Lessons From a Comprehensive Clinical Audit of Users of Psychiatric Services Who Committed Suicide

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Characteristics of patients who committed suicide were examined to provide a picture of the treatment they received before death and to determine whether and how the suicides could have been prevented by the service system. METHODS: The unnatural-deaths register was matched to the psychiatric case register in the state of Victoria in Australia to identify suicides by people with a history of public-sector psychiatric service use who committed suicide between July 1, 1989, and June 30, 1994. Data on patient and treatment characteristics were examined by three experienced clinicians, who made judgments about whether the suicide could have been prevented had the service system responded differently. Quantitative and qualitative data were descriptively analyzed. RESULTS: A total of 629 psychiatric patients who had committed suicide were identified. Seventy-two percent of the patients were male, 62 percent were under 40 years old, and 51 percent were unmarried. They had a range of disorders, with the most common being schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (36 percent). Sixty-seven percent had previously attempted suicide. A total of 311 patients (49 percent) received care within four weeks of death. Twenty percent of the suicides were considered preventable. Key factors associated with preventability were poor staff-patient relationships, incomplete assessments, poor assessment and treatment of depression and psychological problems, and poor continuity of care. CONCLUSIONS: Opportunities exist for the psychiatric service system to alter practices at several levels and thereby reduce patient suicides.

The risk of suicide is higher among psychiatric patients than among the general population (1,2). Many studies of patient-based risk factors for suicide have been published (2,3), but less is known about treatment-based risk factors (4).

An audit was conducted to improve the management of suicide risk among patients of the public psychiatric service system in the Australian state of Victoria. Its aim was to describe the characteristics and treatment of public-sector psychiatric patients who committed suicide and to determine whether the service system could have prevented some of the suicides.

Methods

In August 1995 the government of Victoria commissioned us to undertake the audit. Victoria has well-developed public and private health sectors that provide general and specialist mental health care to a population of approximately 4.5 million. We were given ministerial exemption to gain access to confidential clinical records. We identified all suicides that occurred in Victoria between July 1, 1989, and June 30, 1994, from the Victorian Department of Justice's unnatural-deaths register, which records all investigations by the coroner into sudden and unexpected deaths. All deaths deemed suicides by the coroner were included in the audit.

We matched the unnatural-deaths register to the Victorian psychiatric case register (5,6) to identify suicides by people with a history of public-sector psychiatric service use. The Victorian psychiatric case register is a person-based register that records individuals' contacts with all Victorian public inpatient and community psychiatric services. Unique identifiers allow tracking of individuals across services.

When the study was carried out, paper-based clinical records followed the patient. Thus the service that had provided the most recent care also provided consolidated clinical files representing each person's total history of public psychiatric service use in Victoria.

Three experienced clinician-auditors were trained to use a pen-and-paper instrument designed for the study to extract certain information from each clinical record: the patient's demographic characteristics; symptoms, including suicide risk; clinical presentation and principal diagnosis; clinical history, including previous suicide attempts; social history; and inpatient and community treatment. A diagnosis was assigned through a schema of ICD-10 clinical terms, collapsed into five diagnostic clusters.

Each auditor judged whether the suicide could have been prevented by an alternative response of the service system, and each auditor provided reasons for this judgment. Efforts to ensure consistency in the auditors' judgments included a glossary of definitions and regular meetings to discuss decisions. (Copies of the audit instrument and glossary are available from the authors.)

The auditors' quantitative responses were analyzed using SPSS (7) and Stata (8) statistical software. Their qualitative responses were subjected to content analysis using the NUD*IST program (9).

Results

The study identified 2,638 suicides in Victoria over the five-year period. A total of 629 suicides (24 percent) were by people who had a history of contact with Victorian public psychiatric services; 452 (17 percent) had received public-sector care during the previous 12 months, and 311 (12 percent) had done so within four weeks of death.

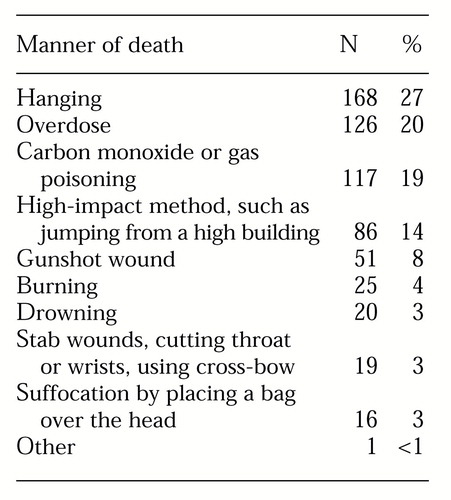

As Table 1 shows, most deaths were by hanging (27 percent), overdose (20 percent), or carbon monoxide or gas poisoning (19 percent).

Patient characteristics

The patients who committed suicide were predominantly male and relatively young. A total of 454 of the 629 patients were male (72 percent). Three hundred of the males (66 percent) and 89 of the females (51 percent) were under 40 years old. Many of the patients (303, or 51 percent) were unmarried, and 173 patients (28 percent) were socially isolated at death. Social isolation was defined as "not in regular contact with friends, if any, or family, if any."

A diagnosis was available for 599 of the 629 patients. Of these, 215 (36 percent) had schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 123 (21 percent) had manic-depressive psychosis or major depression, 119 (20 percent) had neurotic depression, and 142 (24 percent) had other nonpsychotic or personality disorders.

A total of 418 patients (66 percent) had made at least one previous suicide attempt. One hundred forty-eight patients (24 percent) had made one previous attempt, 98 (16 percent) had made two, and 172 (27 percent) had made three or more.

Many patients had a pathological family history. A total of 371 patients (59 percent) had a history of childhood problems. Such problems included parental separation; severe parental conflict; a chaotic family life; living with others for significant periods of time; foster care; neglect; a critical-hostile or cold-distant relationship with parents; parental alcoholism, psychiatric illness, physical illness, or drug abuse; and other trauma. A total of 236 (36 percent) had a family history of psychiatric illness, and 86 (14 percent) had a family history of suicide. Such family histories were common across diagnostic clusters.

Of the 629 patients, 114 (33 percent) had a history of violence to others or to property, and 163 (26 percent) had been involved with the justice system, including court appearances, significant police involvement, forensic psychiatric treatment, and involvement with a youth training center. A total of 307 (49 percent) had a history of drug or alcohol abuse.

Treatment characteristics

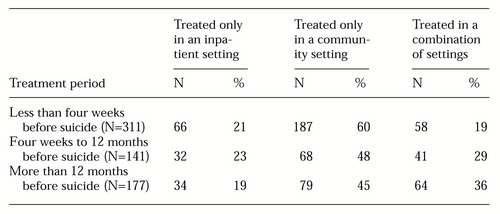

As shown in Table 2, of the 311 patients who received care within four weeks of suicide, 66 (21 percent) were treated exclusively in inpatient settings, 187 (60 percent) were treated exclusively in community settings, and 58 (19 percent) were treated in both settings. Forty-six patients (7 percent of the total) were inpatients at the time of death—13 resided in an inpatient facility, 18 were on leave, and 15 had absconded. This pattern was similar for patients with more than four weeks between last treatment and death, although there was a tendency for more of them to have received both types of care and fewer to have received community care only.

Judgments of preventability

The auditors believed that 125 of the suicides (20 percent) could have been prevented had the service system responded differently. The auditors cited several factors in their judgments.

Assessment factors. In terms of assessment factors, judgments of preventability were most commonly associated with suboptimal staff-patient relationships (in 78 cases, or 62 percent).

The auditors cited poor or incomplete assessment of suicide risk in 74 cases (59 percent), concluding that the patient's suicide risk was not adequately ascertained or its level not given due weight.

The auditors also cited poor assessment of symptoms that were not specific criteria for the patient's diagnosis. For example, affective symptoms were sometimes overlooked in the absence of a diagnosis of an affective disorder. Poor assessment of depression or psychological issues was among the reasons for judgments of preventability for 19 of the 45 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder whose suicides were considered preventable (42 percent). Poor assessment of depressive symptoms was cited in the case of four of the 20 patients with other nonpsychotic or personality disorders whose suicides were judged preventable (20 percent).

Also associated with judgments of preventability were poor assessment of current functioning (14 patients, or 11 percent) and poor history taking (13 patients, or 10 percent).

Cross-setting treatment issues. For 30 suicides judged to be preventable (24 percent), the auditors noted that no documented counseling for psychological problems occurred, or, if it did, it was inadequate. The auditors also cited inadequate treatment of depression (20 cases, or 16 percent).

Inpatient treatment issues. In the case of 24 preventable suicides (19 percent), the auditors cited poor quality of the inpatient staff-patient relationship as a reason for their judgment.

Other inpatient treatment issues cited were poor communication between inpatient staff (15 cases, or 12 percent), inappropriate discharge (12 cases, or 10 percent), and insufficient planning or action regarding leave (11 cases, or 9 percent).

Community-based treatment issues. A judgment of preventability was sometimes based at least partly on the auditors' perception that the response to suicide risk by a community team was inadequate. In 19 of the cases (15 percent), the inadequate response occurred when patient care was the responsibility of a continuing care team. The auditors cited excessive time between appointments with a continuing care team for 16 preventable suicides (13 percent).

The auditors based their judgments of preventability on poor relationships between the patient and a continuing care team in 14 cases (11 percent) or a crisis assessment and treatment team in six cases (5 percent). For six preventable suicides (7 percent), the auditors based their judgment on a reduction in or change of medication.

Continuity-of-care issues. Twenty-nine of the preventable suicides (23 percent) were attributed, at least partly, to continuity-of-care issues, because the patient was not admitted to an inpatient unit, the patient was refused admission, or admission could not be arranged. In 11 of the preventable cases (9 percent), the auditors stated that the patient was refused services or offered limited services by a continuing care team. Refusal or abrupt termination of services by a crisis assessment and treatment team was given as a reason in 38 cases (30 percent).

In 25 preventable suicides (20 percent), the judgment was based on the fact that the patient appeared to need but did not receive assertive community follow-up.

Poor transition between services was also cited. Twenty of the preventable suicides (16 percent) were attributed to poor transition at least in part because the patient had been poorly transferred or discharged from a community mental health center.

The loss of or change in case manager was given as a reason in 15 cases (12 percent), presumably where termination issues and the transition to a new case manager were not dealt with adequately.

Discussion

Audit context

The audit reported here was undertaken as an exercise in quality assurance on the principle that mental health care can be improved by reviewing past practice. The audit involved judgments and opinions about the quality of care from experienced mental health professionals. We believe that the only recent comparable work is the National Confidential Inquiry Into Suicide and Homicide by People With Mental Illness carried out in the United Kingdom by Appleby and associates (4).

Our audit differed somewhat from the British audit in that the Victorian psychiatric register facilitated identification of psychiatric suicides, and we had a consolidated clinical file representing the patient's entire history of service use from which three clinician-auditors extracted information. Appleby and colleagues examined details of each suicide that were submitted to the main hospital providing psychiatric services in the person's health district. Only persons who had been patients in the 12-month period before death were identified as cases. The treating psychiatrist and mental health team were identified and asked to contribute information about relevant care.

In our audit, 17 percent of all suicides were by people who had received public-sector psychiatric care during the previous 12 months. This estimate is lower than the 24 percent estimated by Appleby and colleagues. The Victoria and United Kingdom service systems differ, with the former defining services more narrowly. The Victoria system serves only persons with serious mental illness and not those with intellectual disability or substance abuse problems (10). The United Kingdom system also had a significantly larger private sector, which sees some patients who in Victoria would be seen in the public sector. Accordingly, the British study may have included cases that our audit excluded.

Patients who committed suicide in Victoria were predominantly male, relatively young, and unmarried. Most commonly, they had schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Relatively high proportions had childhood problems and a family history of psychiatric illness or suicide. This finding was true for all diagnostic groups, including those with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, whose suicides are often attributed to an insight into the illness rather than family pathology. A history of drug or alcohol abuse, forensic involvement, and violence to others or to property were common in our audit. Typically, patients were socially isolated. Many had made previous suicide attempts. In general, this profile is consistent with that found in the study by Appleby and colleagues (4), whose psychiatric suicides had "broad social and clinical needs."

Almost half of the people in our audit who committed suicide had been treated within four weeks of their death, which is consistent with findings from a number of other studies (11). Appleby and associates (4) reported a similar figure (50 percent) for a one-week period. Again, this finding may reflect differences in service delivery systems.

In our audit, of those treated within four weeks of suicide, about a fifth were inpatients, three-fifths were community patients, and a fifth had received treatment from both service elements. Seven percent were formal inpatients at the time of death. This figure compares with 16 percent found by Appleby and associates. Again, different service delivery frameworks may explain this discrepancy.

Comparison points

We can place these findings in context by considering data on two relevant groups treated during the same period: people in the general population who committed suicide and people who used public psychiatric services, bearing in mind that psychiatric suicides form a subset of both groups.

According to general population reports of suicide in Victoria in 1995 (12), males were slightly underrepresented among the psychiatric suicides. Approximately 78 percent of all suicides in the general population were by males, compared with 72 percent of psychiatric suicides. Young people were overrepresented among the psychiatric suicides. Twenty-nine percent of suicides in the male general population were by persons under 40 years old, compared with 66 percent of male psychiatric suicides. The corresponding figures for females were 42 percent and 51 percent.

The Victorian coroner's data from 1991 to 1996 (12) suggest that the methods used by psychiatric suicides generally mirror those of suicides in the general population. However, overdoses were somewhat more common among psychiatric suicides, accounting for 20 percent of all suicides among this group, compared with 15 percent in the general population.

When the demographic information on psychiatric suicides was compared with data on all psychiatric patients from 1991 and 1992 (13), males were overrepresented among psychiatric suicides. Psychiatric patients as a total group constituted approximately equal numbers of males and females. Likewise, young people were overrepresented among the psychiatric suicides—57 percent of all male psychiatric patients and 42 percent of all female psychiatric patients were under 40 years old.

By extrapolating from 1992-1993 data (14), it was possible to estimate the breakdown by diagnostic group of all psychiatric patients. During that year, approximately 47 percent of all patients were diagnosed as having schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 21 percent had manic-depressive psychosis or major depression, 11 percent had neurotic depression, and 21 percent had other nonpsychotic or personality disorders. In this context, those with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were underrepresented among the psychiatric suicides (36 percent), and those with neurotic depression were overrepresented (20 percent).

Treatment setting data from 1992-1993 showed that 6 percent of all psychiatric patients were treated in the inpatient setting only, 71 percent in community settings only, and 22 percent in both (14). Direct comparisons with the psychiatric suicides described here are complicated by the fact that their treatment setting data were broken down by the most recent treatment period, but it is apparent that patients who were categorized as psychiatric suicides were more likely to have received treatment in the inpatient setting than their counterparts who did not commit suicide.

Perceptions of preventability

The auditors judged that 20 percent of the psychiatric suicides could have been prevented had the service system responded differently. The mental health teams in the study by Appleby and associates (4) judged a similar proportion of suicides to have been preventable—22 percent.

A key factor influencing judgments of preventability was poor staff-patient relationships. Suboptimal relationships created difficulties with assessment and treatment in both inpatient and community settings. This finding is perhaps not surprising, given the nature of the cohort—patients who eventually commit suicide are often challenging. As noted, many are isolated, and this isolation can be associated with limited social skills or inappropriate behavior, such as aggression. In combination, these characteristics can engender negative feelings among clinicians, leading in turn to a lack of sympathy and support (15). The mutuality of clinician-patient relationships, and their impact on appropriate assessment and treatment, needs to be acknowledged. Silverman and colleagues (16) discussed this issue and stressed the importance of a solid therapeutic relationship in establishing a suicide contract.

The auditors in our study often cited poor or incomplete assessments as a reason for judging suicides to have been preventable. Either the suicide risk was not adequately ascertained or the level of risk was not given due weight. This is a common failure scenario in outpatient practice and in the inpatient setting (16,17). In our audit, inadequate assessment occurred in different ways for different diagnostic groups. For example, among patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, it often occurred in the context of a focus on psychotic symptoms that hampered the clinician's ability to consider the patient's current stresses. For those with other nonpsychotic or personality disorders, it was often associated with the poor staff-patient relationships noted above, which resulted in encounters in which clinicians gave insufficient consideration to the patient as a whole person. Clinicians may experience time pressures and may feel that they lack enough training and support to deal with patients at risk of suicide. Difficulties in managing suicide risk may mean that some clinicians avoid identifying the risk.

Another issue noted by the auditors was poor treatment, particularly of depression and psychological problems. Poor treatment often occurred when the focus of attention was on addressing other symptoms more directly related to the diagnosis, such as hallucinations and delusions in patients with schizophrenia. This finding highlights the fact that assessing and treating those likely to commit suicide involves developing a full understanding of the patient. Clinicians should be supported in detecting, diagnosing, assessing, and treating conditions such as depression, especially when they occur as comorbid conditions (18). Clinicians may want to consult others to ensure that they provide appropriately tailored interventions (16).

Several factors associated with poor continuity of care were also among the key reasons given for judgments of preventability. Bongar and associates (17) noted the importance of carefully managing transitions, such as changes in therapist, because transitions are a time when the patient may be particularly vulnerable. Silverman and coworkers (16) discussed the importance of planning for discharge from the inpatient setting to the community.

Changing trends in public psychiatric service delivery in Victoria during the time of the audit might have been expected to have an impact on continuity of care. On the one hand, moves toward more integrated service systems would be expected to improve linkages between individual service elements. On the other hand, the changes have led to caseloads that include more patients with serious mental illness. For most public psychiatric services, this means more patients with schizophrenia or mood disorders and severe symptoms. Consequently other patients, such as those with personality disorders, are given lower priority. These factors, and a demand that could not be fully met, may explain why some patients whose cases were examined in the audit were refused services or inadequately followed up.

Tackling the problem

Policy makers have suggested that psychiatric services can help achieve reductions in suicide rates (19). Our findings suggest that these services cannot do it all, given that only a fifth of those who committed suicide were in contact with such services in the 12 months before their death. However, our findings also indicate that suicide prevention by such services can be improved.

To improve suicide prevention, it is necessary to take a systems-level approach at four levels.

• Policy makers and funders have responsibility for articulating the policy framework and ensuring that funding systems provide additional resources for complex cases and for staff development.

• Managers of psychiatric services have responsibility for ensuring that at-risk patients receive optimal care by promoting relevant guidelines and providing opportunities for regular supervision and debriefing.

• Academic institutions and professional bodies have responsibility for reviewing their curricula to ensure that they incorporate issues associated with dealing with at-risk patients, including assessing and managing suicide risk.

• Clinicians have responsibility for ensuring that they assess and assertively treat and manage at-risk patients appropriately. This task involves adhering to guidelines, continuously undertaking self-review, and seeking assistance when "stretched to the limit."

These recommendations have been made to the Victorian Department of Human Services, which is committed to their implementation.

It was beyond the audit's scope to investigate instances in which the service system successfully responded to prevent suicides. Anecdotally, we know that such instances are common. Here we have documented cases in which the system did not respond adequately, aiming to learn from these experiences. We believe there are opportunities for the psychiatric service system to change its practices and thereby reduce suicides among its patients.

Acknowledgments

Conrad Hauser, M.A., M.A.P.S., Andrew McKenzie, R.N., and Jane Morton, M.A., M.A.P.S., were the auditors in this study. Norman James, M.D., F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., provided input into the design and conduct of the audit. Adam Clarke, B.Sc. (Hons.), Simon Palmer, B.Comm., M.A., and Shayne Loft, B.A. (Hons.), undertook database development, data management, and analysis. Paul Mullen, M.S., F.R.C.Psych., Bill Buckingham, B.Sc. (Hons.), Dip.Clin.Psych., and Deanna Clancy, M.A., M.A.P.S., offered valuable comments on the presentation of material. Sophia Kalogiannis provided administrative support. The mental health branch of what was at the time of the study the Victorian Department of Health and Community Services funded the audit.

Dr. Burgess is head of the policy and analysis group and Ms. Morton is consultant clinical psychologist at the Mental Health Research Institute, 155 Oak Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Pirkis is a senior research fellow at the Centre for Health Program Evaluation of the University of Melbourne at West Heidelberg, Victoria. Ms. Croke is senior clinical adviser in the office of the chief psychiatrist of the mental health branch of the Victorian Department of Human Services in Melbourne, Victoria. Dr. Burgess is also associate professor in the department of psychological medicine at Monash University in Clayton, Victoria.

|

Table 1. Manner of death of 629 persons who had received public-sector psychiatric treatment in Victoria, Australia, and who committed suicide

|

Table 2. Most recent period during which 629 persons who committed suicide received public-sector psychiatric treatment, by treatment setting

1. Harris CE, Barraclough B: Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry 170:205-228, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Tanney BL: Mental disorders, psychiatric patients, and suicide, in Assessment and Prediction of Suicide. Edited by Maris RW, Berman AL, Maltsberger JT, et al. New York, Guilford, 1992Google Scholar

3. Roy A, Draper R: Suicide among psychiatric hospital inpatients. Psychological Medicine 25:199-202, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Appleby L, Shaw J, Amos T, et al: Suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services: national clinical survey. British Medical Journal 318:1235-1239, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Burgess PM, Joyce CM, Pattison PE, et al: Social indicators and the prediction of psychiatric inpatient service utilisation. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 27:83-94, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Sytema S, Burgess P: Continuity of care and readmission in two service systems: a comparative Victorian and Groningen case-register study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 100:212-219, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 8.0. Chicago, SPSS, 1998Google Scholar

8. Stata Statistical Software, version 6.0. College Station, Tex, Stata, 1997Google Scholar

9. QSR NUD*IST, version 4.0. Melbourne, Australia, Scolari, 1997Google Scholar

10. Psychiatric Services Division, Health and Community Services: The Framework for Service Delivery. Melbourne, Victorian Government, 1994Google Scholar

11. Pirkis J, Burgess P: Suicide and recency of health care contacts: a systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry 173:462-474, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Suicide Prevention: Victorian Task Force Report. Melbourne, Victorian Government, 1997Google Scholar

13. Victorian Department of Health and Community Services: Victoria's Health Reforms: Psychiatric Services: Discussion Paper. Melbourne, Victorian Government, 1993Google Scholar

14. Victorian Department of Health and Community Services: Annual Report, 1993-94. Melbourne, Victorian Government, 1994Google Scholar

15. Watts D, Morgan G: Malignant alienation. British Journal of Psychiatry 164:11-15, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Silverman MM, Berman AL, Bongar B, et al: Inpatient standards of care and the suicidal patient: II. an integration with clinical risk management, in Risk Management With Suicidal Patients. Edited by Bongar B, Berman AL, Maris RW, et al. New York, Guilford, 1998Google Scholar

17. Bongar B, Maris RW, Berman AL, et al: Outpatient standards of care and the suicidal patient, ibidGoogle Scholar

18. Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT: Risk factors for serious suicide attempts among youths aged 13 through 24 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:1174-1182, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health: Better Health Outcomes for Australians: National Goals, Targets, and Strategies for Better Health Outcomes Into the Next Century. Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia, 1993Google Scholar