Use of Nursing Homes in the Care of Persons With Severe Mental Illness: 1985 to 1995

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined patterns of care for persons with mental illness in nursing homes in the United States from 1985 to 1995. During that period resident populations in public mental hospitals declined, and legislation aimed at diverting psychiatric patients from nursing homes was enacted. METHODS: Estimates of the number of current residents with a mental illness diagnosis and those with a severe mental illness were derived from the 1985 and 1995 National Nursing Home Surveys and the 1987 and 1996 Medical Expenditure Surveys. Trends by age group and changes in the mentally ill population over this period were assessed. RESULTS: The number of nursing home residents diagnosed with dementia-related illnesses and depressive illnesses increased, but the number with schizophrenia-related diagnoses declined. The most substantial declines occurred among residents under age 65; more than 60 percent fewer had any primary psychiatric diagnosis or severe mental illness. CONCLUSIONS: These findings suggest a reduced role for nursing homes in caring for persons with severe mental illness, especially those who are young and do not have comorbid physical conditions. Overall, it appears that nursing homes play a relatively minor role in the present system of mental health services for all but elderly persons with dementia.

When public mental hospitals began reducing their resident populations in 1955—a trend that accelerated between 1965 and 1975—many patients were transferred to nursing homes and other residential institutions (1,2,3,4). The Medicaid program encouraged states to make such shifts by reimbursing nursing home care but not care in public mental hospitals. In its important 1986 study, the Institute of Medicine noted that the number of persons with mental illnesses residing in nursing homes could be attributed, in part, to "the massive discharges from state hospitals during the 1970s" (1). During that period, according to the study report, "The number of elderly persons in mental hospitals decreased about 40 percent, while the mentally ill in nursing homes increased by over 100 percent."

Following the Institute of Medicine study and other reports of poor quality care in nursing homes, Congress enacted the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA-87), which included provisions meant to improve care. The act mandated preadmission screening to ensure that only residents in need of nursing care be admitted to nursing homes, that yearly reviews of problems and services be conducted for each client, and that facilities provide active mental health treatment to patients with a primary mental illness (5). This requirement was expected to reduce the use of the nursing home for clients with mental illnesses (6,7), although dementia-related conditions continued to qualify for nursing home admission.

Since OBRA-87 was passed, however, the reduction of resident patients in mental hospitals has continued. In previous analyses we estimated that bed days in such hospitals were reduced by 12.5 million between 1988 and 1994 (8). Although nursing homes may no longer be the "dumping ground" for the mentally ill that they were in earlier years, we know little about the extent to which they continue to be used (9). Using the 1977 National Nursing Home Survey (NNHS), Goldman and associates (10) estimated that 668,000 residents had chronic mental illness or dementia. However, only 72,000 residents had a mental illness but no complicating physical or dementia-related condition. These patients, whom the authors refer to as "purely" mentally ill, should probably be cared for elsewhere. Goldman and associates also estimated that only about 5,500 residents under age 45 had a mental illness as their primary problem. Eichmann and colleagues (6) estimated that in 1985 approximately 18 percent of nursing home residents did not meet the criteria of admission under OBRA-87. They suggested that the legislation would have a profound effect on the case mix of residents in nursing homes.

In a recent review of studies that assessed the effects of OBRA-87, Snowden and Roy-Byrne (11) called for further research to examine the impact of this legislation. In this study, we used data from two national surveys conducted before and after the enactment of OBRA-87 to examine three issues: change in number of mentally ill residents in nursing homes, change in the diagnostic case mix of persons with mental illness, and change in level of need for nursing care among such residents.

Methods

The first surveys from which we used data were the 1985 and 1995 National Nursing Home Surveys (NNHS), conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. The surveys used a two-stage stratified sampling design in which a nationally representative sample of licensed and nonlicensed facilities with at least three beds was selected, and then a random sample of residents and staff in these facilities was selected. The 1985 sample included 1,079 homes and 5,238 current residents, and the 1995 survey included 1,409 homes and 8,056 residents. Detailed methodological information has been published elsewhere (12,13).

Current diagnoses in the NNHS are coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) (14). As many as eight diagnoses were recorded in 1985, but we included only the first six to correspond with the coding used in 1995. We defined mental illness as ICD-9-CM codes between 290 and 319. We analyzed separately the prevalence of schizophrenia and related disorders (codes 295 and 297 to 299), depression (262.2, 296.3, 298.0, 300.4, and 311), dementia-related disorders (293, 294, and 310), and other disorders (the remaining psychiatric codes) separately.

We further analyzed a subgroup we defined as having a severe mental illness, a category that included schizophrenia and related diagnoses, bipolar disorder (codes 296.0 and 296.1, 296.4 to 296.9), obsessive-compulsive disorder (300.3), and major depressive disorder with psychotic features (296.34 and 296.24). These diagnoses, the most severe and complex mental illnesses, have been linked to persistent and prolonged social and psychosocial impairment (15,16,17,18,19).

Although we do not assume that these diagnoses include all persons with severe mental illnesses, the group does include those who tend to have more severe psychopathology. In some analyses, we excluded residents with dementia-related disorders or Alzheimer's disease (code 331) from our classification of mental disorders because they are eligible for nursing home care under OBRA-87. Similarly, we excluded residents with diagnoses of mental retardation (codes 318 and 319) because we believe they represent a subgroup of patients who require separate study. Diagnoses were missing for 129 sampled residents in 1985 and 13 residents in 1995; these cases were excluded from the analyses.

We also used these data to examine the prevalence of physical comorbidity and level of dependency in activities of daily living (ADL), such as bathing, eating, dressing, transferring, walking, toileting, or difficulty controlling bowels or bladder, all of which are proxies for need for nursing care.

Medical Expenditure Survey

In addition to the NNHS data, we used data from the institutional component of the Medical Expenditure Survey (MES) collected in 1987 and the nursing home component of the panel survey collected in 1996 by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. The MES surveys include information about facilities and a representative sample of current residents on the first day of each year. In the first sampling stage, facilities were selected that had at least three beds certified by Medicare or Medicaid or were licensed nursing homes providing registered nursing or licensed practical nursing care. In the second stage, current residents from these homes were randomly sampled. Further details of the study designs are provided elsewhere (20,21).

In 1987 a total of 810 homes were selected with a sample of 3,347 persons who were residents; comparable numbers in the first round of the 1996 survey were 952 and 3,747. Information about the residents' health was either abstracted from medical records or collected from a staff member.

In the MES, the interviewer asked a knowledgeable staff member to review the resident's record and indicate the presence of several "active" illnesses, defined as "diagnoses or conditions associated with ADL status, cognition, behavior, medical treatments, or risk of death." In 1986 the conditions listed included depression, dementia or organic brain disease, anxiety, schizophrenia, other psychoses, personality and character disorders, mental retardation, autism, or any other mental disorders.

The 1996 MES listed schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, dementia or organic brain disorder, and anxiety as mental disorders and provided space to record other active conditions. Other conditions were recoded and put in appropriate categories. Because of the broader definition of mental disorder, we anticipated higher estimates of mental illness in the MES than in the NNHS, but to the extent that both surveys yield consistent patterns, they validate each other.

Statistical issues

For both surveys, the standard errors used for tests of significance had to be adjusted to account for the complex survey designs. The coefficients provided by NCHS were used to calculate relative standard errors in the NNHS data (12,13). Sudaan software (22) was used in the analyses of the MES data to adjust standard errors appropriately. All estimates presented were weighted to be nationally representative.

Results

Data from the NNHS indicated that almost 67,000 residents (4.5 percent) in nursing homes had been admitted from mental health facilities in 1985, but the number fell to less than 27,000 (1.8 percent) in 1995, a statistically significant drop (z=6.3, p<.05). This is a sizable change, but it may in part reflect survey format changes. In 1985 the survey specified facilities such as psychiatric units of general hospitals, state hospitals, and mental health centers; the 1995 survey included only "mental health facility" as a category. Thus transfers from specialized units of general hospitals in 1995 may not have consistently been coded as transfers from mental health facilities.

As expected, because of its more expansive definition, the MES estimated a larger number of persons with any listed mental illness than the NNHS—more than a million in 1996 compared with about 900,000 in 1995 in the NNHS. Mental illness diagnoses were more often assigned in the mid-1990s than they were ten years earlier, increasing by about 14 percent in the NNHS and 8 percent in the MES.

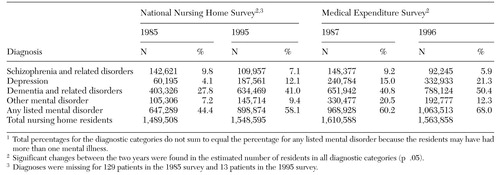

As Table 1 shows, both surveys indicated that the number of residents with a current diagnosis of schizophrenia and related disorders significantly declined. In contrast, the number of residents with depressive disorders and disorders related to dementia significantly increased, but with larger variation between the two surveys.

The pattern for other mental disorders was inconsistent between the two surveys and probably reflects the different methods for listing disorders. For example, using MES data, 42 percent of persons in the "other" category were identified as having character disorder, an imprecise diagnosis not included in the 1996 survey. This inconsistency probably accounts for the very substantial drop in other mental disorders reported in the MES over time.

To understand the increase in the prevalence of depression, we focused on the NNHS because it has more complete diagnostic information. These results (not shown in the table) indicate that depression was a primary diagnosis for less than 2 percent of residents and that the number of such residents increased only marginally over time from 1.4 percent of the total resident population to 1.7 percent. Moreover, the increase was observed only in the population over age 65, where we found that approximately 7,500 more residents had a primary diagnosis of depression in 1995 than were found in 1985. Thus the increase in depressive diagnoses appears overwhelmingly to be an increase in secondary, not primary, illness.

To explore changes that may have been influenced by OBRA-87 more fully, we assessed the prevalence of mental illness, excluding residents with a primary or secondary dementia-related condition or mental retardation. The NNHS indicated that the number of residents in nursing homes with a primary mental illness diagnosis significantly decreased from approximately 101,000 in 1985 to 70,000 in 1995. The decline is largely explained by the substantial reduction of such residents who were under age 65 (63 percent).

An even larger reduction occurred for primary diagnoses of severe mental illness, with statistically significant reductions in the number of residents in both age groups, those under 65 and 65 years and older. In 1995 there were about 12,000 severely mentally ill persons under age 65 without dementia, almost two-thirds fewer than in 1985. Approximately 29,500 persons age 65 and over had a severe mental illness, a decline of about 17 percent since 1985. Although the numbers become small and unreliable with further age stratification, the drop in severely mentally ill residents is inversely related to age, with the largest drop among persons under age 55, more moderate decreases among residents between 55 and 64, and the smallest reductions among those 65 and older.

To assess need for nursing care, we examined the prevalence of physical comorbidities and differences in level of dependencies in activities of daily living. Over time, the number of residents with a primary diagnosis of mental illness (excluding dementia) with no comorbidity declined substantially over time; in 1985 a total of 45 percent of such residents did not have a comorbid physical illness, whereas in 1995 only 17 percent had no comorbid condition. A similar pattern emerged for residents with a primary severe mental illness. We estimated that by 1995 fewer than 8,000 severely mentally ill residents with no physical comorbidity were in nursing homes, an approximate four-fifths reduction from 1985.

A more direct assessment of level of disability involves examination of the number of dependencies experienced by residents in 1985 compared with 1995. Residents experiencing three or more problems in activities of daily living increased from 73 percent in 1985 to 79 percent in 1995. The most substantial change, however, occurred among residents with a primary mental illness (excluding dementia); in 1985 about a third of these residents had three or more dependencies, whereas in 1995 approximately half experienced this level of dependency.

These analyses also point to the importance of separating dementia-related illnesses from other mental illnesses when considering the number of mentally ill residents in nursing homes who might be eligible for care in less restrictive settings. Persons with dementia-related illness, as either a primary or a secondary diagnosis, have more dependency problems than those with other forms of mental illness.

Discussion and conclusions

In this paper we address the issue of whether nursing homes continue to be a dumping ground for persons with serious mental illness as the number of residents in public mental hospitals has continued to decline. We have shown that the number of persons in nursing homes with mental health diagnoses has increased between 1985 and 1995, but most of these clients have dementia-related conditions. Such data have been the basis of claims that a majority of persons in nursing homes have a mental illness and help explain estimates of almost a million mentally ill people in these institutions.

Using the data from the two surveys, we could justify estimates ranging from less than 8,000 to more than a million. These estimates are meaningless without further subclassification, since the clinical and social policies required to deal with dementias, depression, and schizophrenia—with and without comorbidities—are quite different. Approaches to caring for young patients with serious mental illness and no comorbidity are also entirely different from strategies for caring for aged persons with a severe mental illness and significant physical problems. The estimates commonly bandied about do not serve us well.

Nursing homes have traditionally been the last refuge in our society for those who cannot be maintained in community settings because of physical and behavioral problems, the lack of caretakers, or insufficient community services that include long-term care. Although judgments can be made about eligibility for nursing home admission, no clear criteria exist for making such judgments. Admission is typically seen as appropriate when a person experiences many limitations in daily activities or when, because of dementia, he or she causes disturbances, wanders, is incontinent, or generally becomes exceedingly difficult for community caregivers to manage. Loss of caretakers among those with significant activities of daily living dependencies also often triggers nursing home admission.

Most of the nursing home residents with diagnoses of mental illness are older and suffer from dementias. Depression typically is a secondary diagnosis. Differentiating primary from secondary conditions is often difficult, however, and dementia may appear exaggerated in some patients because of depressive illnesses. If appropriate treatment were provided for such patients, some might function better and be able to avoid institutionalization. Survey studies such as those reported here cannot speak to this important issue, but this is clearly an area that needs intensive clinical research.

Nevertheless, our analyses suggest an improving picture of the changing role of nursing home care for persons with serious mental illness and the likely effects of OBRA-87 regulations on nursing home admission patterns and performance. Any attribution of change specifically to the act has to be circumspect, since many other changes in health policy have occurred over the ten-year period. It appears, however, that following the passage of OBRA-87 the number of severely and persistently mentally ill persons in nursing homes substantially declined, and there are now many fewer such residents. This change is particularly pronounced among younger residents and may suggest a trend in the direction of the preferred pattern. However, these data do not tell us whether persons with severe mental illnesses, who may have previously been treated in nursing homes, are now being treated in more appropriate alternative residential settings that provide the range of services they require.

Whether persons with mental illness and no dementia or physical comorbidities are being inappropriately placed in nursing homes is a social policy issue that needs to be considered. We estimate that this problem is relatively small, involving less than 12,000 residents, many of whom also do not have serious limitations in their activities of daily living that might require nursing care. This estimate compares with 1.8 million discharges of adults with a primary psychiatric diagnoses from general hospitals in 1995 (573,000 with a diagnosis of severe mental illness) (unpublished data, Mechanic and McAlpine, 1999) and approximately 700,000 discharges from mental hospitals in 1994 (8). The nursing home thus fulfils a relatively minor role in the present system of mental health services for all but elderly persons with dementia. However, this is not to suggest that attention need not be focused on such important issues as the appropriate treatment of depression before and during nursing home residency, the proper use of psychotropic drugs, and the monitoring of the use of restraints.

Although the two surveys used in these analyses provide the best national nursing home data available, they have significant limitations. Some of the changes we observed, such as the increase in diagnoses with dementia-related conditions and depression, may reflect changes in diagnostic coding after OBRA-87 rather than changes in the population. Legal and regulatory changes may encourage diagnostic judgment consistent with nursing home admission and Medicaid reimbursement. Information on the use of psychotropic drugs would be helpful but is not available in these surveys. Finally, although the nursing home may not be used as a mental health facility in most places, such practices may be more common in specific localities, a possibility that cannot be examined with these national data.

Acknowledgment

This paper was done as part of Healthcare for Communities: The Alcohol, Drug, and Mental Illness Tracking Study, a collaborative effort funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The authors are affiliated with the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research, 30 College Avenue, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901-1293. Address correspondence to Dr. Mechanic (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Nursing home residents with a diagnosis of mental illness in the National Nursing Home Survey and the Medical Expenditure Survey1

1. Committee on Nursing Home Regulation, Institute of Medicine: Improving the Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1986Google Scholar

2. Carling PJ: Nursing homes and chronic mental patients: a second opinion. Schizophrenia Bulletin 7:574-579, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kruzich JM: The chronically mentally ill in nursing homes: issues in policy and practice. Health and Social Work 11:5-14, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Schmidt LJ, Reinhardt AM, Kane RL, et al: The mentally ill in nursing homes: new back wards in the community. Archives of General Psychiatry 34:687-691, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987, Public Law No 100-203, Title V, Subtitle C, sections 4201-4206, 4211-4216Google Scholar

6. Eichmann MA, Griffin BP, Lyons JS, et al: An estimation of the impact of OBRA-87 on nursing home care in the United States. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:781-789, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Freiman MP, Arons BS, Goldman HH, et al: Nursing home reform and the mentally ill. Health Affairs 9(4):47-60, 1990Google Scholar

8. Mechanic D, McAlpine DD, Olfson M: Changing patterns of psychiatric inpatient care in the United States:1988-1994. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:785-791, 1998Google Scholar

9. Anderson RL, Lewis DA: Clinical characteristics and service use of persons with mental illness living in an intermediate care facility. Psychiatric Services 50:1341-1345, 1999Link, Google Scholar

10. Goldman H, Feder J, Scanlon W: Chronic mental patients in nursing homes: reexamining data from the national nursing home survey. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:269-272, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Snowden M, Roy-Byrne P: Mental illness and nursing home reform: OBRA-87 ten years later. Psychiatric Services 49:229-333, 1998Link, Google Scholar

12. National Nursing Home Survey, 1985, computer file, 4th release. Hyattsville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics, 1991. Distributed by Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor, Mich, 1992Google Scholar

13. 1995 National Nursing Home Survey, Description of the NNHS on 1995 National Nursing Home Survey, CD-ROM, series 13, no 9. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, June 1997Google Scholar

14. Public Health Service and Health Care Financing Administration: International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. Washington, DC, Public Health Service, 1980Google Scholar

15. Harrow M, Sands JR, Silverstein ML, et al: Course and outcome for schizophrenia versus other psychotic patients: a longitudinal study. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:287-303, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Goldberg JF, Harrow M, Grossman LS: Recurrent affective syndromes in bipolar and unipolar disorders at follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry 166:382-385, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Koran LM, Thienemann ML, Davenport R: Quality of life for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:783-788, 1996Link, Google Scholar

18. Coryell W, Leon A, Winokur G, et al: Importance of psychotic features to long-term course in major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:483-489, 1996Link, Google Scholar

19. McKay AP, Tarbuck AF, Shapleske J, et al: Neuropsychological function in manic-depressive psychosis: evidence for persistent deficits in patients with chronic, severe illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 167:51-57, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research: Round 1, facility-level public use file codebook, in Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) NHS-001: Round 1 Sampled Facility and Person Characteristics, March 1997. CD-ROM. AHCPR pub 97-DP21. Rockville, Md, AHCPR, 1997.Google Scholar

21. Edwards W, Edwards E: Questionnaires and data collection methods for the institutional population component. National Medical Expenditure Survey Methods 1. National Center for Health Services Research and Health Care Technology Assessment. DHHS pub PHS 90-3470. Rockville, Md, Public Health Service, September, 1990Google Scholar

22. Shah BV, Barnwell B, Bieler GS: Sudaan User's Manual, Release 7.0. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1996Google Scholar