Police Officers' Attitudes Toward and Decisions About Persons With Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A significant portion of police work involves contact with persons who have mental illness. This study examined how knowledge that a person has a mental illness influences police officers' perceptions, attitudes, and responses. METHODS: A total of 382 police officers who were taking a variety of in-service training courses were randomly assigned one of eight hypothetical vignettes describing a person in need of assistance, a victim, a witness, or a suspect who either was labeled as having schizophrenia or for whom no information about mental was provided. These officers completed measures that evaluated their perceptions and attitudes about the person described in the vignette. RESULTS: A 4 × 2 multivariate analysis of variance (vignette role by label) examining main and interaction effects on all subscales of the Attribution Questionnaire (AQ) indicated significant main effects for schizophrenia label, vignette role, and the interaction between the two. Subsequent univariate analyses of variance indicated significant main effects for role on all seven subscales of the AQ and for label on all but the anger and credibility subscales. Significant role-by-label interaction effects were found for the responsibility, pity, and credibility subscales. CONCLUSION: Police officers viewed persons with schizophrenia as being less responsible for their situation, more worthy of help, and more dangerous than persons for whom no mental illness information was provided.

A significant portion of police work involves persons with mental illness (1,2,3,4,5), whom police officers may encounter in a variety of situations (6,7). Police officers have considerable discretion in these situations and often serve as gatekeepers for the criminal justice and mental health systems (8). Thus it is important to understand how officers respond to information that a person has a mental illness.

Surveys of the general population suggest that stereotypes about persons with mental illness may lead to discrimination (9,10). Surveys of persons with mental illness seem to support this assertion in the case of police officers: survey responses indicate that police officers are a significant source of stigmatization and discrimination against persons with mental illness (11,12). The purpose of the study reported here was to examine how knowledge that a person has a mental illness influences police officers' perceptions, attitudes, and responses in several types of situations.

Since Bittner's work in the 1960s (13), only two studies have examined the attitudes and beliefs of police officers about persons with mental illness. One study found that police officers perceived persons with mental illness as being more dangerous than the general population (14). Results of the other study indicated that younger, white officers who had less training about mental illness perceived persons with mental illness as being more dangerous than did their older, nonwhite, and better-trained colleagues (15).

Attribution theory provides an especially useful framework for further consideration of police officers' attitudes toward and responses to citizens with mental illness (16,17). When presented with a situation such as a crime, people try to determine who is responsible. In doing so, people make attributions about the cause and controllability of the event. If the cause of the situation can be attributed to forces within the person's control, then that individual is judged to be responsible. Schmidt and Weiner (18) suggested that emotion (anger or sympathy) mediates cognition (attribution and judgment of responsibility) and action (helping or punishing behavior). If people perceive that the cause of a situation or crime is controllable, they will judge the individual to be responsible, will experience anger, and will respond by punishing or ignoring the person. Conversely, if the cause of the situation is perceived as uncontrollable, the person is judged not to be responsible, sympathy is experienced, and helping behavior is elicited.

We hypothesized that police officers would consider persons with schizophrenia to be less responsible for their situation than persons who were not described as having a mental illness. Accordingly, we also hypothesized that officers would feel more pity and express more willingness to help persons with a mental illness.

Two additional stereotypes about persons with mental illness were examined in this study—dangerousness and credibility. Dangerousness is perhaps the most pernicious stereotype about mental illness in the general population (19,20). Ruiz (21) suggested that the heightened sense of alert triggered by police dispatch codes in situations involving persons with mental illness may lead officers to inadvertently escalate situations through threatening body language and speech. We hypothesized that police officers would perceive a person with schizophrenia as being more dangerous than a person who was behaving in an identical manner but who was not identified as having schizophrenia.

People with mental illness are also often viewed as untrustworthy and unable to provide reliable information (22). Thus they are not considered to be reliable witnesses, and little is done on their behalf to resolve injustices (6). We hypothesized that officers would consider persons with mental illness to be less credible than persons who did not have a mental illness.

Methods

Police officers were recruited from those attending 30 in-service training courses randomly selected from a list of 150 available dates and classes offered by North East Multi Regional Training, Inc., over a ten-week data-collection period from March to June in 2002. The organization provides in-service training to law enforcement and corrections personnel throughout the metropolitan Chicago area.

Before the study, 12 vignettes describing situations involving a person with mental illness were developed after consultation with police officers from several departments and reviews of vignettes used in officer training manuals (6) and previous studies (15,23). Seventeen officers from a local police department then rated the 12 vignettes on the basis of believability and the amount of discretion the situation allowed. From these ratings, the best vignette for each type of situation was selected for the study. The vignettes described a hypothetical subject, Mr. S, in the role of a person in need of assistance, a victim, a witness, and a suspect. The vignettes are available from the authors.

The vignettes did not include descriptions of symptomatic behavior, because we were attempting to determine the impact of the label of schizophrenia on police attitudes and decisions. Had such descriptions been included, officers who were given the vignettes in which the person described was not labeled as having a mental illness may have adopted the label on their own. In addition, the vignettes portrayed intentionally minor infractions or disturbances. Presentation of serious violations of the law, injury, or acute symptoms would have risked limiting officers' discretion and variation in responses.

The consent process was conducted orally. Research staff explained that the study was about police attitudes and decisions; mental illness was not specifically mentioned. Police officers were randomly assigned one of eight survey versions—the four different roles of Mr. S (person in need of assistance, victim, witness, or suspect) by whether or not he was labeled as having schizophrenia. After reading the vignette, respondents were asked to complete a modified version of the Attribution Questionnaire (AQ) (20). The 31-item survey yielded five factors that corresponded with the attribution model. The responsibility factor reflects attributions about Mr. S's responsibility for his situation. The pity and anger factors reflect officers' affective reactions to Mr. S. The help factor represents officers' willingness to help Mr. S. The coercion factor represents officers' endorsement of legally mandating that Mr. S receive mental health treatment. We also measured officers' perceptions of Mr. S's dangerousness and the credibility of his account of the situation.

Results

Of the 548 surveys that were distributed at the training sessions, 382 were returned, for a response rate of 70 percent.

The mean±SD age of the police officers who responded was 34.8±7.7 years. Of the 362 officers who provided gender information, 41 (11 percent) were women. Of the 361 officers who provided information about their race, 309 (86 percent) were European American, 17 (5 percent) were African American, 18 (5 percent) were Latino, seven (2 percent) were Native American, five (1 percent) were Asian, and five (1 percent) described themselves as "other." A majority (343 respondents, or 95 percent) had at least some college education; 65 (18 percent) had an associate's degree, 151 (42 percent) had a bachelor's degree, and 34 (9.4 percent) had a graduate degree. The officers' mean length of service was 9.9±7.29 years. Although a majority of respondents were patrol officers (202 officers, or 53 percent), all other ranks were represented, including chief and deputy chief.

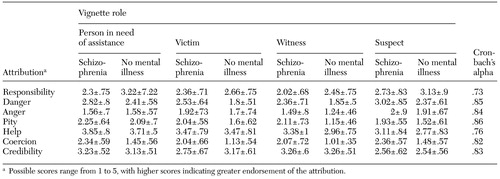

Means and standard deviations for the factors of the modified AQ (20) are listed in Table 1. Cronbach analyses of the subscales showed sufficient internal consistencies of .73 and above. Length of service was negatively correlated with perception of Mr. S as dangerous (r=-.122, p<.05). Education was positively correlated with anger toward Mr. S (r=.146, p<.001). Officers who described themselves as "better trained" rated Mr. S as being more responsible for the situation (r=.119, p.<.05) and reported feeling less pity for him (r=-.152, p<.001).

A 4 × 2 multivariate analysis of variance (vignette role by label) examined main and interaction effects on all subscales of the AQ. The results indicated significant main effects for label (F=30.275, df=9, 301, p<.001), vignette role (F=8.771, df=27, 909, p<.001), and the interaction between the two (F=1.783, df=27, 909, p<.01). Subsequent univariate analyses of variance indicated significant main effects for role (p<.05) on all seven subscales of the AQ and for label on all but the anger and credibility factors. Significant role-by-label interaction effects were found for the responsibility, pity, and credibility subscales.

Additional analysis suggested that persons who are known to have schizophrenia are viewed as being significantly less responsible than those whose mental health status is not known (F=35.736, df=1, 309, p<.001). The vignette role also had a main effect on responsibility attributions (F=11.135, df=3, 309, p<.001). Post hoc Tukey's honest significant difference (HSD) tests (p<.05) indicated that Mr. S was considered to be significantly more responsible in the role of a suspect than in the role of victim or a witness but not in the role of a person in need of assistance. A significant label-by-role interaction effect was observed (F=2.684, df=3, 309, p<.05).

The police officers in the sample reported feeling significantly more pity for a person who had been identified as having schizophrenia than for a person without a mental illness label (F=50.609, df=1, 309, p<.001). Vignette role also had a significant main effect (F=12.233, df=3, 309, p<.001). Post hoc Tukey's HSD tests indicated that the officers felt significantly more pity for a person in need of assistance than for a victim, a suspect, or a witness. A significant label-by-role interaction was observed (F=5.819, df=3, 309, p<.001). Although Mr. S received the most sympathy overall in the role of a person in need of assistance, the effect of the mental illness label was the smallest for this role. In contrast, the effect of the mental illness label for the role of witness was significantly larger.

No significant difference was noted in police officers' anger toward persons with and without the schizophrenia label. A significant main effect was observed for vignette role (F=9.902, df=3, 309, p<.001). Post hoc Tukey's HSD tests that were used to determine differences among roles indicated that officers felt significantly more anger toward Mr. S in the role of a suspect than in the role of a person in need of assistance or a witness and felt more anger toward him in the role of a victim than in the role of a witness. No significant interaction was found.

Police officers were significantly more willing to help a person identified as having schizophrenia than a person for whom no mental illness information was provided (F=5.939, df=1, 309, p<.05). Vignette role also had a significant effect (F=16.430, df=3, 309, p<.001). Post hoc Tukey's HSD tests that were used to identify differences among roles indicated that officers were significantly more willing to help a person in need of assistance than a victim, a witness, or a suspect and were significantly more likely to help a victim than a witness or a suspect. No significant interaction was found.

Persons with the schizophrenia label were considered significantly more dangerous than those without such a label (F=57.589, df=1, 309, p<.001). Vignette role also had a significant effect (F=15.667, df=3, 309, p<.001). Post hoc Tukey's HSD tests that were used to determine differences among roles indicated that officers perceived Mr. S as being significantly more dangerous when he was in the role of a suspect and a person in need of assistance than when he was in the role of a victim or a witness. No significant interaction was found.

The police officers were significantly more willing to endorse legal coercion to obtain treatment for a person with schizophrenia than for a person without the schizophrenia label (F=208.477, df=1, 309, p<.001). Vignette role also had a significant effect (F=9.610, df=3, 309, p<.001). Post hoc Tukey's HSD tests that were used to determine differences among roles indicated that officers were significantly more willing to coerce treatment for a person in need of assistance and a suspect than for a victim or a witness.

No significant difference was observed in credibility ratings between a person with and without a schizophrenia label. The role effect was significant (F=21.323, df=3, 309, p<.001). Post hoc Tukey's HSD tests indicated that Mr. S was considered significantly less credible in the role of a suspect than in the role of a victim, a person in need of assistance, or a witness. He was seen as significantly less credible in the role of a victim than in the role of a witness. The results suggest a significant label-by-role interaction (F=3.388, df=3, 309, p<.05). Interestingly, although Mr. S was considered more credible as a person in need of assistance if he was labeled as having schizophrenia, he was less credible as a victim, and the label had little effect on credibility for the other two roles.

Discussion

As we hypothesized, a person with schizophrenia was viewed by the police officers in this study as being less responsible, more deserving of pity, and more worthy of help than a person without a mental illness label. The mental illness label was associated with the greatest reduction in officers' perceptions of the person's responsibility for his situation when the person was described as someone in need of assistance. The study results did not support our hypothesis that officers would feel less anger toward a person with schizophrenia.

Our hypothesis that the schizophrenia label would increase perceived dangerousness was supported. When other variables were controlled for, the addition of information that the individual had schizophrenia significantly increased perceptions of violence across all role vignettes. This finding may be a reflection of officers' experiences on calls in which a person with mental illness did indeed become violent. Such incidents are often more memorable than are unproblematic calls. Unfortunately, if this heightened sense of risk causes officers to approach persons with mental illness more aggressively, they can escalate the situation and may evoke unnecessary violence (20). Support for coercion into treatment was low overall. Nevertheless, information that the person had schizophrenia significantly increased officers' willingness to endorse legally mandated treatment.

Our hypothesis about credibility was partially supported. Although there was not a main effect for the mental illness label, a significant interaction with vignette role was observed. The mental illness label had very little effect for role of suspect or witness. Perhaps the credibility of suspects is always questioned, regardless of their mental health status. The mental illness label was associated with greater perceived credibility of the person in need of assistance and with lower perceived credibility of the victim. The latter finding, although expected, is disturbing in light of evidence that persons with mental illness are particularly vulnerable to victimization (24,25). If they do seek assistance from the police, they may not be taken seriously or provided with the assistance they need (26). Of course, the situation of the victim as described in the vignette used in the study could be consistent with symptoms of schizophrenia—namely, paranoia and persecutory delusions. In light of their previous experiences with persons with mental illness, police officers may take complaints such as those presented in the vignette skeptically. Frustrating as the situation may be for police officers, it is imperative that they investigate such complaints from victims with mental illness before dismissing these individuals as "crazy."

This study has several limitations that should be mentioned. First, the police officers responded to written vignettes, not real-life situations. All attempts were made to create believable scenarios. However, the vignettes lacked the tangible context of street encounters. In reality, officers would have multiple sources of information—for example, the person's appearance, behavior, and location—on which to base judgments. In addition, the measures were self-reported and may reflect some social desirability bias. Although the results give us a preliminary look at police officers' attitudes and the outcomes they endorse, we cannot assume that their responses translate into behavior on the job. The officers' responses may have been quite different if we had provided a label of depression rather than schizophrenia or if the hypothetical person was a woman rather than a man. In addition, our findings may not be generalizable to officers from nonmetropolitan areas, whose work context may be significantly different.

Conclusions

Findings from this study suggest several issues that could be addressed in police policies and training. First, officers' tendency to question the credibility of persons with mental illness must be challenged. Certainly, symptoms of mental illness may cause individuals to perceive situations inaccurately, and officers may be wise to verify questionable information. However, to assume that a person who has mental illness is incapable of providing credible information could lead to the loss of valuable information and the neglect of persons who have been victimized.

Second, although persons with mental illness, particularly those who are experiencing particular psychotic symptoms and those who are abusing drugs and alcohol, have increased rates of violent behavior, most are not violent (27,28). At the same time, police officers must assume that all citizens they encounter might be dangerous, because the price of letting down their guard is too high. Unfortunately, exaggerated perceptions of dangerousness could lead to behaviors that escalate the situation. Addressing these perceptions through education and opportunities for positive contact with persons with mental illness who are stable in the community can improve their comfort in approaching a person with a mental illness. Skills training in the recognition of mental illness coupled with effective communication and deescalation strategies will assist officers in successfully resolving contacts with persons with mental illness who are in crisis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a research infrastructure support program grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (grant 5-R24-MH62198) to Dr. Corrigan. The authors thank Mike Bolton, Ph.D.

Dr. Watson and Dr. Corrigan are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the University of Chicago, 7230 Arbor Drive, Tinley Park, Illinois 60477 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Ottati is with the department of psychology of Loyola University in Chicago. A version of this paper was presented at the American Psychiatric Association's Institute on Psychiatric Services held October 9 to 13, 2002, in Chicago.

|

Table 1. Police officers' mean±SD scores on the modified Attribution Questionnaire in relation to a hypothetical person with or withouta schizophrenia label

1. Baird M, Berkowitz B: Training police as specialists in family crisis intervention: a community psychology action program. Community Mental Health Journal 3:315–317, 1967Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bonovitz JC, Bonovitz JS: Diversion of the mentally ill into the criminal justice system: the police intervention perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry 7:973–976, 1981Google Scholar

3. Engel RS, Silver E: Policing mentally disordered suspects: a reexamination of the criminalization hypothesis. Criminology 39:225–252, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Teplin L, Pruett N: Police as streetcorner psychiatrist: managing the mentally ill. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 15:139–156, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Deane MW, Steadman HJ, Borum R, et al: Emerging partnerships between mental health and law enforcement. Psychiatric Services 1:99–101, 1999Link, Google Scholar

6. National Council of State Governments: Criminal Justice Mental Health Consensus Project. Available at http://consensusproj ect.org, 2002Google Scholar

7. The Police Response to People With Mental Illness. Washington, DC, Police Executive Research Forum, 1997Google Scholar

8. Lamb H, Weinberger LE, DeCuir WJ: The police and mental health. Psychiatric Services 10:1266–1271, 2002Link, Google Scholar

9. Pescosolido BA, Monahan J, Link BG, et al: The public's view of the competence, dangerousness, and need for legal coercion of persons with mental health problems. American Journal of Public Health 9:1339–1345, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Socall DW, Holtgraves T: Attitudes toward the mentally ill: the effects of label and beliefs. Sociological Quarterly 3:435–445, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Pinfold V, Huxley P, Thornicroft G, et al: Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: evaluating an educational intervention with the police force in England. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38:337–334, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Corrigan PW, Lambert T, Sangster, et al: Experiences with discrimination by people with mental illness. Unpublished manuscript, 2002Google Scholar

13. Bittner E: Police discretion in emergency apprehension of mentally ill persons. Social Problems 14:278–292, 1967Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Kimhi R, Barak Y, Gutman J, et al: Police attitudes toward mental illness and psychiatric patients in Israel. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 4:625–630, 1998Google Scholar

15. Bolton MJ: The influence of individual characteristics of police officers and police organizations on perceptions of persons with mental illness. Virginia Commonwealth University, unpublished dissertation, 2000Google Scholar

16. Corrigan PW: Mental health stigma as social attribution: implications for research methods and attitude change. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice 1:48–67, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Weiner B: Judgments of responsibility: a foundation for a theory of social conduct. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

18. Schmidt G, Weiner B: An attribution-affect-action theory of behavior: replications of judgments of help-giving. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 3:610–621, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Link BG: Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review 1:96–112, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC, et al: An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, in pressGoogle Scholar

21. Ruiz J: An interactive analysis between uniformed law enforcement officers and the mentally ill. American Journal of Police 4:149–177, 1993Google Scholar

22. Stone D, Colella A: A model of factors affecting the treatment of disabled individuals in organizations. Academy of Management Review 2:352–401, 1996Google Scholar

23. Patch PC: Opinions about mental illness and disposition decision-making among police officers. Ph.D. dissertation. California School of Professional Psychology, 2001Google Scholar

24. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, et al: Criminal victimization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 1:62–68, 1999Link, Google Scholar

25. Marley J, Buila S: When violence happens to people with mental illness: disclosing victimization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 3:398–402, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

26. National Counsel of State Governments: Criminal Justice Mental Health Consensus Project. Available at http://consensusproject.org, 2002Google Scholar

27. Link BG, Monahan J, Stueve A, et al: Real in their consequences: a sociological approach to understanding the association between psychotic symptoms and violence. American Sociological Review 64:316–332, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393–401, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar