Satisfaction of Caregivers of Patients With Schizophrenia in Finland

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aims of the study were to determine whether the caregivers of discharged patients with schizophrenia were satisfied with their situation in general and with psychiatric services in particular and to examine the factors associated with caregiver satisfaction. METHODS: The data were drawn from a national project designed to study the treatment and life situation of deinstitutionalized schizophrenia patients in Finland. The patients were discharged from psychiatric hospitals in 1986, and both the patients (N=775) and their caregivers (N=545) were interviewed after a three-year follow-up. RESULTS: One-fifth of the caregivers were dissatisfied with the situation in general, and one-third were dissatisfied with the psychiatric services the patient received. Caregivers were more likely to be dissatisfied with the situation if they lived with the patient and if the patient's functional state was poor or the patient's use of services, particularly medication and rehabilitation, was low. Caregivers were likely to be dissatisfied with the psychiatric services if the patient had severe psychotic symptoms and poor "maintenance of grip on life" or if the patient was given less psychiatric care and rehabilitation or used more social services. CONCLUSIONS: The satisfaction of caregivers of persons with mental illness appears to have two dimensions. First, caregivers need to be accepted and treated as active partners in the patients' care and rehabilitation. Second, the burden on the families of persons with mental illness can be alleviated with long-term rehabilitation and care to help patients gain as high a functional state as possible.

Users' and caregivers' satisfaction with psychiatric services is used increasingly as a measure of outcome and quality of care (1). Interest in measuring consumer satisfaction with health services has increased substantially in the past two decades, but researchers have paid less attention to caregiver satisfaction.

Caregivers have been found to be more dissatisfied than patients, general practitioners, or social workers (2). Ruggeri and associates (3) found significant differences between patients and caregivers in their expectations of community psychiatric services, including a tendency to higher expectations among caregivers. Caregivers also have been reported to be more dissatisfied than patients with various dimensions of services. For example, they have complained about receiving insufficient information and inadequate practical advice from staff, especially on how to deal with further potential crises (4,5). Morgan (6) showed that satisfaction levels with emergency services in the United States were generally low among patients' families, who found it difficult to get help for their mentally ill family member in crisis situations. Patients' families appear to be particularly concerned with emotional resources, aftercare services, responses to requests for information, and greater participation in the patient's care (1,7,8).

Studies since the late 1980s have also reported more positive findings. Tessler and colleagues (9) reported that 53 to 73 percent of caregivers were satisfied with the outcome of contacts with mental health professionals, depending on the reason for the contact. Caregiver satisfaction varied significantly according to the different types of mental health professionals they had contact with. Respondents were the most satisfied with psychologists, followed by nurses, case managers, social workers, and psychiatrists (9). Biegel and coworkers (7) reported that two-thirds of the caregivers in their sample were satisfied with their contacts with professionals. Nevertheless, the caregivers ranked "more communications with professionals" as their greatest need.

Mira and associates (10) found that although the caregivers of severely ill patients saw therapists as competent, available, and polite, they found them lacking in skills for adequate communication with the patients and families. Solomon and Marcenko (11) found that caregivers were more satisfied with outpatient services than with inpatient services, and more satisfied with services provided to the patients than with those provided to themselves. Hatfield and colleagues (12) reported that caregivers rated hospitalization and office-based services more highly than community-based alternatives.

Grella and Grusky (13) found that the caregivers' background and family characteristics were negligible variables in explaining service satisfaction, although women were more often dissatisfied with the services. In general, parents were more satisfied than other caregivers. Family members' satisfaction with services was positively correlated with the time since onset of illness and, to a lesser extent, with the patient's age at onset of illness. However, the characteristics of the service system itself made the largest contribution to explaining family satisfaction, and the largest single factor was the case manager's role in providing emotional support to the families.

Caregivers' satisfaction with services may vary from country to country, but in general what seems especially to generate dissatisfaction is a lack of information, a low level of caregiver involvement, and poor efficacy of treatment (3,5,14,15,16,17).

Although researchers have made progress in their study of consumer satisfaction, little is known about the demographic, clinical, or service factors that might predict caregiver satisfaction with services. Our aims in this study were to determine whether the caregivers of discharged patients with schizophrenia were satisfied with their situation in general, and with the psychiatric services in particular, and to examine the factors associated with caregivers' satisfaction.

Methods

Sample

We drew data from a national project designed to study the treatment and the life situation of deinstitutionalized patients with schizophrenia in Finland. The project's dataset consists of patients between the ages of 15 and 64 with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who resided in 19 mental health or health care districts and who had been discharged from psychiatric hospitals.

Three separate samples were constructed for the project. From hospital discharge registers, patients consecutively discharged in three waves—after January 1, 1982, after January 1, 1986, and after January 1, 1990—were selected until the three samples amounted to 30 patients per 100,000 inhabitants in each district. Exceptions were one district in which the samples were half this size and another in which they were twice this size. The diagnoses for the 1982 and 1986 samples were based on ICD-8 criteria and those for the 1990 study on DSM-III-R criteria.

For this study we restricted our analysis to the 1,097 discharged patients in the 1986 sample, because only in this cohort were both patients and their caregivers interviewed at the three-year follow-up. Interviews were conducted successfully with 775 patients, or 71 percent of the sample. Forty patients, or 4 percent, declined to participate in the study interview but gave the researchers permission to use information collected during their previous visits to psychiatric hospitals or community mental health centers; for these patients the researchers answered the interview questions on the basis of this information. Another 137, or 12 percent, declined to participate in the study, although 78 of these patients gave permission for their caregiver to be interviewed. Ninety-six, or 9 percent, could not be located, and 49, or 4 percent, had died.

We noted no statistically significant differences in sociodemographic factors between the patients who took part in the follow-up study and those who did not. At the time of discharge, the overall level of functioning according to the 10-point version of the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) used in Finland (18) was poorer and the daily dose of neuroleptic drugs higher among the patients who were monitored in follow-up than among the dropouts. The follow-up group also had used psychiatric services to a greater extent before and particularly after discharge.

Our aim was to interview one caregiver for each patient. After excluding patients who had died (N=49), patients who could not be located (N=96), and patients for whom no one was close enough to qualify as a caregiver (N=39), we had a sample of 913 patients whose caregivers could be interviewed. Of these, 237 patients, or 26 percent, did not give permission to interview their caregivers, and 66 caregivers, or 7 percent, refused to be interviewed. Fifty-nine caregivers, or 6 percent, were not interviewed because the patients themselves had declined to participate in the study, and 6 caregivers were not interviewed for other reasons. Thus altogether 545 caregivers, or 60 percent, were interviewed.

The patients whose caregiver was interviewed were more often single than those whose caregivers were not interviewed, and their age at onset of illness was lower on average. At the time of discharge, the patients whose caregiver was interviewed were younger on average, had a lower functional status, were more often on disability pension, were more likely to use long-acting injection medication, and were more often discharged to live with their parents than those whose caregiver was not interviewed. During the three years following discharge, the patients whose caregiver was interviewed visited community mental health centers and used neuroleptic drugs and day hospital treatment more frequently than those whose caregiver was not interviewed.

Measures

Data were collected from psychiatric case records on the patients' psychiatric history and on their use of services during the three years before and after discharge. Data were also collected on the patients' overall level of functioning as measured by the 10-point GAS, somatic health, working ability, and medication at discharge. Three years after discharge the patients and their caregivers were interviewed separately by psychiatric teams using a structured interview schedule designed for this study. The patient interview included well-defined questions on the patient's psychosocial functioning; maintenance of grip on life (explained below); current living conditions; personal relationships; use of and need for psychiatric, medical, and social services, including a detailed list of various services and treatments; and the patient's satisfaction with the psychiatric care received. Data collection has been described in more detail elsewhere (19,20,21).

Maintenance of grip on life is a global assessment measure devised to evaluate treatment outcome for patients with schizophrenia (22). The concept of maintaining a grip on life is characterized by the patient's efforts to achieve the goals and modes of satisfaction normally associated with the interpersonal relationships and the social life of an adult.

The caregivers were interviewed using a modified version of the Medical Research Council Practices Profile (23). In this version, 19 structured items included questions about housework, self-care (hygiene, use of the toilet, eating, getting up, and going to bed), taking medicine, taking responsibility for one's own care, managing money, taking care of children, working, marital relationship, other interpersonal relationships, social contacts other than family, embarrassing behavior, social withdrawal, interest in events, activity, managing emergencies, and suicidal behavior. In each item, the caregiver was asked how much the patient required help and whether the caregiver was satisfied with the patient's behavior. The caregivers' satisfaction with the situation in general was measured on a 6-point scale, and their satisfaction with the psychiatric services was measured on a 3-point scale.

Statistical analysis

The differences between the proportions or the means were analyzed using chi square tests and t tests as appropriate. Logistic regression analysis (24) was used to select variables associated with two dependent variables—caregivers' dissatisfaction with the situation and with the psychiatric services. For the logistic regression the two scales measuring the caregivers' satisfaction were dichotomized, with 0 indicating satisfaction and 1 indicating dissatisfaction. As shown in Table 1, the independent variables for the analysis were initially organized into six groups: the patients' background, the caregivers' background, the patients' functional and clinical status, the patients' social relationships, the patients' need and use for services, and the patients' satisfaction with the care received.

The logistic regression analysis proceeded in two stages. First, each group of independent variables was entered separately into a backward stepwise logistic regression in which the probability criterion for removal was a p value greater than .1. In the second stage, the variables that remained in the models in the first stage (marked with L in Table 1) were entered into the final models, which are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. Because duration of illness as well as the patient's gender might interact with any other variable, these variables were forced into each model to control for their potential confounding effects.

Results

Caregivers' background. Two-thirds of the caregivers (N=359) interviewed were women. The mean±SD age of the caregivers was 56±14.6 years, with a range of 17 to 89 years. The caregivers of male patients were on average older than those of female patients (58.8 years versus 51.6 years; t=5.7, df=448, p<.001). Thirty-nine percent of the caregivers (N=211) were mothers of the patient, 10 percent were fathers (N=58), 5 percent were siblings (N=27), and 19 percent were spouses (N=103); 27 percent (N=146) were other caregivers or close friends.

Sixty percent of the caregivers (N=322) were not employed at the time of the study. About 38 percent (N=207) considered their health good. At the time of the interview 10 percent of the caregivers (N=52) were using psychiatric services themselves; another 12 percent (N=67) had used psychiatric services earlier. Half of the caregivers (N=274) lived with the patient they cared for, and about the same proportion of patients (N=284) spent most of their days at home.

Patients' background. The group of patients whose caregiver was interviewed consisted of 308 males (57 percent) and 236 females (43 percent). The mean±SD age was 37.3±10.6 years, with a range of 17 to 64 years. The majority of the patients were unmarried (70 percent, N=379) and on disability pension (86 percent, N=467). The patients' mean score on the 10-point GAS was 4.6±1.4, with a range of 1 to 9. The duration of illness was 12.7±8.7 years, ranging from less than a year to 39 years.

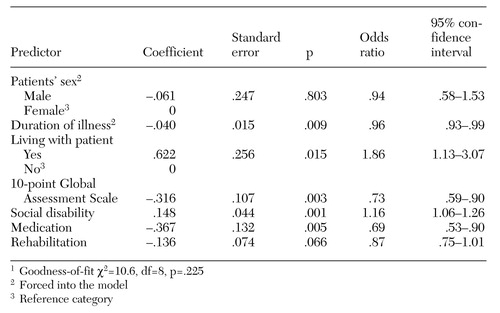

Caregivers' satisfaction with the situation. Twenty-two percent of the caregivers (N=119) were dissatisfied with the situation in general. As shown in Table 1, five of eight predictors of caregivers' satisfaction with the situation remained in the final logistic regression model: living with the patient, functional status, the patients' social disability, the medication given in the previous year, and the amount of rehabilitation at the time of the study. Table 2 summarizes the logistic regression equation with these variables as well as the two forced variables.

According to the logistic regression model, caregivers who lived with the patient (N=272) were more likely than those who did not (N=269) to be dissatisfied with the situation (26 percent versus 18 percent, respectively). Furthermore, caregivers whose patients had a lower functional status according to their GAS score or had more problems with social role behavior were more likely to be dissatisfied than those whose patients had better function and social capability. Caregivers also were more likely to be dissatisfied if the patients had been given less medication the year before and had undergone less rehabilitation at the time of the study.

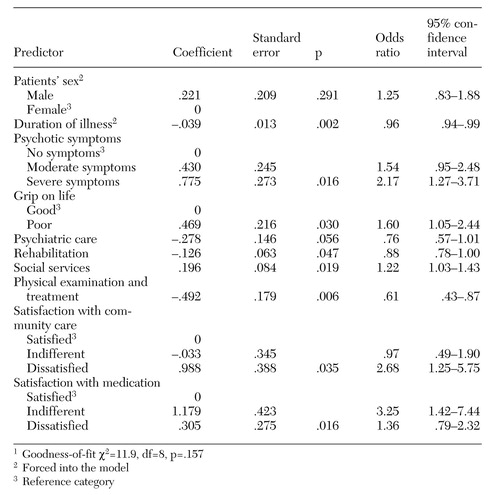

Caregivers' satisfaction with the services. Thirty-four percent of the caregivers (N=188) were dissatisfied with the psychiatric services the patients received. As shown in Table 1, eight of 13 predictors of the caregivers' satisfaction with the services remained in the final logistic regression model: patients' psychotic symptoms; maintenance of grip on life; psychiatric care, rehabilitation, and social services supplied at the time of the study; physical examination and treatment given in the previous year; and the patients' satisfaction with community care and medication. Table 3 summarizes the logistic regression equation with these variables as well as the two forced variables.

According to the logistic regression model, caregivers were more likely to be dissatisfied with the services if their patients had severe psychotic symptoms or poor maintenance of grip on life. Thirty-nine percent of the caregivers whose patients had psychotic symptoms (N=316) were dissatisfied, compared with 29 percent of those whose patients did not have psychotic symptoms (N=215). Forty-one percent of the caregivers whose patients had a poor maintenance of grip on life (N=269) were dissatisfied, compared with 28 percent of those whose patients had a good grip on life (N=264). Furthermore, caregivers whose patients were given less psychiatric care, rehabilitation, or physical examination and treatment were more likely than others to be dissatisfied. Caregivers whose patients had used more social services also were more likely than others to be dissatisfied.

Patients' attitudes toward the community care and medication they received were also associated with caregivers' level of satisfaction with services. Caregivers were more likely to be dissatisfied with services if the patients were dissatisfied with their community care or if the patients felt indifferent about their medication. Forty-seven percent of the caregivers whose patients were dissatisfied with community care (N=97) were dissatisfied with psychiatric services, compared with 31 percent of those whose patients were satisfied (N=402). Similarly, 48 percent of the caregivers whose patients were dissatisfied with their medication (N=119) were dissatisfied with services, compared with 31 percent of the caregivers whose patients were satisfied with their medication (N=395).

Discussion

This study was intended to identify factors associated with whether caregivers of patients with schizophrenia were satisfied or dissatisfied with the situation in general and with the psychiatric services the patient received. The sample consisted of caregivers whose mentally ill family members had been discharged from psychiatric hospitals and had been followed up for three years. Patients who remained in the program and were examined after three years were more severely disturbed and used psychiatric services more frequently than the program dropouts. Thus the caregivers who were interviewed constitute a sample of caregivers of severely disturbed, long-term patients with schizophrenia in Finland, which must be taken into account in evaluating the results of the study.

One-fifth of the caregivers were dissatisfied with the situation in general, and about one-third with the psychiatric services. Although previous studies have reported similar figures for caregiver dissatisfaction (5,17), research on caregiver satisfaction has been criticized for reporting implausibly high satisfaction scores with little variation (25). In this study the caregivers were interviewed by the psychiatric teams responsible for the care of the patients. As has been suggested in earlier studies (4,,26), the caregivers might have been reluctant to criticize the services on which they were so dependent.

Our analysis identified three main factors associated with caregiver dissatisfaction with the situation in general: patients' poor psychosocial functioning, patients' insufficient use of medication and rehabilitative services, and living with the patient. The patients' and caregivers' backgrounds and the patients' social relationships and satisfaction with their care had negligible roles in explaining the caregivers' dissatisfaction. This result may reflect the greater burden on caregivers taking care of patients with schizophrenia whose social role functioning is poor and whose needs for medication have not been adequately met. Caregivers living with the patient have been shown to perceive a greater burden and to have less satisfaction with their lives than caregivers who do not live with the patient (27,28).

Caregiver dissatisfaction with the services the patient received was associated with a set of factors different from those associated with their dissatisfaction with the situation in general. Caregivers were dissatisfied with services if the patients had severe psychotic symptoms or poor maintenance of grip on life and if they were given less psychiatric care, rehabilitation, and physical examination and treatment. The patients' use of social services and the patients' own dissatisfaction with community care and with their medication were also associated with caregiver dissatisfaction.

These findings suggest that the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia want rather basic things from psychiatric services. The most important factors in ensuring caregiver satisfaction seem to be rehabilitation measures that might improve patients' functional status and adequate medication, especially to control patients' psychotic symptoms. Patients with schizophrenia nevertheless also should be adequately examined and treated for physical illnesses.

The satisfaction of caregivers of mentally ill persons appears to have two dimensions. First, as previous studies have reported, caregivers need to be accepted and treated as active partners in patients' care and rehabilitation (4,5,7,8,15). Families want information about the illness and its treatment, and they want to know what they can do to help their sick family member. Second, the burden on the families of mentally ill people can be alleviated with long-term rehabilitation and care to help patients gain as high a functional state as possible. Social skills and basic skills in household work are especially important.

Conclusions

As other researchers have shown, caregiving is an important public health issue. Schene and colleagues (28) reported that caregivers suffering from distress also use significantly more psychotropic medications and consult their general practitioners more frequently. Dyck and associates (29) showed that positive symptoms in patients were predictive of infectious illness in caregivers. On the other hand, increased caregiver satisfaction with social support predicted a decreased frequency of episodes of infectious illness.

On the whole, the results of our study suggest that most caregivers of patients with schizophrenia are satisfied with their situation and with the psychiatric services in Finland. Nevertheless, 20 to 30 percent of caregivers—often those caring for patients with poor functional status and unmet needs in psychiatric care, rehabilitation, and medication—are dissatisfied. These caregivers need to be closely involved in the treatment process, and their needs for information, support, and counseling should be carefully assessed. Caregivers are capable of acting as a resource in the care of patients only if they receive sufficient support themselves.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the National Board of Health, the Association of Finnish Mental Hospitals, the League of Hospitals in Finland, and the Academy of Finland for their financial support.

Ms. Stengård and Ms. Koivisto are affiliated with the Tampere School of Public Health at the University of Tampere in Finland. Dr. Honkonen is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Helsinki and the psychiatric clinic at Helsinki University Central Hospital. Dr. Salokangas is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Turku. Send correspondence to Ms. Stengård at the Tampere School of Public Health, University of Tampere, FIN-33014, University of Tampere, Finland (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Independent variables for a logistic regression analysis of the satisfaction of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia with their situation in general and with psychiatric services

|

Table 2. Significant predictors from logistic regression analysis associated with dissatisfaction of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia with their situation in general1

1 Goodness-of-fit χ2=106, df=8, p=.225

|

Table 3. Significant predictors from logistic regression analysis associated with dissatisfaction of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia with psychiatric services1

1 Goodness-of-fit χ2=119, df=8, p=.157

1. Ruggeri M: Patients' and relatives' satisfaction with psychiatric services: the state of the art of its measurement. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 29:212-227, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. MacDonald LD, Ochera J, Leibowitz JA, et al: Community mental health services from the user's perspective: an evaluation of the Doddington Edward Wilson (DEW) mental health service. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 36:183-193, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ruggeri M, Dall'Agnola R, Agnostini C, et al: Acceptability, sensitivity, and content validity of the VECS and VSSS in measuring expectations and satisfaction in psychiatric patients and their relatives. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 29:265-276, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Leavey G, King M, Cole E, et al: First-onset psychotic illness: patients' and relatives' satisfaction with services. British Journal of Psychiatry 170:53-57, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wray SJ: Schizophrenia sufferers and their carers: a survey of understanding of the condition and its treatment, and of satisfaction with services. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 1:115-123, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Morgan SL: Families' experiences in psychiatric emergencies. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1265-1269, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Biegel DE, Song L, Milligan SE: A comparative analysis of family caregivers' perceived relationships with mental health professionals. Psychiatric Services 46:477-482, 1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Hanson JG, Rapp CA: Families' perceptions of community mental health programs for their relatives with a severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 28:181-197, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Tessler R, Gamacho G, Fisher G: Patterns of contact of patients' families with mental health professionals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:929-935, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Mira JJ, Fernández-Gilino E, Lorenzo S: Assessing the impact of mental health programs upon community: the perspectives of primary caregivers and consumers. International Journal for Quality Health Care 9(2):121-128, 1997Google Scholar

11. Solomon P, Marcenko M: Families of adults with severe mental illness: their satisfaction with inpatient and outpatient treatment. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:121-134, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Hatfield AB, Gearon JS, Coursey RD: Family members' ratings of the use and value of mental health services: results of a national NAMI survey. Psychiatric Services 47:825-831, 1996Link, Google Scholar

13. Grella CE, Grusky O: Families of the seriously mentally ill and their satisfaction with services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:831-835, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Merinder LB, Laugesen HD, Viuff AG, et al: Satisfaction with services in patients with schizophrenia and their relatives at two community mental health centres. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 53:297-303, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Gasque-Carter KO, Curlee MG: The educational needs of families of mentally ill adults: the South Carolina experience. Psychiatric Services 50:520-524, 1999Link, Google Scholar

16. Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, et al: Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: from treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services 50:233-238, 1999Link, Google Scholar

17. Salokangas RKR, Palo-Oja T, Ojanen M: The need for social support among outpatients suffering from functional psychosis. Psychological Medicine 21:209-217, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lönnqvist J: Evaluation of psychiatric treatment. Psychiatria Fennica 15:29-40, 1984Google Scholar

19. Stengård E, Saarinen S, Salokangas RKR: Skitsofreniapotilaan Selviytyminen Omaisen Näkökulmasta [Schizophrenia Patients' Social Adjustment Assessed by Their Relatives]. Report no 101. Helsinki, Psychiatria Fennican Julkaisusarja, 1993Google Scholar

20. Salokangas RKR, Saarinen S: Deinstitutionalization and schizophrenia in Finland: I. discharged patients and their care. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:457-467, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Honkonen T, Saarinen S, Salokangas RKR: Deinstitutionalization and schizophrenia in Finland: II. discharged patients and their psychosocial functioning. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:543-551, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Salokangas RKR, Räkköläinen V, Alanen YO: Maintenance of grip on life and goals of life: a valuable criterion for evaluating outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 80:187-193, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Creer C, Sturt E, Wykes T: The role of relatives, in Long-Term Community Care: Experiences in a London Borough. Edited by Wing JK. Psychological Medicine, suppl 2:29-39, 1982Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Fleiss JL, Williams JBW, Dubro AF: The logistic regression analysis of psychiatric data. Journal of Psychiatric Research 20:145-209, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Lebow J: Consumer satisfaction with mental health treatment. Psychological Bulletin 91:244-259, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Honkonen T: Need for care and support in schizophrenia. Dissertation. Acta Universitatis Tamperensis ser A, vol 437, 1995Google Scholar

27. Stengård E, Salokangas RKR: Well-being of the caregivers of the mentally ill. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 51:159-164, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Schene AH, van Wijngaarden B, Koeter MWJ: Family caregiving in schizophrenia: domains and distress. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:609-618, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Dyck DG, Short R, Vitaliano PP: Predictors of burden and infectious illness in schizophrenia caregivers. Psychosomatic Medicine 61:411-419, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar