Stigma as a Barrier to Recovery: The Consequences of Stigma for the Self-Esteem of People With Mental Illnesses

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The objective of this study was to determine whether stigma affects the self-esteem of persons who have serious mental illnesses or whether stigma has few, if any, effects on self-esteem. METHODS: Self-esteem and two aspects of stigma, namely, perceptions of devaluation-discrimination and social withdrawal because of perceived rejection, were assessed among 70 members of a clubhouse program for people with mental illness at baseline and at follow-up six and 24 months later. RESULTS: The two measures of perceptions of stigma strongly predicted self-esteem at follow-up when baseline self-esteem, depressive symptoms, demographic characteristics, and diagnosis were controlled for. Participants whose scores on the measures of stigma were at the 90th percentile were seven to nine times as likely as those with scores at the 10th percentile to have low self-esteem at follow-up. CONCLUSIONS: The stigma associated with mental illness harms the self-esteem of many people who have serious mental illnesses. An important consequence of reducing stigma would be to improve the self-esteem of people who have mental illnesses.

One of the most tragic consequences of the stigma of mental illness is the possibility that it engenders a significant loss of self-esteem—specifically, that the stigma of mental illness leads a substantial proportion of people who develop such illnesses to conclude that they are failures or that they have little to be proud of.

Stigma can affect people through mechanisms of direct discrimination, such as a refusal to hire the person; structural discrimination, such as the availability of fewer resources for research and treatment; or social psychological processes that involve the stigmatized person's perceptions (1). In this study, we empirically examined the association between stigma and self-esteem by using a social psychological theory about stigma.

According to the stigma theory we used, people develop conceptions of mental illness early in life (2,3,4,5) from family lore, personal experience, peer relations, and the media's portrayal of people with mental illnesses (6,7,8,9,10). On the basis of these conceptions, people form expectations about whether most people will reject an individual who has a mental illness as a friend, an employee, a neighbor, or an intimate partner and whether most people will devalue a person who has a mental illness as being less trustworthy, less intelligent, and less competent.

For a person who never develops a serious mental illness and never experiences psychiatric hospitalization, these beliefs have little personal relevance. In sharp contrast, such beliefs have an especially poignant relevance for a person who develops a serious mental illness. If a person believes that others will devalue and reject people who have mental illnesses, that person must now fear that this possibility of rejection applies personally. The person may wonder, "Will others stereotype me, look down on me, and reject me because I have been identified as having a mental illness?"

A fear of rejection can have serious negative consequences. It is undoubtedly threatening and personally disheartening to believe that one has developed an illness that others are afraid of. Expecting and fearing rejection, people who have been hospitalized for a mental illness may act less confidently or more defensively, or they may simply avoid contact altogether. The result may be strained and uncomfortable social interactions with potential stigmatizers (11), more constricted social networks (3), poorer life satisfaction (12), unemployment, and loss of income (2,4). When performance is impaired in these ways, self-esteem is challenged, because the individuals affected may conclude that they are less able and less worthy than others.

But does the stigma of mental illness put people at risk of having low self-esteem? Some reports downplay the importance of stigma (13,14,15), indicating that it is "transitory and does not appear to pose a severe problem" (13) or that former patients "enjoy nearly total acceptance in all but the most intimate relationships" (14). If stigma is really inconsequential, one would expect it to have little—if any—impact on self-esteem. From such a vantage point, any observed association between stigma and self-esteem would be suspect—the product of biased perception through which people with low self-esteem view the world around them, including stigmatization by others, in a negative and pessimistic light. According to this view, it is not so much that stigma influences self-esteem but rather that self-esteem shapes one's perceptions of and responses to the experience of stigma. Given this alternative view, the existence and magnitude of any connection between stigma and self-esteem, along with an explanation for this connection, are all in question.

We found only one empirical study that directly examined the connection between stigma and the self-esteem of people who develop mental illnesses (16). It showed that stigma led to self-deprecation, which in turn compromised feelings of mastery over life circumstances. Previous research on attributes other than mental illness has found that although stigmatized groups often experience lower self-esteem, this is not always the case (17). Strong skepticism about the importance of the stigma of mental illness and the fact that relatively little research has been conducted on the connection between stigma and self-esteem indicate the need for more research in this area.

Methods

Setting

Our study was conducted between 1995 and 1997 in a clubhouse program modeled on the Fountain House prototype (18). Club members were recruited by invitation to participate in the study, and 88 members agreed to be randomly assigned to one of two conditions: an intervention designed to facilitate coping with stigma and a no-intervention control group. Members who were assigned to the control group were offered the intervention after a six-month follow-up assessment. The intervention had no measurable effect on participants' perceptions of stigma, depressive symptoms, or self-esteem (19).

Approval for the study was obtained from the New York State Psychiatric Institute's institutional review board. We report data for 70 of the 88 persons who were recruited at baseline, who had valid stigma and self-esteem measures at six-month follow-up.

The mean±SD age of these 70 participants was 41.3±10.7 years, and most (45, or 64 percent) were male. Fifty-nine (84 percent) were white, eight (11 percent) were African American, and three (4 percent) were members of other racial or ethnic groups. Twelve (17 percent) had less than a high school education, 46 (66 percent) had completed high school but had not graduated from college, and 12 (17 percent) were college graduates. The median number of hospitalizations that study participants experienced was five, with a range of none to 50. The most common diagnosis was schizophrenia (25 patients, or 36 percent), followed by other nonaffective psychotic disorders (11 patients, or 16 percent), depressive disorder (six patients, or 9 percent), bipolar disorder (five patients, or 7 percent), and other (23 patients, or 33 percent).

Of the initial 88 persons, 70 (80 percent) and 55 (63 percent) were reinterviewed at the six- and 24-month follow-ups, respectively. In comparing the patients who were lost to follow-up with those who were reinterviewed, we found no significant differences in age, sex, marital status, education, diagnosis, baseline depressive symptoms, baseline stigma, or baseline self-esteem at either the six- or 24-month follow-up.

Measures

Self-esteem. We used a version of Rosenberg's scale to measure self-esteem (20). Study participants were asked whether they strongly agreed, agreed, disagreed, or strongly disagreed with ten statements such as "At times, you think you are no good at all." Each item was coded so that a high score on the item reflected high self-esteem. The items were then summed and divided by ten to create a self-esteem scale score. The reliability of the scale was .85 at baseline, .83 at six months, and .87 at 24 months.

Stigma. Perceived devaluation-discrimination was measured with a 12-item instrument that asks about the extent of agreement with statements indicating that most people devalue current or former psychiatric patients by perceiving them as failures, as less intelligent than other persons, and as individuals whose opinions need not be taken seriously (4,21). The measure captures a key ingredient of our stigma theory—the extent to which a person believes that other people will devalue or discriminate against someone with a mental illness. The scale is balanced such that a high level of perceived devaluation-discrimination is indicated by agreement with six of the items and by disagreement with six others. Items are appropriately recoded so that a high score reflects a strong perception of devaluation-discrimination. The scale is constructed by summing the items and dividing by 12 to produce a scale score that varies from 1 to 4. The reliability of the scale was .88, .86, and .88 at baseline and at the six- and 24-month follow-ups, respectively.

Stigma-withdrawal (18) was used to assess a key component of our stigma theory by quantifying the extent to which participants endorse withdrawal as a way to avoid rejection. Our nine-item instrument assesses the degree of agreement with statements such as "If a person thought less of you because you had been in psychiatric treatment, you would avoid him or her." All items are scored so that a high score indicates a high level of stigma-withdrawal. The item scores are summed and divided by nine to produce a score that varies from 1 to 4. The reliability of the scale was .70, .69, and .70 at baseline and at the six- and 24-month follow-ups, respectively.

Although the stigma scales are conceptually distinct, the Pearson correlation between them was .45 at baseline. Respondents who believed that current and former psychiatric patients are devalued and discriminated against were also likely to endorse withdrawal as a way of coping with the possibility of rejection. Consequently, we examined both the combined effects and the unique effects on self-esteem of these two measures.

Control variables. In addition to the standard demographic variables of age, education, and sex (male=1, female=0), we also controlled for random assignment to the experimental group (coded as 1) versus the control group (coded as 0), diagnosis (schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychotic disorders=1, other diagnoses= 0), and baseline depressive symptoms. We measured depressive symptoms with a shortened 14-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (alpha=.83), a self-report measure that asks a person how often during the previous week he or she experienced each symptom. Possible scores on this scale range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating a greater number of and more frequently experienced depressive symptoms.

Analysis

We present descriptive results to illustrate levels of self-esteem and stigma experienced by the study participants. We used regression analysis to test hypotheses about the effects of stigma on self-esteem in our longitudinal design. The analyses included only the control variables that were predictive of at least one of the outcome variables of interest—stigma or self-esteem. Finally, we tested for the consistency of the effect of stigma on self-esteem across groups defined by age, sex, education, diagnosis, and depressive symptoms by assessing evidence for interactions between these variables and stigma.

Results

Descriptive results for self-esteem and stigma

Baseline responses to items in the self-esteem scale indicated that low self-esteem was a significant problem for a substantial minority of study participants. For example, 38 participants (54 percent) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement "You feel useless at times," and 26 (37 percent) agreed or strongly agreed with "All in all, you are inclined to feel that you are a failure." In comparison, a study of a nationally representative sample of the general U.S. population (N= 487) used the same questions and showed that 29 percent felt useless at times and 10 percent felt that they were failures (22). The mean±SD score on the ten-item self-esteem scale was 2.7±.47, significantly higher than the midpoint of 2.5, indicating that, on average, participants expressed positive self-esteem (t=3.76, df=69, p<.05). Nevertheless, a substantial minority (17 patients, or 24 percent) had scores below the midpoint, and most participants (51, or 73 percent) indicated low self-esteem on two or more items.

Baseline responses to the measure of perceived devaluation-discrimination indicated that most study participants believed that current and former psychiatric patients experience rejection. When participants who agreed and those who strongly agreed were grouped together, 52 (74 percent) expressed a belief that employers will discriminate against former psychiatric patients; 57 (81 percent) and 46 (66 percent) had similar expectations about dating relationships and close friendships, respectively; 48 (69 percent) expressed a belief that former psychiatric patients will be seen as less trustworthy, 41 (59 percent) that they will be seen as less intelligent, and 47 (67 percent) that their opinions will be taken less seriously. The mean±SD score on the 12-item scale was 2.76±.50, which is significantly above the midpoint of 2.5, indicating that most study participants believed that psychiatric patients will face rejection in numerous ways (t=4.34, df=69, p<.001).

The results also indicate that study participants endorsed withdrawal as a means of coping with the possibility of rejection. When the participants who agreed and those who strongly agreed were grouped together, 44 (63 percent) indicated they would avoid a person if they believed that person thought less of them because they had received psychiatric treatment, 47 (67 percent) indicated that they found it easier to be friendly with people who had been psychiatric patients, and 50 (71 percent) indicated that people with serious mental illnesses will find it less stressful to socialize with other people who have a serious mental illness. The mean±SD score on the nine-item scale was 2.82±.42, significantly above the midpoint of 2.5, indicating that most study participants endorsed stigma-withdrawal (t=7.07, df=69, p<.001).

Self-esteem and perceived stigma

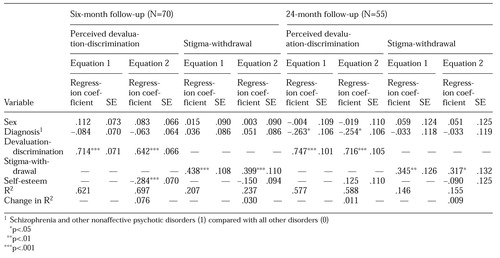

Table 1 presents the results of regression analyses indicating the importance of self-esteem in determining perceptions of stigma. Baseline self-esteem uniquely explained 7.6 percent of the variance in perceived devaluation-discrimination at six months. No significant effects of self-esteem on stigma-withdrawal at either follow-up point were observed, and no significant effect of self-esteem on perceived devaluation-discrimination was observed at 24-month follow-up. This latter finding is important in that it suggests that the effect of self-esteem on perceived devaluation-discrimination at six months had eroded by 24 months.

Stigma and self-esteem

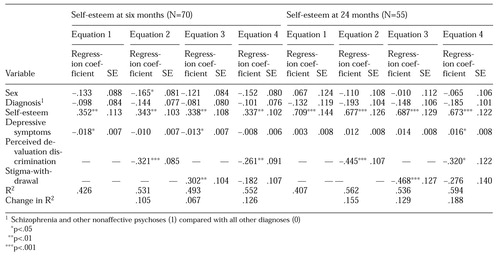

Table 2 presents the results of regression analyses indicating the importance of stigma in determining self-esteem. Four regression equations are shown for each of the two follow-up periods. In the first equation, baseline self-esteem, sex, diagnosis, and depressive symptoms were entered as predictors of self-esteem at follow-up. In equations 2 and 3, each of the stigma variables was added separately. In equation 4, the two stigma variables were added together to allow their combined effects on self-esteem to be determined. As equations 2 and 3 show, both perceived devaluation-discrimination and stigma-withdrawal were significantly associated with self-esteem at each follow-up point. Beyond the variance accounted for by the other variables, the two stigma variables, taken together, explained 12.6 percent of the variance in self-esteem at six months and 18.8 percent at 24 months.

To provide an alternative indicator of the strength of the connection between stigma and self-esteem, we dichotomized the self-esteem scale at its midpoint (2.5) and used logistic regression to calculate the odds that stigma was associated with low self-esteem. When baseline self-esteem, sex, and diagnosis were controlled for, a person who had a score at the 90th percentile on the devaluation-discrimination scale was estimated to be 8.8 times as likely to have low self-esteem at follow-up as a person who had a score at the tenth percentile. A similar comparison for stigma-withdrawal indicated that a person who had a score at the 90th percentile was seven times as likely to have low self-esteem at follow up as a person who had a score at the tenth percentile.

We also tested for interactions between the stigma variables and age, sex, diagnosis, and depressive symptoms. Only one interaction was significant, and, given that we tested 16, this one may have occurred by chance. We conclude that the baseline stigma measures were consistently related to self-esteem at follow-up and that the magnitude of the effect was relatively constant across subgroups of the sample.

Discussion

Some people have theorized that stigma is harmful to the self-esteem of persons who have mental illnesses. Others have claimed that the stigma of mental illness is relatively inconsequential and should therefore play only a very small role—if any—in shaping the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Our results sharply contradict the latter claim. Baseline measures of perceived devaluation-discrimination and stigma-withdrawal strongly predicted self-esteem at both the six- and the 24-month follow-up, even with adjustment for baseline self-esteem and depressive symptoms.

Our study had some potential limitations. Participants' symptomatic states or personality orientations may have influenced their reports of perceptions of stigma. For example, if a person was so depressed that all his or her perceptions were colored in a negative way, that person might have reported both low self-esteem and stigma without there being any causal relation between the two. Two considerations lead us to question this possibility. First, controlling for baseline self-esteem sharply reduced the possibility of contamination. This control removed from the perception of stigma at baseline all sources of correlation that were due to baseline self-esteem, including any correlation due to contaminated measurement. Second, the effect of stigma remained robust when we controlled for depressive symptoms, which is contrary to the hypothesis that depressive symptoms colored perceptions to produce an artifactual association between stigma and self-esteem. Taken together, this evidence makes it unlikely that contaminated measurement accounts for our results.

It is also possible that some unmeasured confounding variable accounted for the association between stigma and self-esteem. However, the longitudinal associations between stigma and self-esteem were very strong. As a result, any unmeasured confounder would need to have very strong associations with both the stigma measures and self-esteem in order to reduce the associations between these variables to the null value. Given that we controlled several potential confounding variables that accounted for substantial proportions of variance in self-esteem at follow-up—for example, baseline self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and diagnosis—it is highly unlikely that some heretofore unspecified confounder would have sufficiently strong associations with both baseline stigma and follow-up self-esteem to render their strong association spurious.

Because we tested our theory in a clubhouse for persons with severe mental illness, the results are generalizable only to similar populations. Nevertheless, stigma was both consistently related to self-esteem and relatively constant in the magnitude of its effects across subgroups of the sample defined by age, sex, diagnosis, and depressive symptoms. Although the generalizability of the effect in our sample does not prove that it is also generalizable to other populations, it does raise our confidence that the effect is not limited to a particular subgroup. On the contrary, our results suggest that the effect of stigma on self-esteem was present in very diverse subgroups of the sample we studied.

Conclusions

The results of this study contribute to our understanding of the role that stigma plays in the lives of people who have mental illnesses, in several ways. First, contrary to the claim that stigma is relatively inconsequential, our results suggest that stigma strongly influences the self-esteem of people who have mental illness. Second, we used a social-psychological theory that identified and tested one important mechanism through which stigma affects people. Because stigma can affect people through many different mechanisms (1), it is important to identify exactly what those mechanisms are so that effective interventions can be developed.

Third, although the existence of a connection between stigma and self-esteem may not be surprising to some readers, the magnitude of the association that we uncovered is startling and disturbing. As our results show, a person who strongly endorsed the two stigma scales was seven to nine times as likely to have low self-esteem at follow-up as a person who had a low score on these scales. The strength of this association highlights the importance of stigma in the lives of people who have mental illness and indicates why it is critical for mental health research and policy to address stigma with fervor.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a senior investigator award to Dr. Link and Dr. Struening from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders.

Dr. Link and Dr. Struening are affiliated with the Mailman School of Public Health of Columbia University in New York City and with the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Ms. Neese-Todd is with the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in New Brunswick. Ms. Asmussen is with the Beginning With Children Foundation in New York City. Dr. Phelan is with the Mailman School of Public Health of Columbia University. Send correspondence to Dr. Link at Epidemiology of Mental Disorders, 100 Haven Avenue, Apartment 31D, New York, New York 10032 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper is part of a special section on stigma as a barrier to recovery from mental illness.

|

Table 1. Results of regression analyses of baseline self-esteem on stigma variables at six- and 24-month follow-up among members of a clubhouse program for persons with mental illness

|

Table 2. Results of regression analyses of baseline stigma variables on self-esteem at six- and 24-month follow-up among members of a clubhouse program for persons with mental illness

1. Link BG, Phelan JC: Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology 27:363-385, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Link BG: Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review 52:96-112, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, et al: A modified labeling theory approach in the area of mental disorders: an empirical assessment. American Sociological Review 54:100-123, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Link BG: Mental patient status, work, and income: an examination of the effects of a psychiatric label. American Sociological Review 47:202-215, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, et al: On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38:177-190, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wahl OF: Media Madness: Public Images of Mental Illness. New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 1995Google Scholar

7. Scheff TJ: Being Mentally Ill: A Sociological Theory. Chicago, Aldine de Gruyter, 1966Google Scholar

8. Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H: The effect of violent attacks by schizophrenic persons on the attitude of the public towards the mentally ill. Social Science and Medicine 43:1721-1728, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Furnham A, Bower P: A comparison of academic and lay theories of schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 161:201-210, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Angermeyer M, Matschinger H: Lay beliefs about schizophrenic disorder: the results of a population study in Germany. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:39-45, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Farina A, Felner RD: Employment interviewer reactions to former mental patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 82:268-272, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Rosenfield S: Labeling mental illness: the effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. American Sociological Review 62:660-672, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Gove WR: The current status of the labeling theory of mental illness, in Deviance and Mental Illness. Edited by Gove WR. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1982Google Scholar

14. Crocetti G, Spiro H, Siassi I: Contemporary Attitudes Towards Mental Illness. Pittsburgh, Pa, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1974Google Scholar

15. Aubry T, Tefft B, Currie R: Public attitudes and intentions regarding tenants of community mental health residences who are neighbours. Community Mental Health Journal 31:39-52, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wright ER, Gronfein WP, Owens TJ: Deinstitutionalization, social rejection, and the self-esteem of former mental patients. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41:68-90, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Crocker J: Social stigma and self-esteem: situational construction of self-worth. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 35:89-107, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Beard J: The rehabilitation services of Fountain House, in Alternatives to Mental Hospital Treatment. Edited by Stein LI, Test MA. New York, Plenum, 1978Google Scholar

19. Link BG, Struening E, Neese-Todd S, et al: A clubhouse-based intervention designed to address the stigma of mental illness. New York, Columbia University, in pressGoogle Scholar

20. Rosenberg M: Conceiving the Self. New York, Basic Books, 1979Google Scholar

21. Link BG, Mirotznik J, Cullen FT: The effectiveness of stigma coping orientations: can negative consequences of mental illness labeling be avoided? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 32:302-320, 1991Google Scholar

22. Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, et al: Lifetime and five-year prevalence of homelessness in the United States: new evidence of an old debate. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:347-354, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar