Predictors of Recurrence in Bipolar Disorder: Primary Outcomes From the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD)

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Little is known about clinical features associated with the risk of recurrence in patients with bipolar disorder receiving treatment according to contemporary practice guidelines. The authors looked for the features associated with risk of recurrence. METHOD: The authors examined prospective data from a cohort of patients with bipolar disorder participating in the multicenter Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study for up to 24 months. For those who were symptomatic at study entry but subsequently achieved recovery, time to recurrence of mania, hypomania, mixed state, or a depressive episode was examined with Cox regression. RESULTS: Of 1,469 participants symptomatic at study entry, 858 (58.4%) subsequently achieved recovery. During up to 2 years of follow-up, 416 (48.5%) of these individuals experienced recurrences, with more than twice as many developing depressive episodes (298, 34.7%) as those who developed manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes (118, 13.8%). The time until 25% of the individuals experienced a depressive episode was 21.4 weeks and until 25% experienced a manic/hypomanic/mixed episode was 85.0 weeks. Residual depressive or manic symptoms at recovery and proportion of days depressed or anxious in the preceding year were significantly associated with shorter time to depressive recurrence. Residual manic symptoms at recovery and proportion of days of elevated mood in the preceding year were significantly associated with shorter time to manic, hypomanic, or mixed episode recurrence. CONCLUSIONS: Recurrence was frequent and associated with the presence of residual mood symptoms at initial recovery. Targeting residual symptoms in maintenance treatment may represent an opportunity to reduce risk of recurrence.

Over 90% of patients with bipolar disorder experience recurrences during their lifetimes (1), often within 2 years of an initial episode (2), and the consequences of recurrent illness for patients are substantial (3). Recent randomized, controlled trials have suggested that both newer (4, 5) and older (4) pharmacotherapies are effective in reducing the risk of recurrence. Other studies have suggested efficacy for adjunctive psychosocial interventions in combination with pharmacotherapy (6, 7).

However, results from randomized, controlled trials are difficult to generalize to clinical practice because they typically include only bipolar I patients and exclude those with substantial medical or psychiatric comorbidity, particularly substance abuse. Randomized trials also generally involve monotherapy, even though in clinical practice most patients receive multiple medications (8). Furthermore, randomized pharmacotherapy trials generally do not allow adjunctive psychosocial therapies, even though such interventions have been shown to decrease the risk of recurrence (6). Conversely, naturalistic studies often use select groups (e.g., first-episode patients, bipolar I/psychotic patients), many were conducted before the widespread use of newer pharmacotherapies for bipolar disorder, and all but two included fewer than 100 individuals with bipolar disorder (2, 9–13). Therefore, the extent to which modern treatment approaches may improve outcomes in actual clinical populations with bipolar I and II disorder remains to be established. Likewise, the limited size of most prior naturalistic studies yielded little power to detect clinical predictors of risk of recurrence.

The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD)represents the largest prospective examination of bipolar disorder outcomes conducted to date (14). STEP-BD explicitly allows for the inclusion of patients with medical and psychiatric comorbidity and those who require complex treatment regimens. It uses a common disease management model in which clinicians use evidence-based treatment guidelines (14) that encourage the use of core psychosocial interventions (in addition to medications) in all patients. As such, STEP-BD allows for the assessment of longitudinal illness course and outcomes in a generalizable cohort of patients who receive “best practice” therapeutic regimens with modern pharmacotherapies.

We analyzed prospective follow-up data from STEP-BD to examine two related issues of substantial clinical importance. First, we investigated recurrence among patients who initially achieved recovery from a mood episode to estimate the effectiveness of guideline-based treatment with contemporary pharmacotherapies. Second, we examined the association between clinical features and risk of recurrence, hypothesizing that characteristics previously suggested as possible predictors of recurrence, including subsyndromal or residual symptoms (15), psychiatric comorbidity (16), and prior number of episodes (17, 18), would predict risk in this cohort as well.

Method

Study Overview

STEP-BD is a multicenter study designed to evaluate longitudinal outcomes in individuals with bipolar disorder. The overall study combines a large prospective naturalistic study using a common disease-management model and a series of randomized, controlled trials that share a battery of common assessments (14). All participants receive standardized ongoing assessment, regardless of whether they are participating in randomized treatment; this report includes data from the prospective naturalistic study only.

Participants

The study was approved by the human research committees (institutional review boards) of all participating treatment centers and the data coordinating center, and oral and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation in study procedures. For participants ages 15–17, written assent was obtained, with written informed consent obtained from a parent or legal guardian. STEP-BD participation was offered to all diagnostically eligible patients seeking outpatient treatment. To enter STEP-BD, the participants were required to be at least 15 years of age and to meet DSM-IV criteria (19) for bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymia, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar subtype. Exclusion criteria were limited to an unwillingness or inability to comply with study assessments, an inability to give informed consent, or being an inpatient at the time of enrollment (although hospitalized patients could enter STEP-BD after discharge). The present report draws on the first 2,000 participants to enter STEP-BD with up to 2 years of data from the point of enrollment, focusing on the 858 who entered in a symptomatic state and achieved recovery during those 2 years.

Assessments

The Affective Disorder Evaluation (ADE) (14) uses adaptations of the mood and psychosis modules from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (19). It was administered by ADE-certified psychiatrists to all participants at study entry and was the primary means of establishing a diagnosis. The ADE also included a systematic assessment of lifetime and recent course of illness based on patient reports, including age at illness onset, number of lifetime prior episodes, number of episodes, proportion of days in each mood state in the prior year, and longest period of euthymia.

The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, version 4.4 (MINI), (20) was used to confirm bipolar diagnosis and establish comorbid axis I illness and was administered by MINI-certified study clinicians upon study entry. The MINI is a brief structured interview designed to identify the major axis I psychiatric disorders in DSM-IV and ICD-10. The MINI has been compared to DSM-III-R and has been found to have acceptably high validation and reliability scores (20). The MINI and ADE were completed by different study clinicians, and a consensus diagnosis of one of the eligible bipolar disorders was required on both the ADE and MINI for study entry. Where the two instruments initially yielded discordant results, a consensus conference was convened to review all sources of data and determine best-estimate diagnosis and eligibility.

The clinical monitoring form (CMF) (14, 21), which collects DSM-IV criteria for depressive, manic, hypomanic, or mixed states, was administered by CMF-certified study clinicians at each follow-up visit. Each criterion is scored on a 0–2 scale, where 1 or greater is syndromal and 0.5 is subthreshold. In addition to characterizing current mood state (over the past 7 days), the CMF produces a total score for current depressive symptoms and manic symptoms, which have been shown to be highly correlated with standard mood rating scales, including the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (22) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (14, 21, 23). In completing the CMF, as with similar rating scales, the clinician is expected to use any available sources of information, including direct observation and questioning, as well as collateral informants when available.

Acceptable interrater agreement was established by requiring all treating psychiatrists to complete standardized training in the administration of the CMF and ADE, which required scoring of videotaped interviews. Upon completing this training, intraclass correlation coefficients for individual SCID mood items ranged from 0.83–1.00, with most items greater than 0.95, suggesting a high degree of uniformity in symptom ratings. Periodic monitoring was continued during the study to ensure that rating standards were maintained (14). The MADRS and the Young Mania Rating Scale were also administered on a quarterly basis for the first year and then every 6 months thereafter by trained raters as an independent validation of CMF ratings.

Intervention

Because STEP-BD was designed as an effectiveness study, participants in the Standard Care Pathway of STEP-BD could receive any intervention felt to be clinically indicated by their clinician. However, study clinicians were trained (with a minimum of 20 credit hours of basic teaching related to the management of bipolar disorder, described elsewhere [14]) to use model practice procedures. In addition to the monitoring procedures noted, clinicians used pharmacotherapy guidelines based on published treatment guidelines (24–26). This approach does not require adherence to a specific treatment algorithm. Instead, it emphasizes application of evidence-based treatments at every decision point in treatment rather than mandating a single treatment.

Because adjunctive psychosocial interventions have been reported to augment the efficacy of pharmacotherapies and to reduce treatment costs (6, 7, 27, 28), STEP-BD also incorporated a core psychosocial intervention referred to as collaborative care (14). The protocol specified that participants entering STEP-BD received a workbook and videotape describing this model, which emphasizes alliance-building as well as techniques for managing stress, negative cognitions, problems in interpersonal interactions, and sleep disruption. In collaboration with the treating clinician, participants completed a treatment contract describing their typical mood symptoms and interventions for managing them (29).

Outcomes

The participants were seen in follow-up as often as clinically indicated rather than at a fixed interval. Their clinical state was assessed at each follow-up visit with the CMF and was used to define the mood states that represent the primary outcome measure. Recovery was defined as two or fewer syndromal features of mania, hypomania, or depression for at least 8 weeks, consistent with standard DSM-IV criteria for partial or full remission and with criteria used in the prior National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative Study of Depression (30). Recurrence was defined as meeting the full DSM-IV criteria for a manic, hypomanic, mixed, or depressive episode on any one follow-up visit. Subsyndromal mood symptoms were defined as the presence of more than two syndromal features of either depression, mania, or hypomania without meeting the full DSM-IV criteria for a mood episode. Occurrence of subsyndromal mood symptoms during follow-up was not considered a recurrence.

Statistical Analysis

The at-risk population for this analysis, drawn from the first 2,000 participants enrolled in STEP-BD, was defined as the individuals (N=858) who had not recovered by study entry (i.e., were experiencing at least three clinically significant features of either mania, hypomania, or depression or had experienced these symptoms within 8 weeks) but who subsequently achieved a recovered state (i.e., two or fewer clinically significant features of mania, hypomania, or depression).

Time to an event/censoring was defined as the number of days from baseline (first recovered visit) to the time at first event (recurrence) or, for the participants who had no recurrence, the last CMF available within the 2 years of follow-up from the time of enrollment. In the analysis of depressive recurrence, a case with any manic, hypomanic, or mixed episode occurring before the depressive relapse was treated as censored at the time of first nondepressive relapse and vice versa for the manic/mixed recurrence analysis.

Cox regression models were used to examine the association between individual predictors and time to depressive recurrence and time to manic/hypomanic/mixed recurrence. All terms were then entered into a stepwise Cox regression model, with p value to enter or be removed from the model set at 0.05.

For the bivariate analyses of putative predictor variables, we elected to test primary (a priori) hypotheses with an alpha of 0.05. These variables included prior number of mood episodes, axis I comorbidity, and presence of residual manic or depressive symptoms at baseline. For secondary (hypothesis-generating) analyses of univariate predictors, we applied a Bonferroni correction. Thus, for 28 independent comparisons in each experiment (time to depression and time to maniac/hypomaniac/mixed episode), p<0.05/28=0.0018 was considered statistically significant. These variables included sociodemographic data (sex, age at study entry, years of education, marital status, and income), recent clinical course (rapid cycling at baseline; number of manic or depressive episodes in the past year; percent days of depression, anxiety, and mood elevation in the past year by patient report; polarity of most recent episode), lifetime clinical course (age at illness onset, duration of illness, number of hypomanic/manic/mixed episodes and depressive episodes, longest period of euthymia, prior suicide attempts, and lifetime history of psychosis), comorbid psychiatric illness (lifetime or current substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, or eating disorders), and family history of bipolar disorder.

We included p values <0.05 in the presentation of results for two reasons. First, given the clinical importance of recurrence and the paucity of long-term predictors in bipolar disorder, even modest associations were felt to be of potential clinical significance if they can be replicated, and thus, we were more concerned about type II errors. Second, many of the variables examined as predictors are expected to be correlated; full Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons is likely overly conservative.

Results

Demographic and Diagnostic Characteristics

All enrolled participants

Among the first 2,000 participants to enter STEP-BD, there were 530 participants (26.5%) who were recovered and 1,469 participants (73.5%) who were not recovered at study entry (ADE was not completed for one subject). Among those who were not recovered, the current episode was depressive in 522 (26.1%), manic in 58 (2.9%), hypomanic in 72 (3.6%), and mixed in 172 (8.6%). An additional 257 (12.8%) were experiencing subsyndromal mood symptoms, and 388 (19.4%) were recovering (i.e., had achieved a euthymic state but for fewer than 8 weeks).

Participants who recovered from an index episode

Among the participants who were not recovered at study entry, 858 of 1,469 (58.4%) subsequently achieved recovery within up to 2 years of follow-up. Those who achieved recovery were examined in all subsequent analyses. These 858 participants had a mean age of 39.9 years (SD=12.7), and 59.0% were women and 93.6% Caucasian. In all, 609 participants (71.0%) had bipolar I disorder, 203 (23.7%) had bipolar II disorder, 46 (5.4%) had bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, and none had schizoaffective disorder; the mean age of onset was 16.7 years (SD=8.1), and the mean duration of illness was 23.1 years (SD=13.1). A lifetime history of psychosis was present in 315 (38.1%), and 299 (35.6%) reported at least one suicide attempt. Lifetime psychiatric comorbidity included at least one axis I anxiety disorder in 459 (56.0%), including a current anxiety disorder in 303 (37.0%), and at least one substance use disorder in 404 (49.3%), including current substance use disorder in 122 (14.9%).

In the year prior to study entry, these participants reported a mean of 2.7 depressive episodes (SD=4.0) and 2.8 hypomanic, manic, or mixed episodes (SD=5.2); 217 (27.4%) of 858 met criteria for rapid cycling. Proportion of days depressed, anxious, and with an elevated mood in the prior year was 43.9% (SD=27.7%), 31.8% (SD=31.4%), and 20.6% (SD=21.4%), respectively. The mean for longest period of euthymia in the prior 2 years was 132.9 days (SD=171.4).

The index episode at enrollment among those who subsequently achieved recovery was major depression in 257 (30.0%) compared to mood elevation in 149 (17.4%), of which 39 (5%) experienced mania, 41 (5%) hypomania, and 69 (8%) a mixed state. An additional 452 (53%) of the participants were experiencing subsyndromal symptoms at study entry.

Prediction of Recurrences

Median follow-up in this 858-patient cohort was 94.5 weeks following study entry and 56.2 weeks following recovery. The mean number of follow-up visits per month was 1.1 (SD=1.0). During longitudinal treatment and monitoring, 416 participants (8.5%) experienced recurrence. Median time to recurrence of any mood episode was 44.9 weeks (95% CI=37.6–53.1). More than twice as many developed depressive episodes (N=298, 34.7%) as mood elevation episodes (N=118, 13.8%). The latter included 50 (6%) with mania, 41 (5%) with hypomania, and 27 (3%) with mixed states. The time until 25% of the participants experienced a depressive episode was 21.4 weeks (95% CI=18.6–25.3) and until 25% experienced a manic/hypomanic/mixed episode was 85.0 weeks (95% CI=65.0–not calculable).

In total, 644 participants’ illness recurred within 1 year, or they were followed for at least 1 year after achieving recovery. By 1 year, 144 of 644 (22.4%) had experienced depressive recurrence, and 41 of 644 (6.4%) had experienced manic/hypomanic/mixed recurrence.

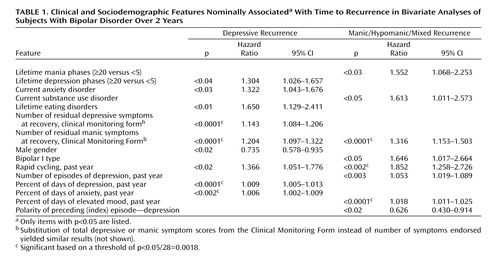

We first examined the association between lifetime comorbid axis I psychiatric illness and recurrence (Table 1). The presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder was not significantly associated with risk of recurrence (n.s.), nor was a lifetime substance use disorder (n.s.). However, a current substance use disorder at study entry was associated with an increased risk of manic but not depressive recurrence. Conversely, a current anxiety diagnosis at study entry was associated with increased risk of depressive but not manic recurrence. Anxiety symptoms after achieving recovery are the subject of a separate report (31). Finally, the presence of a lifetime eating disorder was significantly associated with depressive recurrence.

We next examined the relationship between the number of lifetime mood episodes and the risk of recurrence. Compared to individuals with fewer than five episodes, those experiencing 20 or more prior episodes of either depression or (hypo)mania had a greater risk of recurrence to that pole (Table 1). For those with fewer prior episodes, no significant increase in risk of recurrence was observed.

We also postulated an association between residual symptoms and a greater risk of recurrence. Both residual depressive and manic symptoms were significantly associated with risk of recurrence (Table 1). Residual manic symptoms but not depressive symptoms at recovery were significantly associated with risk of manic/hypomanic/mixed episode recurrence.

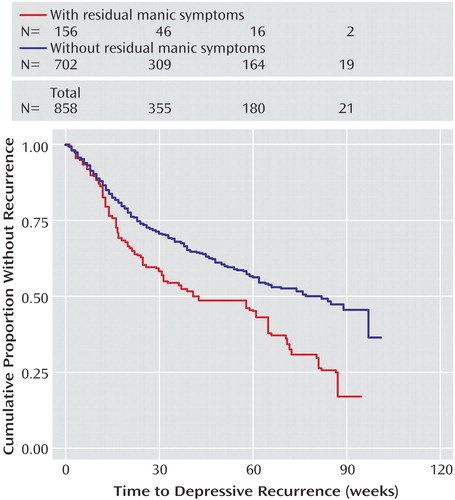

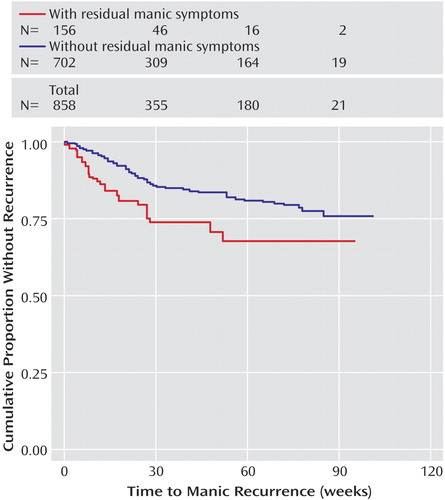

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between time to recurrence and residual mood elevation symptoms, comparing the quintile with the greatest residual symptom burden (corresponding to two or more residual symptoms) with all other participants. The presence of two or more residual threshold or subthreshold symptoms of mood elevation was significantly associated with a shorter time to recurrence of either depression (log rank p=0.002) or mood elevation (log rank p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Table 1 depicts baseline sociodemographic and clinical variables that were associated with time to recurrence of depression or mood elevation. After correction for multiple comparisons, a greater proportion of days depressed and proportion of days anxious in the past year were associated with depressive recurrence. Similarly, the proportion of time spent in a manic/hypomanic state in the past year was significantly associated with a shorter time to manic/hypomanic/mixed episode recurrence, as was the presence of rapid cycling in the past year. Other variables that were not statistically associated with a risk of recurrence to either pole (p≥0.05) included age, age at illness onset, duration of illness, education, marital status, income, family history of bipolar disorder, number of hypomanic/manic/mixed episodes in the past year, number of lifetime manic or depressive episodes, and lifetime history of psychosis, substance use disorders, or anxiety disorders.

To identify factors independently associated with time to recurrence, all potential factors were entered into a stepwise regression model of time to depressive relapse and another for time to manic relapse (Table 2). This analysis accounts for the likelihood that many of the possible clinical predictors are likely to be correlated—for example, greater number of episodes and rapid cycling. Residual manic symptoms were associated with time to depressive recurrence, as was the proportion of days with depression and days with anxiety in the prior year. For every additional residual threshold or subthreshold manic symptom present at the time of recovery, the risk of recurrence increased by approximately 20%. For manic recurrence, a greater number of depressive episodes in the prior year was associated with a greater risk of recurrence. Two other markers of chronicity (more days elevated in the prior year and fewer days depressed) were also associated with manic recurrence.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, only slightly more than half of the participants (58.5%) who were symptomatic at study entry achieved recovery during up to 2 years of follow-up. Furthermore, 48.5% of the participants experienced recurrence during up to 2 years of follow-up; the majority of recurrences (70%) were to the depressive pole, with a ratio of 2.5:1 for depressive recurrence versus manic/mixed/hypomanic episodes. Taken together, these results demonstrate that mood episodes in bipolar disorder, and particularly depressive episodes, are prevalent and likely to recur in spite of guideline-based treatments. Indeed, participants in STEP-BD received evidence-based care from specialized clinicians with training in the use of standardized assessments, combination pharmacotherapy, and psychosocial treatments where appropriate. In addition, participants received at minimum a core psychoeducational intervention. The finding that nearly half of the study participants nonetheless suffered at least one recurrence during follow-up highlights the need for development of new interventions in bipolar disorder.

Numerous other recent longitudinal studies report the results of follow-up without guideline-based treatment. Three studies in the past decade followed patients prospectively but naturalistically for at least 2 years; none included hypomania as an endpoint. In the McLean-Harvard First-Episode Mania Study, Tohen et al. (2) reported that 34% of 154 individuals with bipolar I who had achieved recovery from a first manic or mixed episode suffered a recurrence within 2 years (55% of which were manic or mixed episodes); median time to recurrence was 32.3 weeks. A similar study by Bromet et al. (9) examined 103 individuals with bipolar I disorder who were psychotic at the time of initial hospitalization and subsequently achieved remission; these patients were followed for 4 years. Median time to recurrence in this sample was 87 weeks, with 24.3% suffering recurrence by 6 months, 35.9% by 1 year, and 61.2% by 4 years. Three-quarters of this sample were manic at study entry, so it is perhaps not surprising that the majority of recurrences were also to manic or mixed episodes. In an outpatient study that did not examine first-admission patients (N=82), Gitlin and colleagues (10) found that mean survival was nearly 3 years, and the 1-year recurrence rate was 37%. Finally, a fourth cohort, the NIMH Collaborative Study of Depression, included 152 individuals with bipolar I who achieved recovery during prospective follow-up (30). That study found 1-year recurrence rates between 48% and 57%; of note, it was completed before more modern pharmacotherapies for bipolar disorder other than lithium were available and considered minor depression and hypomania as recurrence, unlike the three more recent studies.

Prospective longitudinal outcome studies in bipolar disorder thus exhibit substantial heterogeneity in terms of patient populations, available treatments (including psychosocial interventions), definitions of recurrence, and use of algorithms or guidelines. Such heterogeneity precludes direct comparison of our outcomes with those of prior studies. What is clear is that in all of these studies, recurrence rates remain substantial.

We confirmed several predictors of recurrence. In particular, residual mood symptoms early in recovery appear to be a powerful predictor of recurrence, particularly for depression. Risk of depressive recurrence increases by 14% for every DSM-IV depressive symptom present at recovery and by 20% for every manic/hypomanic symptom present at recovery. This is consistent with the work of Keller et al. (15) that found that subsyndromal symptoms were associated with risk of recurrence, although that study examined lithium-treated patients only and did not specifically examine residual symptoms at the time of initial recovery. Data from antidepressant trials in major depressive disorder also highlight the importance of complete symptom remission as a treatment goal (32). Given the prevalence of residual or subthreshold symptoms among bipolar I and II patients (33, 34), this finding suggests that aggressively targeting subthreshold symptoms may offer a substantial opportunity to improve outcomes. Of note, residual manic symptoms appear to confer risk for both manic and depressive recurrence. The elevated risk for depressive recurrence is only evident beyond about 12 weeks (Figure 1), suggesting that it is unlikely to indicate solely what has been referred to as “postmanic depression”—i.e., individuals who transition directly from mania to depression (35).

Because many of the hazard ratios presented refer to continuous variables (e.g., percent of days with anxiety symptoms), the magnitude of effect can appear small. However, these statistical differences do appear to be clinically significant. For example, with a hazard ratio of 1.008 for percent days anxious, if two otherwise similar participants have a 25% difference in days with anxiety, the more anxious patient is nearly 5% more likely to have illness recurrence before the less anxious patient.

Two previous naturalistic studies suggested poorer outcomes for individuals with psychiatric comorbidity (13, 18), and previous analyses of STEP-BD data likewise found evidence of a poorer retrospective (16) and prospective course (unpublished paper by M.W. Otto et al.) among participants with anxiety disorders. Consistent with these findings, a greater proportion of days with significant anxiety in the year prior to study entry was associated with a greater risk for depressive recurrence. We found no evidence of an association between lifetime substance use disorders and earlier recurrence beyond the modest association evident for current substance abuse or dependence. Of interest, the presence of a comorbid eating disorder also appears to increase the risk for depressive recurrence; whether it is simply a marker for more severe illness or represents an opportunity for intervention to improve outcomes merits further study.

We note four important limitations for these analyses. First, although STEP-BD was designed as an effectiveness study (14), several study features affect its generalizability. The participants were enrolled in outpatient settings, primarily in bipolar specialty care clinics, and were predominantly Caucasian. Patients with a particularly severe or chronic course requiring frequent hospitalizations may have been too ill to attend the baseline visit and adequate follow-up. This bias may also be reflected in the limited number of individuals with current substance abuse or dependence participating in the study. Conversely, many bipolar patients are managed in primary care practices or general psychiatric practices; generally stable patients might be less willing to change clinicians to enter a study such as STEP-BD. In essence, then, the STEP-BD sample probably best captures individuals with moderate illness: ill enough to require regular visits and seek specialty care but stable enough to comply with study entry procedures.

An additional limitation is the absence of data on clinician adherence to treatment guidelines. Clinicians received standardized education in the application of evidence-based guidelines at critical decision points, but individual treatment decisions were not monitored in an ongoing fashion. Our results, therefore, are not directly comparable to those of monitored and supervised intervention studies (36, 37), which also have limitations in generalizability. Moreover, even guidelines that purport to be evidence-based are often limited by a paucity of randomized, controlled data for next-step interventions.

A third limitation is our decision to first examine general predictors of recurrence rather than the effects of individual treatments. The “effectiveness” design of the STEP-BD standard care pathway allows for multiple reasonable interventions at each step in treatment rather than dictating a single intervention. Identifying non-treatment-specific factors associated with outcome will, however, facilitate future examinations of treatment response in this and other cohorts.

Finally, to mirror clinical practice, STEP-BD used visits at clinically appropriate but varying intervals and relied on an assessment of recent mood symptoms. It is therefore possible that participants could avoid follow-up visits during acute episodes; this might account in part for the far greater proportion of depressive than manic episodes, for example. The CMF could be completed based on other sources of information (hospitalization, contact with family members), which decrease this risk. Similarly, patients with residual symptoms might be seen more frequently and thus have recurrence detected earlier. In fact, however, in a comparison of frequency of visits, no significant differences were noted (results not shown).

Overall, these results suggest that in spite of modern evidence-based treatment, bipolar disorder remains a highly recurrent, predominantly depressive illness. Predictors of risk of recurrence, which might be useful in stratifying patients to more or less intensive maintenance follow-up and treatment included early residual symptoms, highlighting the need to target full remission, as in major depressive disorder (32). A better understanding of the way in which these predictors may moderate (or mediate) risk of recurrence could also suggest directions toward novel strategies to modify this risk.

|

|

Received July 29, 2005; revision received Nov. 8, 2005; accepted Nov. 9, 2005. From the Bipolar Clinical and Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic and Epidemiological Data Center, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh; Stanford University Medical School, San Francisco; Boston University, Boston; the University of Colorado, Boulder; and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Perlis, Massachusetts General Hospital, ACC 812, 15 Parkman St., Boston, MA 02114; [email protected] (e-mail).Dr. Perlis was supported by an NIMH K23 Career Development Award. Funded in whole or in part by NIMH grant (N01 MH-80001) (STEP-BD) and K23 MH-067060 (to Dr. Perlis).The authors report no conflict of interest. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIMH.Additional information on this study accompanies the online version of the article.

Figure 1. Relationships Between Residual Manic Symptoms and Time to Depressive Recurrence in Subjects With Bipolar Disorder Over 2 Years

Figure 2. Relationships Between Residual Manic Symptoms and Time to Manic Recurrence in Subjects With Bipolar Disorder Over 2 Years

1. Solomon DA, Keitner GI, Miller IW, Shea MT, Keller MB: Course of illness and maintenance treatments for patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:5–13Medline, Google Scholar

2. Tohen M, Zarate CA Jr, Hennen J, Khalsa H-MK, Strakowski SM, Gebre-Medhin P, Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ: The McLean-Harvard First-Episode Mania Study: prediction of recovery and first recurrence. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:2099–2107Link, Google Scholar

3. Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RM: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J Affect Disord 1994; 31:281–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Goodwin GM, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Grunze H, Kasper S, White R, Greene P, Leadbetter R: A pooled analysis of 2 placebo-controlled 18-month trials of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance in bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:432–441Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Tohen M, Greil W, Calabrese JR, Sachs GS, Yatham LN, Oerlinghausen BM, Koukopoulos A, Cassano GB, Grunze H, Licht RW, Dell’Osso L, Evans AR, Risser R, Baker RW, Crane H, Dossenbach MR, Bowden CL: Olanzapine versus lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: a 12-month, randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1281–1290Link, Google Scholar

6. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Torrent C, Comes M, Corbella B, Parramon G, Corominas J: A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:402–407Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Richards JA, Simoneau TL, Suddath RL: A randomized study of family-focused psychoeducation and pharmacotherapy in the outpatient management of bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:904–912Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Grochocinski VJ, Cluss PA, Houck PR, Stapf DA: Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals in a bipolar disorder case registry. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:120–125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bromet EJ, Finch SJ, Carlson GA, Fochtmann L, Mojtabai R, Craig TJ, Kang S, Ye Q: Time to remission and relapse after the first hospital admission in severe bipolar disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005; 40:106–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gitlin MJ, Swendsen J, Heller TL, Hammen C: Relapse and impairment in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1635–1640Link, Google Scholar

11. Tohen M, Stoll AL, Strakowski SM, Faedda GL, Mayer PV, Goodwin DC, Kolbrener ML, Madigan AM: The McLean First-Episode Psychosis Project: six-month recovery and recurrence outcome. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:273–282Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Harrow M, Goldberg JF, Grossman LS, Meltzer HY: Outcome in manic disorders: a naturalistic follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:665–671Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Goldberg JF, Harrow M, Grossman LS: Course and outcome in bipolar affective disorder: a longitudinal follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:379–384Link, Google Scholar

14. Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, Bauer M, Miklowitz D, Wisniewski SR, Lavori P, Lebowitz B, Rudorfer M, Frank E, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Bowden C, Ketter T, Marangell L, Calabrese J, Kupfer D, Rosenbaum JF: Rationale, design, and methods of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:1028–1042Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Kane JM, Gelenberg AJ, Rosenbaum JF, Walzer EA, Baker LA: Subsyndromal symptoms in bipolar disorder: a comparison of standard and low serum levels of lithium. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:371–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Pollack MH (STEP-BD Investigators): Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2222–2229Link, Google Scholar

17. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Clayton PJ, Klerman GL, Hirschfeld RM: Differential outcome of pure manic, mixed/cycling, and pure depressive episodes in patients with bipolar illness. JAMA 1986; 255:3138–3142Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Tohen M, Waternaux CM, Tsuang MT: Outcome in mania: a 4-year prospective follow-up of 75 patients utilizing survival analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1106–1111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

20. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 20):22-33Google Scholar

21. Sachs GS, Guille C, McMurrich SL: A clinical monitoring form for mood disorders. Bipolar Disord 2002; 4:323–327Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429–435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Sachs GS, Printz DJ, Kahn DA, Carpenter D, Docherty JP: The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder 2000. Postgrad Med 2000; April Special Number:1-104Google Scholar

25. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(April suppl)Google Scholar

26. Bauer MS, Callahan AM, Jampala C, Petty F, Sajatovic M, Schaefer V, Wittlin B, Powell BJ: Clinical practice guidelines for bipolar disorder from the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:9–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Huxley NA, Parikh SV, Baldessarini RJ: Effectiveness of psychosocial treatments in bipolar disorder: state of the evidence. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2000; 8:126–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Craighead WE, Craighead LW: The role of psychotherapy in treating psychiatric disorders. Med Clin North Am 2001; 85:617–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Otto MW, Reilly-Harrington N, Sachs GS: Psychoeducational and cognitive-behavioral strategies in the management of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2003; 73:171–181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Endicott J, Mueller TI: Bipolar I: a five-year prospective follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993; 181:238–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Thase ME, Sloan DM, Kornstein SG: Remission as the critical outcome of depression treatment. Psychopharmacol Bull 2002; 36(4 suppl 3):12-25Google Scholar

32. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Rice JA, Keller MB: The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:530–537Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser JD, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Keller MB: A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:261–269Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Gitlin M, Boerlin H, Fairbanks L, Hammen C: The effect of previous mood states on switch rates: a naturalistic study. Bipolar Disord 2003; 5:150–152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Suppes T, Rush AJ, Dennehy EB, Crismon ML, Kashner TM, Toprac MG, Carmody TJ, Brown ES, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Witte BP, Trivedi MH, Miller AL, Altshuler KZ, Shon SP: Texas Medication Algorithm Project, Phase 3 (TMAP-3): clinical results for patients with a history of mania. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:370–382Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Unutzer J, Bauer MS, Operskalski B, Rutter C: Randomized trial of a population-based care program for people with bipolar disorder. Psychol Med 2005; 35:13–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Perlis RH, Keck PE: The Texas implementation of medication algorithms update for treatment of bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:818–820Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar