Responsibility and Choice in Addiction

Abstract

The treatment of patients with substance use disorders requires that providers be aware of their own views on the relative roles of personal responsibility and of forces outside personal control in the onset and progression of and recovery from these disorders. The authors review the role of responsibility for addiction from several viewpoints: biological, psychological, sociocultural, self-help, religious, and forensic. Factors that affect personal responsibility in addictive diseases include awareness of the problem, knowledge of a genetic predisposition, understanding of addictive processes, comorbid psychiatric or medical conditions, adequacy of the support network, nature of the early environment, degree of tolerance of substance abuse in the sociocultural context, and the availability of competent psychiatric, medical, and chemical dependency treatment. Factors that affect societal responsibility include degree of access to illicit drugs, society's level of tolerance of drug use, the courts' approach to deterring substance abuse (punishment versus treatment), individuals' refusal to obtain substance abuse treatment, presence of clear behavioral norms, availability of early assessment and prevention, presence of community education, and degree of access to outpatient and community treatment.

For most of modern history, the excessive use of alcohol or drugs has been considered controllable behavior. Those who abused these substances were viewed as exercising their free will and choosing not to limit or control this behavior. Society therefore tended to blame and punish offending individuals rather than to understand the processes that contribute to addiction or strategies for rehabilitation. In this paper, we revisit the question of responsibility and choice in addiction and document the continuing emphasis on free will or personal choice, particularly as found in religious organizations, self-help programs, and forensic contexts. In contrast, psychological, cultural, and, more recently, biological perspectives offer appreciation for cognitive and behavioral processes that subvert or at least compromise the capacity for personal choice.

The tension between these contrapuntal themes is likely to intensify as our society witnesses continuing endemic substance abuse and experiences frustration with its consequences—crime, family discord, impaired work productivity, and health costs. The biological underpinnings of the cognitive and behavioral changes that occur among persons with substance use disorders are being explicated, and these findings are leading to improved treatment.

We are not suggesting that the ambivalence about addictions is new. As early as the colonial era in America, Dr. Benjamin Rush, the nation's acknowledged first psychiatrist and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, formulated alcoholism as an "odious disease." Nevertheless, the full embrace of this concept by American medicine was an exceedingly slow process, and it was not until 1967 that the American Medical Association officially classified alcoholism as a disease (1). However, we believe that the tensions between the polar viewpoints of determinism and free will are growing and will force our society to rethink the challenges of such a dichotomy.

This article summarizes biological, psychological, social and cultural, self-help, religious, and forensic perspectives on personal responsibility for substance abuse and addiction. The purpose of this summary is to encourage clinicians who treat patients with substance use disorders to examine their own views about the roles of personal choice and determinative forces in the onset and progression of and recovery from substance use disorders.

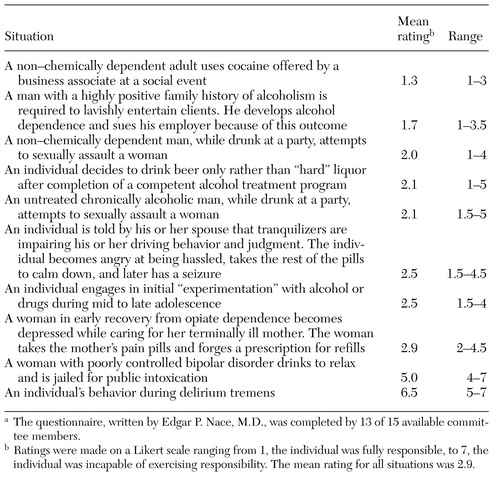

The article summarizes the work of the 16-member committee on addictions of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry. The committee was created in 1985 and was charged with the task of reviewing emerging issues in addiction treatment. In the spirit of this paper—which is to encourage clinicians to examine their views—the committee members examined their own views on the topic of personal responsibility for substance abuse and addiction by anonymously rating ten hypothetical situations involving substance use. The results are listed in Table 1.

Biological underpinnings of addiction

The role of biological factors in addiction is supported by increasingly compelling evidence. Abusable substances act on the reward systems of the brain to produce a reinforcing experience. In discussions of the neural mechanisms of drug reinforcement, Koob (2) emphasized the role of the median forebrain bundle and its connections with the basal forebrain, especially the nucleus accumbens, and the role of dopaminergic systems in the reinforcing properties of cocaine, opiates, cannabis, nicotine, and alcohol. In addition, serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and opioid peptides are involved in the rewarding effects of alcohol. Abusable substances act on dopaminergic fibers to produce their reward-enhancing effects, with different classes of drugs having different sites of specific action. Addiction is understood to be mediated by the same neurotransmitter mechanisms that are involved in many other mental illnesses. The mapping of the human genome will enable scientists to conduct more precise research to examine the genetics of addiction. This knowledge will improve our understanding of the initiation and maintenance of problematic substance use and the difficulty patients often experience in adhering to treatment.

Certain individuals seem more vulnerable to developing alcoholism because of their genetic background. Human studies examining such genetic vulnerability have focused on "trait" markers—for example, diminished sensitivity to ethanol (3), decreased P-300 amplitude of event-related potentials in sons of alcoholics (4), and diminished adenylyl cyclase activity (5). Chronic exposure to alcohol and other drugs appears to have significant effects on the regulation of gene expression (6). Rodent strains bred for different sensitivities to various alcohol dependence traits, such as ethanol preference and response, have shown neurobiological differences. For example, the functioning of the brain reward system in Lewis rats, which self-administer opiates, cocaine, and alcohol at high rates, differs from that in Fischer 344 rats, which self-administer at much lower rates (7).

Extended or excessive use of some addictive substances, notably alcohol, may result in permanent cognitive deficits that interfere with treatment planning, insight, and impulse control. These cognitive deficits are frequently mislabeled as denial. In the gradation between determinism and free will, the initiation of substance use may occur toward the free-will end of the spectrum, whereas continued abuse may fall more toward the deterministic end, after certain neurochemical changes have taken place in the brain. Once the addictive process begins, neurobiological mechanisms make it increasingly difficult for the individual to abstain from the drug. These findings have important implications for the personal responsibility of the addicted individual (8).

Psychological perspectives

Two crucial psychological issues are the individual's responsibility for having an addiction and the individual's responsibility for obtaining treatment. Factors that augment and diminish personal responsibility are listed in the box on the next page. Control is vital to the concept of responsibility. The responsibility for creating or solving a problem hinges on the degree of control that one is able to exert over the situation or over future events. No one has control over his or her genetic makeup or childhood environment, both of which are important in the formation of addictive disorders. A child is not responsible for being raised in a dysfunctional home by two alcoholic parents. However, he or she is responsible for attempting to correct the sequelae of the trauma, once he or she is old enough to be aware of and able to understand the problems.

Factors that influence the degree of personal responsibility in addictive disorders

Factors that augment personal responsibility

Awareness of the problem

Knowledge of a genetic predisposition

Understanding of addictive processes

Adequate support network

Availability of competent chemical dependency treatment

Availability of psychiatric and medical treatment

Factors that diminish personal responsibility

Comorbid psychiatric or medical conditions

Genetic predisposition

Adverse early environmental factors

Social or cultural dissonance (tolerance of deviant substance use or abuse)

Iatrogenic addiction (for example, by adhering to a drug regimen prescribed by a physician)

In addition, one might not have control over the ability to recognize the presence of certain disorders, especially those characterized by a lack of insight, such as dementia, mania, and schizophrenia. Society can hardly blame individuals for having disorders whose inception is beyond their control, nor can it assign blame to those who fail to seek treatment for disorders of which they are unaware. If the disorder itself impairs one's capacity for making rational decisions, as addictions sometimes do, then the capacity for adhering to treatment may also be diminished.

The initiation of alcohol or drug use follows the principles of socially learned behavior: an antecedent condition (for example, availability of a substance, permission to use the substance, or peer pressure to use the substance) is followed by a choice (use) and a consequence (approval or euphoria, for example). For some individuals, this social learning paradigm is supplanted by what seems to be "driven" behavior based on an induced appetite for drugs or alcohol—an appetite as powerful in some as the natural appetite of hunger. This process renders the individual susceptible to multiple internal and external cues that, through conditioning, trigger the appetitive behavior (use of drugs in the case of addictions) (9). For example, the person may turn to alcohol or drugs when exposed to a cue such as entering a tavern or experiencing a mood state associated with previous use.

These psychological mechanisms generally are not apparent to the addicted person, and this lack of awareness undermines the ability to act responsibly and limit substance-seeking behavior. However, these mechanisms are amenable to modification through treatment. One can become conscious of the conditioned cues and learn to circumvent them (10).

Some clinicians espouse the self-medication hypothesis, drug use is seen as a defense against intense or intolerable affect (11,12,13,14). For instance, opiate use may represent a defense against borderline psychopathology, such as fear of disorganization. As ego strengthening occurs through psychotherapeutic or pharmacological treatment or both, the individual may have less need to self-medicate to control emotional distress and pain.

Prochaska and colleagues (15) have outlined several stages through which addicted people pass before being fully able to take action to stop using a drug of abuse (15). While in the precontemplation stage, in which they are not considering a change in behavior, they may be unaware of problems associated with the drug use and are not psychologically prepared to undertake the steps necessary to put an end to their addictive behaviors. At this stage, they are not open to straightforward treatment initiatives, and their ability to assume a responsible stance in changing their drug-using behavior is still limited. During subsequent stages, they achieve a greater degree of awareness and readiness to assume responsibility for undertaking appropriate efforts to control the addictive behaviors. As the substance abuser moves through each successive stage, the capacity to assume responsibility for the addictive behaviors increases.

Sociological and cultural perspectives

Social and cultural factors, pervasive but seldom perceived by the members of a given society, influence the expression of and response to addiction. A society's norms may be discerned in how it deals with aberrant behavior resulting from substance abuse (16). The variety of ways a society can view such behavior is limited. Examples include considering the individual responsible for acts committed while intoxicated, reducing blame for offenses a person commits under the influence, or excusing the deviant or problematic behavior of persons who are intoxicated—for example, by considering intoxication at social gatherings a "time out" during which stringent social regulations, customs, or taboos are suspended. A portion of the responsibility for substance use may lie with the society that fails to provide treatment to addicted individuals. Factors that augment and diminish societal responsibility are listed in the box on the next page.

Factors that influence the degree of societal responsibility in addictive disorders

Factors that augment societal responsibility

Access to illicit drugs, tolerance for drug use

Risk to the property or lives of others

Court decisions for punishment rather than treatment

Individuals' refusal to obtain substance abuse treatment

Factors that diminish societal responsibility

Clear behavioral ideals or norms against substance abuse

Providers' access to early assessment and prevention strategies

Secondary interventions, such as early identification through arrests for driving while intoxicated or physical examination findings that are positive for substance abuse

Community education

Access to outpatient and community treatment

Sociocultural factors also affect the likelihood of an individual's initiating substance use. Ethnic groups in the United States differ widely in their acculturation practices with respect to alcohol and drugs. These practices begin in childhood and continue into adolescence and early adulthood, structuring attitudes about the role of individual choice and responsibility (17). Depending on the ethnic group, children may effectively have little or no choice about using one substance but have more leeway in whether to use another (18). Families and societies affect the prevalence of alcoholism by the ways in which children are acculturated in alcohol use. For example, the prevalence of alcoholism is generally low in ethnic groups in which the acculturation process includes controlled alcohol use. In some groups, it may be relatively easy to become an alcoholic (19) but not a heroin addict. In other groups, the reverse may be true (20). Thus, from the standpoint of the individual, the cultural values associated with intoxication—and with behavior that occurs during intoxication—can strongly influence the individual's sense of responsibility for his or her own intoxication and behaviors related to substance use.

Sociocultural factors are also relevant to individuals' attitudes toward substance use as well as to characteristic patterns of substance abuse among member of the same culture. The enculturation of children and adolescents to sanctioned substance use tends to occur in religious or familial settings—for example, use of alcohol during Passover by Jewish families or use of peyote during religious services by members of the Native American Church. Such cultural imperatives are associated with lower rates of abuse of the permitted substance. In contrast, enculturation to the use of unsanctioned substances occurs among peers and takes place later, typically in late adolescence or young adulthood. Occasions of use are secular, rather than religious or cultural (21). Such substances are likely to be abused if cultural norms within the peer group foster heavy use.

Cultural interpretive frames inform the experience and the expression of substance use and abuse by the members of the culture. Although the culturally sanctioned use of certain substances renders their abuse less likely, cultural and social practices may also promote substance use by fostering patterns of heavy use or by creating a norm conflict—for example, when adults drink to excess but caution children not to drink (21). Vaillant (22) has noted that alcoholics tend to have cultural backgrounds in which adult drunkenness is tolerated and in which acceptable cultural contexts for drinking without abuse—such as the consumption of wine during religious ceremonies or with meals—are not provided.

Related social questions include who is to do something about the individual's addiction and what can be done. Individuals with an addiction are potentially harmful not only to themselves but also to others. For example, an airline pilot with alcohol dependence risks the lives of passengers. Some people with addictions lack the environmental or personal resources necessary to modify their behavior. Society, on behalf of those who are placed at risk by the individual's addiction, must become involved to protect itself and to eliminate or minimize the risk. Simple incarceration is inadequate, as the addiction problem is not resolved and the addicted individual generally returns to society untreated.

Self-help perspectives

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) has been the paradigm and progenitor of contemporary self-help programs. AA has one primary purpose— "to carry its message to the alcoholic who still suffers" (23). AA has no opinions on outside matters, is not a religious or medical organization, is nonprofessional, and does not wish to engage in any controversies.

It is interesting that those who have been most afflicted by alcoholism, such as AA members, put the least blame on circumstances outside their control: "So our troubles, we think, are basically of our own making. They arise out of ourselves, and the alcoholic is an extreme example of self-will run riot, though he usually doesn't think so" (23).

AA offers no opinions about the biology of alcoholism, genetics, or sociocultural influences. AA is more interested in the alcoholic than in alcoholism. AA and other contemporary self-help programs are predicated on the assumption that although addicted persons may have tarnished aspects of themselves, recovery is always a possibility. For example, the AA program description includes the following statement: "Rarely have we seen a person fail who has thoroughly followed our path. Those who do not recover are people who cannot or will not completely give themselves to this simple program, usually men and women who are constitutionally incapable of being honest with themselves. They are not at fault, they seem to have been born that way. They are naturally incapable of grasping and developing a manner of living which demands rigorous honesty. Their chances are less than average. There are those, too, who suffer from grave emotional and mental disorders, but many of them do recover if they have the capacity to be honest" (23).

This model clearly embraces free will and personal responsibility and expects most to succeed if they are honest and rigorous in following the AA program. AA allows the exception of those who are "constitutionally incapable of being honest" and thus "are not at fault."

The AA model, which links the concept of free will to the recovery process, has been applied to other substances of abuse and has been empowering to millions of people. The individual is encouraged to admit that he or she is powerless over the abused substance and needs "a Higher Power" to restore sanity and to turn his or her will "over to the care of God as we understand him." Addicted persons are admonished to stop trying to control their use of alcohol or drugs, which has become unmanageable, and to focus on what is under their control—their responsibility and commitment to the rehabilitation process.

Religious perspectives

The use of wine is widely described in the Bible, and alcoholic beverages are not prohibited in practice or in principle. The 104th Psalm, a poem of appreciation to God for the goodness of creation, includes "wine that gladdens the heart of man, oil to make his face shine, and bread that sustains his heart" (verse 15; all verses quoted are from the New International Version). Lot's daughters made him drunk with wine to facilitate procreation and continue the family lineage (Genesis 19:32-25). In the New Testament, the apostle Paul, after admonishing the Christians at Corinth for their lack of reverence at Communion, asks, "Don't you have homes to eat and drink in?" (I Corinthians 11:22).

On the other hand, drunkenness is condemned. Isaiah, in his warning against idolatry, writes: "Priests and prophets stagger from beer and are befuddled with wine; they reel from beer, they stagger when seeing visions, they stumble when rendering decisions. All the tables are covered with vomit and there is not a spot without filth" (Isaiah 28:7-8). Similarly, Paul wrote, "Let us behave decently, as in the daytime, not in orgies and drunkenness" (Romans 13:13).

Judeo-Christian religious traditions have had a profound impact on the place of responsibility in the American legal system. In the matter of determination versus free will, this tradition holds that every human being is endowed with free will, specifically in the area of morality. An individual is assumed to have the capacity to choose righteousness or evil in a given situation. Therefore, an individual who engages in acts that are harmful to self or to others is personally responsible, whether he or she claims to be driven by inner forces, such as instinct, or by external forces.

William James (24) maintained that, unless we assume that people are free agents, concepts such as morality, remorse, and thus personal change are meaningless. James argued that attribution of responsibility and punishment of those who do not act properly make no sense if behavior is completely determined and beyond the individual's control.

Yet, within the Judeo-Christian tradition of individual accountability for personal behavior, even fervent reformers have distinguished between alcohol use and alcoholism. This point is well illustrated by William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, which treats at least 50,000 alcoholics a year in 150 facilities in the United States. Booth stated in 1890 that alcoholism "is a disease often inherited, always developed by indulgence, but as clearly a disease as ophthalmia or stone" (1).

The United Methodist Church, a mainstream Protestant denomination, supports this point or view, as expressed in its recent Book of Discipline (25): "Drug-dependent persons and their family members are individuals of infinite human worth deserving of treatment, rehabilitation, and ongoing life-changing recovery. Misuse should be viewed as a symptom of underlying disorders for which remedies should be sought."

Modern religious ethicists continue to call for personal responsibility as they address current issues in medicine and health (26). Their call goes beyond the issue of addiction—it includes diet, exercise, stress management, and appropriate use of technological advances. However, those who advocate for personal responsibility in prevention of illness also recognize that suffering and disease will occur and that the appropriate response is to implement supportive measures.

Forensic perspectives

An essential tension exists between two broad views of human behavior. The first view holds that conduct is the product of causal factors that determine choice; this can be thought of as a determinist perspective. The second view is a participant perspective and expresses an intentionalist perspective in which human behavior is considered the product of free will. In general, the medical and psychiatric points of view lean toward the deterministic, whereas the legal viewpoint is generally intentionalist. This section briefly reviews the forensic perspective on addiction.

In Robinson v. California (27), decided by the Supreme Court in 1962, the plaintiff had been stopped by the police and found to have needle marks on his arms. He admitted to occasional use of narcotics. A California statute mandated his arrest and sentence on the basis that it is a misdemeanor for an individual to be "addicted to the use of narcotics." On appeal, the Supreme Court determined that the "status" of an addiction could not justifiably be criminalized and that to do so violated the Eighth Amendment proscription of "cruel and unusual punishment."

For a brief period after Robinson v. California was decided, addiction cases were viewed liberally. For example, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down a North Carolina public drunkenness statute, stating that it punished the involuntary symptom—public intoxication—of the status of "chronic alcoholic" (28). In 1966, the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals determined that chronic alcoholism was a defense in public drunkenness, on the basis of the insanity defense, given the alcoholic's inability to conform his behavior to the requirements of the law (29).

The Supreme Court refused to apply that rationale to public drunkenness in another landmark addiction-related case, Powell v. Texas (30). The Court argued that the Robinson case prohibited states only from making "status" criminal, and that Mr. Powell was not convicted for being a chronic alcoholic but for being drunk in public. The Court concluded that, given the present state of medical knowledge, an alcoholic could not be said to be suffering from an "irresistible impulse" to drink. Presumably the required element of criminality lies in the intentional use of the drug.

Qualifications of the view that intoxication is not a defense may apply in some instances. For example, an unexpected or bizarre response to a medication may serve as an excuse. In addition, if intoxication results in a more permanent state of insanity after the immediate influence of the intoxicant has been exhausted, insanity may be a defense. Also, intoxication may be a defense if it prevented the formation of a "specific intent" that would be required in the definition of a particular offense. For example, the voluntary use of alcohol or drugs has been held to be relevant in determining whether a defendant was able to perform the mental operations necessary to commit first-degree rather than second-degree murder—that is, premeditated rather than unpremeditated but deliberate murder.

Diminished capacity is an affirmative defense that does not result in complete exculpation of a criminal charge but may lessen the charge or the degree of punishment. The first judicial statement of diminished capacity occurred in Scotland in 1867. The defendant's alcoholism was held to be a mitigating circumstance justifying a reduction of a charge of murder to culpable homicide (31). The question of amnesia, such as an alcoholic blackout, has also been raised. Amnesia typically is not a defense, as it is assumed that the individual had the capacity to form intent and therefore to commit a crime, even if the person cannot remember it.

Although addiction may not provide a defense to a legal charge, it may result in the defendant's being found incompetent to stand trial. For example, an individual who continues to use drugs or alcohol may be indifferent to his or her problems and may need treatment before being brought to trial. Similarly, a state of withdrawal and strong cravings may compromise the ability to assist in one's defense.

The courts have at times regarded addiction as a disease and assumed that intoxication is an outgrowth of that disease process; therefore, the requisite mens rea (guilty mind) could not be formed. Mens rea as well as actus reus (guilty act) are necessary for criminal intent. The Durham Insanity Test (32), which demands only that the criminal behavior be the product of mental illness or defect, has resulted in some successful defenses for addicts. However, the prevailing view in most jurisdictions is that moral concerns about allowing intoxication to mitigate responsibility and the need to protect the public override the claim that intoxication disproves mens rea. Therefore, addiction and related behaviors are rarely defensible in our legal system.

Conclusions

The degree to which we as psychiatrists view patients as responsible for their addictions is central to our approach to them. If we believe that patients with substance use disorders possess the capacity to discontinue their addiction without direct assistance, we will be tempted to minimize our role in this effort. In many instances, however, an individual is not solely responsible for an inability to end a substance use disorder. A man who was abused as a child is a product of those early experiences and may not possess the coping abilities necessary to self-soothe and adapt to normal life stressors. A woman desiring treatment for cocaine addiction may not have the financial resources to attend an outpatient program or the family support to have her children cared for while she attends an inpatient program.

If we are to develop effective treatment strategies for substance use disorders, we must understand that addicted patients cover an entire spectrum, ranging from those whose abstinence is considerably related to personal responsibility to those whose abstinence will require intensive psychiatric and rehabilitative treatment. If we recognize that an individual with an addiction may not be fully able to exercise free will, then society's obligation to intervene becomes stronger. A common societal intervention today is to criminalize addiction, or at least the behaviors associated with addiction. For many addicts, the only way they will receive treatment "in spite of themselves" is to end up in the criminal justice system, which is gradually evolving into an involuntary treatment system.

There is a continuum of responsibility for the individual addict, and society could respond with appropriate treatments along that continuum. However, the ethical dilemma remains: should treatment be mandated for addicted individuals who do not want treatment? Is mandated treatment an effective allocation of resources in an already inadequately funded system? Society can force treatment for addiction through legal mechanisms, such as drug courts, but does that compromise the individual's right to free choice? Why are treatment resources in such short supply? Should the billions of dollars the U.S. government spends each year on the "war on drugs" be allocated to treatment approaches rather than fighting the suppliers?

The legal culpability, which the individual bears, does not relieve society from its responsibility to develop and provide competent treatment and rehabilitation. If we are to develop effective treatment strategies for addictions, we must frame an understanding of responsibility that acknowledges that many patients with substance use disorders have vulnerabilities in the form of psychiatric problems or poorly regulated emotional states. Nevertheless, we expect patients to take responsibility for seeking out and participating in their treatment for addiction and any other psychiatric disorders. Sentences imposed on addicts by the courts could include judgments that take into account both the individual and societal factors discussed here. Alternative sentencing strategies could be initiated on a case-by-case basis and in consideration of special needs.

The issue of personal responsibility in addiction cuts across neuroscience, clinical practice, religion, culture, and legal codes. Our societal and professional perspectives on personal responsibility meet at an ever-changing intersection as science, theories, and traditions evolve with time. Hopefully these changes will be progressive, serving the separate and sometimes conflicting needs of individuals and society.

The members of the Committee on Addictions of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry are Beth K. Boyarsky, M.D., Stephen Dilts, M.D., Ph.D., Richard J. Frances, M.D., William A. Frosch, M.D., Marc Galanter, M.D., Frances Levin, M.D., Collins Lewis, M.D., Earl Loomis, M.D., John A. Menninger, M.D., Edgar P. Nace, M.D., Richard Suchinsky, M.D., Maria Sullivan, M.D., John Tamerin, M.D., Joseph Westermeyer, M.D., Ph.D., David Wolkoff, M.D., and Douglas Ziedonis, M.D. Send correspondence to Dr. Nace, 7777 Forest Lane, Suite B413, Dallas, Texas 75230 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Ratings of the degree of responsibility of individuals in ten hypothetical situations involving substance usea

a The questionnaire, written by Edgar PNace, M.D., was completed by 13 of 15 available committee members.

1. White WL: Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America. Bloomington, Ill, Chestnut Health Systems/Lighthouse Institute, 1998Google Scholar

2. Koob GF: Neural mechanisms of drug reinforcement. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 654:171-191, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Schuckit MA: Low level of response to alcohol as a predictor of future alcoholism. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:184-189, 1994Link, Google Scholar

4. Porjesz B, Begleiter H: Neurophysiological factors in individuals at risk for alcoholism. Recent Developments in Alcoholism 9:53-67, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

5. Menninger JA, Baron AE, Tabakoff B: Effects of abstinence and family history for alcoholism on platelet adenylyl cyclase activity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 22:1955-1961, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Buck KJ, Harris RA: Neuroadaptive responses to chronic ethanol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 15:460-470, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Nestler EJ, Guitart X, Ortiz J, et al: Second messenger and protein phosphorylation mechanisms underlying possible genetic vulnerability to alcoholism. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 708:108-118, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Leshner AI: Drug addiction research: moving toward the 21st century. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 51:5-7, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. McHugh PR, Slavey PR: The Perspectives of Psychiatry, 2nd ed. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998Google Scholar

10. Galanter M: Psychotherapy for alcohol and drug abuse: an approach based on learning theory. Journal of Psychiatric Treatment and Evaluation 5:551-556, 1983Google Scholar

11. Glover E: On the etiology of drug addiction, in On the Early Development of the Mind. Edited by Glover E. New York, International University Press, 1932Google Scholar

12. Khantzian EJ, Mack JE, Schatzberg AF: Heroin use as an attempt to cope: clinical observations. American Journal of Psychiatry 131:160-164, 1974Link, Google Scholar

13. Wurmser L: Psychoanalytic considerations of the etiology of compulsive drug use. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 22:820-843, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Khantzian EJ: The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry 142:1259-1264, 1985Link, Google Scholar

15. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC: In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist 47:1102-1114, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Maddux JF, Desmond DP: Crime and treatment of heroin users. International Journal of the Addictions 14:891-904, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Spiro M: The acculturation of American ethnic groups. American Anthropologist 57:1240-1252, 1955Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Catalano RF, Morrison DM, Wells EA, et al: Ethnic differences in family factors related to early drug initiation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 53:208-217, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Bennett LA, Ames GM: The American Experience With Alcohol: Contrasting Cultural Perspectives. New York, Plenum, 1985Google Scholar

20. Basher T: The use of drugs in the Islamic world. British Journal of Addiction 76:233-243, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Westermyer J: Cultural aspects of substance abuse and alcoholism. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 18:589-605, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Vaillant GE: The Natural History of Alcoholism: Causes, Patterns, and Paths to Recovery. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1983Google Scholar

23. Alcoholic Anonymous. New York, Alcoholic Anonymous World Services, 1976Google Scholar

24. James W: The Principles of Psychology. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1952Google Scholar

25. The Book of Discipline of the United Methodist Church, 2000. Nashville, United Methodist Publishing House, 2000Google Scholar

26. Rogers J: Medical Ethics, Human Choices: A Christian Perspective. Scottdale, Pa, Herald Press, 1988Google Scholar

27. Robinson v California, 370 US 660, 82 S Ct 1417 (1962)Google Scholar

28. Driver v Hinnant, 356F 2d761 (CA 4 NC) (1966)Google Scholar

29. Easter v District of Columbia, 361F 2d, (CA DC) (1966)Google Scholar

30. Powell v Texas, 392 US 514 88 S Ct 2145 (1968)Google Scholar

31. Weinstock R, Leong GB, Silva JA: California's diminished capacity defense: evolution and transformation. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 24:347-366, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

32. Durham v US, 94 US App DC 228, 214 F 2d 862 (1954)Google Scholar