Racial Preferences for Participation in a Depression Prevention Trial Involving Problem-Solving Therapy

African Americans have been designated a high-risk population for inadequate depression care. Conducting treatment trials with this population is important because finding racial differences in treatment response would suggest that culturally concordant approaches are needed. One issue that could account for disparities in care is inadequate access to care. It has been claimed that individuals from racial minority groups are reluctant to enroll in research interventions ( 1 ). Wendler and colleagues ( 1 ), however, recently identified 20 clinical trials with over 70,000 participants with minimal differences in recruitment rates for African Americans and Caucasians. Their analyses of mental health trials included participants with a diagnosis of substance abuse or schizophrenia. Another trial involving integrated mental health and primary care, the IMPACT (Improving Mood: Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment) study, enrolled participants with either major depression or dysthymia; in that trial the rate of African-American participation was also no different from that of Caucasians ( 2 ). In this study, we compared rates of consent between African Americans and Caucasians approached for an indicated prevention intervention involving problem-solving therapy in primary care. This intervention included individuals with subsyndromal depression, thus offering a unique population not yet examined. Our first hypothesis stated that there would be no racial differences in consent rates to participate in the intervention.

Cruz and colleagues ( 3 ) noted that dysfunctional coping strategies could be another factor accounting for treatment disparities among African Americans with depression. We hypothesized that coping skills to solve social problems may differ by race and lead to disparities. A racial difference could be important for developing treatment trials for primary care problem-solving therapy because depression is associated with problem-solving deficits. The therapy focuses on improving these skills; finding a racial difference would suggest that specialized treatment approaches are needed ( 4 ).

Hill-Briggs and colleagues ( 4 ) examined problem solving in a group of African Americans with diabetes who had Centers for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scores of at least 11 out of 60 (with higher scores indicating worse depression symptoms). Eighty-five percent had average or higher Social Problem Solving Inventory (SPSI) scores (≥86). However, the authors did not examine these scores with other racial groups. We are not aware of any studies that have compared SPSI scores by race among individuals with subsyndromal depression. Thus, with participants in our primary care problem-solving therapy intervention, we tested a second hypothesis, that social problem-solving coping skills would be lower among African Americans than Caucasians.

Methods

Participants were recruited for this trial, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, to determine the ability of primary care problem-solving therapy to prevent major depression among persons with subsyndromal depression. As a control, some participants received dietary education in lieu of the problem-solving therapy. The data represent a baseline analysis from the trial, which was conducted between August 24, 2006, and January 15, 2009. Potential participants were initially screened with a waiver of informed consent and waiver of documentation of informed consent from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB). All individuals who agreed to participate signed an IRB-approved informed consent statement.

Participants were aged 50 or older and had CES-D scores or 11 or higher ( 5 ). Individuals were excluded if they had major depression, active substance abuse or dependence, or a combination of these conditions in the past year, if they were currently on antidepressant therapy, or if they had a Mini-Mental Status Examination score below 24. We compared the proportion of African-American and Caucasian participants who signed informed consent forms. Among those who consented, we also examined problem-solving skills by administering the SPSI ( 6 ), a 25-item self-report measure that rates problem-solving orientation and problem-solving skills. Primary care problem-solving therapy addresses items assessed with the SPSI: problem definition and formulation, generation of alternative solutions, decision making, and solution implementation and verification. Items 4, 5, 9, 13, and 15 from the SPSI constitute the problem orientation subscale (PPOS). Also administered was the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-17) ( 7 ).

Continuous variables were assessed for normality and homogeneity of variance. The descriptive statistics used to characterize the two groups included means and standard deviations or percentages. Inferential statistics tested our hypotheses at alpha <.05.

Results

To test our first hypothesis, self-identified racial status was obtained for 2,788 potential participants referred from primary care and community-based health clinics in the Pittsburgh area; 1,970 (71%) were Caucasians and 818 (29%) were African Americans. The proportion of African Americans in our sample (29%) was similar to the percentage of African Americans in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area (27%) ( www.idcide.com/lists/pa/on-population-african-american-percentage.htm ). Eighty-two Caucasians (4%) and 46 (6%) African Americans signed consent forms; this difference was not significant. Of the 1,888 Caucasians who did not participate, 683 (36%) refused; of the 722 African Americans who did not participate, 99 (14%) refused.

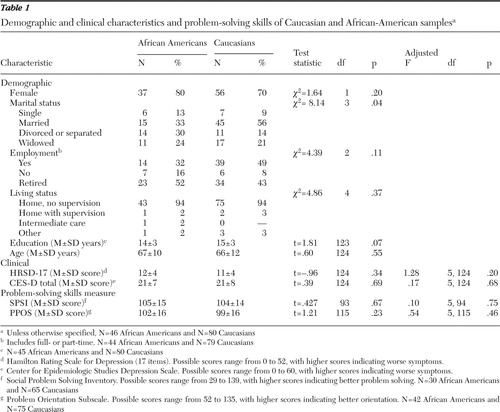

Group demographic characteristics are provided in Table 1 for 46 of the African-American and 80 of the Caucasian participants; data from two of the Caucasians who consented but did not have either CES-D or HRSD-17 scores were not included in this analysis. The only significant difference between groups was with respect to marital status, and all further assessments controlled for this. We determined that there were no significant racial differences in HRSD-17, CES-D, SPSI, or PPOS scores ( Table 1 ). Also, there was a significant negative association of HRSD-17 scores with SPSI scores among Caucasians (r=-.34, p<.01; N=65); among African Americans, there was a nonsignificant negative association for this comparison of these scores. For PPOS scores there were significant negative associations with HRSD-17 scores of Caucasian participants (r=-.42, p<.01; N=75) and African-American participants (r=-.42, p<.01; N=42). Finally, tests of the homogeneity of correlation revealed no significant racial differences with regard to the relationship between HRSD-17 score and either SPSI or PPOS score.

|

Discussion and conclusions

Our analyses indicate that African Americans and Caucasians had comparable rates of willingness to participate in a trial examining whether primary care problem-solving therapy is an effective intervention for depression. The findings are consistent with those of Wendler and colleagues ( 1 ), who demonstrated that African-American recruitment in numerous trials, including several mental health trials, was not lower than that of Caucasians. Likewise, the IMPACT study demonstrated that African Americans were not any less willing than Caucasians to enter a psychosocially oriented intervention for treating patients who had major depression or dysthymia ( 2 ). In addition, the PROSPECT (Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial) study, which used interpersonal psychotherapy in combination with medication management in treating patients with major depression or other subsyndromal depressive syndromes, had a 25% rate of African-American participation and no racial differences in dropouts or response rates ( 8 ). Our study is unique in that it examined a sample of individuals who were only subsyndromally depressed.

Differences in coping styles between Caucasians and African Americans may be one factor that could account for disparities in treatment ( 5 ). Indeed, there is a strong link between spiritual and psychological well-being for many African Americans. Prayer is an important coping strategy. According to Cooper and colleagues ( 9 ), African Americans are more likely than Caucasians to rate "having faith in God," "being able to ask God for forgiveness," and prayer as important aspects of depression care. In addition, the literature suggests that depressed African Americans have a greater tendency to seek help from their own social milieu, such as family, friends, and clergy ( 10 ).

In addition to these known differences in preferred coping styles, our findings suggest that African Americans and Caucasians have similar problem-solving skills; likewise, there were no racial differences with regard to the negative associations between social problem-solving skills and depressive symptoms. Thus, in both groups, participants with the more severe depressive symptoms appeared to exhibit greater deficits in problem-solving skills. Furthermore, it appears that depressed individuals in both racial groups may benefit from the specific primary care problem-solving process described.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported primarily by grant P60-MD000107 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities and by grants P30-MH71944, NIMH 6398-01, and 2P60-MD000207-07 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al: Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Medicine 3:e19, 2006Google Scholar

2. Arean P, Hegel M, Vannoy S, et al: Effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for older, primary care patients with depression: results from the IMPACT project. Gerontologist 48:311–323, 2008Google Scholar

3. Cruz M, Pincus HA, Harman JS, et al: Barriers to care-seeking for depressed African Americans. International Journal of Psychiatry and Medicine 38:71–80, 2008Google Scholar

4. Hill-Briggs F, Gary TL, Yeh HC, et al: Association of social problem solving with glycemic control in a sample of urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 29:69–78, 2006. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16397820 Google Scholar

5. Radloff L: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385–401, 1977Google Scholar

6. Bell AC, D'Zurilla T: Problem solving therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Reviews 29:348–353, 2009Google Scholar

7. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 23:56–62, 1960Google Scholar

8. Bruce ML, Ten Have T, Reynolds CF, et al: Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized control trial. JAMA 291:1081–1091, 2004Google Scholar

9. Cooper LA, Brown C, Vu HT, et al: How important is intrinsic spirituality in depression care? A comparison of white and African-American primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16:634–638, 2001Google Scholar

10. Brown C, Abe-Kim JS, Barrio C, et al: Depression in ethnically diverse women: implications for treatment in primary care settings. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 34:10–19, 2003Google Scholar