Datapoints: Suicide and Access to Care

In 1998 suicide claimed more than 30,000 lives in the United States and was the eighth leading cause of death for all age groups (1). Despite the significance of this problem as a public health issue, the development of suicide prevention programs lags behind that of many other initiatives (2).

This analysis used data from the 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey (NMFS) (3) to investigate access to health care among people who committed suicide that year. The 1993 survey of decedents' family members was the sixth such survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. It includes 22,957 records that are representative of deaths among people aged 15 and older in 1993. All analyses for the unequally weighted sample were conducted with SUDAAN software.

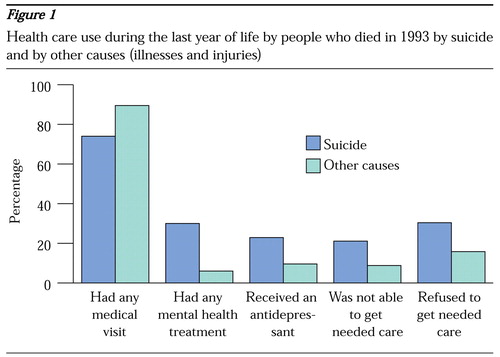

As Figure 1 shows, less than a third of the people who committed suicide had received mental health treatment during their last year of life, and less than a fourth were being treated with an antidepressant medication. Despite the low treatment rates, 76.4 percent of those who committed suicide had a psychiatric diagnosis or exhibited signs of psychosis or depression during their last year of life, according to the respondents, and 48.2 percent had a problem with alcohol or drug abuse.

Compared with people who died of other conditions—illnesses and injuries—those who committed suicide had substantially more difficulty with access to health care. On the basis of the responses, it was estimated that suicide victims were nearly three times as likely to have been unable to get needed care and twice as likely to have refused needed care. The most common barriers to care for this group were trouble paying medical bills, difficulty getting into a treatment facility, and problems finding a doctor.

More than a third of the people who committed suicide had talked about suicide or expressed a wish to die to family members during their last year of life. Nearly 75 percent of those who committed suicide saw a medical professional within their last year of life. This finding is consistent with studies of suicide among elderly persons, which have found that 70 percent of elderly suicide victims had been seen by their primary care provider within a month of death (4).

The NMFS offers many advantages for the study of suicide, including a large sample and clinically confirmed suicide data. However, it also has limitations. First, the data on symptoms of mental illness and diagnoses are brief, and they are obtained by proxy, which may be subject to various types of bias. Second, problems with access to care may be either underreported or overreported, depending on the decedent's course of illness before death.

The results of the NMFS suggest that substantial undertreatment and barriers to care remain for people who are suicidal. Improving access to services may be an important first step in reducing the incidence of suicide in the United States.

Figure 1. Health care use during the last year of life by people who died in 1993 by suicide and by other causes (illnesses and injuries)

1. National Vital Statistics Report. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, July 24, 2000. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/pdf/nvs48_11_8.pdfGoogle Scholar

2. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent Suicide. Washington, DC, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

3. National Mortality Followback Survey: Provisional Data, 1993. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 1998Google Scholar

4. Barraclough BM: Suicide in the elderly: recent developments in psychogeriatrics. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement 6:87-97, 1971Google Scholar