Psychopathology and the Initiation of Disability Payments

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Longitudinal prospective data from the multisite Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) survey were examined to determine relationships between mental disorders, alcohol abuse or dependence, and transfer payments for disability. METHODS: ECA respondents who were not receiving disability benefits at baseline but who were receiving them at the one-year follow-up were identified. The effects of six psychiatric disorders on the risk of starting payments were examined. They were major depressive disorder, panic disorder, alcohol abuse or dependence, phobic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and schizophrenia. The odds of starting to receive payments were calculated for persons with these disorders, any mental or addictive disorder, or any two or more disorders, while the analysis controlled for sociodemographic characteristics. RESULTS: A total of 15,567 people were interviewed at baseline; 7 percent received disability payments. Among the 11,981 people interviewed at one year, 261 had begun to receive payments that year, for a starting rate of 2.2 percent. Significant predictors of the initiation of payments were little education (odds ratio=3.7) and low household income (OR=2.6). Respondents with panic disorder were 5.2 times more likely to begin receiving benefits than those without this disorder; respondents with schizophrenia were 4.5 times more likely and those with two or more disorders were 2.8 times more likely to start benefits than those without these disorders. CONCLUSIONS: Differences in social class influenced the initiation of disability payments. However, having a mental or addictive disorder was a more significant predictor, strongly increasing the risk of receiving payments. Given the economic burden to society and potential loss of earnings and opportunity costs for persons with disability and their families, intervening to prevent or alleviate mental disorders should be considered as one alternative to reducing disability payments.

The increase in numbers of beneficiaries of disability compensation since the late 1980s has brought renewed attention to persons with disabilities (1,2,3). Although age-specified mortality rates have dropped in the U.S., self-reported disability has increased in recent decades, particularly among working-age persons (4).

Employment rates for working-age persons with disabilities have decreased over the past three decades in the U.S. (5,6). More than 35 million Americans, or one in seven, have disabling conditions that interfere with their life activities (7,8,9,10). Although life expectancy has increased by four years since 1970, more than two years of that time is lost because of limitations on life activities. Disability has been called "the greatest public health problem in the U.S. today"(5) because it interferes with daily activities and limits functioning.

Social welfare benefit programs providing disability payments for mental illness have traditionally included Social Security, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Aid to Families With Dependent Children, Emergency Relief, and Veterans Disability Compensation. By 1991 about 1.2 million people were receiving either SSDI or SSI benefits as a result of a mental disorder (11). Persons with mental disorders represent the largest single diagnostic group of persons collecting benefits for disability— almost 22 percent of recipients.

Previous studies estimated associations of various measures of functioning with specific chronic medical conditions; few comparisons were made with patients experiencing distress or psychopathology (12). Depression may be related to disability because it is associated with nonpsychiatric medical conditions. Mental dysfunction is an important predictor of illness and physical disability among patients with chronic medical conditions (13). Associated depression is one of the most common secondary conditions, and it may produce additional impairment, functional limitation, and disability (14). Studies of psychopathology and work absences or "disability days" in the U.S. (15,16,17,18) and the U.K. (19,20) have demonstrated a significant association between levels of functioning and affective and anxiety disorders. The relative odds for developing a disability have been shown to be greater for persons with a psychiatric disorder or high distress than for those with any prior physical illness or those with a prior disability day (18).

Data on disability payments are difficult to obtain and to assess (21). Government program data are often aggregated, traced for only short periods, and include only beneficiaries with a recorded diagnosis; estimates of missing data range to 50 percent. Several factors preclude an accurate presentation of the nature and extent of disability, including the variety of data sources, the diverse definitions of disability (for example, mental disability with or without mental retardation, physical and mental disability, mental-physical disability, and physical-mental disability), and the frequent absence of statistical controls for sociodemographic differences such as sex or age (7,22). The absence of reliable and valid information on the incidence and prevalence of disability over time prevents an accurate assessment of the course of disability in relation to various risk factors or the impact of interventions on the development of disability. Little research has traced the evolution of psychopathology and disability in the general population.

The study reported here examined the association between disability payments— or payments for missing work or usual activities due to a disability— and a range of specific psychiatric disorders. Prospective longitudinal data from the multisite National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) survey permitted an examination of the relevance of changes in psychiatric disorders to the development of disability. We assessed and adjusted for the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on these relationships. Our data allowed us to measure disability on the basis of monetary transfers awarded by objective judges rather than retrospective recollections and self-assessments by subjects of their work absences (disability days) (15,16,17,18,19,20) or limitations on their activities (7,23,24,25). An analysis of population data on disability payments, types of disorders, and associated risk factors was conducted.

Methods

The ECA survey consists of community surveys conducted in five locations in the United States: Baltimore, Maryland; Durham, North Carolina; Los Angeles, California; New Haven, Connecticut; and St. Louis, Missouri. The ECA survey methods have been described elsewhere (26). The samples analyzed in the study reported here were drawn probabilistically from the household population aged 18 years or older in the five areas between 1980 and 1981. The St. Louis site was not included in our final analyses because of missing information on important control variables.

Subjects were interviewed in person at baseline and at follow-up one year later. Response rates for the initial interview at the four locations ranged from 68 to 79 percent. At the one-year interview, 20 percent were lost to follow-up; some were deceased (27).

Classifications of psychopathology were derived from DSM-III criteria (28). Diagnoses were made using the interview questions of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS), a semistructured interview designed for use by nonclinicians (29). Each participant in the survey underwent a 90-minute interview that included the DIS, which was scored to reflect DSM-III diagnoses (30) (diagnoses are referred to here as DIS/DSM-III disorders). At baseline and follow-up, symptoms experienced in the past year were counted only if they met the severity criteria of the DIS and were not explained by physical illness, use of medications, or alcohol or other drug use.

Unlike simple random sampling, in which respondents have equal probabilities of selection, the multistage sampling procedures of the ECA survey led to unequal probabilities of selection. Therefore, a weight was assigned to each respondent based on his or her selection probability, and weighted data were used in our analyses and are reported in the text and tables. The weighted procedure also adjusts variance estimates for the clustered aspect of the sampling so that tests of significance are conservative (27,31).

The dependent variable was ascertained by asking subjects at follow-up, "Are you receiving any disability payments or disability benefits from Social Security, the Veterans Administration, the state of [subject's state of residence], or from any other source?" Among the 11,981 people who were not receiving disability payments at baseline (the risk set), 261 were receiving payments at follow-up, yielding a starting rate of 2.2 percent.

Information on sociodemographic variables and psychiatric status was obtained from baseline interviews. For the follow-up cohort, psychiatric status was obtained from baseline or follow-up interviews. The sociodemographic variables included age, sex, race, education, household income, marital status, and number in household. Respondents who responded "black" when asked about their ethnic group were coded "black"; all others were coded "white or other." At follow-up, information about household income level (in dollars) was obtained for the past year.

Data analysis

As the number of beneficiaries was highly skew, analyses were performed using logistic regression with the presence or absence of disability payments as the dependent variable. In the first stage of the logistic regression, a multivariate sociodemographic model was created for disability payments. Variables were retained if the estimates were significant or if their inclusion substantially changed the magnitude of coefficients for other terms. In the second stage, psychiatric variables were added to the best-fitting sociodemographic model. There was one regression equation for each psychiatric disorder.

Respondents with one of the six psychiatric disorders, a summary variable representing odds for any mental or addictive disorder, or a summary variable representing odds for any two or more comorbid disorders were compared with respondents who did not have that DIS/DSM-III diagnosis. The analyses described below used multiple logistic regression procedures (32,33) to model the odds that an individual would start disability payments during the one-year follow-up. Both cross-sectional one-year analysis of the baseline cohort (N= 15,567) and follow-up analysis of the nonattritted cohort (N=11,981) are reported.

Results

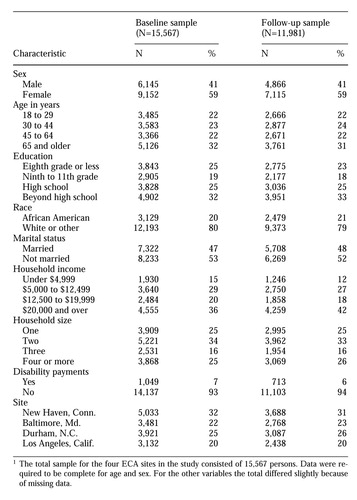

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the baseline and follow-up samples. A majority of the baseline cohort (59 percent) were female. Twenty percent of the baseline cohort were African American. At baseline, 7 percent of the respondents qualified for monetary assistance for a disability from the federal or state government.

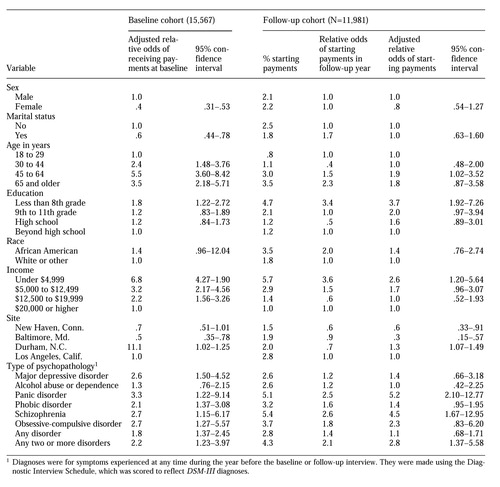

Table 2 presents data on predictors of disability payments, both at baseline and at follow-up. The effects of six psychiatric disorders on the risk of receiving disability payments were examined: major depressive disorder, panic disorder, alcohol abuse or dependence, phobic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and schizophrenia. Models examining a summary measure for any one of the above disorders and a summary measure of comorbidity, that is, having two or more disorders, were also created. Statistical adjustment in each equation included the sociodemographic variables.

As expected, at baseline respondents with low educational attainment were more likely (odds ratio=1.8) to receive disability payments than those with the highest level of education. Those with a low household income were more likely (OR=6.8) to receive payments than those with the highest income.

Age was also a significant predictor; respondents in the 45- to 64-year age group were almost six times more likely (OR=5.5) to receive disability payments than those in the youngest age group. Women in the baseline cohort were less likely (OR=.4) to receive payments than men, and married persons were less likely (OR= 0.6) to receive payments than those who were not married.

The introduction of psychiatric disorders in eight separate logistic regression equations demonstrated significant adjusted relative odds with baseline disability payments as the dependent variable. At baseline, persons with panic disorder were 3.3 times more likely than those without this disorder to receive disability payments. Persons with schizophrenia at baseline were almost three times more likely (OR=2.7) to receive payments than those without schizophrenia. Persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder were also nearly three times more likely (OR=2.7) to receive benefits than those without this disorder. Those with major depressive disorder were 2.6 times more likely to receive benefits than those without this disorder.

Subsequent analyses examined the initiation of disability payments in the follow-up period. As noted, payments were initiated for 261 persons (2.2 percent) in the cohort of 11,981 respondents interviewed at both baseline and follow-up. As shown in Table 2, significant predictors of starting new disability transfer payments ranged from less than 1 percent for the 18- to 29-year-olds to 5.7 percent for those in the lowest household income group. Respondents in New Haven had the lowest rates of disability payments (1.5 percent), while those in Los Angeles had the highest (2.8 percent). The unadjusted odds for starting disability payments differed trivially from the adjusted relative odds.

The strongest predictors of starting payments were low educational attainment (OR=3.7) and low household income (OR=2.6). Middle-aged persons (age 45 to 64) were almost twice as likely (OR=1.9) as younger persons to start to receive payments. Among the diagnostic groups, the highest rates for starting payments were for persons with schizophrenia (5.4 percent) and those with panic disorder (5.1 percent).

Logistic regression analysis for adjusted odds ratios in one regression equation was completed for the sociodemographic variables. Significant differences were found among the four communities surveyed; respondents from Baltimore had the lowest adjusted odds (OR=.3) of starting to receive assistance.

Phobia was the most common one-year-prevalence disorder at either interview; 1,815 respondents had a phobic disorder. More than 4 percent had more than one disorder. However, no single comorbid disorder exceeded 1 percent. Persons with major depressive disorder and a phobic disorder constituted the largest group of persons with a comorbid disorder (138 respondents, or 1 percent). Persons with phobia and alcohol use or dependence constituted the second largest group (82 respondents, or .5 percent), followed by those who had schizophrenia with depression (41 respondents, or .3 percent).

Table 2 shows the adjusted relative odds of starting to receive disability payments in the follow-up year for persons in the eight diagnostic groups. Inclusion of each psychiatric disorder in separate logistic regression equations demonstrated significant adjusted relative odds for a number of disorders. At follow-up, persons with panic disorder had the largest relative risk of starting payments; they were five times more likely (OR=5.2) to start payments than those without panic disorder in the nonattrited cohort.

Persons suffering from schizophrenia were 4.5 times more likely to start payments than those without this disorder. Those with major depression had a 40 percent greater relative risk (OR=1.4) of receiving new disability payments.

Comorbidity was also a significant predictor of starting disability payments. The risk for respondents with two or more psychiatric disorders was almost three times the risk (OR=2.8) for those without a comorbid disorder. Interactions of the model with the four ECA sites were introduced for each psychiatric disorder, but the results were not significant.

Discussion and conclusions

This study found that social class, as measured by income and education, was associated with the initiation of disability payments. However, race, sex, and marital status were not significant predictors of receiving payments. In prospective analyses, respondents with panic disorder were more than five times more likely and persons with schizophrenia were 4.5 times more likely to be disabled and receiving benefits than those without these disorders.

The finding that depression and panic disorders were significantly associated with receiving disability payments at baseline is consistent with data on work losses or disability days (17,18). We confirmed this association by measuring respondents' reports of actual monetary awards by government agencies rather than relying on recollections of respondents about their reasons for missing work or school or inability to perform activities.

We were able to control for physical illness and health insurance at only one site— Baltimore. In Baltimore, 204 of the 3,481 respondents (6 percent) were receiving disability benefits at baseline, and 54 respondents began receiving benefits during the follow-up year (2 percent). In the regression equation featuring the demographic characteristics shown in Table 1, the relative odds for physical illness or health insurance were not statistically significant or robust. Controlling by these two variables made the effect of psychopathology grow larger in almost every case, but the estimates were unstable because of the small sample size.

Annual disability-related costs in the United States for persons with mental disorders have doubled in the past ten years to approximately $23 billion; the number of beneficiaries has increased by 50 percent, from 4 million to 6.3 million Americans (34). We crudely estimated that our sample of 1,049 persons with a disability received about $9 million in economic transfers in 1981; this estimate does not include health care costs or benefits paid to spouses or dependents.

The increasing disability rolls may have resulted in the 1996 ruling by the Clinton Administration to eliminate federal entitlement to Aid to Families With Dependent Children, which provided disability benefits to children (35), and in recent federal legislation to eliminate persons from Social Security programs if their alcohol or drug addiction is the primary source of impairment (36). We found that persons with alcohol abuse or dependence were not more likely to receive disability payments. This finding may reflect the government's disinclination to qualify persons with alcohol or other drug disorders for economic benefits for a health disability (37).

Given the economic burden to society and potential earnings tradeoffs and opportunity costs for persons with disabilities and their families, efforts at reducing disability should be encouraged (38). Continuous employment, supportive services, and parity in pay and insurance for mental illness appear warranted (39,40,41). Many persons with mental illness or at risk for mental illness respond to preventive efforts or curative treatment. Clinical benefits from paid work activity have been demonstrated (42,43). Disability experienced by persons with psychopathology results in diminished quality of life, economic losses, and an increased need for health services. Efforts at prevention and treatment may result in a reduction in the number of persons in monetary compensation programs.

Acknowledgments

This analysis was supported by grant MH-47447 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Kung Yee-Liang, Ph.D., Fernando Wagner, Sc.D., and John Lawlor, M.H.S., for technical assistance and Margaret Ensminger, Ph.D., and Allen Y. Tien, M.D., M.H.S., for helpful comments.

Dr. Kouzis is assistant professor of ophthalmology and medicine in the School of Medicine and Dr. Eaton is professor in the department of mental hygiene in the School of Hygiene and Public Health at Johns Hopkins University, Wilmer 113, 600 North Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21287-9019 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey in the study sample at baseline and one-year follow-up1

1 The total sample for the four ECA sites in the study consisted of 15,567 personsData were required to be complete for age and sex. For the other variables the total differed slightly because of missing data.

|

Table 2. Predictors of receiveing disability payments at baseline and follow-up

1. Yelin E, Nevitt M, Epstein W: Toward an epidemiology of work disability. Milbank Quarterly 58:386-415, 1980Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Satel S: The politicization of public health. Wall Street Journal, Dec 12, 1996, p 12Google Scholar

3. Mechanic D: Cultural and organizational aspects of application of the Americans With Disabilities Act to persons with psychiatric disabilities. Milbank Quarterly 76:5-23, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wolfe BL, Haveman R: Trends in the prevalence of work disability from 1962 to 1984, and their correlates. Milbank Quarterly 68:53-80, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Johnson G, Baldwin M: The Americans With Disabilities Act: will it make a difference? Policy Studies Journal 21:775-788, 1993Google Scholar

6. Yelin E: Displaced concern: the social context of the work disability problem. Milbank Quarterly 67(suppl 2, part 1):114-166, 1989Google Scholar

7. Pope AM, Tarlow AR (eds). Disability in America: Toward a National Agenda for Prevention. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1991Google Scholar

8. LaPlante M, Carlson D: Disability in the United States: Prevalence and Causes, 1992: Disability Statistics Report 7. Washington, DC, US Department of Education, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, 1996Google Scholar

9. Disabled Americans: Self-Perceptions: Bringing Disabled Americans Into the Mainstream. New York, Harris & Associates, 1986Google Scholar

10. Elking J: The incidence of disabilities in the United States. Human Factors 32:397-405, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Kennedy C, Manderscheid RW: SSDI and SSI disability beneficiaries with mental disorders, in Mental Health, United States, 1992. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA. DUHS pub SMA 920-1942. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1992Google Scholar

12. Mintz, J, Mintz LI, Arruda MJ, et al: Treatment of depression and the functional capacity to work. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:761-768, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al: Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: results form the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 262:907-913, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Marge M: Health promotion for persons with disabilities: moving beyond rehabilitation. American Journal of Health Promotion 2:29-35, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Wells KB, Golding JM, Burnam NM: Psychiatric disorder and limitations in physical functioning in a sample of the Los Angeles general population. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:712-717, 1988Link, Google Scholar

16. Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LN, et al: Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 264:2524-2528, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kouzis AC, Eaton WW: Emotional disability days: prevalence and predictors. American Journal of Public Health 84:1304-1307, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Kouzis AC, Eaton WW: Psychopathology and the development of disability. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32:379-386, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

19. Jenkins R: Minor psychiatric morbidity in employed men and women and its contribution to sickness absence. British Journal of Industrial Medicine 42:147-154, 1985Medline, Google Scholar

20. Stansfeld S, Feeney A, Read J, et al: Sickness absence for psychiatric illness: the Whitehall study. Social Science and Medicine 40:189-197, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Okpatu SO, Sibulkin AE, Schenzler C: Disability determinants for adults with mental disorders: Social Security Administration vs independent judgments. American Journal of Public Health 84:1791-1795, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Shaar K, McCarthy M: Definitions and determinants of handicap in people with disabilities. Epidemiologic Reviews 16:228-242, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. National Research Council: Disability Statistics: An Assessment. Edited by Levine DB, Zitter M, Ingram L. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1990Google Scholar

24. Dunlop DD, Hughes SL, Manheim LM: Disability in activities of daily living: patterns of change and a hierarchy of disability. American Journal of Public Health 87:378-383, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. LaPlante MP: Disability in Basic Life Activities Across the Life Span: Disability Statistics Report I, 1989. San Francisco, University of California, Institute of Health and Aging, 1989Google Scholar

26. Eaton WW, Kessler LG (eds): Epidemiologic Field Methods in Psychiatry: The NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Orlando, Fla, Academic Press, 1985Google Scholar

27. Leaf P, McEvoy LT: Procedures used in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

28. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1980Google Scholar

29. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, et al: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:381-389, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Eaton WW, Holzer CE, Von Korff M, et al: The design of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:942-948, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Kessler LG, Felson R, Royall R, et al: Parameter and variance estimation, in Epidemiologic Field Methods in Psychiatry: The NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Orlando, Fla, Academic Press, 1985Google Scholar

32. Fleiss JL, Williams JB, Dubro AF: The logistic regression analysis of psychiatric data. Journal of Psychiatric Research 20:145-209, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Cleary PD, Angel R: The analysis of relationships involving dichotomous dependent variables. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 25:334-348, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Congress moving to slash SSI for mental illness. Psychiatric News, Mar 3, 1995, pp 1,22Google Scholar

35. Pear R:35,000 children to be struck from disability rolls. New York Times, Feb 7, 1997, p A25Google Scholar

36. PL 103-296, Apr 21, 1994Google Scholar

37. Rosenheck R, Frisman LK: Do public support payments encourage substance abuse? Health Affairs 15(3):192-200, 1996Google Scholar

38. Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, PL 101-336, sec 104, stat 327Google Scholar

39. Anthony WA, Jansen MA: Predicting the vocational capacity of the chronically mentally ill: research and policy implications. American Psychologist 39:537-544, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Marrone J, Balzell A, Gold M: Employment supports for people with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:707-711, 1995Link, Google Scholar

41. Racial Differences in Disability Decisions Warrants Further Investigation. GAO/ HRD 92-56. Washington, DC, General Accounting Office, 1992Google Scholar

42. Bell MD, Lysaker PH, Milstein RM: Clinical benefits of paid work activity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:51-67, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Scott CG: Disabled SSI recipients who work. Social Security Bulletin 55:26-36, 1992Medline, Google Scholar