Datapoints: Mental Health Parity and Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance in 1999-2000: I. Limits

The late 1990s witnessed a wave of state and federal mandates that require private insurance to cover behavioral health care at the same levels as general medical care. Typical employer-sponsored mental health plans in the 1990s imposed several limits, often including visit or day limits in addition to dollar limits, as well as higher deductibles, copayments, or coinsurance rates than for general medical care (1,2). The most problematic differences in insurance benefits are limits in coverage because plans with limits partially insure individuals against smaller expenses but leave them at full risk for high expenses that exceed the limit. In fact, limits protect the insurer against high costs, not the individual.

Although patient advocacy groups have hailed the passage of numerous parity laws, the scope of legislation was narrower than many realized. The federal bill requires parity only in dollar limits, not in visit or day limits or copayments, and some of the stronger state bills do not apply to many employer-sponsored plans. We examined whether mental health benefits have changed markedly since parity legislation was enacted. We analyzed preliminary data from the employer survey in the Health Care for Communities study (3), including responses from July 1999 through July 2000. Data for earlier years were obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (1).

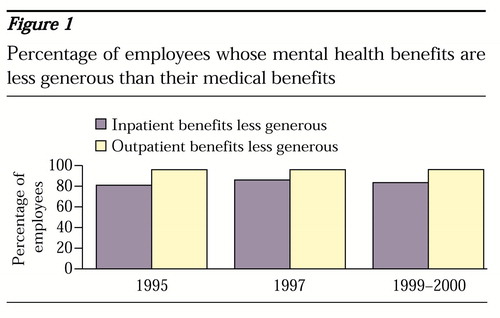

Figure 1 shows changes over time in the number of employees whose mental health benefits—including limits, copayments, and deductibles—are less generous than their medical benefits. Despite numerous parity bills since 1998, there have been virtually no changes. The main difference is that limits in 1995 and 1997 were split between dollar and day or visit limits (data not shown), whereas in 1999-2000 all limits were day or visit limits. We did not assess dollar limits in 1999-2000 because of the federal legislation.

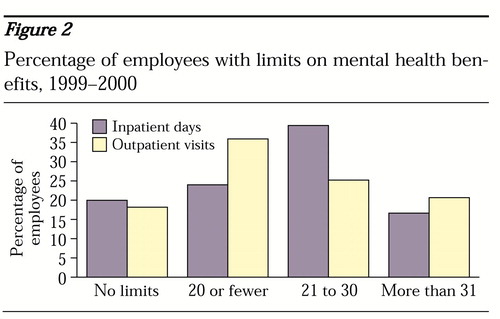

Figure 2 presents data on the most problematic benefit design difference, namely limits, and provides more detail on annual day limits for inpatient care and visit limits for outpatient care. According to preliminary national data for 1999-2000, only about one in five individuals with employer-sponsored mental health insurance have no day or visit limits. In addition, limits on coverage are very low. More than half of all plan members are covered for 20 or fewer outpatient visits, and about 60 percent are covered for 30 or fewer inpatient days.

Acknowledgment

The Health Care for Communities study was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The authors are affiliated with Rand, 1700 Main Street, Santa Monica, California 90401 (e-mail, [email protected]). Harold Alan Pincus, M.D., and Terri L. Tanielian, M.A., are editors of this column.

Figure 1. Percentage of employees whose mental health benefits are less generous than their medical benefits

Figure 2. Percentage of employees with limits on mental health benefits, 1999-2000

1. Employee Benefits in Medium and Large Private Establishments. Washington, DC, Bureau of Labor Statistics (various years)Google Scholar

2. Salkever DS, Shinogle J, Goldman H: Mental health benefit limits and cost sharing under managed care: a national survey of employers. Psychiatric Services 50:1631-1633, 1999Link, Google Scholar

3. Sturm R, Gresenz CR, Sherbourne CD, et al: The design of Health Care for Communities: a study of health care delivery for alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health conditions. Inquiry 36:221-233, 1999Medline, Google Scholar