County Behavioral Health Directors Cite Need for Changes in Community Care for Persons With Severe Mental Illness

Ninety percent of county officials responding to a recent survey by the National Association of County Behavioral Health Directors believe that community care of persons with serious and persistent mental illness needs to be changed. Forty-one percent identified the major problem as not having enough services for those in need, 37 percent as insufficient funding, 10 percent as the stigma associated with mental illness, and 9 percent as not enough housing.

The findings were based on 351 telephone interviews conducted between December 1999 and January 2000 in the first national survey of county behavioral health directors. County agencies headed by the respondents serve an average of 2,120 individuals with severe mental illness each year. The survey, funded by Eli Lilly and Company, was designed to identify policy priorities for public-sector behavioral health authorities in the wake of concerns about the quality of services raised by the Surgeon General's report on mental health.

Eighty percent of the directors gave highest priority to the need to improve public understanding of serious and persistent mental illness. Other priorities were the need to improve rehabilitative support (67 percent), to improve coordination between agencies (67 percent), and to increase unrestricted access to pharmaceutical therapy (65 percent).

The majority of respondents indicated that the newer drugs have been beneficial for many patients. Eighty-two percent noted improvement in medication compliance rates, and 65 percent said hospitalization rates were lower. Seventy-eight percent said patients taking the newer drugs were more likely to take advantage of education, employment, and other services, and 81 percent said they were more likely to succeed in meeting their goals.

One respondent in five indicated that the state or county imposes restrictions on access to the newer drugs, and six out of ten believe that the restrictions have affected their ability to provide effective care. The most frequent restriction was a financial cap on the pharmacy benefit, identified by 42 percent of respondents, followed by limits on the total number of drugs dispensed in any month (9 percent), a requirement that the patient must fail to improve on two conventional antipsychotics before using the newer drugs (7 percent), and a requirement for failure on one drug (5 percent). Two percent said patients in their counties could not use the newer drugs at all.

Seventy-one percent of the county agencies offer supported education programs for persons with serious and persistent mental illness, and another 5 percent had plans to do so. However, 60 percent of the respondents rated their county's supported education programs as fair or poor.

Seventy-five percent of the respondents said their agency offered supported employment services, which served an average of 75 persons within the past year. Another 5 percent planned to offer such services. Forty-two percent of participants in existing employment programs found jobs, mostly lower-level positions, which predominated among the jobs developed by the county agency. Fifty-seven percent of the respondents rated the quality of employment support programs in their communities as only fair or poor.

Asked about barriers to work for persons with serious mental illness, 70 percent of the respondents cited lack of transportation as a critical stumbling block. However, 64 percent identified lack of public awareness or tolerance. Other barriers identified were client symptoms, 54 percent; fear of loss of Social Security benefits, 48 percent; lack of suitable jobs, 48 percent; and lack of education, 42 percent.

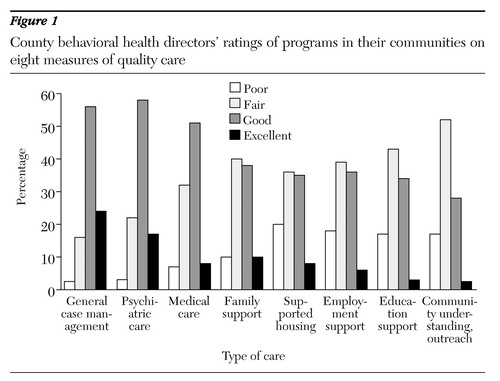

The respondents also were asked to rate their county programs on eight measures of quality care. General case management got the highest ratings; 24 percent rated it excellent and 56 percent good. Ratings on all eight measures are shown in Figure 1.

The National Association of County Behavioral Health Directors, an affiliate of the National Association of Counties, has 300 organizational members in 22 states. For more information about the survey, contact the association at 1555 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036; phone, 202-234-7543; fax, 202-462-9043.

Report Criticizes State Policies Requiring Parents to Give Up Custody of Children to Receive Mental Health Services

In half of the states in the U.S. nearly one in four families face the "inhumane choice" of giving up custody of their child to obtain mental health treatment for the child or retaining custody and forgoing treatment, according to a report for the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law.

The report, entitled Relinquishing Custody: The Tragic Result of Failure to Meet Children's Mental Health Needs, says parents face such a dilemma because of limits on health care coverage and misinterpretation of federal laws by state agencies. It asserts that no state agency should require parents to relinquish custody before providing mental health services to a child.

No federal law currently entitles all children to mental health services regardless of family income, and there is no single source of state or federal funding for these services, the report points out. Instead, children must gain access to services from several uncoordinated and poorly implemented entitlement programs.

Medicaid-eligible children are entitled to all mental health services necessary to treat or ameliorate health needs identified by screening. But states' implementation of this entitlement is erratic, the report says. Children's mental health needs often are not identified, and in some states residential treatment providers refuse to serve Medicaid-eligible children unless they are wards of the state.

The federal Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP) provides funds for states to offer health insurance to children in families with incomes above the Medicaid eligibility level, but often these state-sponsored plans do not provide intensive mental health services, the report says. Many children are ineligible for Medicaid or CHIP because of family income. Some have insurance through a parent's employer, but typically these plans limit mental health services by restricting hospital days and outpatient visits.

Some children receive mental health services through the federal special education law, the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which guarantees all children a free and appropriate education, including services needed to benefit from education. But the report says that many school districts interpret this provision too narrowly, to exclude mental health services that enable a child to attend school.

The report says that erroneous interpretation of the federal Foster Care and Adoption Assistant Program creates a fiscal incentive for relinquishing custody by reimbursing some of the costs of care when children are removed from their parents' home. Many state officials and judges mistakenly assume that the child welfare system must have custody of a child to access the federal funds.

The report recommends that the state act to prohibit custody relinquishment for access to mental health services and also to address the underlying cause, the lack of mental health services. The recommendations call for enforcing federal entitlements under the IDEA and Medicaid, expanding children's eligibility for Medicaid, and creating a system of care for children with mental health needs.

Several federal and state initiatives are steps in the right direction, the report indicates. Two Medicaid programs allow states to expand Medicaid coverage for children who would require hospital care but could appropriately receive home- and community-based services or services in nonhospital settings, provided that the alternative care costs the same as or less than hospital care.

Some states have acted to increase access to services without obtaining custody, the report says. Eleven states prohibit the child welfare agency from requiring parents to relinquish custody to receive mental health services for their child. Seven states allow voluntary agreements between parents and the child welfare system for out-of-home placement without the parents' relinquishing custody.

States are also changing their administrative policies to more fully implement the requirement to provide all medically necessary services to children, even if the services are optional, the report notes. Twenty-one states and two territories have expanded their Medicaid programs under CHIP, and 13 states have a combination of state-designed and Medicaid CHIP programs.

Some states are working to implement the IDEA entitlement to educational and related services, which has no income-eligibility criteria. They are also broadening their definition of serious emotional disturbance and thus expanding the number of children eligible for mental health services.

States are also developing comprehensive mental health services for children and families. Seven states have enacted legislation to combine funding from various agencies that serve children in comprehensive systems of care.

The report is available for $10 plus $4 for shipping and handling from the Publications Desk, Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, 1101 15th Street, N.W., Suite 1212, Washington, D.C. 20005. It can also be ordered from the bookstore on the Bazelon Center's Web site, www.bazelon.org.

Consensus Report Calls for More Research on Child Anxiety Disorders

Research on psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for childhood anxiety disorders lags far behind research on other childhood disorders, according to a report developed by a national consensus conference. The meeting of experts on child and adolescent disorders was convened by the Anxiety Disorders Association of America and sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health. The report, which formulates an action plan for future research, was published in February.

The report, entitled Treating Anxiety Disorders in Youth: Current Problems and Future Solutions, cites recent estimates suggesting that about 10 percent of all children experience anxiety disorders at some time. Childhood anxiety disorders include separation anxiety disorder; panic disorder; phobias, such as social phobia, agoraphobia, and specific phobias; obsessive-compulsive disorder; posttraumatic stress disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Although the 10 percent prevalence rate is similar to that of other childhood disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety disorders receive far less attention from researchers and the media, the report notes. One reason may be the perception that fears in children are common and transient. Although some fearful reactions may be temporary, the report points out that anxiety disorders can be differentiated by the intensity of the symptoms and the effects on daily functioning. Without timely intervention, childhood anxiety disorders can lead to depression and substance abuse in adolescence and young adulthood, according to research cited by the report.

The consensus conference focused on three areas—diagnosis and classification, treatment, and prevention. The report includes an overview of the complex task of developing a valid and reliable diagnostic classification scheme for childhood anxiety disorders. Comorbidity is a particular problem in understanding and classifying childhood anxiety, according to the report. In some samples, up to 80 percent of youths have comorbid anxiety and other internalizing disorders, such as depression. The report notes that a number of children experience excessive worries and somatic symptoms that are not captured by the current diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder. In addition, the report calls for the development and use of indicators of impairment that adequately address all aspects of childhood functioning, including academic, social, and familial.

The authors of the report hope especially to draw attention to the lack of research on pharmacological and psychosocial interventions. Fewer than 20 controlled trials of either type of intervention for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders have been published. The report recommends starting treatment with cognitive-behavioral therapy, except in the case of severe illness or suicidality. Cognitive-behavioral therapy has considerably more empirical support than pharmacotherapy for childhood anxiety, the report notes, and in combination with medication, it may be the treatment most likely to lead to durable symptom remission. The report further emphasizes that interventions should be expanded from a sole focus on the child to other contextual factors important in the child's environment. Such interventions would target family, school, and community systems.

Although pharmacologic treatments are increasingly recognized as an essential part of treatment for anxious youth, the exact place of medications, alone and in combination with psychosocial interventions, is not clear, largely because of the lack of controlled trials. An exception is pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder, for which there are robust data to show the efficacy of clomipramine and some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), according to the report. For other anxiety disorders, the report recommends use of high-potency benzodiazepines as appropriate short-term treatments for a broad range of anticipatory and situation-related anxiety symptoms. Until further studies are completed, SSRIs are probably the agents of choice for long-term treatment, the report notes.

The report also calls for research on strategies to prevent the onset of childhood anxiety disorders. An important aspect of such research will be identifying high-risk youth and understanding the factors that increase or decrease children's vulnerability to these disorders.

The full text of the report is available on the Web site of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America at www.adaa.org.

News Brief

Consensus statement on children's services: A coalition of eight organizations led by the American Academy of Pediatrics has drafted a consensus statement on insurance coverage of mental health and substance abuse services for children and adolescents. The consensus statement makes a series of recommendations related to access, coordination, and monitoring of care, including parity in insurance coverage for mental health and substance abuse services, increased involvement of families in the coordination of care, and expansion of the number of clinicians qualified to treat youths with mental health and substance use disorders. Other organizations in the coalition were the Academy for Eating Disorders, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, Family Voices, the International Society of Psychiatric- Mental Health Nurses, and the Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. For more information, contact Jane Edgerton at the American Psychiatric Association; phone, 202-682-6857; fax, 202-842-5844; e-mail, [email protected].

Figure 1. County behavioral health directors' ratings of programin their communities on eight measures of qualitycare