Managed Care and Children's BehavioralHealth Services in Massachusetts

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors investigated changes in treatment patterns and costs of care for children after the implementation of the Massachusetts Medicaid carve-out managed care plan. METHODS: The authors hypothesized that after the introduction of managed care, per-child expenditures would be reduced, continuity of care would not improve, and per-child mental health expenditures would undergo larger reductions for disabled children, compared with children enrolled in the Aid to Families With Dependent Children program. Using data from Medicaid and the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, the authors studied 16,664 Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries aged one to 17 years for whom reimbursement claims were submitted for psychiatric or substance use disorder treatment at least once during the two years before the introduction of managed care (1991 to 1992) or during the two years afterward (1994 to 1995). Multivariate analysis was used to estimate changes in probability of admission, and, among patients admitted, to identify factors accounting for variation in length of stay. To assess the variation in expenditures, we regressed the same variables, using the natural logarithm function to transform total mental health expenditures data and inpatient expenditures data to reduce skewness. RESULTS: After the introduction of managed care, per-child expenditures were lower, especially for disabled children, and the Department of Mental Health was used as a safety net for the most seriously ill children without increasing state expenditures. Continuity of care appeared to decline for disabled children. CONCLUSIONS: It is likely that a combination of factors related to the reported changes in patterns of care and expenditures were responsible for the overall per-child expenditures.

Managed care has drawn criticism from consumers unhappy with being restricted to network providers or worried about denial of access to medically necessary treatment. In addition, critics fear that financial pressures on clinicians might result in reductions in the quality of care delivered. Nevertheless, two-thirds of state legislatures have moved to place Medicaid members, including children, into managed care plans.

The dramatic shift from traditional fee-for-service systems to managed care by state Medicaid agencies took place even though little evidence was available indicating that managed care is more efficient or effective. Studies of children's services are particularly scarce, perhaps because children's mental health needs are so complex (1,2,3,4,5,6). One of the few reports of children in managed care comes from Burns and colleagues (7), who studied children in a pilot managed care plan and found that capitation among local mental health providers led to reductions in hospital admissions, increased use of hospital alternatives, and lower costs per child served, compared with the state's fee-for-service Medicaid plan.

Our study included 16,664 child Medicaid enrollees in Massachusetts during the two-year periods of 1991 to 1992, before the introduction of managed care, and 1994 to 1995, after the introduction of managed care. We hypothesized that after the introduction of managed care, per-child expenditures would be reduced, continuity of care would not improve, and reductions in per-child expenditures would be larger for children with disabilities than for children enrolled in the Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC) program who were treated for mental illness.

In 1992 Massachusetts was the first state to receive a 1915b waiver from the Health Care Financing Administration requiring all Medicaid beneficiaries to enroll in a local health maintenance organization or to select a Medicaid-approved primary care clinician. About two-thirds of the enrollees in the AFDC program and virtually all psychiatrically disabled beneficiaries chose the latter. Under the primary care clinician plan, Medicaid chose a proprietary vendor to manage all Medicaid-reimbursed mental health benefits. The contract terms required the vendor to make available all behavioral health services, including acute inpatient and outpatient treatment, crisis stabilization, psychiatric day treatment, residential detoxification, and methadone treatment. The vendor added diversionary services, including acute residential treatment programs, family stabilization, and partial hospitalization programs.

The managed care vendor pursued four specific cost-containment strategies: negotiation of lower reimbursement rates with a network of providers; implementation of an aggressive utilization management plan; development of community-based alternatives to hospitalization; and development of a statewide network of general and private psychiatric hospitals.

The vendor was paid a risk-adjusted premium for disabled beneficiaries almost four times that for nondisabled children. The vendor paid providers on a fee-for-service basis. The contract with the managed care company stated that its financial risk would be limited to $1 million in profit or loss, defined as the risk corridor. In subsequent years Medicaid and the vendor agreed to some adjustments in the premium and in the risk corridor.

Safety-net services provided by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health were not included in the contract. These services, which included residential treatment and hospitalization in state facilities, were used by only a very small proportion of all children who had serious emotional disorders. Children whose clinical needs could not be met by the managed care vendor were served by the Department of Mental Health. The contract made explicit the usually implicit division between acute Medicaid-reimbursed treatment and long-term care provided historically by the state mental health agency.

In this study we evaluated the Medicaid behavioral health carve-out plan. We hypothesized that hospitalization would be reduced as a result of aggressive utilization management but that continuity of care would not improve. Our hypothesis was based on our understanding of how carve-out plans operate—they separate administration and financial control from clinical activities and thus may not be as successful in establishing continuity of care.

We also hypothesized that the percentage decrease in mental health expenditures would be larger for disabled children than for children enrolled in AFDC. Earlier studies (8) of adult AFDC enrollees with lower per-person treatment expenditures than disabled beneficiaries before the introduction of managed care, had a smaller percentage reduction in their expenditures after managed care was introduced. The authors thought that because AFDC enrollees had a much lower rate of hospitalization for mental illness than did disabled beneficiaries, the requirement for prior approval was a less effective strategy for reducing their expenditures. Compared with AFDC enrollees, disabled beneficiaries had a higher rate of inpatient admission and longer inpatient stays before the introduction of managed care, which presented a greater opportunity for managed care strategies to improve efficiency.

Methods

This was an observational study using administrative data to compare the patterns of service use and related expenditures of children who were Medicaid beneficiaries during the two years before the introduction of managed care and two years after its introduction.

The primary source of data for the study was paid claims from the Department of Medical Assistance (Medicaid) in the 1991-1992 period and in the 1994-1995 period. Because seriously emotionally disturbed children sometimes are treated in state hospitals that are not reimbursed by Medicaid or the managed care company, we merged state hospital admissions data from Department of Mental Health inpatient files with the Medicaid paid claims. Use of the department's data provides a more complete picture of treatment patterns during the study years. Details of the methods used to create the database have been reported elsewhere (9).

Sample

We studied 16,664 Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries aged one to 17 years for whom at least one reimbursement claim was submitted for psychiatric or substance use disorder treatment during the two study periods. These claims for reimbursement came from 100 percent of the disabled Medicaid-enrolled children treated for a mental illness (N=8,793) and a random sample of 10 percent of AFDC Medicaid-enrolled children treated for a mental illness (N= 7,871). Overall, the number of children treated increased by 36 percent, from 7,047 to 9,617, during the managed care study period. The new enrollees were primarily disabled children, reflecting active efforts to enroll eligible children who did not have health insurance coverage.

The sample was predominantly white and under the age of 12. Disabled children were likely to have serious emotional disorders but also may have been eligible because of a physical disability and treated for a mental illness that was less serious. The AFDC category included children whose parents were receiving income support from the state and who received health benefits through Medicaid. Most of these children were being treated for less serious mental illness.

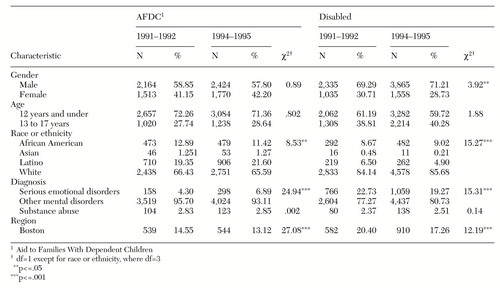

Overall, the demographic characteristics remained relatively stable during the study period despite the large increase in the number of children treated. However, the proportion of children treated in the Boston region dropped from 18 percent to 13 percent of the total after managed care was introduced. Because of the large sample size, differences in many of the sociodemographic characteristics listed in Table 1 were statistically significant.

We examined diagnoses, by aid category, for upward diagnostic creep—that is, the tendency of clinicians to use a more serious diagnosis to ensure that payment for services provided is not denied in the managed care utilization review process. Changes in the severity of mental illness before and after the introduction of managed care would make comparisons questionable, but overall, the proportion of children treated for psychoses or substance use disorders did not change.

Analyses

Access. We measured access to care by examining the number of unduplicated beneficiaries treated—that is, beneficiaries for whom there was at least one paid mental health care claim—and the proportion of those treated who were hospitalized, by each aid category.

Patterns of care. We examined treatment patterns, including hospitalizations and length of stay for children. To study continuity of care, a key component of the quality of care delivered, we examined patterns of posthospitalization readmissions and outpatient aftercare. We assigned each discharge to one of four mutually exclusive categories: no follow-up outpatient contact and no rehospitalization within 30 days; follow-up contact within 30 days and no readmission; no follow-up contact within 30 days and at least one rehospitalization; and both follow-up contact and readmission within 30 days.

Assessment of expenditures. We derived costs for Medicaid services from the paid claims indicating the amount reimbursed. We included all claims for any reimbursed mental health treatment, including those for special programs developed by the vendor. We also included the costs of state hospital care, derived from hospital-specific per diem rates paid by the Department of Mental Health, as a way of detecting cost shifting to this agency (9). Total expenditures were determined by aggregating Department of Mental Health state hospital and Medicaid-reimbursed inpatient and outpatient mental health expenditures for each beneficiary. All expenditure figures are reported in 1995 dollars by adjusting expenditures in earlier years for inflation using the gross domestic product deflator (10). We transformed expenditures data using the natural logarithm function to reduce skewness.

Multivariate analyses. We used logistic regression analysis to estimate the probability of admission, before and after the introduction of managed care, for children in both aid categories and, among those admitted, we estimated variation in length of stay. We also used this model to estimate total mental health expenditures. The model used included a vector of sociodemographic and clinical variables, a dummy variable for living in the Boston area, which has a much higher per capita bed ratio than the rest of the state, and a dummy variable for managed care. All analyses performed were carried out separately for each aid category, eliminating the need to weight the samples.

Results

Access

The number of children receiving any reimbursed mental health treatment increased substantially after the introduction of managed care. The number of disabled children receiving treatment increased the most, by 66 percent, in the managed care study period. Access to hospitals by all children decreased about 40 percent after managed care was initiated.

Patterns of care

Among AFDC children receiving Medicaid benefits, both the number of hospital admissions and, for those admitted, the length of stay were reduced. Young children were much less likely to be admitted, and children with serious mental illness were more likely to be admitted.

Among the disabled children a somewhat different pattern emerged. The per-child rate of admission dropped almost by half, but this change was coupled with an increased average length of stay for those who were admitted and more admissions per child admitted. These findings are consistent with the policy of limiting hospitalization to the most severely ill. The increase in length of stay occurred in Department of Mental Health state facilities, not in acute care general hospitals. Average length of stay was reduced in general hospitals after managed care was introduced (from 38 days to 17 days), and increased in Department of Mental Health hospital beds in the same period (from 88 days to 100 days).

Continuity of care, measured as readmissions and outpatient follow-up for AFDC children discharged from inpatient units, stayed about the same or improved slightly after managed care was in place. The number of readmissions rose slightly, and almost all readmissions were preceded by some form of outpatient treatment, suggesting that lack of follow-up may not have been the cause of the readmission.

Our data suggest that continuity of care for disabled children deteriorated. Follow-up treatment decreased, and the number of readmissions without follow-up increased. However, caution must be exercised in interpretation of these data. They may misrepresent actual levels of posthospitalization treatment because of the emergence of new, self-contained intensive residential treatment programs. These programs are a comprehensive alternative to hospitalization and include physician visits and other on-site mental health services paid for by the Department of Mental Health and not billed to Medicaid. However, child-specific data are not available from the department to identify outpatient visits to physicians in such programs.

Assessment of expenditures

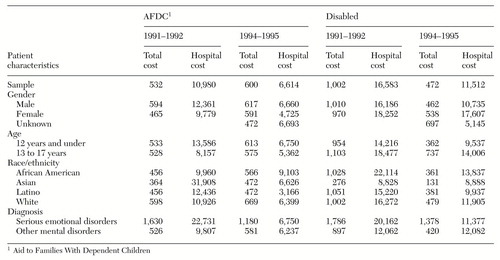

We found that per-child annual median mental health expenditures decreased substantially during the managed care study period for the disabled group, from $1,002 to $472. During the same time period, median annual per-child expenditures rose slightly for the AFDC group, from $532 to $600. We also found that the median cost of a hospitalization episode for both groups of children was lower after managed care was in place (see Table 2). This reduction was due in part to reduced lengths of stay but also to negotiated (lower) per diem payments for in-network hospitals.

Critics often ask whether, under managed care, ambulatory treatment is substituting for inpatient care. In this study we found that the total median expenditure per AFDC child increased slightly while the number of hospital admissions dropped, which might be considered evidence of a substitution effect. We did not find a similar pattern for disabled children.

Multivariate analyses

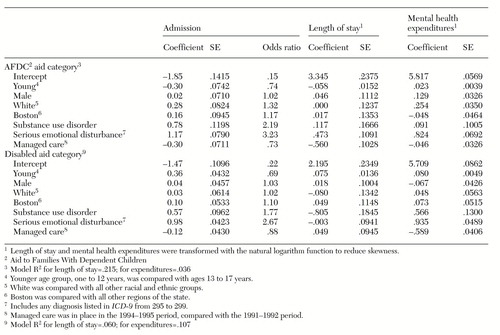

When the children's personal and clinical characteristics were taken into account, managed care was associated with a reduced probability of inpatient admission regardless of aid category. Seriousness of condition, as indicated by a diagnosis of a substance use disorder or a serious emotional disorder, and younger age also were associated with significantly higher odds of being admitted. Models estimating inpatient length of stay and total mental health expenditures varied by aid category. For AFDC children, the advent of managed care was associated with a lower average length of stay, but not with lower overall expenditures. For disabled children, the reverse was true: the advent of managed care was associated with higher overall expenditures, but not with an increased average length of stay (see Table 3).

Discussion

We found that Medicaid children had fewer hospitalizations and lower annual mental health expenditures after the introduction of managed care. Especially encouraging is that use of outpatient treatment by AFDC children increased under managed care, and inpatient admissions dropped. The large reduction in hospital admissions was the primary reason for reduced expenditures, especially among disabled children. These findings are consistent with the policy goals of the Division of Medical Assistance (Medicaid) and the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, namely, to provide treatment in the least restrictive setting and to provide acute care efficiently. In addition, these findings suggest that the Department of Mental Health remained the safety net provider for disabled and disturbed children. The department has always been the provider of last resort, and this role appears to have been maintained. Although only a small number of children had state hospital admissions, these hospitalizations were lengthy and expensive.

Using observational data to test hypotheses about managed care has many limitations. In this study we know that the number of children treated increased dramatically, but we could not determine whether increased access led to bias in the direction of children whose needs were lower, rather than higher. When enrollment increases and per-person costs decrease, it is difficult to determine whether cost-shifting from Medicaid to the state mental health agency—the Department of Mental Health—took place, because we cannot be certain that new enrollees had the same mental status and need for treatment as those enrolled before managed care. However, because we included state hospital data, we can report that managed care was associated with the same or lower total per-person mental health expenditures when both acute Medicaid-reimbursed treatment and long-term care funded by the Department of Mental Health were included (10).

An important finding that was secondary to the main purpose of the study was that the most seriously ill children were more likely to be admitted to hospitals, and when admitted, they stayed longer than before the advent of managed care. Critics of managed care often claim that utilization review and precertification procedures are capricious. Although we cannot be sure which hospital admissions were appropriate or how many children denied admission should have been admitted, our findings suggest that review efforts reflect clinical judgment and are not a random process.

The study of mental health service patterns of care for children is complicated, because inpatient admission and discharge decisions rest on many factors. Future studies need to take into account factors related to appropriate discharge: Can the child be discharged home? Is this a foster child lacking placement or a victim of abuse and neglect who needs out-of-home placement? Are there legal problems related to the child or the parents? What about the discharge that requires integrated planning with the child's school or the department of welfare? Each of these considerations may add days or weeks to a hospital stay. In a managed care environment, payment for these added days may not be forthcoming, leaving hospitals in the position of providing unreimbursed care until the hospital discharge takes place, however long that may be. If a state agency responsible for the welfare of children were asked to foot the bill for these administrative days, the burden would be lifted from hospitals and placed directly on those who must coordinate and oversee nonmedical aspects of placement.

Future studies should also examine physically disabled children enrolled in Medicaid who are treated for mental disorders. In this group, mental health treatment might be complicated and lengthy even if the mental disorder is typically considered less serious. In addition, the presence of substance use problems may greatly increase the treatment complexity and the length of stay. Finally, continuity of care should be explored in greater depth. Some form of data collection needs to be considered that will capture the services provided by mental health professionals in residential settings. The scope of future studies should be expanded to include data from the medical sector, social services, and the educational system that might be affected by the reduced access to inpatient care.

Conclusions

To wait for the ideal evaluation of the changes taking place in our health systems today is pointless. And to think that we can put the health care system in a laboratory and carry out the equivalent of a randomized clinical trial is to be blind to the role of choice and predisposition on the part of both patients and clinicians. Nevertheless, policy makers must respond to the political and economic pressures of the marketplace. We can only hope that some descriptive information about one small segment of the managed care population will be better than no information at all to those who must make decisions every day about how best to provide health care, especially to those for whom we hold the government responsible.

In this report, we have described changes that took place in one managed care plan for children. The plan appears to have met its key goals: it increased access to care, especially outpatient treatment; it was more efficient in providing acute care; it used the state Department of Mental Health as a safety net for the most seriously ill children; and it provided utilization review selectively. Equivocal findings about the continuity of care raise questions about the quality of care that we cannot answer. However, without information about the quality of care and outcomes, our findings of positive changes represent only an initial, exploratory step.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute of Mental Health grant R01-MH-46522. The Massachusetts Department of Medical Assistance and the Department of Mental Health assisted in providing data and technical support.

Dr. Dickey and Mr. Azeni are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of Harvard Medical School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Dr. Normand is with the department of health care policy of Harvard Medical School and the department of biostatistics of the Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Norton is affiliated with the department of health policy and administration in the School of Public Health of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Dr. Rupp is program officer for financing and managed care research in the services research and clinical epidemiology branch of the National Institute for Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland. Send correspondence to Dr. Dickey, Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Hospital, 1493 Cambridge Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of 16,664 Massachusetts children receiving Medicaid benefits, by aid category

|

Table 2. Median costs (in dollar) for 16,664 Massachusetts children receiving Medicaid benefits

|

Table 3. Multivariate models of the probability of admission and factors affecting length of stay and total mental health expenditures for 16,664 Massachusetts children receiving Medicaid benefits

1. Bickman L, Guthrie PR, Foster EM, et al: Evaluating Managed Mental Health Services: The Fort Bragg Experiment. New York, Plenum, 1995Google Scholar

2. Stroul BA, Friedman RM: A System of Care for Children and Youth With Severe Emotional Disturbances. Washington, DC, Georgetown University Child Development Center, National Technical Assistance Center, 1986Google Scholar

3. Knitzer J: Unclaimed Children. Washington DC, Children's Defense Fund, 1982Google Scholar

4. Adolescent Health, vol 2, Background and Effectiveness of Selected Prevention and Treatment Services. Pub OTA-H-466. Washington, DC, US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, 1991Google Scholar

5. Inouye S: Children's mental health issues. American Psychologist 43:813-816, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hoagwood K, Rupp A: Mental health service needs, use, and costs for children and adolescents with mental disorders and their families: preliminary evidence, in Mental Health, United States, 1994. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MS. DHHS pub (SMA)94-3000. Washington, DC, Department of Human Health and Services, 1994Google Scholar

7. Burns B, Teagle SE, Schwartz M, et al: Managed behavioral health care: a Medicaid carve-out for youth. Health Affairs 18:214-225, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Norton EC, Lindrooth RC, Dickey B: Cost-shifting in a mental health carve-out for the AFDC population. Health Care Financing Review 18:95(108, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

9. Dickey B, Normand SL, Norton EC, et al: Managing the care of schizophrenia: lessons from a four-year Massachusetts Medicaid study. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:945-952, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Norton EC, Lindrooth RC, Dickey B: Cost-shifting in managed care. Mental Health Services Research 1:185-196, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Survey of Current Business. Washington, DC, US Department of Commerce, 1995Google Scholar