTS: Better insight into mental illness was associated with more sensitive mothering behavior and with lower assessed clinical risk of maltreatment. The association remained when mothers with current psychotic symptoms were excluded from the analyses. Better insight did not appear to be associated with past psychotic symptoms, maternal psychiatric diagnosis, or the mother's level of education. CONCLUSIONS: Insight into mental illness may function as a protective factor that influences the risk of child maltreatment in mothers with mental illness. Measures of insight could be usefully incorporated into comprehensive parenting assessments for mothers with psychiatric disorders.

Just as major mental illness can interfere with any social and occupational functioning, it can impair the ability to parent a child (1,2,3,4). In the most extreme cases, this impairment can contribute to a parent's maltreating a child. Clinically, maltreatment encompasses physical abuse—for example, intentional injuries or sexual assault—as well as gross neglect—for example, failure to prevent harm or to provide adequate physical and emotional care (5). Current trends suggest that a growing number of parents with psychiatric disorders are losing custody of their children because of maltreatment (6,7). Biological children of parents with heritable psychiatric disorders may have an elevated genetic vulnerability for developing mental illness under adverse environmental conditions (8) and thus may be particularly susceptible to the effects of abusive or neglectful parenting.

Parents within any given diagnostic category can have parenting skills ranging from excellent to maltreating (2,3,9); therefore, effective methods of assessing parenting capability in the context of mental illness are crucial. Methodologically sound parenting assessment strategies can help mental health caregivers and child welfare workers determine which parent-child dyads are at risk, what specific parenting strengths and weaknesses are present, and what interventions might improve parenting capability. Unfortunately, many of the tools currently used for parenting assessments, such as projective tests, personality profiles, and intelligence tests, were not intended for the purpose of evaluating parenting capability or for this population, and they are not empirically linked with observed parenting behavior (10).

A number of specific, measurable factors are thought to influence parenting capability. Among the most central are realistic expectations about the child (11); an ability to sensitively read and respond to a child's cues (12); history of childhood trauma in the parent (13); parental stress, including stresses related to special needs of the child (14); and social support (15). For parents with a major mental illness, additional illness-related factors such as severity of symptoms, acceptance of treatment, and response to treatment may exert a strong influence on parenting. These factors, in turn, may be strongly influenced by the parent's insight into his or her psychiatric condition. Clear insight into a psychiatric disorder can lead to better recognition of incipient relapse, better acceptance of treatment, and overall improved outcome (16,17,18,19).

Our study was designed to ascertain whether insight into mental illness is specifically associated with observed parenting behavior of mothers with major mental illness.

We focused on a high-risk group: mothers with a major mental illness who had lost custody of their children because of abuse, neglect, or having placed them at risk of harm. This group was chosen because of the compelling need to find useful assessment tools in this context. We hypothesized that the less insight a mother demonstrated into her mental illness, the more problematic her parenting behavior, as exhibited in a standardized parent-child observation, and the higher the risk of child maltreatment, as exhibited in a standardized clinical assessment of maltreatment risk.

Methods

Study participants

The subjects were referred by child welfare workers to the parenting assessment team at the University of Illinois at Chicago between January 1996 and April 1999. All parents who were referred had lost custody of a child as a result of confirmed abuse, neglect, or risk of harm. They were referred for an assessment to determine their current ability to safely parent their child. They had been hospitalized at least once for a DSM-IV (20) psychiatric illness other than substance abuse or dependence and thus struggled with a different level of mental illness than persons who had never been hospitalized.

Of the 118 families who were evaluated by the parenting assessment team, 44 mother-child dyads met the following inclusion criteria for our study: the parent was a woman at least 20 years old, the index child was between eight months and four years of age, and there had been at least weekly contact between the mother and the index child during the one-year period preceding the study. Mothers who met DSM-IV criteria for mental retardation and those who spoke neither English nor Spanish were excluded from the study.

The inclusion criteria were selected to provide a relatively homogeneous population for study. Mothers may have somewhat different parenting issues than fathers, teenage parents may have different issues than older parents, and parenting young children calls for a different set of skills than parenting older children. The population chosen for our study reflects the current priorities of the child welfare system (21). The requirement for at least weekly visits was included to ensure enough parent-child contact for an ongoing parental relationship to have been maintained despite the mother's loss of custody. The study was approved by the institutional review board, and all subjects gave written informed consent to participate.

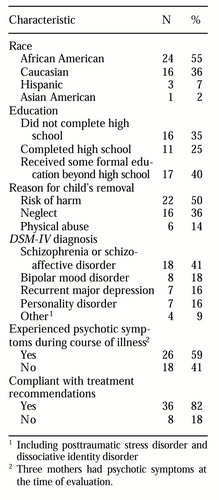

Of the 44 participating index children, half were less than two years old and half were two to four years old; half were male and half female. The mean±SD age of the 44 participating mothers was 32.4±6.3 years, with a range of 20 to 45 years. Additional information about the mothers is provided in Table 1.

Instruments

Measure of insight. Among the tools available to assess insight, the one chosen as optimal for this study was a modified version of the Schedule for Assessment of Insight (23). This scale approaches insight as a multidimensional phenomenon (18). It has been used as a measure of insight in various studies (24), and it is short enough to be practical for use as part of a battery of assessment tools. We modified the scale for use not only with patients with psychotic disorders, as was its original intent, but also for use with other persons with major mental illness. The modified instrument may be obtained from the authors.

In the study reported here, a psychiatrist with prior training in the use of the insight scale independently rated the 44 psychiatric interviews with the mothers. The psychiatrist subsequently completed a written psychiatric evaluation based on the interview and on available records of past evaluations, hospitalizations, and treatment. The written report contained no information about insight into mental illness. A second independent psychiatrist who also had prior training in using the scale rated 20 randomly selected written psychiatric evaluations. The raters had not participated in administering the study tools, and they were fully blinded with regard to each other's ratings and with regard to findings on all study variables. The intraclass correlation statistic, a measure to estimate interrater reliability, was 95.

Measures of parenting risk. The most direct way to determine whether a mother is at risk of further maltreating a child whom she has maltreated in the past would be to have her resume custody of the child and see what happens. However, this option would not be ethically justified, so researchers use less direct but still very useful measures of parenting risk. One effective measure chosen for this study was a direct, systematic observation of maternal behavior. The second measure was a comprehensive multidisciplinary clinical estimation of risk.

We used the Crittenden Care Index (12) as a measure of mother-child interaction quality. This index was specifically developed for use with maltreating families and is appropriate for mothers with children up to four years old. It has been used with families from high-risk backgrounds and different social classes. Index ratings have been found to be highly correlated with mother-child attachment quality, child interactive behavior, and childrearing status—for example, abusing, neglecting, or adequate (12). The index has high interrater reliability among trained raters (kappa=.83 to 90).

The index is obtained by scoring a videotape of a mother-child interaction in a standard observation. The mother and child are asked to play as they usually do at home. The two sit facing each other, with a basket of age-appropriate toys nearby. Their interaction is videotaped for three minutes. The index focuses on seven aspects of parental behavior: facial expression, vocal expression, position and body contact, expression of affection, pacing control, and choice of activity. Each aspect of maternal behavior is scored as insensitive, 0; partially sensitive, 1; or sensitive, 2. The scored items for each aspect of behavior are summed to yield an overall score ranging from 0 to14. A score of 6 or less is considered to be indicative of at-risk parenting.

In our study, the Crittenden Care Index was administered as part of a comprehensive evaluation of parenting competency. It was therefore necessary to ensure that the observational ratings were independent of the clinical estimation of maltreatment risk. To this end, two clinical psychologists who were trained in the use of the index scored all 44 tapes. The raters had not participated in administering any study tools or in making the comprehensive clinical ratings of maltreatment risk (described below). They also had no knowledge of each other's ratings or of any of the study's variables or findings. The interclass correlation between the two raters on the maternal sensitivity scale was .73.

Clinical risk for child maltreatment. A parenting assessment team—a psychiatrist, a psychologist, and a social worker—conducted standardized clinical assessments to estimate the likelihood that a particular mother would abuse or grossly neglect the index child if she were currently the child's primary caregiver. The assessment of each dyad included:

• Clinical interviews, including unstructured and semistructured interviews of the mother and child separately from one another

• Interviews with collateral historians

• Review of records, including psychiatric records, relevant medical records, child welfare agency records, and school reports

• Evaluation of the home setting using a modified Home Observation for the Measurement of the Environment inventory (25)

• Evaluation of parental expectations of the child using the Parent Opinion Questionnaire (11)

• Evaluation of maternal behavior and mother-child attachment quality in the home and in a standard clinical observation (12)

• Evaluation of the effects of the mother's childhood trauma using the Childhood Trauma Interview (26)

• Evaluation of current parenting stressors and mothers' ability to identify and acknowledge stressors using the Parental Stress Inventory (27)

• Evaluation of the mother's current social support for parenting using a modified version of the Arizona Social Support Inventory (29)

• An assessment of the mother's internal representation of her children (29)

• A criminal background check

All the data were gathered and scrutinized according to guidelines described in the Parenting Assessment Team Manual (30) and summarized in a prior publication (31), which also discusses the rationale for the choice of assessment methodology. The assessment team reviewed the data for each case and considered risk factors in relation to protective factors and potential for change. The team then decided by consensus to assign the respondent to a higher or lower risk category for maltreatment. A higher-risk assignment meant that even if the mother was offered interventions, the prognosis for adequate parenting capability in a reasonable time frame was poor. A lower-risk assignment meant that if specific interventions were offered and accepted, there was a reasonable likelihood that the mother could successfully become an effective primary caregiver for her child. The procedure used to make a consensus decision in assigning these categories is comparable to the best-estimate technique (32), which has been used to make DSM-IV axis I and axis II diagnoses and has been shown to have high test-retest reliability.

Data analysis

Spearman's rho for continuous variables and t tests for categorical variables were used to examine associations between insight and other variables. All analyses were conducted with SPSS software.

Results

We found a significant positive correlation between insight score and Crittenden ratings of maternal sensitivity (Spearman's rho=.37, p<.02, one-tailed test). In addition, mothers who had a total Crittenden score of 6 or less—the cutoff used in previous studies for at-risk parenting behavior—had significantly lower insight than mothers whose total Crittenden score was above 6 (t=4.86, df=1, p<.05).

In the clinical assessment, 27 of the mothers (61 percent) were judged to be at higher risk of maltreating their children. The mean±SD insight score for these mothers was 2.78±2.14 (range=0 to 7). For the 17 mothers in the lower-risk category (39 percent), the mean±SD insight score was significantly higher, 5.72±2.23 (range=0 to 7; t=17.9, df=1, p<.01). The mothers' insight scores did not vary significantly with their level of education, psychiatric diagnosis, or whether or not they had psychotic symptoms in the past.

An apparent relationship was found between current psychotic symptoms and low insight. All three mothers who had current psychotic symptoms obtained a low score—1—on the insight scale. However, the relationship between insight and the Crittenden measure (Spearman's rho=.30, p<.05, one-tailed test) and between insight and the comprehensive clinical risk measure (t=15.15, df=1, p<.01) remained significant when these mothers were excluded from the statistical analyses.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study support the hypotheses that lack of insight into mental illness is associated with directly observed problematic parenting behavior as well as with clinically determined risk of child maltreatment. To put these findings in context, insight into illness has been shown to be a predictor of better outcome of illness (33), better adherence to medication and psychosocial treatments (34,35), and better vocational and psychosocial functioning (36). For many mothers, parenting is the social and occupational role they value most (37).

Our findings suggest that insight into illness is not simply a function of educational level or type of psychiatric disorder. Contrary to the findings reported in some studies (38,39), poor insight was not specifically linked to a history of psychotic symptoms, which suggests that the measure can be useful whether or not a parent has had psychosis. Although the three mothers with current psychotic symptoms in our study did appear to have poor insight, the relationship between insight and the two outcome measures remained when these mothers were excluded from statistical analyses.

Child maltreatment results from a multiplicity of factors that interact with each other over time (40). The articulation of factors that contribute to or ameliorate child maltreatment is integral to both assessment and prevention efforts. Overall, the results of this study suggest that insight into illness may act as one important protective factor among mothers with mental illness who are at risk of child maltreatment. Because child maltreatment is multidetermined, insight into illness should not be used as a single measure of risk. However, it may be a valuable measure for mental health and child welfare professionals in comprehensive evaluations of parenting capability among mothers with major psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant R03-MH-058379-01 to Dr. Jacobsen and Dr. Miller. The authors thank Michael Fendrich, Ph.D., Julia Kim, M.A., Andrea Waddell-Pratt, Ph.D., and Charu Raghuvanshi, M.D.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, 912 South Wood Street, MC 913, Chicago, Illinois 60612 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 44 mothers who participated in a study of their insight into their mental illness and risk of child maltreatment

1. Apfel RJ, Handel MH: Madness and Loss of Motherhood: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Long-Term Mental Illness. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

2. Rogosch FA, Mowbray CT, Bogot A: Determinant of parenting attitudes in mothers with severe psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology 4:469-487, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Mowbray C, Oyserman D, Zemenick J, et al: Motherhood for women with serious mental illness: pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:21-38, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Reder P, Lucey C: Assessment of Parenting: Psychiatric and Psychological Contributions. London, Routledge, 1995Google Scholar

5. Carter-Lourensz HJ, Johnson-Powell G: Physical abuse, sexual abuse and neglect, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 6th ed. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1995Google Scholar

6. Nicholson J, Geller JL, Fisher WH, et al: State policies and programs that address the needs of mentally ill mothers in the public sector. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:484-489, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Blanch A, Nicholson J, Purcell J: Parents with severe mental illness and their children: the need for human services integration. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:388-396, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wahlberg K, Wynne L, Oja H, et al: Gene-environment interaction in vulnerability to schizophrenia: findings from the Finnish adoptive family study of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:355- 362, 1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Lyons-Ruth K, Repacholi B, McLeoad S, et al: Disorganized attachment behavior in infancy: short-term stability, maternal and infant correlates, and risk related subtypes. Development and Psychopathology 3:377- 396, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Budd KS, Holdsworth MJ: Methodological issues in assessing minimal parenting competence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 25:2-14, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Azar ST, Robinson DR, Hekimian E, et al: Unrealistic expectations and problem solving ability in maltreating and comparison mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 52:687-691, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Crittenden PM: Relationship at risk, in Clinical Implications of Attachment. Edited by Belsky J, Nezworski TH. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

13. Egeland B, Jacobvitz D, Sroufe LA: Breaking the cycle of abuse. Child Development 59:1080-1088, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Belsky J: Etiology of child maltreatment: a developmental-ecological analysis. Psychological Bulletin 114:413-434, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Crittenden PM: Social networks quality of child rearing and child development. Child Development 56:1299-1313, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA, et al: Awareness of illness in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:113-132, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ghaemi SN, Pope HG: Lack of insight in psychotic and affective disorders: a review of empirical studies. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 2:22-33, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. McEvoy JP, Apperson LJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Insight in schizophrenia: relationship to psychopathology. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:44-47, 1989Google Scholar

19. McEvoy JP, Freter S, Everett G, et al: Insight and the clinical outcome of schizophrenic patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:48-51, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

21. Astrachan BM: Report of Mental Health Task Force Special Wallace Case Investigation Team, Chicago, May 20, 1994Google Scholar

22. Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D: Defining child maltreatment: the interface between policy and research, in Child Abuse, Child Development, and Social Policy. Edited by Cicchetti, D, Toth SL. Norwood, NJ, Ablex, 1993Google Scholar

23. David A: Insight and psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 156:798-808, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. David A, Os JV, Jones P, et al: Insight and psychotic illness: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. British Journal of Psychiatry 167:621-628, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Caldwell BM, Bradley RH: Home Observation for the Measurement of the Environment. Administration Manual, rev ed. Little Rock, University of Arkansas Press, 1984Google Scholar

26. Fink LA, Bernstein D, Handelsman L, et al: Initial validity and reliability of the childhood trauma interview: a new multidimensional measure of a childhood interpersonal trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1329-1335, 1995Link, Google Scholar

27. Abidin RR: Parenting Stress Index (short form). Charlottesville, Va, Pediatric Psychology Press, 1990Google Scholar

28. Barrera M: Social support in the adjustment of pregnant adolescents: assessment issues, in Social Networks and Social Supports. Edited by Gottlieb BH. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1981Google Scholar

29. George C, Solomon J: Representational models of relationship: links between caregiving and attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal 17:198-216, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Miller LJ, Jacobsen T, Jones V, et al: Parenting Assessment Team Training Manual. Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Psychiatry, 1998Google Scholar

31. Jacobsen T, Miller LJ, Kirkwood KP: Assessing parenting competency in individuals with severe mental illness: a comprehensive service. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:189-199, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Klein DN, Ouimette PC, Kelly HS, et al: Test-retest reliability of team consensus best-estimate diagnoses of axis I and II disorders in a family study. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1043-1047, 1994Link, Google Scholar

33. McEvoy JP, Appelbaum PS, Geller JL, et al: Why must some schizophrenic patients be involuntarily committed? The role of insight. Comprehensive Psychiatry 30:13-17, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA, et al: The assessment of insight in psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:873-879, 1993Link, Google Scholar

35. Lysaker P, Bell M, Milstein R, et al: Insight and psychological treatment compliance in schizophrenia. Psychiatry 57:307-315, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Soskis DA, Bowers MB: The schizophrenic experience. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases 149:443-449, 1969Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Nicholson J, Sweeney EM, Geller JL: Mothers with mental illness: I. the competing demands of parenting and living with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:635- 642, 1998Link, Google Scholar

38. Amador XA, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, et al: Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:826-836, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Michalakeas A, Skoutas C, Charalambous A, et al: Insight in schizophrenia and mood disorders and its relation to psychopathology. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 90:46- 49, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Cicchetti D, Toth SL: A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:541-565, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar