Psychopharmacology: Insight and Comorbid SubstanceMisuse and Medication ComplianceAmong Patients With Schizophrenia

Although antipsychotic medications are effective in acute treatment and relapse prevention among patients with schizophrenia, compliance remains low (1). Both subjective response to medication and attitudes toward treatment are recognized to influence compliance (2,3). However, results of studies examining the effects on compliance of patients' insight about their illness are inconsistent (4,5). Furthermore, comorbid substance misuse, which is common among patients with schizophrenia, is also associated with noncompliance (6).

We examined levels of noncompliance with oral antipsychotic medication regimens and the factors that influenced it among a group of patients consecutively readmitted to a hospital with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. We hypothesized that comorbid substance misuse may explain why some patients with insight do not adhere to their medication regimen. In addition, we assessed the potential impact that noncompliance may have on psychopathology and duration of hospital admission.

Methods

After the study was approved by a committee on ethics, all patients residing within a geographically defined urban population of 165,000 who were readmitted with psychotic illness to a hospital over a 12-month period (July 1, 1996, to August 1, 1997) were asked to take part in the study.

We evaluated symptoms using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (7). Before the study began, we obtained intraclass correlation coefficients in excess of .84 for all subscales and the total score of the PANSS. Age at onset of psychotic symptoms was ascertained by an interview using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (8) and examination of case notes.

We used Birchwood's self-report questionnaire to measure insight (9). We evaluated subjective response to neuroleptics and attitude toward medication using the Drug Attitude Inventory (2).

We assessed compliance using a structured clinical interview (10) that rates a patient's medication compliance in the month before admission. Patients are rated on a 4-point scale, with 1 indicating a compliance of 0 percent to 24 percent; 2, 25 percent to 49 percent; 3, 50 percent to 74 percent; and 4, 75 percent to 100 percent. Any individual who scored 3 or less was classified as having irregular compliance; those who scored 4 were classified as having regular compliance. This classification is consistent with those of previous studies of compliance (6). Information from the interview with the patient was supplemented with collateral information from family members and mental health professionals. When reported levels of compliance differed, we used the lowest reported level of compliance.

We used the SCID to establish each patient's diagnosis and to ascertain the presence of current comorbid substance abuse or dependence. Information from the SCID was augmented with information from family and health professionals who were in close contact with the patient.

Data were analyzed with SPSS software. Between-group differences were analyzed with two-tailed independent tests for continuous variables and chi square analysis for categorical variables. We performed logistic regression analysis to determine which variables were associated with compliance with oral neuroleptic regimens.

Some factors may play an important role in influencing compliance with depot medication regimens but not with oral medication regimens. For example, compliance with depot neuroleptic regimens is affected by factors determining depot clinic attendance (6), such as patients' geographical location and the availability of transportation, as well as by the quality of the therapeutic relationship between the patient and the mental health professional administering the depot medication. In addition, patients started on depot medication rather than oral medication may constitute a distinct patient group. Therefore, we limited investigation of the clinical correlates of noncompliance to patients taking only oral medication.

Results

Over the 12-month study period, 121 patients with psychotic disorders were readmitted to a hospital. Six patients declined to take part in the study, and two were unable to complete the assessment because of a learning disability. Of the remaining 113 patients, 102 met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Of the 102 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 15 were admitted electively. Because we were interested in the relationship between compliance and psychotic relapse, these patients were not included in further analyses.

The final sample included 87 patients with acute psychotic relapse of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder readmitted to a hospital over the 12-month study period. The 21 patients who were taking depot medication were significantly more likely than the 66 patients taking only oral medication to be regularly compliant; 12 of the 21 patients (57 percent) were compliant versus 22 of the 66 patients (33 percent; likelihood ratio χ2=3.79, df=1, p=.051).

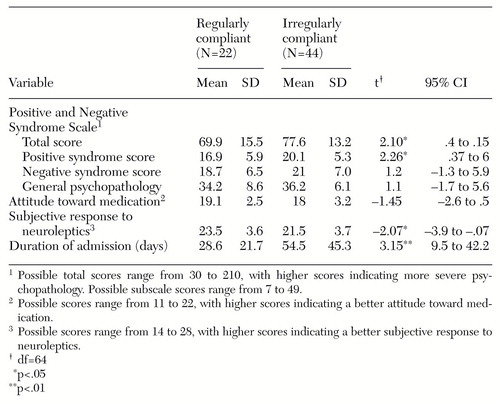

Of the 66 patients taking oral medication, 41 were male and 25 were female. Their mean±SD age was 37.3± 12.6 years, and the mean±SD duration of illness was 13.7±12.8 years. Only 22 patients (33 percent) reported regular compliance during the month before admission. The remaining 44 patients (67 percent) were irregularly compliant. The regularly and irregularly compliant groups did not differ in age, gender, duration of illness, or age at onset of psychotic symptoms. Table 1 summarizes the clinical comparison between regularly and irregularly compliant groups taking oral medication.

Fifteen of the 66 patients (23 percent) met DSM-IV criteria for current comorbid substance abuse or dependence. Fourteen of these patients (93 percent) were irregularly compliant. Patients with comorbid substance misuse were significantly more likely to be irregularly compliant—14 of 44 irregularly compliant patients (32 percent) versus one of 22 regularly compliant patients (5 percent; likelihood ratio χ2=6.2, df=2, p=.01).

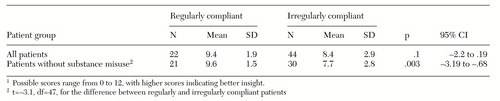

No significant difference was found between regularly and irregularly compliant patients in the total insight score. However, when the analysis excluded patients with current comorbid substance misuse, the 21 regularly compliant patients had a significantly higher mean insight score than the 30 who were irregularly compliant (Table 2).

We used a logistic regression model with regular and irregular compliance as the dependent variable and gender, age, age at onset of illness, insight, subjective response to neuroleptics, attitudes toward treatment, and comorbid substance misuse as independent variables. The overall model was significant (χ2=11.95, df=2, p=.003). Two variables differentiated between the two groups—current comorbid substance misuse (Wald statistic=5.72, df=l, p<.02) and insight into illness (Wald statistic=3.8, df=1, p<.05).

Discussion

The study was limited by reliance on self-reported measures of compliance, particularly because patients tend to overestimate compliance with neuroleptics. However, the use of quantitative measures also has drawbacks, including inaccuracy and a failure to give further insight into the reasons behind noncompliance (3). We attempted to minimize this difficulty by asking family members and health professionals who were in close contact with the patients to rate their level of compliance in the month before admission.

We believe that 67 percent is a conservative estimate of noncompliance with oral neuroleptics among patients with schizophrenia recently readmitted to the hospital. Because there is considerable evidence that with each relapse, patients experience a deterioration in both social and occupational functioning, our finding highlights the importance of identifying those who are at risk of noncompliance. It also suggests the need for specific intervention strategies to promote compliance.

In this study, patients taking depot medication were more likely to be compliant than those taking oral medication. However, longitudinal studies have demonstrated that switching patients to depot medication has limited or only short-term benefit in terms of compliance (11); patients switched to depot medication were significantly more compliant in the month after discharge from the hospital, but this benefit was lost at six- and 12-month follow-up.

We found no differences between regularly compliant and irregularly compliant groups in gender, age, age at onset of illness, duration of illness, or prescribed dosage of oral medication. Previous studies have been contradictory in this regard. No single demographic or clinical variable has been consistently associated with noncompliance (1), and therefore these variables have been reported to be poor predictors of noncompliance. However, the irregularly compliant patients in our study manifested more positive symptoms on admission and required hospital stays approximately twice as long as those of the compliant patients. The economic implications are obvious; however, the distress that relapse and hospitalization cause patients and their families is less tangible.

We found that comorbid substance misuse was significantly associated with poor compliance with neuroleptic regimens. Given the negative impact that both noncompliance (12) and substance misuse (6) can have on outcomes of patients with schizophrenia, some investigators have emphasized the use of dual diagnosis relapse prevention strategies to manage these patients (13). Furthermore, irregularly compliant patients reported more negative subjective or dysphoric response to neuroleptics than those who were regularly compliant. Some investigators perceive patients' description of their subjective feelings to neuroleptics as unreliable (14); however, others have demonstrated an association with the presence of extrapyramidal side effects (15).

Studies examining the relationship between insight and compliance have been inconsistent. Although we found no association between the level of insight and compliance in the group as a whole, when patients with comorbid substance misuse were excluded from the analysis, we did find insight to be related to compliance. Insight may influence compliance among patients with schizophrenia, but comorbid substance misuse may prevent patients from complying with neuroleptics, whatever their level of insight. Furthermore, when comorbid substance misuse and other confounding variables were controlled for, level of insight was a significant factor in determining whether a patient was regularly compliant. These findings illustrate the complex nature of the relationship between insight and compliance with neuroleptic medication regimens.

Conclusions

Noncompliance is common among patients with schizophrenia and has a negative impact on the course of the illness. Comorbid substance misuse, negative subjective response to neuroleptics, and lack of insight are some of the factors that contribute to noncompliance. Better understanding of these and other risk factors and further research into specific intervention strategies aimed at improving medication compliance are warranted.

Acknowledgment

This study was made possible by funding from the Stanley Research Foundation.

The authors are affiliated with the Theodore and Vada Stanley research unit at the Cluain Mhuire family service of St. John of God adult psychiatric services, Newtownpark Avenue, Blackrock, County Dublin, Ireland. Send correspondence to Dr. O'Callaghan (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Clinical comparison between regularly and irregularly complaint patients taking oral neuroleptics

|

Table 2. Insight into illness among 66 regularly and irregularly compliant patients taking oral neuroleptics and among a subset of 51 patients without current comorbid substance misuse1

1. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK: Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:637-651, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood MR: A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychological Medicine 13:177-183, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Weiden P, Rapkin B, Mott T, et al: Rating of Medication Influences (ROMI) scale in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:297-310, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. MacPherson R, Jerrom B, Hughes A: Relationship between insight, educational background, and cognition in schizophrenia. British Medical Journal 168:718-722, 1996Google Scholar

5. Buchanan A: A two-year prospective study of treatment compliance in patients with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 22:787-797, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Owen RR, Fischer EP, Booth BM, et al: Medication noncompliance and substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:853-858, 1996Link, Google Scholar

7. Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Rating Manual. New York, Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Schizophrenia Research Unit, 1986Google Scholar

8. Spitzer R, Williams JB, Gibbon J: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, Patient Version. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1987Google Scholar

9. Birchwood M, Smith J, Drury V, et al: A self-report insight scale for psychosis: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:62-67, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Adams SG, Howe JT: Predicting medication compliance in a psychotic population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:558-560, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Weiden P, Rapkin B, Zygmunt A, et al: Postdischarge medication compliance of inpatients converted from an oral to a depot neuroleptic regimen. Psychiatric Services 46:1049-1054, 1995Link, Google Scholar

12. Haywood TW, Kraitz HM, Grosman LS, et al: Predicting the "revolving door" phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:856-861, 1995Link, Google Scholar

13. Ziedonis DS, Truden K: Motivation to quit using substances among individuals with schizophrenia: implication for a motivation-based treatment model. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:229-238, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Awad AG: Subjective response to neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 19:609-618, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Van Putten T, May PRA, Marder SR, et al: Subjective response to antipsychotic drugs. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:187-190, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar