Unmet Needs for Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Among Northern Plains American Indian Adolescents

Abstract

Use of mental health and substance abuse services was examined among 109 American Indian adolescents in a Northern Plains reservation community. Each was interviewed to assess psychiatric diagnosis and service use and to determine whether an adult had recognized a problem in the adolescent—a critical determinant of receipt of services. Of the 23 youths who had a disorder, nine (39 percent) reported lifetime service use. Of the 25 who received services, 17 were treated by a school counselor; only one received services from a mental health specialist. Eight of the 25 youths with a psychiatric or substance use diagnosis who did not receive services reported that an adult had recognized a problem.

Our knowledge about met and unmet needs for alcohol, drug, and mental health services among American Indian adolescents is limited. In the only previously published study examining both service use and psychiatric diagnosis among Indian children, Costello and associates (1) reported that just 14 percent of Indian children between the ages of nine and 13 who had a psychiatric diagnosis had received services from a mental health professional in the past three months. This rate was lower than the low rate of 25 percent for white children participating in the same study.

The study reported here adds to the limited literature on the use of substance abuse and mental health services by American Indian adolescents by addressing two issues. First, because of significant epidemiologic, cultural, and service system differences among the 556 federally recognized American Indian tribes, studies of Indian communities other than those examined by Costello and associates are necessary to gain a more complete understanding of the met and unmet needs for these services among Indian youths (2). Second, Costello and colleagues (1) did not report the extent of problem recognition by an adult among the diagnosed youths in their study who did not receive treatment. For an adolescent with a psychiatric or substance use diagnosis, an adult's recognition of a problem may be critical in determining whether the adolescent actually receives treatment (3).

The goal of this study was to describe the use of mental health and substance abuse treatment services among a group of Northern Plains Indian adolescents who participated in a small school-based epidemiologic study. The study also determined the level of problem recognition by an adult and the relationship of diagnosis to both service use and problem recognition.

Methods

Data were collected between March and June 1991. The sample consisted of 109 adolescents who met several criteria. Those included in the sample had participated in a previous school-based epidemiologic project; they were still living on their home reservation and could be located; and they agreed to participate. Of the 113 students from the original study who were located, two refused to participate, and two were deceased. The 109 participants represented 45 percent of the original sample.

Most of the participants were attending school (100 participants, or 92 percent). Half were female (54 participants, or 50 percent). The mean±SD age was 15.6±1.13 years, ranging from 13 to 18 years.

The youths in this study resided in a geographically isolated Northern Plains reservation community that has one of the highest unemployment rates and lowest life expectancies in the nation for both men and women. At the time of data collection, mental health and substance abuse treatment was offered in school-based programs; outpatient, inpatient, and residential programs; and traditional healing services. The majority of these services targeted substance use disorders.

All measures used in the study were derived from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Child Version 2.1 (DISC2.1C) (4,5). The DISC2.1C ascertains the presence, severity, and duration of symptoms in the past six months of a variety of DSM-III-R diagnoses. We developed three summary categories for the 12 mental and substance use diagnoses reported by Beals and associates (4). The anxiety-depressive disorders category included simple and social phobia, separation anxiety, overanxious behavior, major depressive disorder, and dysthymic disorder. Disruptive behavior disorders included attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorders, and oppositional defiant disorder. Substance use disorders included abuse of and dependence on alcohol, marijuana, and other substances.

Lifetime service use was measured by summarizing each adolescent's responses to questions about use of services for disorders in each DISC2.1C diagnostic module. Only respondents who reported a specific number of symptoms in each module were asked further questions about services use. Of the 109 participants, six did not report enough symptoms to be asked any of the service use questions.

Youths were also asked from whom they received services, and their responses were classified into two categories. The category of mental health specialists included psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers. The category of other mental health providers included family therapists, alcohol and drug counselors, other therapists, school guidance counselors, general health care providers (nurses, pediatricians, and family doctors), and traditional healers.

Youths who were asked questions about service use but who did not receive services were also asked whether any parent, other caretaker, teacher, or employer ever thought they needed to see someone for their symptoms. Adolescents who answered any of these questions affirmatively were considered to have had a problem recognized by an important adult.

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows, version 6.1. Two-tailed t tests and chi square tests were used to examine potential differences in service use and problem recognition by age, gender, and the presence of any mental or substance use disorder. Unadjusted odds ratios were calculated to reflect the relative odds of service use and problem recognition among youths in each diagnostic category compared with youths not included in that category. In these comparisons, the small sample size did not permit meaningful statistical analyses.

Results

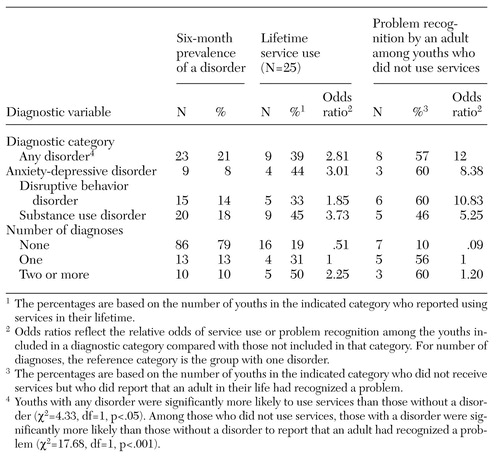

Table 1 summarizes six-month prevalence, lifetime service use, and recognition of a problem by an adult for the various diagnostic categories. As reported previously by Beals and associates (4), 23 of the 109 youths (21 percent) were diagnosed as having a mental or substance use disorder, or both, in the past six months. Twenty-five of the 109 respondents (23 percent) reported using services for symptoms of mental or substance use disorders during their lifetime. No significant differences were found in service use by gender or age.

Nine of the 23 youths diagnosed as having a disorder (39 percent) had received mental health or substance use services for their symptoms during their lifetime.

Of the 25 adolescents who used services, 17 reported being treated by a school counselor. Two reported seeing a general health provider, and two saw a traditional healer. Only one adolescent reported receiving services from a mental health specialist; four reported seeing other counselors and therapists.

Among the adolescents who did not use mental health or substance abuse services, the number in each diagnostic category whose problem was recognized by an adult is also reported in Table 1. Fifteen youths who had never used services reported that a parent or other caregiver, a teacher, or an employer had thought they were in need of services. Eight of these youths (57 percent) were assessed by the DISC2.1C as having a disorder in the past six months. The rate of problem recognition by an adult did not differ by gender or age.

Discussion and conclusions

Many of the key results of this study—a low rate of service use, a large proportion of services delivered in school settings, and a relationship between diagnostic status and service use—are largely consistent with the findings of other recent studies of Indian and non-Indian adolescents. Given the considerable heterogeneity of Indian communities, such replication of findings is critical to understanding use of mental health and substance abuse services across these diverse communities until larger, multitribal studies are conducted.

The use of traditional healers was at least as common as the use of mental health specialists among the youths in this sample. This finding has not been previously reported in a community sample of Indian adolescents. It suggests that future studies of service use among Indian youths should carefully explore the use of traditional healers, the decision to seek such care, and the relationship between these factors and the use of biomedical services for mental and substance use disorders.

Another important finding of this study is that more than half of the youths who were found to have disorders and who had not used services reported that an adult had recognized their problem. Thus for many of these adolescents, the failure to obtain services was not simply because the need for care was not recognized. Future studies should explore relationships between problem recognition and availability, accessibility, and acceptability of mental health and substance abuse services. Such information will provide critical guidance for ongoing efforts to improve the delivery of these services to this underserved population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants R01-MH-42473 and K20-MH-01253 from the National Institute of Mental Health and from the Indian Health Service. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Monica Jones.

Dr. Novins, Dr. Beals, and Dr. Manson are with the National Center for American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research in the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Box A011-13, 4455 East 12th Avenue, Denver, Colorado 80220 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Sack is with the division of child psychiatry at Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland.

|

Table 1. Psychiatric status, service use, and problem recognition by an adult among 109 Northern Plains American Indian adolescents

1. Costello EJ, Farmer EMZ, Angold A, et al: Psychiatric disorders among American Indian and white youth in Appalachia: the Great Smoky Mountains study. American Journal of Public Health 87:827-832, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Indian Adolescent Mental Health. Washington, DC, US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, 1990Google Scholar

3. Verhulst FC, Van Der Ende J: Factors associated with child mental health service use in the community. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:901-909, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Beals J, Piasecki J, Manson SM, et al: Psychiatric disorder in a sample of American Indian adolescents: prevalence in Northern Plains youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:1252-1259, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Jensen P, Roper M, Fisher P, et al: Test-retest reliability of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC2.1): parent, child, and combined algorithms. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:61-71, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar