An Examination of Racial Differences Among Mentally Ill Offenders in Massachusetts

Abstract

Data from 169 mentally ill prison inmates who completed a three-month program to help them reenter the community were analyzed to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of white, black, and Hispanic participants. A total of 107 were Caucasian, 35 were black, and 27 were Hispanic. Caucasian participants were more likely to have affective disorders and to report a history of substance use problems. Black and Hispanic participants were more likely to have thought disorders. Black participants released from prison tended to migrate to more urban areas than Caucasians. Of those engaged in the community at program completion, 60 percent were Caucasian, 22 percent were black, and 18 percent were Hispanic.

Nearly 15 percent of persons in correctional custody are mentally ill, whereas mentally ill persons constitute only 5 percent of the general population (1). Black people are also overrepresented in correctional populations (2). They constitute approximately 12 percent of the U.S. population but account for 30 percent of all federal inmates and 50 percent of all persons in correctional custody; blacks are seven times more likely to be incarcerated than Caucasians (3).

Blacks have been reported to have significantly higher rates of schizophrenia and other affective disorders over the life course than Caucasians. However, when the analyses controlled for age, gender, marital status, and socioeconomic status, the difference in rates was no longer significant (4). More recent research has shown no significant differences in the rates of mental illness among blacks and Caucasians and that blacks have significantly lower rates of affective and substance use disorders than Caucasians (6).

Identifying and coping with mental illness is quite different in correctional settings than in the community. For instance, the stress of incarceration may be experienced differently by members of different racial and ethnic groups, and the rates of mental illness reported for some groups in prison may therefore be inflated. It is also possible that mental illness in persons from some minority groups is not identified and treated in prison because they do not seek help or because of cultural differences or distance from correctional staff (7). Nevertheless, as is the case for all incarcerated persons, mentally ill offenders are expected to reside in the community after release from prison. A better understanding of their distinct configuration of needs can help ensure the provision of appropriate services.

Methods

To enhance the community reintegration of mentally ill offenders completing prison sentences, the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health established the forensic transition team program in 1998. This program provides services to offenders who are identified as mentally ill either before or after entering prison. The team staff work with the inmates before their release to assess their needs and monitor the release transition process for up to three months after release (7).

Data for this study were collected and coded from the transition program forms. Data on all 169 clients who completed the transition process in the first two years of the program's operation were analyzed to determine whether any variables differed by race, including short-term community outcomes.

The Department of Correction and the Department of Mental Health in Massachusetts report separate data for Caucasian, black, and Hispanic groups and combine data for Native Americans and Asians because of the small numbers (8). We have adopted the same format; however, the term Hispanic is used cautiously because it is imprecise. Subsumed under the term Hispanic were people who identified themselves as Latino, Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and Dominican, among others. Furthermore, the reliability of self-reports of being Hispanic varies with the situation and instrumentation, which may lead to underestimating or overestimating the number of Hispanics in a population.

Results

Statewide correctional data and data from the Department of Mental Health Services on persons receiving services in the community indicated that the proportion of black offenders in correctional custody who were identified as mentally ill (35 persons, or 21 percent) was smaller than the proportion of blacks in the prison population (2,813 persons, or 30 percent) and larger than the proportion of blacks receiving mental health services in the community (896 persons, or 8 percent).

Of the 169 mentally ill offenders released from correctional custody who completed the forensic transition program, 107 (63 percent) were Caucasian, 35 (21 percent) were black, and 27 (16 percent) were Hispanic. Of the 131 men, 81 (62 percent) were Caucasian, 30 (23 percent) were black, and 20 (15 percent) were Hispanic. Thirty-eight of the 169 program participants (22 percent) were women. Among the women, 25 (67 percent) were Caucasian, five (14 percent) were black, and seven (19 percent) were Hispanic.

Sixty-six of the program participants (39 percent) reported a history of homelessness—39 Caucasians (59 percent), 14 blacks (21 percent), and 13 Hispanics (20 percent). The difference between groups was not statistically significant. On release to the community, 14 of the 35 black mentally ill offenders (40 percent) returned to the Boston area, compared with 16 of the 67 Caucasian offenders (24 percent) (χ2=40.96, df=9, p<.01).

Diagnostic differences were found between the offenders from minority groups and Caucasian offenders. Although these differences were not statistically significant, they suggest diagnostic trends. Affective disorders such as depression were more common among the Caucasian offenders. Forty-eight Caucasians (45 percent) had affective disorders, compared with 13 blacks (37 percent) and 12 Hispanics (44 percent). Nearly 60 percent of both the Hispanic offenders (N=14) and the black offenders (N=20) were diagnosed as having thought disorders such as schizophrenia, compared with 46 Caucasians (43 percent).

A total of 117 program participants (69 percent) had a history of substance use problems. Seventy-six Caucasians (71 percent) reported substance use problems, compared with 21 blacks (60 percent) and 20 Hispanics (74 percent). The differences between groups were not significant. However, the large proportion of participants with substance use problems is worthy of note.

A total of 109 participants (65 percent) had previously received services from the Department of Mental Health. Seventy Caucasians (65 percent) and 25 blacks (71 percent) had received these services, compared with 14 Hispanics (52 percent). The differences were not statistically significant.

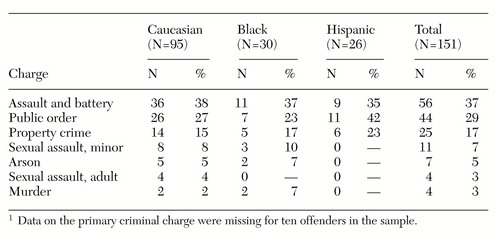

Table 1 presents data on the most recent offense for the three groups. The rates of person-related violent offenses and sexual assaults were higher among Caucasian offenders. The most common charge among Hispanics was a public-order offense—disorderly conduct, breach of peace, drug possession, or prostitution. Among all the mentally ill offenders in the sample, assault and battery was the most common offense. Of the 21 participants having to register as sex offenders on release, 17 (81 percent) were Caucasian.

Outcome measures for the 169 program participants indicated that 104 (62 percent) made a successful community engagement, 17 (10 percent) were lost to follow-up, 34 (20 percent) were immediately hospitalized after release from prison, eight (5 percent) were rehospitalized within three months after release, and six (3 percent) were sent back to prison within three months after release.

Of those engaged in the community at program completion, 62 (60 percent) were Caucasian, 23 (22 percent) were black, and 19 (18 percent) were Hispanic. These differences were not significant. None of the 35 black program participants were lost to follow-up or reincarcerated. Although the differences were not statistically significant, blacks were disproportionately represented both among those who were immediately hospitalized after release (ten blacks, or 31 percent) and those who were hospitalized within three months (three blacks, or 36 percent).

Discussion

Although the sample size limited the ability to detect statistically significant differences, this initial study of mentally ill offenders in Massachusetts found some variations among racial and ethnic groups that have implications for service delivery in correctional settings and the community. For example, black offenders released from prison tended to migrate to more urban areas than Caucasian offenders. Service agencies in urban areas should ensure that staff are trained to understand both the reintegration needs and the cultural needs that might affect clinical care among mentally ill offenders returning to the community.

The black mentally ill offenders in this study also had longer histories of receiving community mental health services than the Hispanic offenders, suggesting that outreach strategies need to be implemented to overcome potential language and cultural barriers to access (9). In addition, all mentally ill offenders might benefit from treatment for dual diagnosis of a substance use disorder and a mental disorder. Studies of the general population have not found higher rates of substance abuse among blacks or Hispanics. However, the chronic stress associated with poverty accounts for elevated rates of substance use problems among mentally ill persons; such problems diminish the likelihood of retention in community treatment (10).

Although the differences were not statistically significant, a trend was noted for black and Hispanic mentally ill offenders to be more likely to be diagnosed with a thought disorder. In addition, Caucasian mentally ill offenders were more likely to commit more violent crimes, such as sex offenses. Given that little diagnostic variation between the races has been found in community-based studies, the elevated percentages of particular disorders among mentally ill offenders by race or ethnic group is worthy of further attention (2,3). A closer examination of violent mentally ill offenders is also warranted, especially because of the higher rates of hospitalization among blacks released from prison. Their hospitalization suggests that they are considered a risk to themselves or others while living in the community.

Conclusions

People of color are overrepresented in the correctional system, yet the offender population identified as mentally ill is disproportionately Caucasian. Some effort should be made to explore whether mental illness in persons from minority groups is underidentified in prison and whether the referral process for mental health services is culturally biased (7). Although it is unlikely that correctional staff members will always be able to discern which inmates need mental health assessment, the stigma associated with receiving mental health services, language barriers, or cultural distance between service providers and inmates may inhibit blacks, Hispanics, and other people of color from seeking services, in correctional settings as well as after release to the community.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Karin Orr, L.I.C.S.W., Xiaogang Deng, Ph.D., and Nancy Lopez, Ph.D., for their thoughtful contributions.

Dr. Hartwell is affiliated with the department of sociology at the University of Massachusetts Boston, 100 Morrissey Boulevard, Boston, Massachusetts 02125-3393 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Charges of 99 mentally ill offenders in a community transition program, by racial or ethnic group1

1 Data on the primary criminal charge were missing for ten offenders in the sample

1. Lamb HR, Weinberger L, Gross B: Community treatment of severely mentally ill offenders under the jurisdiction of the criminal justice system: a review. Psychiatric Services 50:907-913, 1999Link, Google Scholar

2. Tonry M: Malign Neglect: Race, Crime, and Punishment in America. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

3. Beck AJ, Gillard DK (eds): Prisoners in 1994. Washington, DC, Bulletin of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1995Google Scholar

4. Robins LN, Regier DA (eds): Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhoa S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hall LE, Tucker CM: Relationships between ethnicity, conceptions of mental illness, and attitudes associated with seeking psychological help. Psychological Reports 57:907-916, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hartwell SW, Orr K: Models of care: Massachusetts' forensic transition program. Psychiatric Services 50:1220-1222, 1999Link, Google Scholar

8. Ragaas RV: A statistical description of the sentenced population of Massachusetts correctional institutions on January 1, 1996. Boston, Massachusetts Department of Correction, 1997Google Scholar

9. Kopelowicz A: Social skills training: the moderating influence of culture in the treatment of Latinos with schizophrenia. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 19:101-108, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Westermeyer J: Ethnic and cultural factors in dual disorders, in Double Jeopardy: Chronic Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders. Edited by Lehman AF, Dixon LB. Langhorne, Pa, Gordon and Breach, 1995Google Scholar