Reexamination of Therapist Self-Disclosure

Abstract

In mental health practice, a commonly held view is that therapist self-disclosure should be discouraged and its dangers closely monitored. Changes in medicine, mental health care, and society demand reexamination of these beliefs. In some clinical situations, considerable benefit may stem from therapist self-disclosure. Although the dangers of boundary violations are genuine, self-disclosure may be underused or misused because it lacks a framework. It is useful to consider the benefits of self-disclosure in the context of treatment type, treatment setting, and patient characteristics. Self-disclosure can contribute to the effectiveness of peer models. Self-disclosure is often used in cognitive-behavioral therapy and social skills training and might be useful in psychopharmacologic and supportive treatments. The unavoidable self-disclosure that occurs in non-office-based settings provides opportunities for therapeutic deliberate self-disclosure. Children and individuals who have a diminished capacity for abstract thought may benefit from more direct answers to questions related to self-disclosure. The role of self-disclosure in mental health care should be reexamined.

Therapist self-disclosure has traditionally been viewed as forbidden. It was generally thought that self-disclosure should be minimized and its dangers closely monitored. In light of changes in medicine, mental health care, and society, we have reexamined this view and challenge the notion that self-disclosure is inherently harmful. In many clinical situations, considerable clinical benefit may stem from therapist self-disclosure (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11). Although the dangers of boundary violations are genuine, we are concerned that self-disclosure is underused or misused because it lacks a framework. We suspect that therapeutic use of self-disclosure is common but that the historical prohibition of self-disclosure makes it one of the "Don't ask, don't tell" practices of psychotherapists (12). Thus we offer a perspective that the clinician can use in considering the appropriate use of self-disclosure.

Self-disclosure can be defined as any behavior or verbalization that reveals personal information to the patient about the clinician. Such self-disclosure has been classified as unavoidable, accidental, or deliberate (13). The risks associated with self-disclosure and the dangers of boundary violations have been amply discussed in the literature (14,15,16,17,18), and it is not our purpose to review them here. We aim to establish a framework for the therapeutic use of deliberate clinician self-disclosure rather than unavoidable or accidental self-disclosure. We first examine the historical context of self-disclosure and then explore more contemporary considerations.

The role of self-disclosure in classical psychoanalytic technique

Freud's ideas rested on a foundation constructed by his medical predecessors. A powerful model for boundaries was aseptic surgery, in which protective barriers between the physician and the patient prevented the transmission of infection. Victorian cultural values and social norms reinforced and sometimes extended the scientific view that it was paramount to observe the inner workings of the patient's mind without letting the act of observation alter the subject. Self-disclosure was thought to result in gratification of patients' wishes rather than analysis of them (4).

In addition, therapist self-disclosure comes with the risk that the territory of inquiry will be shifted from the patient to the physician. The psychoanalytic stance of nondisclosure was intended to allow the patient's projections to be more readily identified and analyzed in the transference. Hence stringent prohibitions against self-disclosure in analytic work emerged, culminating in the psychoanalytic concepts of anonymity, abstinence, and neutrality. The therapist became responsible for maintaining nondisclosure and protecting the boundary between the patient and the therapist (19).

The role of the therapist examined

The literature acknowledges that complete non-self-disclosure is a myth; even the most conservative analysis reveals much about the therapist. The therapist's choice of which of the patient's comments to respond to as well as his or her ability to empathize—as conveyed by interpretation, body language, and tone of voice—tell the patient a great deal about the therapist (20). Renik (20) argued for "a delicate, judicious balance between asymmetry and mutuality" and proposed that self-disclosure sometimes clarifies a point in the real world and conveys the therapist's respect for the patient as a mature collaborator in the therapeutic endeavor. Referring to the "pretense of anonymity," Renik stated that the issue is not whether the analyst self-discloses, but according to what principles. In fact, writers in the analytic field since Freud have attempted to incorporate elements of self-disclosure into theoretical models of psychoanalytic treatments that involve revealing countertransferance reactions in the interests of the therapy (21,22).

Pizer (13) conceptually divided self- disclosure into three types: inescapable, inadvertent, and deliberate. Inescapable self-disclosures occur when real events in the therapist's life—for example, pregnancy—affect the environment of the therapy. Inadvertent self-disclosures occur in the context of the transference-countertransference dyad and include tone of voice and expressions of empathy.

Pizer offered only vague comments about deliberate self-disclosures, suggesting that they "might contribute [to] or indeed open the intersubjective and intrapsychic spaces between therapist and patient, thereby extending the potential for movement, for growth, for further didactic, and ultimate termination." Andersen and Anderson (23) conducted a factor analysis and found that deliberate self-disclosures could be subdivided into three types: disclosure of information related to the personal identity and experiences of the therapist, disclosure of emotional responses, and disclosure of professional experiences and identity.

Other authors, including Greenson, Wexler, and Ferenczi, have maintained that it is important to have a relationship that "feels real" in order for the patient to build a therapeutic alliance with the therapist (24). Winnicott (25) viewed therapy as a creative process that could not move forward unless the patient felt some attachment to the therapist. Such an attachment was necessary in order for the patient to take healthy risks—to change—later in the treatment. Thus even in more traditional therapeutic modalities, self-disclosures occur regularly and may have therapeutic value.

Gutheil and Gabbard (15,16) pointed out that boundary issues are often misunderstood and approached with rigidity. Cautioning against such rigidity, they also underscored the dangers of revealing information such as personal problems, dreams, fantasies, and specific details of vacations or family births and deaths. They believed that such self-revelation could burden the patient and that it "reverses the roles of the dyad." Gabbard and Nadelson (26) warned that although some self-disclosure may improve therapist-patient rapport, excessive self-disclosure with role reversal may initiate a downward spiral into more serious boundary violations, such as sexual involvement.

Although they did not explicitly state it, these authors suggested that one distinguishing feature of appropriate versus inappropriate self-disclosure is the therapist's motivation. They allowed for the use of self-disclosure when it is in the interest of the patient's treatment.

Models

The literature provides little in the way of effective models for the therapeutic use of self-disclosure. Generally the focus is on reduction of harm when disclosure has already occurred or is inevitable rather than on therapeutic benefit. Self-disclosure models tend to fall into two groups. Traditional psychodynamically oriented clinicians profess adherence to a model in which self-disclosure is largely discouraged and is limited to very specific situations. In contrast, "humanistic and eclectic" therapists favor free and open self-disclosure and emphasize that therapist anonymity is impossible. Gutheil and Gabbard (15) suggest a cautious stance between the two models—they acknowledge that sometimes deliberate self-disclosure is acceptable but give little guidance as to when and how to disclose, other than following Karl Menninger's advice to "be human" (15).

A task force of the Massachusetts Psychiatric Society worked with the Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine to develop guidelines for the maintenance of boundaries in psychotherapy (19). This group concluded that treatment could occur in the therapist's home as long as the treatment setting was away from the therapist's general living quarters. The task force took the conservative view that self-disclosure should be minimized except in the case of information about the therapist's training and credentials. It discussed the spread of self-disclosure from the substance abuse treatment model to other settings, such as sexual-orientation groups, but cautioned that even in these settings the therapist should not disclose specific details.

A staff-recipient relations working group of the New York State Office of Mental Health proposed a model policy on relationships between staff and service recipients in which the concept of "exploitation of the recipient" defined boundary or ethical violations. The group explicitly outlined situations in which exploitation occurred (27). However, self-disclosure was not the focus and might or might not be associated with exploitation. Simon and Williams (28) acknowledged the inevitability of reduced anonymity in small communities and rural areas. They warned against undue patient burden and potential boundary violations that occur when personal and professional roles become blurred, especially in the case of unskilled therapists.

Research

Little research has been conducted on the effects of self-disclosure on the attitudes of patients and therapists. A 1974 study found no relationship between the willingness of the "audience"—the therapist—and the "subject"—the patient—to self-disclose (29). Patients' expectations about the appropriateness of therapist self-disclosure influenced their reactions in the event of self-disclosure (30). Patients who expected their therapist to self-disclose revealed more information to highly disclosing therapists than to less disclosing therapists. Conversely, patients who did not expect their therapist to self-disclose tended to reveal less information to highly disclosing therapists. Dies and Cohen (31) surveyed graduate psychology students in a group therapy setting and found that the utility of self-disclosure depended on its timing and context.

Previous work has suggested that there is wide variability in the use of self-disclosure in treatment (24,32). Rosie's anecdotal study (24) suggested that more experienced therapists are more likely to self-disclose. Simon (32) found that therapists' theoretical orientation was the major determinant of self-disclosure. Highly disclosing therapists viewed the focus of the psychotherapy process as an interconnection between the therapist and the patient, whereas less disclosing therapists focused on working through patients' projections. Highly disclosing therapists believed that an attitude of honesty and equality between the therapist and the patient was conveyed by therapist self-disclosure. Less disclosing therapists believed that the "realness" of the therapy was related to empathy, warmth, and attentiveness but not to self-disclosure. Both groups identified several criteria as relevant to decisions about deliberate self-disclosure: modeling and educating, fostering the therapeutic alliance, validating reality, and fostering the patient's sense of autonomy.

Changing rules with changing times

Changes in society and medicine have changed self-disclosure practices among mental health professionals. First, the public has become more accustomed to self-disclosure in the media—for example, the intimate confessions of celebrities and authority figures. Even psychiatrists and mental health professionals have a greater media presence and may be quoted in the newspapers and on television. Second, a variety of effective treatment modalities that are not constrained by the need for anonymity have arisen, including psychopharmacology and cognitive-behavioral therapy (2,3,5,7,11,33). The self-help movement for substance abuse treatment is based on a premise of shared experience and self-disclosure (4). Finally, a variety of community-based interventions—for example, assertive community treatment—place mental health professionals in non-office-based environments that promote nontraditional interactions and exchanges.

Societal changes in attitudes toward clinicians and the clinician-patient relationship have created a variety of pressures to self-disclose. "Patients" have become "consumers," and "clinicians" have become "providers." The consumer-patient, equipped with information, is now empowered to question the clinician-provider and to expect answers. The questions may extend beyond the technical aspects of treatment and into the personal realm. Furthermore, the boundaries between "professional" and "personal" are blurred when consumers believe that they have a right to know whether therapists' personal experiences enable them to be empathic and effective.

Market forces have also altered the traditional power balance, which formerly favored the therapist but now favors the patient. Therapists may feel obliged to answer patients' questions to maintain patient satisfaction. Moreover, technology has enabled patients to obtain information about therapists even if the therapists do not reveal such information directly.

The changing demographic characteristics and diagnoses of patients receiving mental health services constitute another relevant phenomenon. Deinstitutionalization has caused more people who have severe mental illnesses to receive treatment in the community, and outpatient clinicians are treating a broader mix of patients who require more directive interventions (34). Overall, more people are receiving mental health care because of broader insurance coverage, improved psychopharmacological and psychosocial treatments, greater numbers of providers in all disciplines, and some reduction in the stigma associated with mental illness. The participation of patients and therapists of different cultures has introduced culture-specific issues about sharing personal information, which demands a more flexible approach to self-disclosure.

A new perspective

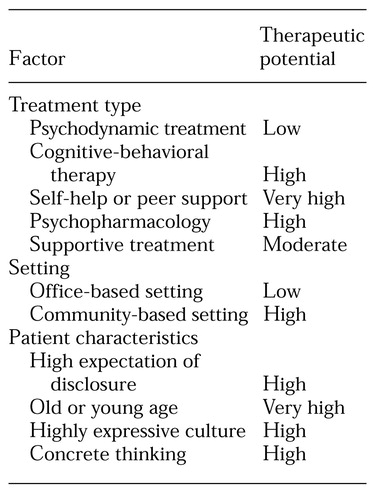

Instead of focusing exclusively on the potential harm of deliberate self-disclosure, therapists should consider whether it might be helpful for a particular patient in a particular treatment. This new question assumes that self-disclosure as a psychotherapeutic technique can enhance treatment. In Table 1 and in the following sections, the potential benefit of the use of self-disclosure with different types of treatment, in different settings, and with different patient groups is considered.

Treatment type

Several types of treatment provide opportunities for therapeutic self-disclosure. Self-disclosure and mutual support contribute to the effectiveness of peer models, such as 12-step programs and self-help groups. Many of these models have entered the therapeutic mainstream and include clinician-facilitated self-help groups. Such treatments often focus on specific behaviors or life experiences, such as addiction, bereavement, parenting, divorce, trauma, or physical illness. The therapist may disclose past experiences as part of the ethic of sharing. Such disclosure alleviates the patient's shame and embarrassment, provides positive modeling, normalizes the patient's experience, and provides hope. Questions remain as to whether the therapist should self-disclose about current problems or difficulties and about topics outside of the specific focus of the group.

In cognitive-behavioral therapy and social skills training, self-disclosure can be used to model coping strategies and problem-solving techniques. For example, self-disclosure is one of the suggested techniques in dialectical behavioral therapy. Linehan's treatment manual (11) describes "self-involving" self-disclosure, in which the therapist reveals his or her immediate personal reactions to the patient, and "personal self-disclosure," in which the therapist gives the patient information about himself or herself that may not necessarily relate to the therapy or the patient. Linehan's manual describes the circumstances and situations in dialectical behavioral therapy under which such self-disclosures are useful. Another example of the utility of self-disclosure involves metaphor, such as when a therapist helps the patient by saying, "It's like when my son was learning to ride a bike. He tried and tried, and suddenly he just got it."

In psychopharmacologic treatments, self-disclosure may increase rapport, enhance the therapeutic alliance, and increase compliance with medications. Answering questions in a straightforward fashion, the psychopharmacologist provides concrete explanations about the patient's illness and medications. Exploration and interpretation are usually confined to issues pertaining to patient's fears about side effects. In the same way that a cardiologist might respond directly to a patient's question about whether the cardiologist personally would take antihypertensives, so might psychopharmacologists answer questions about whether they or a family member have taken a psychotropic medication. The answer would depend on the context and the clinician's own comfort level.

The limited role of self-disclosure in exploratory psychodynamic treatment contrasts with its potential utility in supportive therapies. In supportive therapy—even psychodynamically oriented supportive therapy—self-disclosure can have many of the same therapeutic benefits derived from its use in cognitive-behavioral and psychopharmacologic treatments. In a wide range of reality-based, present-focused treatments, exploration and interpretation of the transference from a neutral standpoint may not be central components of therapeutic efficacy. Miller and Stiver (35) challenge therapists to use deliberate self-disclosure as part of the therapeutic armamentarium.

Setting

In addition to the type of treatment, treatment setting also introduces opportunities for therapeutic self-disclosure. Setting refers to the actual treatment location and the nature of the community in which treatment occurs. Treatments that take place outside the office, in particular, involve inescapable and inadvertent self-disclosure. During a home visit, the clinician may need to reveal information about food preferences, food allergies, or religious restrictions if the patient offers food. The clinician then needs to integrate these pieces of information into the treatment in a positive and helpful manner. Refusal to self-disclose might seem rude or offensive.

Similar issues arise when treatment is delivered in a small or rural community in which even office-based treatments may be complicated by inescapable or inadvertent disclosure. The patient may be the clinician's grocer or a member of the same church or parent-teacher association. In such cases the patient has probably already learned a great deal about the therapist both directly and indirectly. The clinician can weave such knowledge into the therapeutic experience rather than feigning ignorance, and this approach may require deliberate self-disclosure (35).

Finally, it is important to remember that in addition to geography, a community may be defined by certain demographic, ethnic, religious, sexual, or personal characteristics. When patients want to be treated by someone who shares such a characteristic, multiple opportunities for self-disclosure emerge.

Patient characteristics

The patient's age, sex, educational level, socioeconomic status, cultural background, and personality merit consideration in decisions about self-disclosure. Children and adolescents and individuals who have mental retardation, dementia, or a diminished capacity for abstract thought tend to ask more personal questions and may benefit from more direct, concrete answers to questions related to self-disclosure. Adolescents may feel demeaned when a therapist does not respond directly to a question. Refusal to answer the question of an elderly patient may be viewed as disrespectful. In addition, patients from more emotionally expressive cultures often expect a more personal form of social interaction.

The clinician should also consider the patient's previous treatment experiences. A patient who encounters a self-revealing therapist after years of more traditional analysis may be confused. On the other hand, a patient who is undertaking long-term exploratory psychotherapy after receiving a supportive or biologically oriented treatment may be angered or daunted by a therapist's more withholding stance. In such situations, a more gradual transition, with repeated orientation to the new "rules," may be needed.

Similarly, persons who have been abused by a therapist by way of boundary violations will need to learn to maintain "normal" boundaries in relationships. This need generally must be addressed in treatment in order to improve patients' interpersonal relationships. In such cases, self-disclosure can be used both for modeling—teaching, through example, the skill of appropriate self-disclosure—and for repair—enabling these patients to experience maintenance of boundaries through helpful self-disclosure in a clinical relationship.

Conclusions

Clinicians should recognize the benefits of self-disclosure as well as its dangers. This is especially true for clinicians who work in self-help or peer formats, cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychopharmacologic management, and supportive therapy. It is also especially relevant for community settings and among subgroups of patients who have high expectations of self-disclosure or concrete thinking. Nevertheless, the choice of whether to self-disclose should be an active decision that is balanced against the risks, and the decision should always be based on the patient's best interests. Skill and sometimes supervision are necessary for making the best choices about self-disclosure.

Consideration of the therapeutic benefits of self-disclosure has been hindered by the association between self-disclosure and flagrant boundary violations. We do not dispute the fact that inappropriate self-disclosure is a component of many harmful boundary violations. However, it is erroneous to conclude that self-disclosure inevitably leads to boundary violations. Such a view has diminished our therapeutic repertoire by limiting the potential benefits of clinician self-disclosure. Psychotherapy research should include the study of self-disclosure as one of the prospective active ingredients of the therapeutic process. In these rapidly changing times, we must be open to addressing the positive aspects of therapist self-disclosure in developing new rules for our new roles.

The members of the Psychopathology Committee of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry are Lisa Dixon, M.D., M.P.H., David Adler, M.D., Devra Braun, M.D., Rebecca Dulit, M.D., Beth Goldman, M.D., M.P.H., Samuel Siris, M.D., William Sonis, M.D., Paula Bank, M.D., Richard Hermann, M.D., M.S., Victor Fornari, M.D., M.S., and Jon Grant, M.D. Send correspondence to Dr. Dixon at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland, 701 West Pratt Street, Room 476, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Factors associated with a greater therapeutic potential of therapist self-disclosure

1. Dryden W: Brief Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy. Chichester, England, Wiley, 1995Google Scholar

2. Freeman A, Pretzer J, Fleming F, et al: Clinical Applications of Cognitive Therapy. New York, Plenum, 1990Google Scholar

3. George RL: Counseling the Chemically Dependent: Theory and Practice. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1990Google Scholar

4. Mallow AJ: Self-disclosure: reconciling psychoanalytic psychotherapy and Alcoholics Anonymous philosophy. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 15:493-498, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Margolin G: Marital therapy: a cognitive-behavioral approach, in Psychotherapists in Clinical Practice: Cognitive and Behavioral Perspectives. Edited by Jacobson NS. New York, Guilford, 1987Google Scholar

6. Pociluyko PJ: The therapist's use of self-disclosure in counseling and psychotherapy: implications and considerations for its use. Maryland State Medical Journal 28(5):77-82, 1979Google Scholar

7. Rimm DC, Masters JC: Behavior Therapy: Techniques and Empirical Findings. New York, Academic, 1979Google Scholar

8. Schuyler D: A Practical Guide to Cognitive Therapy. New York, Norton, 1991Google Scholar

9. Schwartz A: The Behavior Therapies: Theories and Applications. New York, Free Press, 1982Google Scholar

10. Werner HD: Cognitive Therapy: A Humanistic Approach. New York, Free Press, 1982Google Scholar

11. Linehan M: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

12. Jancin B: Movie shines spotlight on therapist self-disclosure. Clinical Psychiatry News 27(6):29, 1999Google Scholar

13. Pizer B: When the analyst is ill: dimensions of self-disclosure. Psychoanalytic Quarterly 64:466-495, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Walker R, Clark JJ: Heading off boundary problems: clinical supervision as risk management. Psychiatric Services 50:1435-1439, 1999Link, Google Scholar

15. Gutheil TB, Gabbard GO: The concept of boundaries in clinical practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:188-196, 1993Link, Google Scholar

16. Gutheil TG, Gabbard GO: Misuses and misunderstandings of boundary theory in clinical and regulatory settings. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:409-414, 1998Link, Google Scholar

17. McHugh PR: Psychotherapy gone awry. American Scholar 63:17-30, 1994Google Scholar

18. Gonsiork JC (ed): Breach of Trust: Sexual Exploitation by Health Care Professionals and Clergy. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1995Google Scholar

19. Hundert EM, Applebaum PS: Boundaries in psychotherapy: model guidelines. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 20:269-298, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

20. Renik O: The ideal of the anonymous analyst and the problem of self-disclosure. Psychoanalytic Quarterly 65:681-682, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Racker H: Transference and Countertransferance. Madison, Conn, International Universities Press, 1968Google Scholar

22. Tauber E: Exploring the therapeutic use of countertransferance data. Psychiatry 17:331-336, 1954Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Andersen B, Anderson W: Counselors' reports of their use of self-disclosure with clients. Journal of Clinical Psychology 45:302-308, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Rosie JS: The therapists's self-disclosure in individual psychotherapy: research and psychoanalytic theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42:901-908, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Winnicott DW: Playing and Reality. London, Tavistock, 1971Google Scholar

26. Gabbard G, Nadelson C: Professional boundaries in the physician-patient relationship. JAMA 273:1445-1449, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Fisher WA, Goldsmith E: Principles underlying a model policy on relationships between staff and service recipients in a mental health system. Psychiatric Services 50:1447-1452, 1999Link, Google Scholar

28. Simon RI, Williams IC: Maintaining treatment boundaries in small communities and rural areas. Psychiatric Services 50:1440-1446, 1999Link, Google Scholar

29. Wilson MN, Rappaport J: Personal self-disclosure: expectancy and situational effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42:901-908, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Derlega VJ, Lovell R, Chaikin AL: Effects of therapist disclosure and its perceived appropriateness on client self-disclosure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 44:866, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Dies RR, Cohen L: Content considerations in group therapist self-disclosure. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 26(1):71-88, 1976Google Scholar

32. Simon JC: Criteria for therapist self-disclosure. American Journal of Psychotherapy 42:404-415, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Pociluyko PJ: The therapist's use of self-disclosure in counseling and psychotherapy: implications and considerations for its use. Maryland State Medical Journal 5:77-82, 1979Google Scholar

34. Pincus HA, Zarin DA, Tanielian TL, et al: Psychiatric patients and treatments in 1997. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:441-449, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Miller JB, Stiver I: The Healing Connection. Boston, Beacon, 1997Google Scholar