The Impact of Closing a State Psychiatric Hospital on the County Mental Health System and Its Clients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This three-year study examined the impact of closing a state psychiatric hospital in 1991 on service utilization patterns and related costs for clients with and without serious mental illness. METHODS: The cohort consisted of all individuals discharged from state hospitals and those diverted from inpatient to community services and enrolled in the unified systems project, a state-county initiative to build up the service capacity of the community system. The size of the cohort grew from 1,533 enrollees to 2,240 over the three years. Information on the types, amounts, and cost of all services received by each enrollee was compiled from multiple administrative databases, beginning two years before enrollment and for up to three years after. The data were analyzed to reveal patterns of and changes in service utilization and related costs. RESULTS: Replacement of most inpatient services with residential and ambulatory services resulted in significant cost reduction. For project enrollees, a 94 percent reduction in state hospital services resulted in cost savings of more than $45 million during the three-year evaluation period. These savings more than offset the funds used to expand community services. Overall, the net savings to the system for mental health services for this group was $3.4 million over three years. CONCLUSIONS: The hospital closure and infusion of funds into community services produced desired growth of those services. The project reduced reliance on state psychiatric hospitalization and demonstrated that persons with serious mental illness can be effectively treated and maintained in the community.

Like many regions across the country, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, has deinstitutionalized the care of its mentally ill population. In 1991 one state hospital closed and two other facilities were downsized, in tandem with the enhancement of the local community system.

In this paper we describe the impact of this initiative on clients of the county mental health system, particularly persons with serious mental disorders, as well as on the system itself. Our evaluation focused on several management issues, including the shift away from reliance on state hospital services, the restructuring of an urban service system for persons with serious mental disorders, economic and service system outcomes, and policy implications, such as whether persons with serious mental disorders can be as effectively treated in noninstitutional settings.

Over the last three decades, deinstitutionalization—the closing or downsizing of state psychiatric hospitals—was based on two major premises. The first was that a shift of the locus of care from institutions to the community would benefit persons with mental illness, improve their clinical status, and enhance their quality of life; the second was that such a shift would be cost-effective and would conserve public funds and resources. Over that period, deinstitutionalization proceeded at an uneven rate for many reasons, which included multiple and at times conflicting clinical and political factors, mixed financial incentives, and a paucity of evidence about service cost efficiencies and consumer outcomes. Nevertheless, in 1994 a report by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors revealed that 42 of 54 states and territories were downsizing their state hospital systems, and 12 were closing facilities (1). However, according to Rothbardand colleagues (2), most states have downsized rather than closed facilities.

In the earliest phase of deinstitutionalization, federally funded community mental health centers served mostly less disabled clients, and relatively few community mental health resources were available for the care of discharged persons with serious mental illness. A later phase of deinstitutionalization was based on the premise that dollars should follow the clients from state facilities into the community (3). Only in the most recent phase has a model been employed in which the dollars preceded the clients. This model was used when Pennsylvania closed the Philadelphia State Hospital (2) and also in the Allegheny initiative, as reported elsewhere (4) and in this paper.

Shifting the locus of care from regional state hospitals to local communities raised many important questions, which the comprehensive project evaluation described here attempted to answer. What was the impact of this change on the configuration of community mental health programs? Did an increase in the number of persons with serious mental disorders being served in the community affect services to clients without serious disorders? How did patterns of service utilization by persons with serious mental disorders change, and, particularly, what was the effect on consumption of public service resources? Were community services cost-effective? And, finally, how did the change in the locus of care affect client outcomes, and how were these outcomes related to the types and amounts of services received? In this paper we focus on the questions concerning service utilization and costs.

Studies that address the impact of downsizing or closing of state hospitals span three decades (2,3,5,6,7,8). These studies have addressed a broad range of research and evaluation issues. Early on, authors discussed the political implications of unbundling the multiple functions performed by state hospitals (6,9,10,11) and the need for a paradigm shift preparatory to designing community mental health care systems to replace those functions (12). However, others argued that as long as community programs remained unprepared to handle and care for persons with serious mental disorders, complete systems of care needed to include state hospitals. The call to preserve state hospitals sought to ensure that professional and clinical expertise and experience were not superseded by financial and political considerations (13,14,15) and that a clinical safety net was provided for service recipients (16,17,18).

Several researchers have examined one of the major premises of deinstitutionalization, that is, the expected replacement of costly and restrictive services with more appropriate, cost-effective services. Bedell and Ward (19) found that intensive community residential programs provided a cost-efficient alternative to hospitalization. Others have suggested that lower community costs might be due to significant cost shifting, for example, from state and local authorities to Medicaid (3,20).

Rothbard and associates (2) and Schinnar and colleagues (21) reported on comprehensive service utilization patterns, resource consumption, and costs expended by the community service system after the closing of the only state hospital in Philadelphia. The authors found a complex set of changes in service utilization and costs. The use of residential and case management services increased as the use of extended inpatient services decreased. However, the cost of an episode of care and the mean annual per-patient cost of care increased after closure of the state hospital, probably due to an increase in acute care hospitalizations in general community hospitals.

Most published studies have relied on cross-sectional data and have employed a range of methods to capture system and client outcomes, including use of administrative data (2,21) and interviews and client assessments (22,23,24,25). The comprehensive evaluation project reported on in this paper used an extensive array of both administrative and client assessment data, which was integrated into ongoing clinical and management processes, allowing for a unique cross-sectional as well as longitudinal perspective on system and client change.

Methods

The unified systems project

A 430-bed state hospital in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, was gradually closed starting in January 1991 and ending in June 1992. Stringent limits were placed on admissions to two other facilities, which together served ten catchment areas with a total population of 1.3 million residents. The closure was the keystone of a state-county initiative, the unified systems project. The goal of the project was to reduce reliance on state hospital services, build up the service capacity of the community system, and meet the service needs of clients either discharged from the state hospital or diverted from hospital admission to alternative community services.

To build up local capacity, the state provided the local mental health service system with almost $34 million over three years. Each catchment area had a program that was assigned specific clients and received initial funding from the project, as well as additional funds contingent on meeting scheduled targets of reduced utilization of state hospitals. As a result, most project funds preceded the discharged clients into the community system and were thus available to build up local service capacity. About half of the new funds were used for development of residential programs, and about a third were used for employing more case managers.

Every person discharged from the hospital that was gradually being closed and all persons who met hospital admission criteria but who were diverted from inpatient services to community-based programs were automatically enrolled in the unified systems project. A computerized project database included the records of all enrollees. The record consisted of typical identifiers and enrollment data and was created either at hospital discharge or when a patient was diverted from inpatient services. Enrollment began January 1, 1991, and continued for the duration of the project.

A research group based at the University of Pennsylvania that was not involved in the project was contracted to design and conduct the three-year (1991-1993) evaluation. Multiple stakeholders participated in its design and implementation; they included consumers and their families, the state mental health agency and its regional service management, and county and service agencies.

Design of the evaluation

The design of the evaluation of the unified systems project has been reported in detail elsewhere (4). The evaluation used both system and client data, including existing administrative data and specially collected data. Data on service utilization were reconstructed for each enrollee for the two years preceding his or her enrollment in the unified systems project; data were also compiled for at least three years after enrollment. Client status and outcome data about level of functioning, symptoms, substance use, and quality of life were specially collected every three months during the project. The comprehensive evaluation had three major objectives: assessment of system-level changes, including patterns of service utilization and costs; assessment of client-specific outcomes; and examination of client outcomes in relation to services received. This paper addresses the first objective.

Characteristics of the cohort group

Members of the study cohort were clearly defined and identified through records in the enrollment database. The initial cohort numbered 1,533 and grew to 2,240 with enrollment of clients newly discharged or diverted from inpatient care.

The mean±SD age of cohort members was 44±10. The group was almost equally divided between males and females (52 percent females). About two-thirds (61 percent) of project enrollees had never been married, and only 10 percent were married at the time of enrollment. As is typical in treated client populations, minorities constituted a larger proportion of the cohort than of the general population (29 percent versus 13 percent), possibly due to lower socioeconomic status and a greater resulting need for public services. One-third of the cohort had completed high school, and a fifth (21 percent) had had some college or higher education.

The diagnoses of enrollees indicated a significantly disabled group; half had a diagnosis of some form of schizophrenia, 15 percent had a major affective disorder, and 20 percent had an anxiety disorder.

Data

Enrollees' service utilization and cost data were derived from existing administrative and billing databases. Client-specific service data were extracted from four databases. The patient-client information system contains client-specific records of all admissions and discharges to and from all state hospitals. The client information system contains client-specific records of admissions to, discharges from, and services received in all county-funded community mental health programs. The Medicaid management information system and its companion eligibility database, the Medicaid client information system, contain client-specific data on paid claims for all mental health services provided to Medicaid recipients in the community, including services in general hospitals. The intensive case management program database contained information on units of case management received and discharge data for persons in the case management program.

Procedure and analysis

Administrative data about clients, client characteristics, and all services received were integrated from the four different databases. Because complete service data were compiled for each member of the cohort from two years before enrollment until the end of the project, county and Medicaid service data had to be searched repeatedly to retrieve the records of new enrollees. The search resulted in large consumer-specific records that included basic sociodemographic and diagnostic data, as well as a longitudinal file of all services received. Depending on the question addressed, the evaluation used a combination of methods to report findings, including simple descriptive statistics, graphic representations, and, for relationships between services received and outcomes, analyses of variance and linear regression methods.

Results

A major goal of the evaluation of the unified systems project was to examine important system-level changes, including linkage of clients to community programs, patterns of service use, and related costs.

Continuity of care

Ten percent of enrollees received their first case management service the day they were discharged or diverted from the state hospital, 20 percent by day 5 after discharge or diversion, and 40 percent within three months. Twenty-one percent of enrollees received their first community mental health service, other than intensive case management, the same day they were discharged from the hospital. By day 6 after discharge or diversion, half the clients received a face-to-face service, by day 15 two-thirds were engaged, and after six months 80 percent were engaged in community services. By the end of the first year after discharge or diversion, every client was linked to at least one community service.

Service utilization

With the infusion of $34 million into its budget, the community mental health service system experienced major growth and expansion. The number of enrollees in the unified systems project who received partial care services more than quadrupled between the eighth quarter of data collection, or the start of the project (January to March 1991), and the 18th quarter (July to September 1993); the number rose from 218 to 905. The number of clients in the mental health system not enrolled in the project (persons not discharged or diverted from state hospitals) who received these services also increased over the same period. However, they increased at a slower rate, from 3,181 to 3,764.

Among project enrollees, recipients of intensive case management increased from 70 to 835. Among clients not enrolled in the project, the number increased from 357 to 967.

For the same period, the number of units of service provided also increased substantially. The number of residential days increased from 3,277 in the eighth quarter, when the project started, to 12,446 by the 18th quarter, while the number of units of partial care services (half-days of care) rose from 8,618 to 29,514. For the same time period, units of intensive case management increased from 1,226 to 14,706, and units of other services, including outpatient sessions and medication checks, climbed from 20,713 to 54,765.

Heavy users

The term "heavy users" refers to a relatively small proportion of clients who consume a disproportionately large share of services (26,27,28,29). Numerous researchers have documented the existence of this group. For example, Hadley and associates (26) reported that 35 percent of users of public mental health services in Philadelphia accounted for approximately 75 percent of the annual dollars spent. Kamis-Gould and colleagues (30) found that 10 percent of children and adolescent recipients of mental health services in Philadelphia consumed 66 percent of the resources.

This phenomenon has received a great deal of attention, based on the assumption that identifying heavy users and providing them with more targeted, intensive, community-based services might forestall crises and decrease the use of emergency room services and hospitalization, ultimately reducing service consumption by heavy users to more proportionate levels. Typically, studies have examined annual and other cross-sectional service utilization data. The unified systems project evaluation afforded a rare glimpse into client-specific patterns of service use over many years.

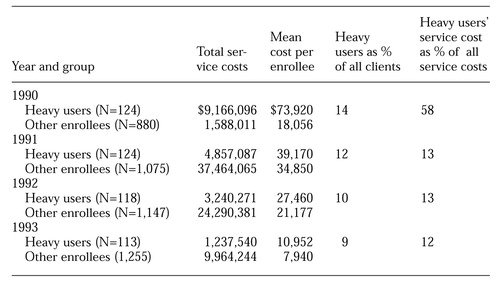

The cohort of project enrollees had its own share of empirically identified heavy users. For each of four years, 1990, 1991, 1992, and 1993, between 14 percent and 15 percent of enrollees consumed between 37 percent and 66 percent of service resources, in terms of aggregate costs. Table 1 provides a longitudinal view of the 1990 heavy-users group. In the three years after these 124 clients were identified as heavy users, their consumption of resources dropped substantially, to more proportionate levels among all enrollees.

In year 1, this group of heavy users constituted 14 percent of enrollees but accounted for 58 percent of costs. However, by year 2, costs for the same group, which then represented 12 percent of the population, amounted to only 13 percent of costs, and by year 3, as 10 percent of the population, this group accounted for only 13 percent of total costs. For the fourth year (a half-year of reported data), this group represented only 9 percent of the population, and the resources consumed totaled only 12 percent of costs.

Service substitution and costs

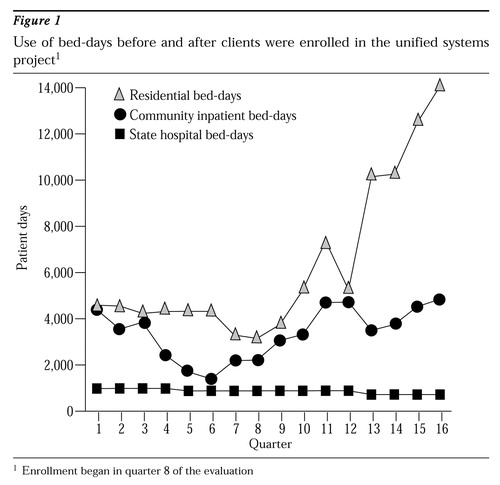

A major objective of the hospital closing and creation of the unified systems project was the intentional replacement of restrictive and expensive services with services that were both more appropriate and less expensive—specifically, substituting community services for institutional services, and ambulatory and residential services for inpatient services. Figure 1 traces pre- and postdischarge bed-day use in state hospitals, community inpatient facilities (general hospitals), and residential facilities over 16 quarters.

As can be seen, use of state hospital bed-days fell slightly through the 12th quarter, four months after the start of the project, at which time use dipped again for the remainder of the evaluation period. Use of bed-days in community inpatient facilities fell sharply before the eighth quarter, when the project began, then more than tripled from that point on. The most dramatic change involved a more than threefold increase in residential program days. Overall, Figure 1 reflects a replacement of state hospital days with some community inpatient services but mostly with residential services.

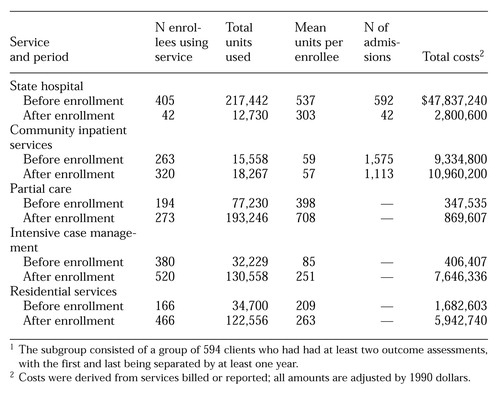

Table 2 presents data that show a striking change in service use and related costs for a subset of the study cohort. The subset consisted of 594 clients who had had at least two outcome assessments, with the first and last being separated by at least one year.

During the years before enrollment, 405 of 520 clients in this subgroup used 217,442 state hospital days, 263 clients used 15,558 community inpatient days, 194 clients used 77,230 units of partial care, 380 used 32,229 units of intensive case management, and 166 used 34,700 residential days. Corresponding postdischarge data shown in Table 2 indicate that, in general, after enrollment in the project more clients were using far more services, with one exception—state hospital days. The number of clients using state hospital days fell by almost 90 percent, and the number of state hospital bed-days used fell by 94 percent.

As Table 2 shows, postdischarge increases in the cost of community services ranged from 17 percent for community inpatient services to 75 percent for intensive case management. Despite dire predictions that the discharged clients would have long hospital stays in the community, and contrary to the experiences reported by Rothbard and associates (2), more clients used community hospitals, but they had fewer admissions and shorter lengths of stay than before enrolling in the program.

For this enrollee subgroup, a 94 percent reduction in expensive state hospital services resulted in cost savings of $45,036,640 during the four years covered by this analysis. These savings more than offset both the additional funds that had been infused into the community system, $34 million, and the funds used to expand community services, $13,647,538. Overall, the net savings to the system for mental health services for this group amounted to $3,389,102 during the evaluation period.

Discussion and conclusions

The evaluation of the unified systems project was designed as a comprehensive process, to be integrated into ongoing clinical and management activities. Results show that closing the state hospital and enhancing the community system had a major impact on the overall service system. Most enrollees experienced a fairly smooth transition into the community through intensive case management and other routes. One year after discharge, no clients had been lost to follow-up, a remarkable achievement.

The shift away from institutional to community services, coupled with additional funding, resulted in significant growth in the community service system and far greater use of community services. The increased use suggested that clients' needs were being addressed through this new project. Intensive case management, which had initially been a minor program element, quickly assumed a central position in the new system as the number of enrollees served quadrupled over the evaluation period and the use of units of case management increased by a factor of 19.

Another dramatic change involved a more than threefold increase in the use of residential program days, suggesting responsiveness to the critical need for such programs to maintain many adults with serious mental disorders in the community. Consumption of other community program services, including partial care, also multiplied, while reliance on inpatient care, especially at state hospitals, was drastically reduced.

The major, and obvious, beneficiaries of the unified systems project were the enrollees. One initial concern, which the evaluation addressed, was that the introduction of clients with chronic and severe mental disorders into the community system might negatively affect other client populations not enrolled in the project. However, notable increases in the use of each type of community service by clients not enrolled in the project suggests that they also benefited. For example, the number of these clients who received intensive case management also grew, although at a slower rate, with a growth factor approaching 4.

Results of this evaluation also validated and extended our understanding of heavy users of services. Cross-sectional data buttressed findings of other studies, suggesting that in any given year, 14 or 15 percent of high users may account for as much as two-thirds of the total service expenditures. However, longitudinal data from the evaluation afford a new perspective on the heavy-users issue. When the 124 clients who were identified as heavy users in 1990 were followed for three years, we discovered that this group's use of services quickly dropped to levels proportionate to their representation in the study cohort. Because the drop in use may be partly attributable to the episodic nature of their disorders, the concept of "heavy users" might bear re-examination.

One focus of the management-oriented component of the evaluation concerned cost. As anticipated, the intended substitution of services and related changes produced savings that exceeded the costs of meeting the greater demand for community services. Because these results conflict with those of our colleagues (2), additional research and replications are desirable.

We can conclude that, first, the closing of the state hospital, combined with the concurrent infusion of funds into the community system, produced the desired growth in community services and a clear reduction in reliance on institutional care. Besides conserving public resources, the intentional substitution of services resulted in more appropriate care that was more likely to aid in clients' recovery and growth. Second, and also as intended, the greatest growth occurred in intensive case management services. Availability of these services may provide the key to successful transitions of institutionalized clients into the community. They may also prevent institutionalization of those who would not be able to live in the community without such services. Not as measurable as the monetary savings will be the benefits related to creating a less disruptive treatment process for these clients and their families.

The evaluation of the unified systems project lends support to the policy of deinstitutionalization. It demonstrates that clients with severe and chronic mental disorders can be treated effectively in the community, at least when system resources are adequate to the task. Changes need not result in additional costs to the system; at least in this case, such changes led to overall net savings of almost $3.5 million. Finally, the results of the evaluation suggest that a large-scale change can be implemented with no apparent detriment—and more likely some benefit—to other client groups such as children and elderly persons, and with an even larger, if harder to measure, benefit to clients, their families, and the community of which they are now more truly a part.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Arlene Stanton, Ph.D., for her assistance.

Dr. Kamis-Gould is research assistant professor, Mr. Snyder is project manager, and Dr. Hadley is professor at the Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research in the department of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, 3600 Market Street, Room 709, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Casey is director of evaluation in the Allegheny County Office of Mental Health and Mental Retardation.

Figure 1. Use of bed-days before and after clients were enrolled in the unfied systems project1

1 Enrollment began in quarter 8 of the evaluation

|

Table 1. Reductions in services costs over time for 124 clients identified in 1990 as heavy users and costs for other enrollees in the unified systems project

|

Table 2. Service use and costs by a subgoup of 594 enrollees in the unified systems project during the two years before and after project enrollment1

1. Lutterman T: The state mental health agency profile system, in Mental Health, United States. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1995Google Scholar

2. Rothbard AB, Schinnar AP, Hadley TR, et al: Are Community-Based Services Cost-Efficient Alternatives to State Psychiatric Hospitals? Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Center for Mental Health Policy and Services, 1996Google Scholar

3. Okin RL: Testing the limits of deinstitutionalization. Psychiatric Services 46:569-574, 1995Link, Google Scholar

4. Kamis-Gould E, Hadley TR, Rothbard AB, et al: A framework for evaluating the impact of state hospital closing. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 22:497-509, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Greenblatt M, Glazier E: The phasing out of mental hospitals in the US. American Journal of Psychiatry 132:1135-1140, 1975Link, Google Scholar

6. Ashbaugh JW, Bradley VJ: Linking deinstitutionalization of patients with hospital phase-down: the difference between success and failure. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 30:105-110, 1979Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Geller JL, Fisher WH, Simon LJ, et al: Second-generation deinstitutionalization: II. the impact of Brewster v Dukakis on correlates of community hospital utilization. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:988-993, 1990Link, Google Scholar

8. Gordon B: Outcome After Discharge From Philadelphia State Hospital: A Profile of Recidivist and Non-Recidivist Populations Relative to Community Tenure, Community Living Arrangements, and Residential Stability. Philadelphia, Office of Mental Health, 1991Google Scholar

9. Goldman HH, Taube CA, Regier DA, et al: The multiple functions of the state mental hospital. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:296-300, 1983Link, Google Scholar

10. Semke J, Fisher WH, Goldman HH, et al: The evolving role of the state hospital in the care and treatment of older adults: state trends, 1984 to 1993. Psychiatric Services 47:1082-1087, 1996Link, Google Scholar

11. Okin RL: The future of state hospitals: should there be one? American Journal of Psychiatry 140:577-257, 1983Google Scholar

12. Pepper B, Ryglewicz H: The role of the state hospital: a new mandate for a new era. Psychiatric Quarterly 37:230-257, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Gralnick A: Deinstitutionalization: origins and signs of failure. American Journal of Social Psychiatry 3:8-12, 1983Google Scholar

14. Gralnick A: Build a better state hospital: deinstitutionalization has failed. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:738-741, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar

15. Bachrach LL: The future of the state mental hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:467-474, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Bachrach LL: Deinstitutionalization: a semantic analysis. Journal of Social Issues 45:161-171, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Taube CA, Goldman HH: State strategies to restructure psychiatric hospitals: a selective review. Inquiry 26:146-156, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lamb HR: Is it time for a moratorium on deinstitutionalization? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:669, 1992Google Scholar

19. Bedell J, Ward JC: An intensive community-based treatment alternative to state hospitalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:533-535, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

20. Bachrach LL: The state of the state mental hospital in 1996. Psychiatric Services 47:1071-1078, 1996Link, Google Scholar

21. Schinnar AP, Rothbard AB, Hadley TR: Effects of State Mental Hospital Closing: Final Report to the Pew Charitable Trust. Grant 92-01985-000. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, 1996Google Scholar

22. Bond GR, Witheridge TF, Dincin J, et al: Assertive community treatment for frequent users of psychiatric hospitals in a large city: a controlled study. American Journal of Community Psychology 18:865-891, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Sullivan G, Wells KB, Leake B: Clinical factors associated with better quality of life in a seriously mentally ill population. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:794-798, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

24. Huxley P, Werner R: Case management, quality of life, and satisfaction with services of long-term psychiatric patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:799-802, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Dickerson FB: Assessing clinical outcomes: the community functioning of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:897-902, 1997Link, Google Scholar

26. Hadley TR, McGurrin MC, Pulice RT, et al: Using fiscal data to identify heavy service users. Psychiatric Quarterly 61:41-48, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Holohean EJ, Pulice RT, Donahue SA: Utilization of acute inpatient psychiatric services: "heavy users" in New York State. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 18:131-181, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Hadley TR, Culhane DP, McGurrin MC: Identifying and tracking heavy users of acute psychiatric inpatient services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 19:279-290, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Kent S, Fogarty M, Yellowlees P: A review of studies of heavy users of psychiatric services. Psychiatric Services 46:1254-1257, 1995Link, Google Scholar

30. Kamis-Gould E, Markel-Fox S, Rothbard AB, et al: Children with mental disorders in multiple delivery systems. Paper presented at the conference "A system of care for children's mental health," Tampa, Fla, Mar 6-8, 1995Google Scholar