Focus on Women: Mothers With Mental Illness: I. The Competing Demands of Parenting and Living With Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study is to understand the parenting experiences of women with mental illness from the perspectives of mothers and case managers employed by the state department of mental health. METHODS: Six focus groups of mothers and five focus groups of case managers met to discuss the problems facing mothers with mental illness and to recommend solutions. Focus-group transcripts were coded and items grouped by themes in qualitative analyses to explore the conflicts mothers face in meeting the dual challenges of parenting and living with mental illness. RESULTS: Mothers and case managers identified sources of conflict in four thematic categories: the stigma of mental illness, day-to-day parenting, managing mental illness, and custody of and contact with children. CONCLUSIONS: Many of the issues of mothers with mental illness are generic to all parents; others are specific to the situation of living with mental illness. Mothers with mental illness must play a role in developing standards for clinical care and the research agenda in this area.

Parenthood is a normative life experience for many individuals—one that defines the roles and meaning of adulthood (1,2). For women living with mental illness, motherhood may be a normalizing life experience_creating roles and meaning for women who would rather define themselves as parents than as patients or even as paid workers (3,4,5,6,7). Motherhood offers the opportunity to develop competencies in a major life role (8); failure as a parent contributes to never-ending shame and humiliation (9).

Although outcomes for children of mothers with mental illness have been studied extensively (10,11,12), the experiences of mothers and the impact of parenting on maternal well-being have only recently received attention (5,13,1415,166). Previous studies of parenting and related experiences for women with severe mental illness have been limited by small convenience samples, typically of women in hospital settings (17). Mothers' perspectives about their parenting experiences have been ignored. Women with mental illness appear to want the opportunity to voice their grief, fears, and fantasies about motherhood (3).

Women with severe mental illness may be as likely as women in the general population to have children (6,13,17). However, the rate of custody loss for mothers with mental illness is high (6,17). Nonetheless, in a recent study of issues for women with severe mental illness, more than 80 percent of mothers reported raising or helping to raise at least one of their children (7). A similar percentage was currently in contact with at least one child. More than one-quarter of the mothers had at least one child living with them. Almost 30 percent of the mothers indicated their illness made it more difficult to be a good parent.

A few researchers have begun to describe the day-to-day issues of mothers with mental illness. Sands (5) compared the experiences of ten single, low-income mothers in a community rehabilitation residential program for mothers with severe mental illness and their children with the experiences of eight single, low-income mothers without psychiatric impairment. She found that mothers with mental illness had a strong desire to develop "normal" lives for themselves and their children but had greater difficulty disciplining their children and felt the effects of role strain and stress.

The mothers in Sands' study tended to minimize their illness and the impact their illness had on their children; they did not directly acknowledge the need for guidance or help with parenting. The fear of custody loss contributed to the mothers' reluctance to discuss the need for help with parenting skills. Sands concluded that the needs of mothers and of their children must both be considered in decisions to maintain or disrupt relationships.

In an interview study of mothers with mental illness living in the community, 24 women responded to questions about their parenting behaviors and attitudes, the problems and joys of having children, and interpersonal supports (18). One-fourth felt that disciplining their children was the hardest thing about being a mother. Almost half reported feeling bad as mothers about illness-related issues: using drugs (substance abuse), managing feelings, and their mental illness in general. The majority of mothers described parenthood as promoting their growth and development, even though it was stressful.

The study reported here distinguishes itself from previous research on motherhood and mental illness in several ways. Mothers with mental illness were given the opportunity to share their perspectives as parents in focus groups. Group interaction can produce data and insights that might not emerge from individual interviews (19). Peer support can minimize the power differential between participants and researchers and can encourage mothers to talk about the full range of their experiences.

Data from the focus groups were analyzed qualitatively. Qualitative methods were appropriate given the paucity of research in this area. These methods are well suited to research that is exploratory and are consistent with an emphasis on participants' perspectives (20). Rather than force data into preconceived categories derived from existing theories, our goals were to thoroughly describe mothers' experiences and to identify variables and relationships that would lead to the development of theory and would inform future research and clinical practice (21).

The purpose of the study was to understand the parenting experiences of women with severe mental illness from the perspectives of both mothers themselves and case managers. Six focus groups of mothers and five focus groups of case managers were conducted across Massachusetts in the spring and summer of 1994. Participants were asked to respond to two questions: what are the problems facing mothers with mental illness, and what are some solutions or recommendations you would make? Transcripts of the focus-group interviews were coded and analyzed to provide information about the conflicts mothers face in meeting the dual challenges of parenting and living with mental illness.

Methods

Recruitment of mothers with mental illness

An average of 15 mothers were randomly recruited from the population of mothers living in the community who were currently receiving case management services in each of six area offices of the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. Clients who receive case management services from the department of mental health are persons who because of serious, long-term mental illness are not able to meet basic needs of shelter, food, clothing, and self-care; persons who have had two or more psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 12 months; and homeless persons with mental illness. The mothers who participated in the focus groups met the following additional criteria: they were between age 19 and 59; they were living with, communicating regularly with, or involved in custody proceedings with at least one biological child under the age of 13; and they were English speaking.

These criteria reflected our focus on women living in the community who could talk about their current experiences with parenting a pre-teen. One hospitalized mother participated as she was being discharged the next day from the state hospital and was to be reunited with her family. Mothers were drawn from different geographic regions to reflect any natural variation in needs or services available across Massachusetts. In addition, random recruitment helped ensure that the mothers who were willing to participate in the focus groups were representative of the larger population of mothers and mitigated against any bias introduced by the focus-group method.

One hundred mothers were selected to attend focus groups. Of these, 65 agreed to participate. Eleven mothers did not participate because their case managers were reluctant to invite them, indicating that participation would be too upsetting for these clients. Eleven mothers did not meet study criteria. Seven mothers declined participation. Six mothers were not available at the times the focus groups were scheduled.

Of the 65 mothers who agreed in advance to attend, 42 actually participated in one of the six mothers' focus groups. Lack of transportation on the day of the focus group session was the most frequently cited reason for nonattendance. Mothers signed informed consent forms when they arrived at the group sites. They received a stipend of $50 for participating.

Before participating in the focus groups, the mothers completed a questionnaire that requested information on their background and demographic characteristics, their clinical characteristics, the number of children they had and where the children lived, and the types of supports they received. Questions about housing were taken from materials used in California's consumer-based Well-Being Project with permission (22).

Recruitment of case managers

Focus groups of case managers were conducted to provide additional insight into and corroboration of the contextual issues contributing to mothers' experiences, service utilization, and outcomes for themselves and their families. Case managers who worked for the department of mental health were selected for this study because they were viewed by key informants as having knowledge of the daily lives of women with mental illness. Fifty-five case managers were randomly recruited from department of mental health sites across Massachusetts for five focus groups. The criterion for recruitment was that the case managers were currently working with or had worked with female clients with children. Case managers who participated in the focus groups were not necessarily those who provided case management services to the women in the mothers' focus groups.

Focus-group procedures

Five of the six mothers' focus groups were held in the convenient, nonthreatening setting of a psychosocial rehabilitation clubhouse (19,23). One group, with participants from a wider geographic area, was conducted in a centrally located office of the department of mental health. Each focus group met one time for two to three hours. The average number of mothers in each group was seven, with a range from three to ten.

The five case managers' focus groups met in department of mental health case management sites. The average number of case managers in each focus group was 11, with a range from six to 14.

Forty key informant interviews with consumers, researchers, service providers, and policy makers were conducted before the study to ensure that procedures were sensitive to the needs and concerns of participants. A pilot group of mothers provided the opportunity for coleaders and research assistants to evaluate and revise questionnaires, instructions, and group procedures.

The coleaders identified themselves as independent researchers who were not affiliated with services the mothers were receiving. A research assistant was available to each mother to assist with reading and explaining the materials about informed consent and the questionnaires. Because the topic to be discussed in the focus groups was emotion laden, a research assistant was present at each group in case any mothers required individual attention or needed to leave the group. Refreshments were available, and participants were encouraged to move around the room freely.

Experience with the pilot group of mothers led us to pose two general questions to group participants about problems and solutions, rather than use the more structured series of questions originally planned (23). Participants were encouraged to brainstorm a list of experiences, issues, and recommendations. Group coleaders queried the participants about specific topics of interest derived from the literature or suggested by participants in other focus groups. Responses were listed on a poster board.

The focus groups were audiotaped. Focus-group coleaders and research assistants met after each session to record their observations and immediate impressions of the groups. Audiotapes were transcribed by a research assistant, who deleted any information that identified the speaker. A group coleader compared the transcripts to the audiotapes for accuracy.

A Note About This Special Issue

This month's issue highlights articles that share a focus on women and chronic mental illness while addressing a wide range of treatment concerns. Two papers on mothers with mental illness, by Joanne Nicholson, Ph.D., and her colleagues, start the main section of the journal on page 635. They are followed by papers on the parenting capability of mentally ill mothers ho have killed by Teresa Jacobsen, Ph.D., and Laura J. Miller, M.D. (page 650); posttraumatic stress disorder among women veterans by Alan Fontana, Ph.D., and Robert Rosenheck, M.D. (page 658); women veteran with alcohol dependence, by Robin Ross, M.D, and her associates (page 663); dialectal behavior therapy for women with borderline personality disorder in a partial hospital program, by Elizabeth B. Simpson, M.D., and her colleagues (page 669); and a service for women with schizophrenia, by Mary V. Seeman, M.D., and Robin Cohen, B.Sc. (page 674).

Elsewhere, The Taking column, by Sally Satel, M.D., challenges the idea that women's mental health needs should be designated as "special" (page 565). In the Personal Accounts column, Catherine Pemberton, B.A., who has suffered from manic-depressive illness, suggests ho recovery can be supported by responsible utilization review (see page 613).

A brief report on preventive health care for mentally ill women by Jeanne L. Steiner, D.O., and her colleagues begins on page 696. In addition, the books section, begginning on page 701,features reviews of several books focused on women and mental illness, including three books by daughters about their mentally ill mothers.

Analysis of qualitative data

The researchers coded brainstormed items generated in each of the 11 focus groups according to themes suggested in the literature. Additional coding categories were developed as issues were identified by participants. A total of 466 items were identified by the six groups of mothers, and 572 items were identified by the five groups of case managers. Interrater reliability of more than 90 percent was achieved by the three researchers who independently coded randomly selected items from each focus group at several points during the coding process.

The data presented here were drawn from four thematic categories: the stigma of mental illness, day-to-day parenting, managing mental illness, and custody of and contact with children. Patterns among data in these thematic categories were examined to identify sources of conflict for mothers who are balancing the demands of parenting with the challenges of living with mental illness.

Results

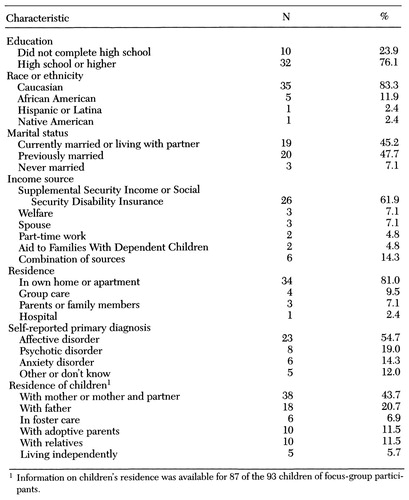

Characteristics of focus-group participants

Characteristics of mothers are summarized in Table 1. Their mean±SD age was 35±6 years, with a range from 22 to 48 years. Thirty-two of the 42 mothers had at least a high school education. The majority were Caucasian, and almost half were currently married. Most derived financial support from Social Security benefits, such as Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance. Thirty-four lived in their own homes or apartments.

The majority of mothers indicated that their diagnoses were in the category of affective disorders, such as major depression or bipolar disorder. The 42 mothers reported a total of 93 children, an average of 2.2 children per family. Thirty-eight children lived with their mothers, or with their mothers and mothers' partners.

Of the 55 case managers who participated in the focus groups, 42, or 76.4 percent, were college educated. Thirty, or 54.5 percent, had some graduate education, and 19 had graduate degrees. Thirty-four, or 62 percent, had been case managers with the department of mental health for five years or less. The average caseload size for these case managers was 25 clients.

More than 80 percent of the case managers had provided services to clients who were mothers caring for their children. The remaining case managers had worked with mothers who were not providing care for children at the time they received services. Thirteen case managers, or 24 percent, had filed child abuse and neglect reports about their clients with the Massachusetts Department of Social Services; three had filed reports four or more times.

Patterns in thematic categories

Stigma of mental illness.

Women with mental illness are the victims of stigma and societal attitudes even before they become pregnant. The normal desire to bear and raise children is undermined by negative societal attitudes, perceived by both mothers and case managers. One mother said, "I guess I feel that if I got pregnant, my child would be taken away from me because I have a mental illness. I feel like I'm sterilized by the department of social services and have no rights." A case manager said, "It is always the stigma of being mentally ill. When they [mothers] go to the hospital to give birth, people immediately assume they cannot care for the child."

Mothers with mental illness feel the additional stress of having to prove themselves. This source of stress motivates some and discourages others. "I think sometimes we make the better parents because it is so hard to be like this and we have to try twice as hard," said one mother. A case manager said, "From the outset our clients have to prove they're able to parent, unlike everybody else who is able to assume they can parent until they prove otherwise."

Given the stigma and stereotypes accompanying mental illness, people may be quick to hold mothers' mental illnesses responsible for children's problems. A case manager pointed out, "Even if it's normal adolescent behavior, they [the mothers] worry that [the behavior] will be viewed as their fault." The assumption may be made that mothers with mental illness abuse their children. A mother said, "We have a mental illness, and people consider that we're going to abuse our children. We're going to take it out on them."

Day-to-day stresses of parenting.

Mothers have to accomplish all the routine tasks of parenting as well as manage their illness. "You have to go to work. You have to come home. You have to deal with the kids, deal with your own home. Your own problems, you know, really start piling up," said one mother. Another said, "It's a seven-day-a-week schedule, you know, with your son and your son's father and yourself. Keeping the entire home organized, keeping things moving smoothly, and then having to deal with all of these different organizations."

Mothers confront role-strain issues, accompanied by stress and guilt. "I think it's hard to have a balance, you know, with the kids and everything else, like the housework," said one mother. Another said, "I need to get out, you know, but in the back of my mind I feel guilty that I need time alone."

Mothers may have difficulty knowing whether they are dealing with the "normal" stress of caring for children or with the symptoms of their illness. One case manager mentioned "the additional stressors of hearing voices [besides] the kids running around. `Which one is that? My kids? Or is that one of the ones in my head?'" Another case manager said, "One of my clients is not always aware of her symptoms of her illness, or [whether she's] just reacting to her everyday stresses of having five children and trying to get them to their therapy appointments, their camp, their this, their that."

In struggling to meet these dual challenges, mothers may lose sight of the typical problems parents have and evaluate themselves against unrealistic standards. One case manager said that clients may say "`The kids are home for vacation. I'm ready to pull my hair out,' and they're so afraid that's not normal. And I'd try to say, `I can remember when the school bus used to pull up to the front door and I wanted to run out of the back.' Everybody feels like that sometimes."

Mothers may blame themselves for problems their children have or misinterpret the normal problems of childhood and adolescence as related to mental illness. One case manager said that a client "looks at her daughter's behavior sometimes and wonders if she is getting sick, too. Or [she may think], `What have I done wrong? Because I have a mental illness, have I raised her wrong?'"

Mothers with mental illness vary in parenting ability. A case manager said, "Some of the very mentally ill mothers that we have have good parenting skills." Another said, "I think sometimes they [the mothers] do understand, maybe, the needs of their kids, but they're not up to whatever it takes to provide that."

They may have difficulty managing children's behavior and dealing with the frustration they feel when their efforts fall short. One mother said, "I can't get my daughter to listen to me." A case manager said, "She [the mother] has a really hard time with a two-year-old. She just flies off the handle a lot easier because of the illness."

Children's special needs may be challenging to mothers. "[My daughter] had attention deficit disorder behavior problems, and I felt like physically I couldn't run after her because she was so overactive," said one mother. Another said, "Without transportation, if you have children with disabilities you have to go here, there, and everywhere. It's very hard—that's enough to make you depressed."

Managing mental illness.

The needs of mothers with mental illness may conflict with those of their children. Mothers may place priority on their children's needs and put their own needs last. They may choose not to take medication or refuse to go to the hospital, compromising their own long-term well-being to meet their children's short-term needs. One mother said, "No medication is going to slow me down. I have a two-and-a-half-year-old daughter. I have to be active for that reason. I have to be right behind her everywhere she goes." A case manager said, "I've seen a lot of mothers go into crisis, needing hospitalizations and debating which should come first, their mental health or child care, because they had no one in the community that could help them."

Mothers with mental illness acknowledge that children may contribute to stress or serve as motivation to recover. Mothers may be willing to get help for themselves if they are convinced this action will help their children, too. "If you're feeling not too good yourself, it seems like the kids, they sense it. And then they act out more," said one mother. "If you can't take care of yourself, you're definitely not going to be able to take care of somebody else, and the first thing you have to do is take care of yourself," said another mother.

Custody of and contact with children.

Mothers with mental illness may fear losing children through voluntary placements when they are hospitalized; through the involuntary removal of children when abuse or neglect is assumed, suspected, or documented; or as a consequence of divorce. Mothers may struggle to maintain relationships with children who are living with relatives or foster parents, with whom visits are sporadic or limited.

One mother said, "When you're not with them a lot, they don't see you on a regular basis, and you can't show them your love in the normal ways that mothers show their love." A case manager said, "I have two mothers who have younger children who are very clear that they can't be the day-to-day custodian, but they really, you know, continually fight around maintaining some involvement and some decision making and some say in the child's life."

A mother's recovery may be compromised if she is not permitted contact with or provided information about her children. One mother said, "My attention was diverted. I could not put my whole heart into my therapy and doing all the things that I had to do because I was so worried about my kids."

Worry about potential loss may contribute to a mother's decompensation. Even when children are returned to their care, mothers may worry they will be removed again. "I think I would die if my daughter was ever taken away from me, especially for the wrong reasons—you know, incompetence," said one mother.

The termination of parental rights may have lifelong effects. One mother described these effects by saying, "My heart is in chains. It never gets easy, not for any mother; that pain never completely goes away." A case manager said, "I have several women whose children were taken away from them anywhere from ten to 20 years ago, and they're still dealing with that loss and probably will for the rest of their lives."

Discussion

The usefulness of focus groups

Mothers with mental illness and case managers provided a great deal of information about the range of mothers' experiences. In contrast to Sands' finding (5) that women minimized the impact of their illnesses on themselves and their children, focus-group participants were quite open in talking about their difficulties and needs. This openness may be the consequence of peer support in the groups and the mothers' providing each other with ideas they may not have offered spontaneously in individual interviews.

Because the women in Sands' study were interviewed in the child care center of their residential program, they may have felt constrained in talking about their parenting deficits and needs. In this study the focus groups were held in neutral space and were conducted by researchers who were not affiliated or not construed as being affiliated in any way with the services the mothers were receiving. These perceptions may have minimized any fear of custody loss that acknowledgment of problems may engender.

The concern expressed by case managers in the recruitment process—that focus-group participation may be too stressful for women dealing with parenting issues—seemed to be unfounded. Only one mother asked to leave a focus group. Several days before the focus group, this mother had suffered a severe trauma that she had not disclosed to her mental health provider or to the researchers, and she became distraught when something said in the focus group reminded her of the event. Every effort should be made to avoid such circumstances in focus-group research.

The vast majority of mothers welcomed the opportunity to talk about their experiences and their children, and they did not want to stop the session at the end of three hours. Their enthusiasm in talking about their children was unmitigated. Many indicated they had never had the opportunity to talk with other mothers who were in the same situation—living with mental illness. Many were disappointed that the focus groups only met one time. In one clubhouse site, mothers continued meeting, opened their group to fathers, and established a family support project.

Case managers expressed similar enthusiasm for the topic. Many struggled daily with the multiple problems of these client families. Some case managers expressed a great deal of concern for the children of mothers with mental illness. Some case managers suggested they themselves were not provided with adequate support for dealing with these issues through normal supervisory channels. Many spoke of the lack of resources for mothers with mental illness. News of the groups spread to case managers in other sites not involved in the project, and they requested training sessions based on the focus-group findings. Case managers have worked to develop new resources in several sites across the state.

How representative were focus-group mothers?

The sample of mothers in the focus groups was largely representative of the population of mothers caring for children under the age of 18 who were enrolled in the client tracking system of the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health at the time of the study. The client tracking system, which is described in more detail elsewhere (24), comprises routine client-level data collected on approximately 8,500 actively case-managed clients across the state.

Focus-group mothers were similar in average age and education level to the mothers enrolled in the client tracking system (35 years of age for the focus-group mothers and 36.2 years for the mothers in the tracking system; 11.8 years of education for the focus-group mothers and 11 years for the mothers in the tracking system). The majority of both focus-group mothers and mothers in the tracking system were Caucasian (84 percent and 73 percent, respectively) and were currently or previously married (93 percent and 70 percent, respectively). More than half of the focus-group mothers and the mothers in the tracking system had diagnoses in the affective disorders category (55 percent and 52 percent, respectively), with smaller percentages in the psychotic disorders category (19 percent and 38 percent, respectively).

Differences between the groups may have been partly due to differences in reporters. Focus-group mothers reported their own demographic information, while mothers in the tracking system were described by case managers. The tracking system considers a client a mother only if she is currently caring for minor children, and it does not identify as mothers all clients who have ever given birth or parented. Case managers who invited mothers to participate in focus groups were asked to correct the department of mental health records to accurately reflect knowledge of female clients' current involvement with children under the age of 13. This process may have resulted in a slightly different, though more accurate, pool of active mothers. It is also important to acknowledge that diagnoses were provided by mothers who participated in the focus group study and by case managers for mothers in the tracking system and were not research diagnoses.

The impact of stigma

The stigma associated with severe mental illness was a pervasive theme for mothers. They were aware that even the idea of their becoming pregnant may be perceived negatively by providers and family members. They understood that their behavior will be constantly monitored and that the incidence of custody loss is great, adding stress that most other parents do not have. A concern voiced by mothers, clinicians, and researchers was that women may deny their pregnancies and fail to seek prenatal care to avoid the stigma and grief associated with anticipated custody loss (6,16,17,25,26,27,28). Women may unnecessarily decide to stop taking medications during pregnancy in an effort to protect their babies, a circumstance that could be avoided if they felt comfortable confiding in mental health or medical providers.

Unfortunately, the stereotype of people with mental illness as violent may contribute to the assumption that mothers with mental illness abuse their children. Because the actual number of parents with mental illness is unknown, it is not possible to determine what percentage of parents with mental illness abuse or neglect their children or how this percentage compares with that in the general population. Some authors have suggested that the percentage of abusive parents with psychotic disorders, for example, is quite low (29).

Normal stresses of parenting

Mothers with mental illness talked at length about what can be considered "normal" stresses for all parents. They discussed the many responsibilities of motherhood and the role strain they felt. Mothers acknowledged that the normal stresses of parenting are exacerbated by illness-related issues. Their routinely busy schedules as mothers were made even more hectic by the demands of appointments with providers and treatment regimes. They sometimes found it difficult even to connect with all necessary services, as has been described elsewhere (30). Mothers were susceptible to viewing their situations and the behaviors of their children through the lens of their illness and may have become myopic in their vision and interpretations. As case managers point out, it is important that mothers are reminded about the range of "normal" parenting experiences.

Mothers, as well as others, worried about the impact of their illness on their children and felt guilty about what they may have "done wrong." Mothers with mental illness wanted information about how to talk with their children about their illness and treatment. This communication is important because mothers' acknowledgment of their illness can help their children cope (14,31).

In this study, mothers reported difficulty managing their children's behavior, both corroborating and extending findings from previous research (5,18). Just as in the general population, mothers with mental illness vary in parenting skill. Illnesses and impairments vary in severity. Some mothers with mental illness have been found to care for and interact with infants normally, even when hospitalized (17). Dealing with children's disabilities may be particularly challenging. Many mothers with mental illness will require specific support for children's special needs.

Illness management

Mothers with mental illness, just like other mothers, may sacrifice their own well-being to meet the perceived needs of their children. This tendency is particularly apparent in situations involving medications and hospitalizations. The women in this study understood that the side effects of medications or overmedication may impair their ability to parent, making them lethargic when they need to have energy or making them unable to "think clearly." Women without resources or plans for child care during hospitalizations may delay obtaining necessary help until a full-blown crisis develops. Mothers may be noncompliant with treatment recommendations or resistant to using services if their ability to parent is jeopardized as a consequence. This seeming noncompliance may work against them when questions of parenting capacity are raised (32).

Women's needs to function as mothers must be considered in treatment planning and the development of illness management strategies. Seeman (33) suggested that therapists support mothers in learning to recognize their own symptoms, seeing them as warning signals, and adopting protective measures to reduce stress. Assisting mothers in developing reliable back-up plans in case of hospitalization is an inexpensive intervention that underscores mothers' strengths. State mental health and social service agencies must develop policies and procedures that are sensitive to the issues of these mothers and their families (34).

Pride derived from parenthood can be a powerful motivating force. Women with mental illness may be motivated to participate actively in recovery efforts by the hope that children will be returned to their care. Focus-group mothers corroborated these ideas, although they acknowledged that children contribute to stress as well as to motivation.

Contact with children and custody loss

Mothers in the study identified their greatest fear as losing custody of or contact with their children. This fear may undermine their well-being and mitigate against service use and treatment compliance. Although the loss of custody does not necessarily mean loss of contact or even caretaking responsibility, mothers described struggling to maintain relationships with children who are living with others. Visitation may, in fact, be painful as mothers are reminded about how things could have been or if they re-experience the pain of separating from their children (3,16). Mothers can be supported in planning for visits and developing ways of staying in touch with children, for example, by making tapes of bedtime stories or preparing calendars with schedules of contacts.

Focus-group mothers indicated that the pain of losing a child, whether through voluntary relinquishment or removal by social services, never goes away. The way these situations are handled by providers and family members can have a tremendous impact on the well-being of women and children (16). Custody loss most likely occurs at varying rates for mothers in different diagnostic groups, with mothers who have psychotic disorders less likely to retain custody than mothers with affective disorders (24,28). These losses, therefore, may have differential effects. Regardless, custody losses must be addressed by clinicians, to help women cope with these situations and to prevent future difficulties associated with unresolved issues of loss.

Conclusions

The perspectives of mothers with mental illness and case managers participating in the focus groups partly corroborated and greatly extended previous research findings and clinical case discussions. Their perspectives elaborated the range of factors contributing to women's parenting careers, their concerns, their struggles, and their successes. Providing an opportunity for mothers to talk together with researchers allowed for the expression of a wider range of experiences and issues than had been attained in previous research. Mothers with mental illness related subtle aspects of their experiences that were previously unrecognized by researchers or clinicians. These findings highlight the essential role mothers must play in developing standards for clinical care in this area and laying out the research agenda.

Many of the issues raised by mothers with mental illness are generic to all parents, others are specific to the situation of living with mental illness. The goals of individual mothers with mental illness, as well as their strengths and stresses, must be incorporated into approaches to assessment and intervention. The balance between the needs of mothers with mental illness and the needs of their children, as well as the conflicts that arise when the demands of parenting and the challenges of living with mental illness compete, must be addressed. And they must be addressed in forums that include, as major participants, mothers with mental illness.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christine A. Baily, M.A. Funding for the study was provided by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health and a public service award from the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Dr. Nicholson is associate professor of psychiatry at the Center for Research on Mental Health Services, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester, Massachusetts 01655 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Sweeney is staff psychologist in the adolescent program in the department of psychiatry, and Dr. Geller is professor of psychiatry and director of public-sector psychiatry at the medical school. This paper is one of several in this issue focused on women and chronic mental illness.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 42 mothers with severe mental illness who participated in focus groups on problems they faced in parenting

1. Gopfert M, Webster J, Seeman MV (eds): Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Distressed Parents and Their Families. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1996Google Scholar

2. Cohler BJ, Stott FM, Musick JS: Distressed parents and their young children: interventions for families at risk, ibidGoogle Scholar

3. Schwab B, Clark RE, Drake RE: An ethnographic note on clients as parents. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 15:95-98, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Nicholson J, Geller JL, Fisher WH, et al: State policies and programs that address the needs of mentally ill mothers in the public sector. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:484-489, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Sands RG: The parenting experience of low-income single women with serious mental disorders. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services, Feb 1995, pp 86-96Google Scholar

6. Miller LJ, Finnerty M: Sexuality, pregnancy, and childrearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 47:502-506, 1996Link, Google Scholar

7. Ritsher JEB, Coursey RD, Farrell EW: A survey on issues in the lives of women with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:1273-1282, 1997Link, Google Scholar

8. Zemencuk J, Rogosch FA, Mowbray CT: The seriously mentally ill woman in the role of parent: characteristics, parenting sensitivity, and needs. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 18:77-92, 1994Google Scholar

9. Poole R: General adult psychiatrists and their patients' children, in Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Distressed Parents and Their Families. Edited by Gopfert M, Webster J, Seeman MV. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1996Google Scholar

10. Silverman MM: Children of psychiatrically ill parents: a prevention perspective. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1257-1265, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

11. Seifer R, Dickstein S: Parental mental illness and infant development, in Handbook of Infant Mental Health. Edited by Zeanah CH. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

12. Seifer R, Sameroff AJ, Dickstein S, et al: Parental psychopathology, multiple contextual risks, and one-year outcomes in children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 25:423-435, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Apfel RJ, Handel MH: Madness and Loss of Motherhood: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Long-Term Mental Illness. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

14. Nicholson J, Blanch A: Rehabilitation for parenting roles in the seriously mentally ill. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 18:109-119, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Oyserman D, Mowbray CT, Zemencuk JK: Resources and supports for mothers with severe mental illness. Health and Social Work 19:132-142, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Nicholson J, Geller JL, Fisher WH: "Sylvia Frumkin" has a baby: a case study for policymakers. Psychiatric Services 47:497-501, 1996Link, Google Scholar

17. Mowbray CT, Oyserman D, Zemencuk JK, et al: Motherhood for women with serious mental illness: pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:21-38, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Mowbray CT, Oyserman D, Ross S: Parenting and the significance of children for women with a serious mental illness. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:189-200, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Morgan DL: Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1988Google Scholar

20. Marshall D, Rossman G: Designing Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1989Google Scholar

21. Glaser B, Strauss A: The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York, Aldine, 1967Google Scholar

22. Campbell J, Schraiber R: The Well-Being Project: Mental Health Clients Speak for Themselves. Sacramento, California Department of Health, 1989Google Scholar

23. Krueger RA: Quality control in focus group research, in Successful Focus Groups. Edited by Morgan DL. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1993Google Scholar

24. White CL, Nicholson J, Fisher WH, et al: Mothers with severe mental illness caring for children. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:398-403, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Miller LJ: Psychotic denial of pregnancy: phenomenology and clinical management. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1233-1237, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

26. Miller LJ: Comprehensive care of pregnant mentally ill women. Journal of Mental Health Administration 19:170-177, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Nicholson J: Services for parents with mental illness and their families. Journal of the California Alliance for the Mentally Ill 7:66-68, 1996Google Scholar

28. Miller LJ: Sexuality, reproduction, and family planning in women with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:623-635, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al (eds): Psychological Evaluation for the Courts. New York, Guilford, 1987Google Scholar

30. Gopfert M, Webster J, Pollard J, et al: The assessment and prediction of parenting capacity: a community-oriented approach, in Parental Psychiatric Disorders: Distressed Parents and Their Families. Edited by Gopfert M, Webster J, Seeman NW. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1996Google Scholar

31. Judge KA: Serving children, siblings, and spouses: understanding the needs of other family members, in Helping Families Cope With Mental Illness. Edited by Lefley HP, Wasow J. New York, Harwood, 1994Google Scholar

32. Jacobsen T, Miller LJ, Kirkwood KP: Assessing parenting competency in individuals with severe mental illness: a comprehensive service. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:189-199, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Seeman MV: The mother with schizophrenia, in Parental Psychiatric Disorders: Distressed Parents and Their Families. Edited by Gopfert J, Webster J, Seeman MV. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1996Google Scholar

34. Blanch A, Nicholson J, Purcell J: Parents with severe mental illness and their children: the need for human services integration. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:388-396, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar