Structural Stigma in State Legislation

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This article discusses examples of structural stigma that results from state governments' enactment of laws that diminish the opportunities of people with mental illness. METHODS: To examine current trends in structural stigma, the authors identified and coded all relevant bills introduced in 2002 in the 50 states. Bills were categorized in terms of their effect on liberties, protection from discrimination, and privacy. The terms used to describe the targets of bills were examined: persons with "mental illness" or persons who are "incompetent" or "disabled" because of mental illness. RESULTS: About one-quarter of the state bills reviewed for this survey related to protection from discrimination. Within that category, half the bills reduced protections for the targeted individuals, such as restriction of firearms for people with current or past mental illness and reduced parental rights among persons with a history of mental illness. Half the bills seemed to expand protections, such as those that required mental health funding at the same levels provided for other medical conditions and those that disallowed use of mental health status in child custody cases. Legislation frequently confuses "incompetence" with "mental illness." CONCLUSIONS: Examples of structural stigma uncovered by surveys such as this one can inform advocates for persons with mental illness as to where an individual state stands in relation to the number of bills that affect persons with mental illness and whether these bills expand or contract the liberties of this stigmatized group.

Several recent studies have examined how the stigma associated with mental illness impedes the opportunities available to people with these disorders (1,2,3,4). Almost all these studies have framed stigma as an individual-level psychological construct—that is, the personal attitudes about mental illness that lead to prejudice and discriminatory behavior.

Sociologists have described an alternative form of prejudice and discrimination that has been called structural (5,6,7,8,9). Structural discrimination is formed by sociopolitical forces and represents the policies of private and governmental institutions that restrict the opportunities of stigmatized groups. For example, Jim Crow laws, which extended from the end of the 19th to the middle of the 20th century, were a form of public institutional discrimination often called de jure discrimination. These laws, largely enacted by southern states, explicitly undermined the rights of African Americans in such vital areas as employment, education, and public accommodation. Although African Americans were not harmed directly by the prejudicial attitudes and discriminatory behavior of individuals, societal rules were preventing them from fully enjoying life opportunities.

We used a 1999 survey of existing state laws (10) as evidence of structural discrimination related to mental illness (11). Results of that survey showed that about a third of the 50 states restrict the rights of an individual with mental illness to hold elective office, participate on juries, and vote. Even greater limitations were evident in the family domain. About 50 percent of states restrict the child custody rights of parents who have a mental illness. These cases are all examples of structural discrimination, in the guise of state laws, diminishing the life opportunities of people with mental illness. Other studies have shown similar legislative patterns for people with mental illness (12) and for other stigmatized groups with health conditions, such as people with AIDS (13).

Surveys of the existing body of laws are limited as a means of judging whether legislatures currently are promoting bills and policies that restrict the rights of people with mental illness. For example, the profile of discrimination outlined by a legal survey conducted by Hemmens and colleagues (10) may represent legislative inertia; once a law is passed, it generally remains on the books unless legislatures actively vote to expunge it. To bypass this problem, surveys of current legislative activity pertaining to mental illness are necessary to determine whether state legislatures are becoming more or less prejudicial toward people with mental illness.

We report on one such survey here by examining all legislative activity related to mental illness in all state legislatures from January 1 to December 31, 2002. Legislative activity is a complex and multistage phenomenon that may include a statute's being introduced by a legislator, passing a committee, passing one house of the legislature, passing both houses, and being signed by the governor. We decided to examine legislative activity at all stages, because all reflect some formal interest by some segment of state government on issues relevant to structural discrimination. Policies relevant to structural discrimination were grouped into three areas: liberties (the procedural or substantive rights of people with mental illness with respect to refusing treatment or having restrictions placed on physical liberty), protections from discrimination (policies that prevent or promote discrimination in housing, employment, or other benefits and services), and privacy rights (confidentiality for people with mental illness).

Research by Hemmens and colleagues (10) suggested that states generally targeted and were more restrictive of a group of people who were identified as "mentally ill" rather than "incompetent." "Mental illness" is a term the public seems to use as a general descriptor of people with psychiatric disorders. "Incompetence" is a legal term referring to people who, on account of mental illness or another condition, lack the capacity to make specific kinds of decisions, such as those concerning money management or health care. In this survey we distinguished between legislation affecting persons labeled as mentally ill and legislation focusing on incompetence, and we postulated that restrictions on liberty, rights protection, or privacy solely on the basis of mental illness label are further evidence of structural discrimination. Such legislation restricts the rights of a large class of people whose capacity is not significantly impaired by mental illness.

Methods

The LexisNexis online legal research system contains a complete and comprehensive listing of state legislation at all stages of the legislative process. We searched LexisNexis for activity at all stages of the legislative process as a research project of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) Treatment/Recovery Information and Advocacy Database (TRIAD). Interestingly, findings did not differ on the basis of stage in the legislative process, so data are presented here aggregated across the stages. We searched all activity from January 1 to December 31, 2002, by using three search terms that were tested in a pilot study: "mental illness," "mental health," and "psychiatry." Bills were excluded if they dealt only with children with mental illness, sex offenders, people with mental retardation, or mentally gifted people.

We conducted a focus group as a basis for the content validity of the coding manual for this study. The focus group included eight members of mental health advocacy groups with expertise in policy. They were asked to provide examples of current and past legislation that might be construed as intentionally or unintentionally discriminatory for people with mental illness. Subsequent analyses of the transcript of the focus group yielded three categories of bills: those that expand or contract liberties (the intent or goal of a bill is to deal with procedural or substantive rights of persons with mental illness with respect to refusing treatment or restrictions on physical liberty), those that expand or contract protections against discrimination (the bill deals with protections for people with mental illness in terms of housing, employment, or other benefits or services), and those that expand or contract privacy (bills that deal with privacy or confidentiality for persons with mental illness). The content of these categories was independently validated by mental health attorneys from the University of Chicago School of Law (the third author) and the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law. Note that we coded bills strictly on the basis of their intended effect on resources, liberties, protection from discrimination, and privacy. We did not make judgments as to the actual or practical effect of the legislation once implemented.

The resulting eight-page coding manual, available from the first author, included 18 codes and corresponding response categories. The coding manual also included an extensive glossary to guide coding. Two independent raters coded all the bills by using the coding manual, deciding whether the individual bill was consistent with these categories. Initial percentage agreement for eight states ranged from 85 percent to 93 percent. Raters met and consensually agreed on a code for cases in which they differed. Using this method, the raters also coded whether the bill contracted or expanded resources or services for people with mental illness; this information was gathered as a baseline of legislative activity, because funding bills typically represent the most common form of activity. Finally, the target of bills related to liberties or discrimination protections was coded in terms of whether the bill referred to people with a diagnosis of a mental illness or to people who were disabled or incompetent.

No institutional review board approval was sought for this study, because all coded information was limited to legislative activity that was available on public Web sites. No informed consent was necessary.

Results

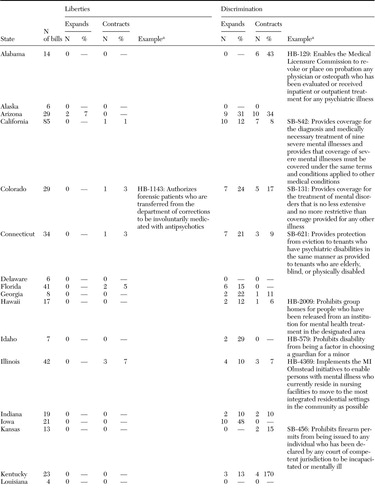

Table 1 provides a state-by-state summary of laws in the legislative process in 2002. The entire findings of our analysis, including the summaries of every bill, and the state-specific Web site where additional information about the bill can be obtained, may be reviewed at www.stigmaresearch.org/projects/legis. Our search terms failed to yield legislative activity in three states: Arkansas, Montana, and Oregon. Searches from two other states—North Dakota and Texas—yielded only prefiled bills—that is, bills that legislators have not yet introduced. The remaining 45 states were involved in 968 bills related to mental illness, ranging from three bills in South Dakota to 85 in California. More than two-thirds focused largely on resource issues. Roughly 66 percent of these bills had the intention of increasing the amount or quality of resources for people with mental illness; only 3.5 percent had the intention of diminishing resources.

Liberties

Overall, only 42 of the 968 mental health bills in 2002 were related to liberties, with more than 75 percent contracting liberties. West Virginia (four bills) and Illinois and Michigan (three bills) had the most bills rated as contracting liberties. Examples are legislation that permits involuntary medication for people transferred from the Department of Corrections (Colorado) and ordering assisted outpatient treatment for people with mental illness with a history of nonadherence to treatment (Michigan). Missouri provided an example of legislation that expanded liberties, enacting a form of advance directive.

Protections from discrimination

Far more bills were related to protections (224 of 968, or 23.1 percent). Bills were about evenly divided between those that expanded protections and those that contracted them. California and Iowa (ten bills each), Arizona (nine bills), and Colorado, Connecticut, and New Jersey (seven bills each) had the most bills that expanded protections from discrimination. Examples from across the United States include several bills requiring mental health funding at levels provided for other medical conditions (for example, California, Colorado, New Jersey, and Rhode Island), disallowing use of mental health status in child custody (Idaho and Utah), and including eviction protections that had been provided to other people with disabilities to individuals with psychiatric disabilities (Connecticut). Missouri (with 13 bills), Arizona (nine bills), and California (seven bills) had the most legislation that seemed to contract protections. Examples include bills that restrict access to firearms for people with current or past mental illness (Kansas, Maryland, New Hampshire, and Ohio), diminish parental rights of individuals with a history of mental illness (Oklahoma and New York), and restrict placement of mental health programs in certain neighborhoods (Hawaii and Michigan).

Privacy

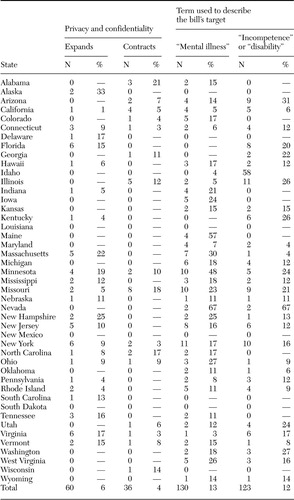

Table 2 summarizes bills related to privacy and confidentiality. About 10 percent of all bills (96 of 968) dealt with privacy issues; about two-thirds of those bills expanded privacy rights, and one-third diminished them. Florida, Virginia, and New York had the most bills that expanded privacy (six bills each), whereas Missouri had the most bills that contracted privacy (eight bills). Most of those that expanded privacy enlarged protections against disclosure of mental health records. An example of diminished privacy rights is sharing of mental health records for reasons of public safety.

"Mental illness" versus "incompetence"

Finally, we examined how the target of a bill was framed (Table 2): people with mental illness (or some corresponding diagnosis) or people with incompetence or disabilities due to mental illness that prevent the person from fully enjoying a right or life opportunity. A total of 253 bills (26.1 percent of the 968) were judged to be relevant to this coding. Of these, 48.6 percent were targeted at individuals who were labeled as incompetent or disabled, and the remainder were targeted at those who were labeled as having a mental illness. Florida (eight bills), Illinois (11 bills), Missouri (nine bills), and New York (ten bills) produced the most bills targeting persons labeled as incompetent or disabled, whereas Minnesota (ten bills), Missouri (ten bills), and New York (11 bills) yielded the most bills targeting persons labeled as having a mental illness.

Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this study was to examine current state legislative activity as a source of examples of structural stigma, with the latter concept operationalized as governmental rules and regulations that effectively discriminate against a stigmatized class—people with mental illness. We developed a method for identifying all legislation related to mental illness in a year and consensually coding bills in terms of four key areas: liberties, discrimination protections, privacy, and language used to describe the target of the legislation. Aggregate findings across all states led to some interesting conclusions. Most bills related to mental health are funding bills; comparatively, states are not drafting much legislation related to liberties. States are considering a significantly larger number of bills related to protection from discrimination, with the bills almost evenly split in terms of whether they expand or contract the protections. Bills that increased discrimination included bills from two states that diminished the parental rights of individuals with a history of mental illness, echoing the restrictions on family rights found in the earlier survey by Hemmens and colleagues (10). However, two states expanded protections in family rights by disallowing the use of some mental health information in child custody decisions.

Several states also limited firearm privileges for people with mental illness. At first, this might seem to be a reasonable action to promote public safety—only those who are competent to use guns should be permitted to do so. However, this restriction is an example of a larger concern in the law—the stigma of targeting people with mental illness per se rather than people who are incompetent as a result of having a mental illness (11). Note that the discrimination in these gun laws is not preventing those who are incompetent because of mental illness from owning or otherwise obtaining guns safely. Rather, the discrimination resides in the assumption that people who are labeled as being mentally ill are not competent to use guns. A majority of individuals who are labeled as being mentally ill by virtue of being hospitalized or receiving mental health care are in touch with reality, not psychotic or homicidal (14). Thus those who are labeled as mentally ill are being discriminated against by virtue of their class. In a separate analysis, we found states split in terms of their sensitivity to whom the target of a law should be. Of the bills that fall into this category, about half targeted persons with a mental illness and half targeted those who were labeled as being incompetent.

There are limitations to the method used in this kind of survey. Summarizing one year of legislative activity misses equally pertinent activity that might have preceded or followed the index legislative session. This problem could be diminished by tracking legislation annually. Another problem is that the effects of individual bills are not equal. Clearly, some bills have minor if any effect whereas others might have a much greater impact on individual rights or opportunities. Finally, the survey reported here did not place the bills in context. It did not specify the history of a bill or whether it was an amendment of a previous bill. Success in the legislative process—for example, a bill's being enacted—is a more accurate reflection of a state's role in increasing or reducing structural discrimination. Many bills may be introduced in state legislatures as a courtesy or constituent service but have little chance of passing. This may be equally true of bills that expand liberties, rights, or privacy as it is of those that diminish them. Unfortunately, the limited number of bills enacted in one year is insufficient for statistical tests. Follow-up research over multiple years may provide a sufficiently large sample for a powerful test of the stage question.

One goal of this study was to provide further information about current legislative activity in the various states as a source of examples of structural discrimination. Local advocates might wish to educate their representatives and senators about subtle forms of stigma and discrimination in cases in which relatively large numbers of bills contracted liberties and protections while expanding discrimination. Perhaps more compelling were the specific examples—advocates may have reasons to be concerned with legislatures that prohibit group homes for people released from a psychiatric institution or defining an unfit parent in terms of mental illness. Similarly, advocates should be attentive to bills that seem to be promoting liberties and discrimination protections, publicly endorsing model legislation that advances these goals. Identifying examples of structural stigma is the needed first step for advocates to ensure the opportunities of people with mental illness are not diminished by legislative fiat.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part through a contract with NAMI.

All authors except Mr. Heyrman and Dr. Hall are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. Mr. Heyrman is with the Law School of the University of Chicago. Dr. Hall is affiliated with the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) based in Arlington, Virginia. Send correspondence to Dr. Corrigan at the Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation at Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, 1033 University Place, Suite 440, Evanston, Illinois 60201 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Number of bills per state and percentage of total bills in the state in 2002 that reflected expansion or contraction of liberties and protection from discrimination against persons with mental illness

|

Table 2. Privacy and confidentiality aspects of state bills in 2002 and bills' use of "mental illness" and "incompetence" or "disability" as terms for the target of the bill

1. Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, et al: Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health 89:1328–1333, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC, et al: An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44:162–179, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Phelan JC, Cruz-Rojas R, Reiff M: Genes and stigma: the connection between perceived genetic etiology and attitudes and beliefs about mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 6:159–185, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Ottati V: Police officers' attitudes toward and decisions about persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:46–53, 2004Link, Google Scholar

5. Hill RB: Structural discrimination: the unintended consequences of institutional processes, in Surveying Social Life: Papers in Honor of Herbert H Hyman. Edited by O'Gorman HJ. Middletown, Conn, Wesleyan University Press, 1988Google Scholar

6. Merton RK: The bearing of empirical research upon the development of social theory. American Sociological Review 13:505–515, 1948Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Pincus FL: From individual to structural discrimination, in Race and Ethnic Conflict: Contending Views on Prejudice, Discrimination, and Ethnoviolence. Edited by Pincus FL, Ehrlich HJ. Boulder, Colo, Westview Press, 1999Google Scholar

8. Wilson WJ: The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, The Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1990Google Scholar

9. Link BG, Phelan JC: Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology 27:363–385, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Hemmens C, Miller M, Burton VS, et al: The consequences of official labels: an examination of the rights lost by the mentally ill and the mentally incompetent ten years later. Community Mental Health Journal 38:129–140, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC: Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:481–492Google Scholar

12. Burton VS: The consequences of official labels: a research note on rights lost by the mentally ill, mentally incompetent, and convicted felons. Community Mental Health Journal 26:267–276, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Heywood M, Altman D: Confronting AIDS: human rights, law, and social transformation. Health and Human Rights 5:149–179, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Monahan J: Mental disorder and violent behavior: perceptions and evidence. American Psychologist 47:511–521, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar