Measuring Clients' Satisfaction With Self-Help Agencies

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Clients' satisfaction with their involvement in treatment decisions has been largely overlooked in the formulation of satisfaction measures. The authors describe the development of a scale that assesses clients' satisfaction with services and with their involvement in treatment decisions. METHODS: Long-term users of four client-operated mental health self-help agencies were interviewed at baseline (N=310) and six months (N=248) using the 11-item Self-Help Agency Satisfaction Scale (SHASS). The scale was developed on the basis of consumers' input about their satisfaction with services and their involvement in treatment decisions. To explore the relationship between satisfaction as measured by the SHASS and outcomes, the six-month interview included four outcome measures—independent and assisted social functioning, symptom severity, and a sense of personal empowerment. Internal consistency, stability, and discriminant validity were evaluated. RESULTS: Factor analyses confirmed that the SHASS has two subscales, one assessing service satisfaction and the other assessing satisfaction with involvement in treatment decisions. The scale and its subscales showed high internal consistency, moderate stability, and discriminant validity. The SHASS subscales showed modest associations with two of four outcome measures—assisted and independent social functioning. CONCLUSIONS: The SHASS is a brief instrument that can be used to measure clients' satisfaction with their involvement in treatment in mental health self-help agencies.

The self-help movement represents one of the most significant developments in the provision of mental health services (1,2,3,4). Involving consumers as active participants in addressing their treatment needs has become a key element in health care practice (5).

Self-help agencies are mental health service organizations operated primarily by consumers with psychological disabilities. These agencies have been increasingly used under managed care as a source of inexpensive services. They are proliferating throughout the country, and state legislatures and private foundations are lending them increased support (6,7). Given cost-cutting trends, the self-help model seems to be one of the few components of the mental health system exhibiting consistent growth.

However, questions have been raised about the effectiveness and the types of outcomes that self-help agencies can deliver (8). As part of the effort to enhance treatment outcomes, clients' satisfaction with services has become one of the criteria most frequently used to evaluate program success. This paper describes the development of a scale measuring clients' satisfaction with being actively involved in a self-help agency and the services they receive.

Two of the instruments most frequently used in service satisfaction research, the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (9) and the Service Satisfaction Scale (10), focus primarily on satisfaction with types of services. Ruggeri (11) reviewed 16 studies in which mental health organizations assessed clients' satisfaction with services as a whole and with specific service characteristics, such as the physical environment and types of intervention. All but two studies examined only satisfaction with the types of services rather than clients' satisfaction with their role in making care-related decisions. A similar focus was reflected in the majority of research surveyed for this paper (12,13,14,15,16,17).

Elbeck and Fecteau (18) conducted a factor analysis of a 50-item questionnaire about service satisfaction that was developed on the basis of focus-group discussions with psychiatric inpatients. They found that the items diverged into two main factors, behavioral autonomy and supportive care. The primary objective of the self-help agency is to help clients develop behavioral autonomy—to help them become actively involved in their care. The instrument described in this paper, the Self-Help Agency Satisfaction Scale (SHASS), is used to measure both clients' satisfaction with their involvement in the helping process—the autonomy dimension, and their satisfaction with the services received—the support dimension.

Methods

Subjects

This study is part of a larger investigation of users of mental health self-help agencies and the agencies themselves (19,20,21,22,23). Participants in the survey were long-term adult users of four client-run self-help agencies in the San Francisco Bay area. Staff—who were themselves clients—volunteers, and other members were interviewed between 1992 and 1993. Only participants who had used the self-help agency at least 12 times over a three-month period were included. During the month before the initial interview, the study participants visited the self-help agency an average of 16.6 times. At the six-month follow-up, they had visited the agency 13.1 times in the previous three months.

A total of 321 baseline interviews were initiated, and 310 were completed (97 percent). A total of 248 participants completed six-month interviews (80 percent of the original sample). No participant who could be located refused a follow-up interview.

The mean±SD age of the 310 participants was 38±8.44 years. A total of 222 (72 percent) were male, and 269 (87 percent) had confirmed DSM-III-R diagnoses. At the time of their first interview, 143 participants (46 percent) were living on the streets or in a shelter. The remaining 167 (54 percent) were often unstably housed.

Interviews were conducted by both mental health professionals and clients not currently active in the target agencies. The interviewers were trained at the Center for Self-Help Research at the Public Health Institute in Berkeley, California.

Study sites

The four self-help agencies were located in urban settings. They provided mutual support groups, drop-in space, survival resources, assistance in obtaining shelter, case management, financial planning, payeeship services, substance abuse and peer counseling, advocacy, employment assistance, and information and referral. Most paid staff members were drawn from the ranks of program clients or had shared similar experiences of poverty, homelessness, and institutionalization.

Volunteer jobs within the agencies were provided with the aim of offering members the opportunity to help others, to develop mainstream work habits, and to participate in organizational decision making. Staff, volunteers, and clients at all four agencies also engaged in a variety of ad hoc political and social-change activities.

Instruments

The Center for Self-Help Research developed a structured interview schedule for the study. The items were based on discussions between consumers in self-help agencies and mental health professionals. The items were reviewed by the center's consumer advisory group and the staff of the four agencies.

Four standard outcome measures were used to assess the predictive utility of the SHASS.

The Independent Social Functioning Scale. The Independent Social Functioning Scale (ISFS) is a modified version of Segal and Aviram's External Social Integration Scale (24), which measures "the extent to which an individual participated in and made use of the community in a self-initiated manner and without the help of others" (25). Segal and Kotler (25) reported construct validation of the ISFS and good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=.95).

The Assisted Social Functioning Scale. The Assisted Social Functioning Scale (ASFS) assesses the same types of community involvement as the ISFS while assessing whether the involvement was in some way enabled by a helper. The internal consistency of the ASFS has been reported to be good (Cronbach's alpha=.94) (25).

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), developed by Overall and Gorham (26), is a symptom-based index that has frequently been used in drug trials (26,27) and was used by Segal and colleagues (19,24) in their studies of former psychiatric patients in board-and-care homes. Good interrater reliability has been reported (r=.9) (24), with internal consistencies varying from .79 (24) to .86 (25).

The Personal Empowerment Scale. The Personal Empowerment Scale (20) measures the degree of perceived control over common life activities, including obtaining shelter, income, and services. It also measures the ability to minimize the occurrence of unwanted events such as assault or homelessness.

Statistical methods

Item analysis for the SHASS. Factor analysis of item content related to satisfaction with various aspects of the self-help agency's program—including the physical environment, organization of services, staff competence and attitudes, types of intervention, and clients' involvement in the helping process—was used to construct the SHASS. The items used a 5-point Likert format, with 1 indicating very dissatisfied and 5 indicating very satisfied. The factor analysis, which employed principal-axis factoring with Eigenvalues set at 1, was conducted at baseline and at six months. Simple structure was sought via rotation with varimax and Kaiser normalization procedures. The communality estimate used was multiple R2.

Reliability and stability analyses. Internal consistencies (Cronbach's alpha) and stability coefficients (Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient) were computed across a six-month period.

Construct validation. One concern that has been raised about using satisfaction as an outcome measure is that respondents' ratings of satisfaction with the organization and services may be confounded by their global sense of well-being. To ensure that our measure of satisfaction with the agency was distinct from a respondent's general level of life satisfaction, we included a measure of satisfaction with quality of life based on three subscales—housing, income, and social network. We then factor analyzed the subscale scores of both the SHASS and the quality-of-life measure, using the same procedures described above, to determine whether the subscales represented different dimensions of satisfaction—that is, whether they demonstrated discriminant validity.

Predictive utility. We used partial correlation coefficients to determine the relationship between client satisfaction at baseline and each of the four outcomes measured at six months, after controlling for baseline status on each outcome measure.

Results

Item analysis

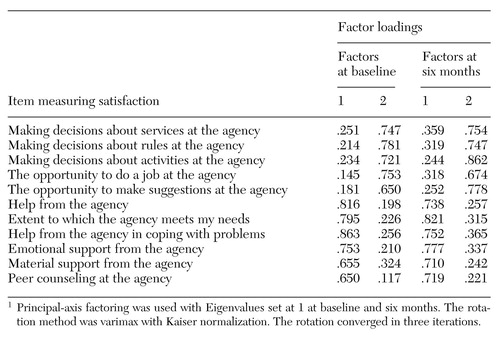

Table 1 shows that the item content on the SHASS breaks down into two distinct factors. The first measures satisfaction with active involvement in the agency, and the second measures satisfaction with the services or support received. Principal-axis factoring accounted for 60.7 percent of the variance extracted from the two factors at baseline and 66.8 percent of the variance at follow-up. Eigenvalues were equal to or greater than one. Varimax, with Kaiser normalization rotations to simplify structure, was achieved with three iterations. As Table 1 shows, the analyses yielded almost identical factors at baseline and follow-up. Results confirmed our two-factor hypothesis.

Reliability and stability analyses

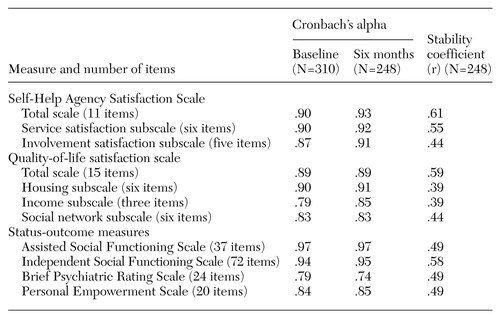

SHASS. The SHASS includes 11 items. Six items constitute the service subscale and five the involvement subscale. Table 2 presents the reliability and stability characteristics of the full scale and both of its subscales. Internal consistencies varied from .87 to .90 at baseline and from .91 to .93 at follow-up. Stability coefficients varied from .44 to .61.

Quality-of-life measure.Table 2 also reports measurement characteristics of the quality-of-life measure and its three subscales. Internal consistencies varied from .79 to .90 at baseline and from .83 to .91 at follow-up. Stability coefficients ranged from .39 to .59.

Discriminant validity

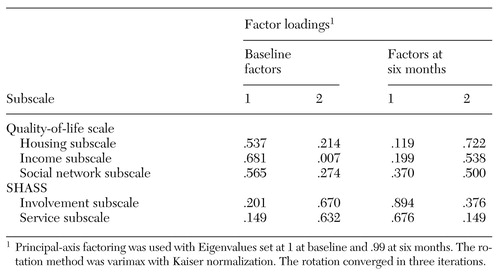

Table 3 shows results of the factor analyses of the quality-of-life subscales and the SHASS subscales at baseline and follow-up, with factor loadings reflecting a rotated factor matrix. Both at baseline and at follow-up, two different factors emerged—a SHASS subscale factor and a quality-of-life factor. These results support the hypothesis that the SHASS measures a construct distinct from general life satisfaction.

Utility in predicting outcomes

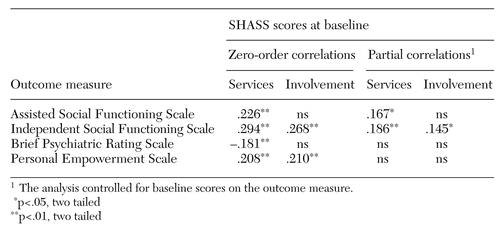

The reliability and stability coefficients of the four status-outcome measures are reported in Table 2. Table 4 shows the zero-order correlations and partial correlations of the two SHASS subscales and the four status-outcome measures. Six of the eight zero-order correlations indicated a significant relationship between baseline satisfaction and follow-up outcome scores. However, only three relationships were significant when the analyses controlled for baseline scores on the outcome variable.

The partial correlation between scores on the SHASS service subscale and the ISFS, adjusted for baseline scores on the ISFS, was significant, as was the correlation with the ASFS score. For the SHASS involvement subscale, only the partial correlation with the ISFS was significant.

Discussion

The findings support the utility of a new measure of client satisfaction for use in self-help agencies and suggest the need for further research on the Self-Help Agency Satisfaction Scale to determine its usefulness in other mental health settings, including outpatient settings, community-based care, and inpatient settings. It was in an inpatient setting that Elbeck and Fecteau (18) first distinguished the behavioral autonomy and support dimensions of satisfaction that we have validated with the development of the SHASS.

The SHASS is brief—11 items—and easy to administer. It measures clients' satisfaction with services and with their involvement in their own care. These two factors have been identified as the most salient in evaluating the provision of mental health services (18). Particularly in the context of inpatient care, which can erode an individual's sense of control over many life domains, maximizing involvement in treatment decisions might prove useful in mitigating some of the effects of institutionalization. The SHASS and its two subscales showed a high degree of internal consistency. The moderate degree of stability across a six-month period attests to its reactivity to change in clients' organization-related experiences.

With the deletion of a single item—satisfaction with the opportunity to do a job—and removal of the word "peer" preceding "counseling," this scale may work in most mental health settings. The elimination of the job item has a minimal effect on the scale's internal consistency (Cronbach's alphas of .90 at baseline and .93 at follow-up for the total scale and .89 at baseline and .92 at follow-up for the scale without the item).

A key factor in the validation of the scale was our ability to show its independence from more global measures of satisfaction with quality of life at baseline. The distinction between these measures was less strong at six months, possibly because participation in a self-help agency, especially satisfaction with the social network, increasingly defines the quality of life for long-term users of self-help agencies.

If the SHASS has a weakness, it is what Ruggeri (11) called sensitivity—the ability to assess satisfaction with specific program components. The SHASS could be expanded, although that might affect its convenience of application.

Finally, consumer satisfaction as an outcome that has value in and of itself is open to question. Research has demonstrated cross-sectional relationships between satisfaction measures and status-outcome variables, showing that status measures representing the primary objectives of the helping effort are associated with satisfaction levels at follow-up. However, such studies have yet to fully explore the role of satisfaction with services in mediating treatment outcomes (28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38). Because participants were recruited into this study after a minimum of three months of participation in the self-help agencies, the relationship of satisfaction at the time of recruitment and outcomes measured six months after enrolling in the study was explored. Dissatisfaction with traditional mental health programs is one of the primary reasons that self-help agencies have been established. Thus the discovery of an association between satisfaction during a service period and outcomes has special significance.

The study found a modest relationship between the satisfaction subscales and two treatment outcomes. Participants' scores on the SHASS service satisfaction subscale were significantly associated at follow-up with assisted and independent social functioning. Scores on the SHASS involvement subscale were significantly associated with independent social functioning at follow-up. Further study is needed to determine whether these two dimensions of satisfaction have a mediator effect on client outcomes.

Conclusions

Central to the operation of self-help agencies is the active involvement of clients in the helping process. This study focused on the development of a multidimensional measure of satisfaction with self-help agencies that included subscales reflecting both satisfaction with active involvement in the agency and satisfaction with the support or services received. The SHASS exhibited high internal consistencies, moderate stability, and discriminant validity with measures of satisfaction with quality of life. In addition, the SHASS subscales showed modest associations with two of four measures of client outcomes—assisted and independent social functioning.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01-NM-47487 and training grant HH-18828 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Segal is professor and director of the Mental Health and Social Welfare Research Group in the School of Social Welfare, 120 Haviland Hall (MC#7400), University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-7400 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Redman is research associate and Dr. Silverman is program director of the Center for Self-Help Research of the Public Health Institute in Berkeley.

|

Table 1. Factor loadings at baseline and six months for items on the Self-Help Agency Satisfaction Scale1

1 Principal-axis factoring was used with Eigenvalues set at 1 baseline and six monthsThe rotation method was varimax with Kaiser normalization. The rotation converged in three iterations.

|

Table 2. Intenal consistency and stability coefficients for the Self-Help Agency Satisfaction Scale, the quality-of-life measure, and status-outcome measures for interview participants at baseline and six months

|

Table 3. Factor loadings for subscales of the quality-of-life scale and the Self-Help Agency Satisfaction Scale (SHASS) at baseline and six months

|

Table 4. Correlations and partial correlations of the two subscales of the Self-Help Agency Satisfaction Scale (SHASS) and four outcome measures at six-month follow-up

1. Consumer Involvement in Mental Health and Rehabilitation Services. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1989Google Scholar

2. Surgeon General's Workshop on Self-Help and Public Health. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1988Google Scholar

3. Salem DA, Siedman E, Rappaport J: Community treatment of the mentally ill: the promise of mutual help organizations. Social Work 33:403-408, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Polcin DL: Administrative planning in community mental health. Community Mental Health Journal 26:181-192, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Clinton's economic plan. New York Times, Feb 18, 1993, p A14Google Scholar

6. Zinman S, Harp HT, Budd S (eds): Reaching Across: Mental Health Clients Helping Each Other. Riverside, Calif, California Network of Mental Health Clients, 1987Google Scholar

7. Emerick RE: Group structure and group dynamics in the mental health self-help movement: toward a topology of groups. Presented at the Symposium on the Impact of Life-Threatening Conditions: Self-Help Groups and Health Care Providers in Partnership, Chicago, Mar 31, 1989Google Scholar

8. Cooperative Agreements to Evaluate Consumer-Operated Human Service Programs for Persons With Serious Mental Illness. Guidance for Applicants (GFA) SM 98-004. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 1998Google Scholar

9. Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al: Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning 2:197-207, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Greenfield TK, Attkisson CC: Steps toward a multifactorial satisfaction scale for primary care and mental health services. Evaluation and Program Planning 12:271-278, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Ruggeri M: Patients' and relatives' satisfaction with psychiatric services: the state of the art of its measurement. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 29:212-227, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Brown ED: The Role of Expectancy in Rating of Consumer Satisfaction With Mental Health Services. Dissertation Abstracts International 41(1-B):341, 1980Google Scholar

13. Love RE, Caid CD, Davis A: The User Satisfaction Survey: consumer evaluation of an inner-city community mental health center. Evaluation and the Health Professions 1:42-54, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Essex D, Fox J, Groom J: The development, factor analysis, and revision of a client satisfaction form. Community Mental Health Journal 17:226-235, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Salter V, Lynn MW, Harris R: Outcome evaluations of mental health care. Southern Medical Journal 74:1217-1219, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Salter V, Lynn MW, Harris R: Satisfaction with mental health treatment scale. Comprehensive Psychiatry 23:68-74, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Murphy MJ: An Investigation of Facets of Client Satisfaction With Out-Patient Mental Health Service. Dissertation Abstracts International 40(8):39-47, 1980Google Scholar

18. Elbeck M, Fecteau G: Improving the validity of measures of patient satisfaction with psychiatric care and treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:998-1001, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Characteristics and service use of long-term members of self-help agencies for mental health clients. Psychiatric Services 46:269-274, 1995Link, Google Scholar

20. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Measuring empowerment in client-run self-help agencies. Community Mental Health Journal 31:215-227, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Program environments of self-help agencies. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:456-464, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

22. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Social networks and psychological disability and homeless users of SHAs. Social Work in Health Care 25(3):49-61, 1997Google Scholar

23. Segal SP, Gomory T, Silverman C: Health status of homeless and marginally housed users of mental health self-help agencies. Health and Social Work 23:45-52, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Segal SP, Aviram U: The Mentally Ill in Community-Based Sheltered Care. New York, Wiley, 1978Google Scholar

25. Segal SP, Kotler PL: Personal outcomes and sheltered care residence: ten years later. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 63:80-91, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Rhoades HM, Overall JE: The semi-structured Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale interview and rating guide. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 24:101-104, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

28. Ruggeri M, Biggeri A, Rucci P, et al: Multivariate analysis of outcome of mental health care using graphical chain models: the South-Verona Outcome Project 1. Psychological Medicine 28:1421-1431, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Kurtz LF: Measuring member satisfaction with a self-help association. Evaluation and Program Planning 13:119-124, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Allen G, et al: Helping homeless mentally ill people: what variables mediate and moderate program effects? American Journal of Community Psychology 22:661-683, 1994Google Scholar

31. Ruggeri M, Greenfield TK: The Italian version of the Service Satisfaction Scale (SSS-30) adapted for community-based psychiatric patients: development, factor analysis, and application. Evaluation and Program Planning 18:191-202, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Pickett SA, Lyons JS, Polonus T, et al: Factors predicting patients' satisfaction with managed mental health care. Psychiatric Services 46:722-723, 1995Link, Google Scholar

33. Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner BL: Assessment of patient satisfaction: development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Evaluation and Program Planning 6:299-314, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Attkisson CC, Zwick R: The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire: psychometric properties and correlation with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning 5:233-237, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Willer RB, Miller GH: On the relationship of client satisfaction to client characteristics and outcome of treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology 34:157-160, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB, et al: Customer satisfaction and self-reported treatment outcomes among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 49:929-933, 1998Link, Google Scholar

37. Salzer M: Consumer satisfaction (ltr). Psychiatric Services 49:1622, 1998Link, Google Scholar

38. Holcomb WR, Parker JC: Consumer satisfaction: in reply (ltr). Psychiatric Services 49:1623, 1998Link, Google Scholar